In the days following the release of The Tree of Forgiveness, John Prine — the 71-year-old master song crafter, storyteller, and lover of a good meatloaf — had the best sales week of his decades-long career. His first album of originals since 2005’s Fair and Square, it’s a rare bit of triumph for the good guys — and for an artist like Prine, who has shaped our current musical climate in ways that are often beyond measure. Because, despite being one of the primary influences on Americana’s best and brightest — from Jason Isbell to Margo Price and Deer Tick — Prine’s never banked those platinum albums. Though 1991’s The Missing Years eventually sold around a half-million copies some 20 years after his self-titled debut, records, like the rest of human life, then went online: People stopped buying, and started streaming.

“Just as I started selling records, records stopped selling. I hope it wasn’t my fault,” Prine says, chuckling from his living room at home in Nashville. “I’d be spoiled, if I sold a million records. I probably wouldn’t go on the road for 10 years. But I don’t ever want to sell so many records that I have to do shows in a stadium. Stadiums are for sporting events: They’re not to watch a guy with a guitar come out and tell his story.”

He’s right, though if there’s anyone who could capture a stadium full of people with just an acoustic guitar and his heart-shaking stories, it would be Prine. The Tree of Forgiveness, an exquisite record that finds Prine looking at love, death, and the passage of time with humor, lightness, and his own quirky sort of grace, isn’t a set of arena rock barnburners (obviously). Instead, it’s touching moments of humanity that stick to the bones and linger in the mind, letting the imagination wander in exactly the direction that Prine wants it to … which is everywhere. Take “Summer’s End,” a nostalgic track if there ever was one, though it’s not explicitly clear for what — for summer, for a relationship, for life itself. “I could sell John Prine Kleenex with a song like that,” he says, laughing.

But it’s hard to be too sad about the end of life or love in Prine’s world, particularly life, if what happens next is as fun as “When I Get to Heaven,” the album’s closer. With Amanda Shires, Jason Isbell, and Brandi Carlile all chiming in on kazoo and vocals — all three appear across the Dave Cobb-produced LP — it details Prine’s perfect afterlife, where he can smoke again, post-cancer, hug his loved ones, and drink his signature cocktail, the Handsome Johnny, to his heart’s content. Like most of what Prine does, “When I Get to Heaven” is loaded with a potent combination of humor and vulnerability. Death is life’s biggest mystery, and Prine would rather solve that problem with lightness than exist in the dark, reality be damned. And Prine likes a good story as much as he likes (or doesn’t like) reality, anyway.

Prine’s own life story is a bit of rock ‘n’ roll lore: He grew up outside of Chicago in a mill town, and formed his songwriting voice after leaving the Army, writing between shifts as a mailman. But much of his signature finger-picking style and his artistic identity come from Kentucky, where his father hailed from, and which feeds the deep bluegrass presence within his songs.

Prine is equally important to Kentucky, too — and to Kentucky’s artists, like Kelsey Waldon, who will open select shows for him in the fall. “John Prine’s music is very special and significant to me,” says Waldon. “He brought together my country and bluegrass worlds, but with relevant and honest songwriting that I think would touch most any walk of life. As a Kentuckian, yes, of course his bluegrass roots make me proud. I have spent some time in Muhlenberg County, and I believe that’s where John learned to play, from his grandfather. That is the area where the great Merle Travis is from, and you can really hear a lot of Merle in John’s pickin’ style — that rhythmic thumb picking. The Everly Brothers and Bill Monroe are also from around the same area so, you know, it’s a lush environment for music. Something has always been in the water. I had heard in an interview that his daddy used to drill the kids that they were not only from Illinois, but also from Kentucky. So, I’d say the roots run deep.”

“I can never really lose those roots,” Prine says. “My family is a big part of my life. A lot of the older relatives are gone now, but I still have family in Kentucky, and I still go to my family reunions every year. Country and bluegrass have always been big influences on me and my music. I still listen to that music.”

Prine listens to a lot of Isbell and Shires, too, and Sturgill Simpson, a fellow Kentucky native with whom he shares a songwriting office — which has never actually been used for any songwriting. Prine stores a big pool table there and, besides, they can’t give it up. Producer/engineer Dave Ferguson uses the space next door, and he likes to smoke there, so Prine and Simpson hold on to it so a new tenant doesn’t put the kibosh on the stogies. “Friendship and cigarettes,” Prine says.

“I would love Sturgill if he was from New York City,” says Prine, “but he is from Kentucky, and I love that he respects and cherishes those roots as I do. He and I both come from the same long line of country-folk-bluegrass guitar-playing musicians. I learned to fingerpick by listening to Elizabeth Cotton and musicians in our tradition. We are all still playing and writing about stuff we know.”

One of the reasons that Prine’s songs are so impactful is how they balance what he knows and what he doesn’t — the mysteries of life, its frustrations, and unknowns. On The Tree of Forgiveness, recorded at RCA Studio A, he’s thinking a lot about forgiveness, itself, and what it means to be kind, something that resonates loud and clear in the Trump era. Prine didn’t write explicitly political songs on this record, but that simple act of forgiveness and kindness is political, in and of itself, in 2018 — a concept that other country and folk singers, like Kacey Musgraves and Courtney Marie Andrews, have also explored on their recent albums.

“Forgiveness, to me, it’s probably the most difficult thing to do,” Prine says. “And the most difficult person to forgive is yourself. A lot of people go through life not forgiving themselves for short-selling something, or paying enough attention to kids or parents, not looking after them when they get old. But the most difficult thing is to forgive yourself.”

Prine’s songs include so much permission to forgive ourselves for being imperfect, for acknowledging that we can love our weaknesses as much as our strengths, and for being content with our priorities, however skewed they may be. Some of Prine’s personal priorities are songs, a good meatloaf, and friends and family. His record label, Oh Boy, is a family affair, with his wife and manager Fiona running things with their son, Jody Whelan. When he’s not touring or playing with his grandkids, he’s writing with friends like Dan Auerbach, who appears on the record, and Pat McLaughlin, or seeing shows around town. He recently checked out the I’m With Her gig at the Station Inn in Nashville. “His support is incredibly meaningful,” says Sara Watkins, who could see he him bopping along from the stage.

“The longer I live in Nashville, I only co-write with friends,” says Prine. “Because, if you spend an afternoon together and you don’t write a song, at least you get to hang out.” For one of The Tree of Forgiveness‘s tracks — “Egg & Daughter Nite, Lincoln Nebraska, 1967 (Crazy Bone)” — Prine and McLaughlin were writing together on a Tuesday (“meatloaf day, that’s our carrot on a stick”) and Prine brought up a story about how he’d heard of farmers taking their daughters to town in order to pawn them off for marriage — which he’d heard jokingly referred to as “egg and daughter night.” Naturally, this gave Prine a good laugh. And an idea.

Prine didn’t think it was a real thing, though (according to Google, apparently, it is), but they wrote the song anyway. “We didn’t think it was about the truth and, when you aren’t writing about the truth,” he says, “the world is your oyster.”

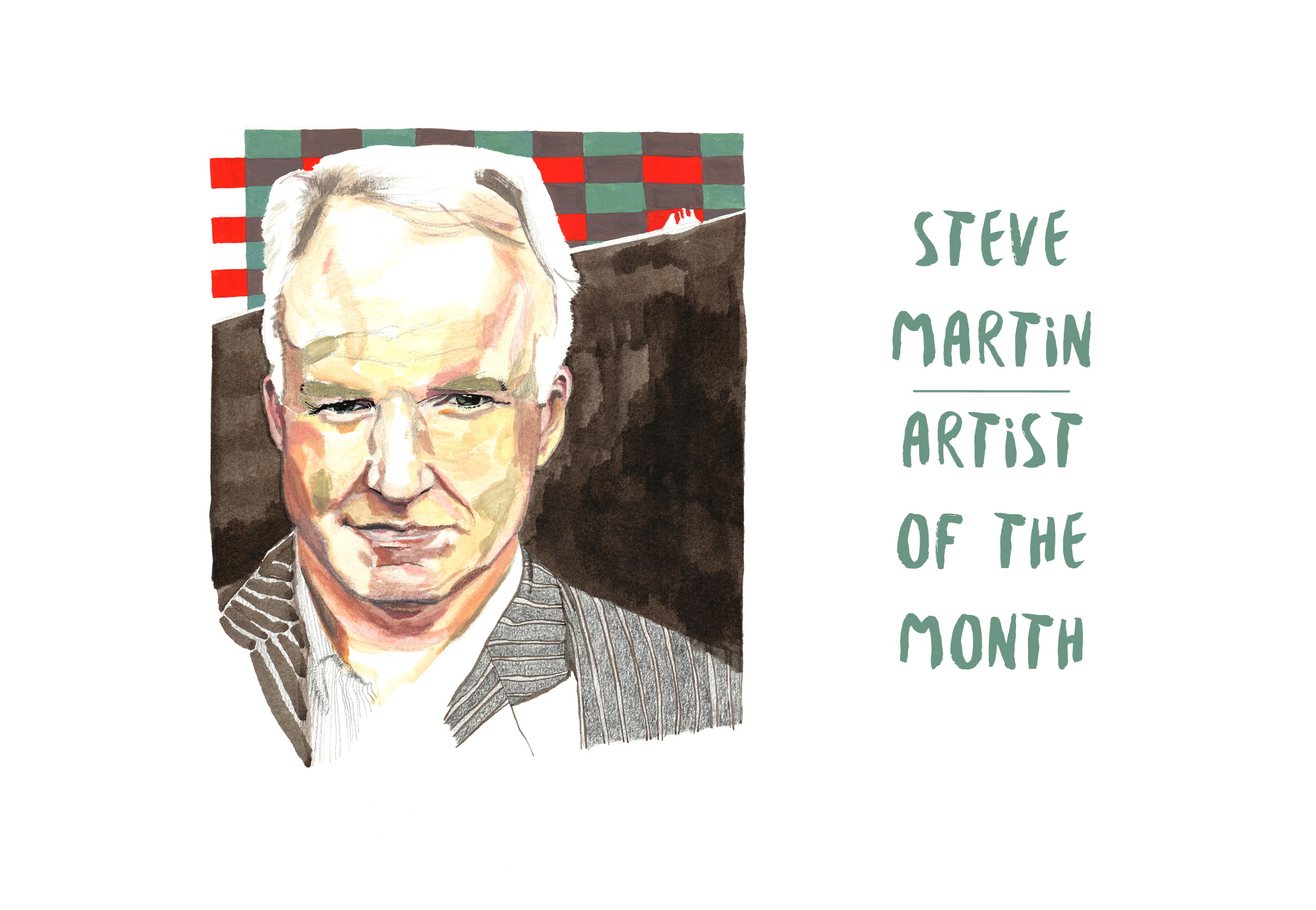

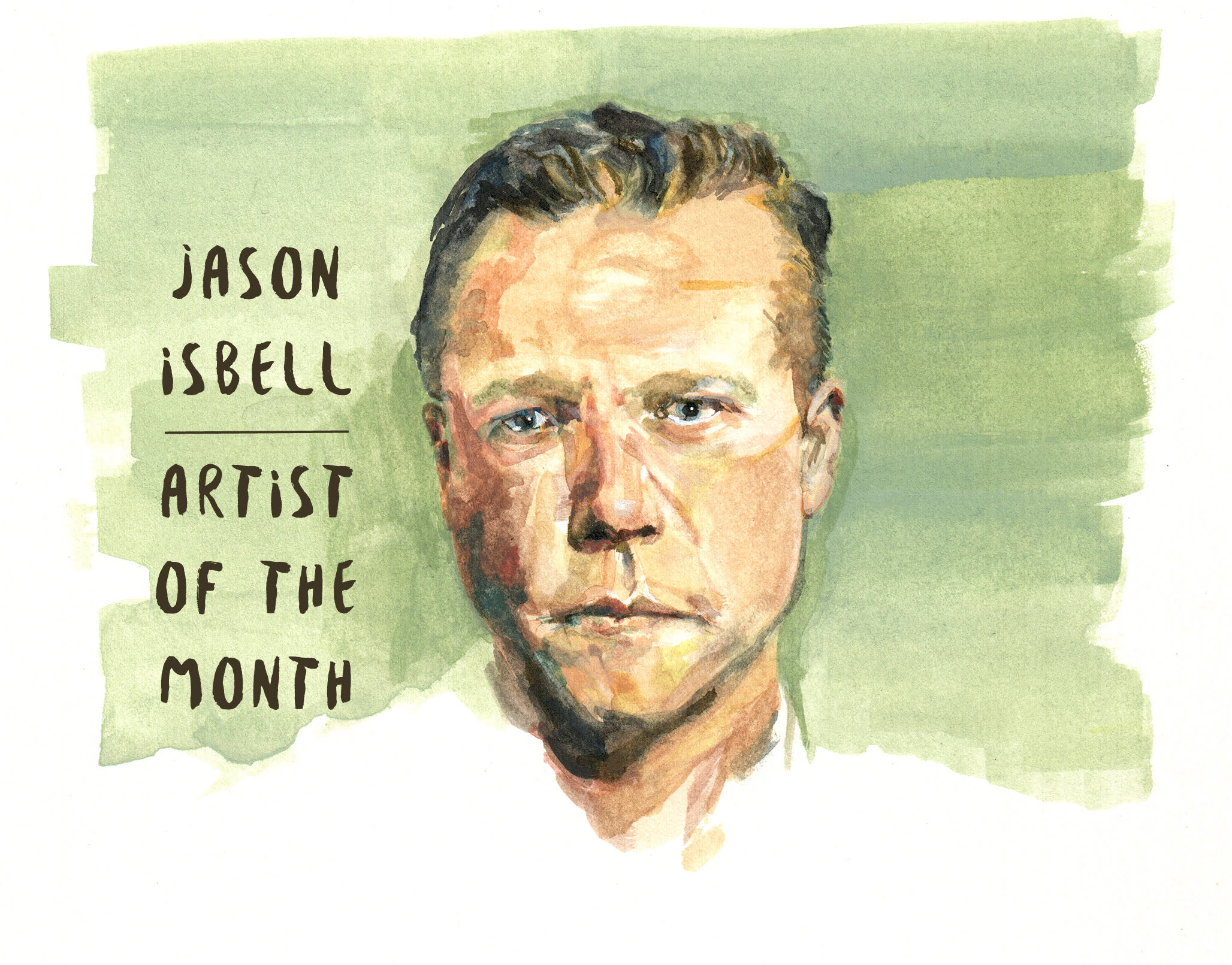

Illustration by Zachary Johnson