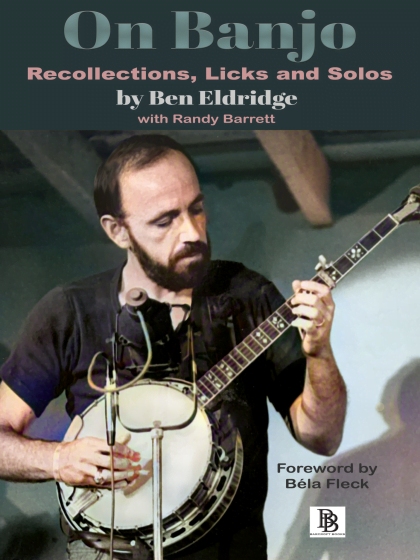

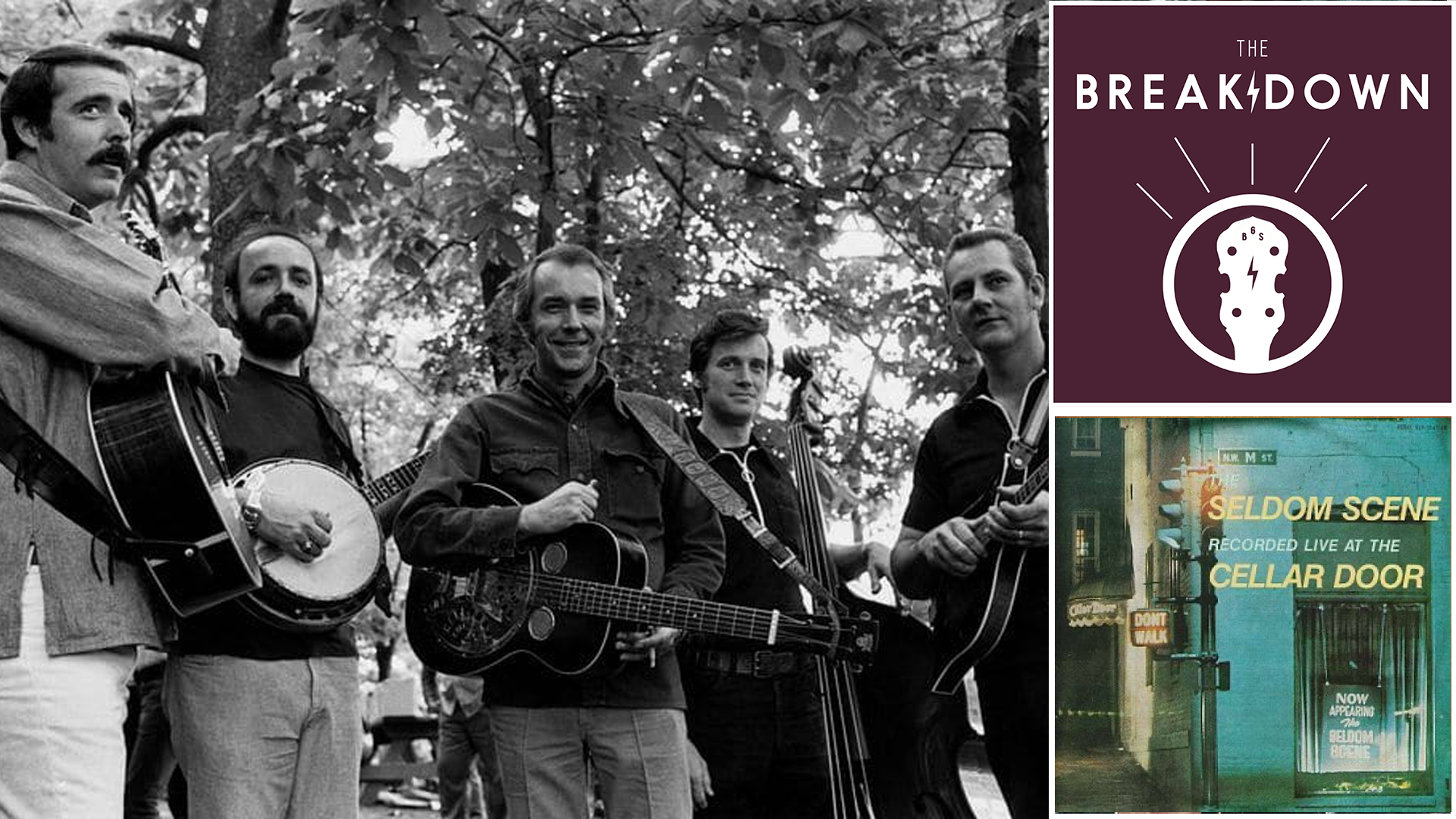

After 53 years and 23 albums, the release of the newest Seldom Scene recording is still something to celebrate. Remains to Be Scene is their first recording since the death of founding banjo player Ben Eldridge in 2024 and the last before Dudley Connell announced his retirement. In addition to Connell, the album features Fred Travers on Dobro, bassist Ronnie Simpkins, mandolinist Lou Reid, and Ron Stewart on fiddle and banjo.

Since its earliest days, the Seldom Scene has been known for busting open once-limiting bluegrass boundaries. The latest album continues this tradition, with songs pulled from sources like The Kinks, Woody Guthrie, and Jim Croce. Another tradition is incorporating new talent.

In 1995, three of five band members left to form another group. Looking to replace them, founding member John Duffey invited Simpkins, Connell, and Travers to a picking session. To those who didn’t know him, Duffey, with his huge stage personality, was intimidating.

Remembering that day, Simpkins said, “I did not want to be late, but I did not want to be early. So, I got there way ahead of time, and I kept an eye on John’s house to see who else got there.

“And I noticed this other car down the street. That person was just sitting there and would ease the car up closer to John’s as the time drew near. And I came to find out it was Dudley. So, we timed it until Ben got there, and we all went in together.”

Simpkins takes Connell’s retirement as a continuation of the band’s legacy: “The band has always transitioned.” Today he welcomes Clay Hess, a band leader and a former lead guitar player with Ricky Skaggs & Kentucky Thunder, who stepped in quickly when Connell, injured in a fall, was unable to play the last few shows of 2024.

As always, the Seldom Scene is committed to the same scalp-tingling vocals, remarkable song selection, and quirky, sometimes outrageous, stage shows that fill festival seats after five decades. Simpkins said, “I just feel blessed to be in this group … and to try to keep the same spirit the original guys had when they started out back in 1971.”

On the release of his last recording as a Seldom Scene member, Dudley Connell spoke to BGS about Remains to Be Scene, his musical career – starting in the 1970s – and his memories of some of the greatest characters in bluegrass.

The Seldom Scene has a tradition of pulling songs from everywhere and the latest recording is the same way. How do you decide on songs?

Dudley Connell: If you look back at the Scene’s recording career, all the way back to the original guys, it was unique. John Duffey had very eclectic taste. He brought “Rider” into the band from the Grateful Dead. He brought “Sweet Baby James” in from James Taylor. And continuing that tradition, I brought in “Boots of Spanish Leather” by Bob Dylan and “Nadine” from Chuck Berry.

It’s interesting having a band of five people, all with slightly different tastes, but with commonality at the same time. So, that’s the way we’ve continued the work all the way through our 30 years together. Everybody would show up with a basketful of songs. Sometimes, Lou might bring a song in that he really liked and say to me, “I could hear you singing this more than me.” Likewise, I could say to Fred, “I really like this song, but I don’t think I could sing it as well as you could sing it.” And it worked that way really well.

How does a band stay together so long?

We, of course, spent a lot of time together, but we also spent a lot of time doing our own thing. Now, with [a band leader] like Bill Monroe or Ralph Stanley, they take the fee and then they give you whatever they want to pay you per show. But with the Scene, John [Duffey’s] feeling was that if you’re out there on the road and you’re doing the work, you deserve equal cut. So, everything we made was split equally. You could fly, you could drive, you could stay at the Waldorf Astoria, or you could stay at the Super Eight. It was your money to spend and to travel as you wanted.

I think it created a certain sense of camaraderie that continues to this day. Everybody’s getting paid the same, so everybody’s expected to do equal work, and it gives you a sense of belonging. There’s no boss, everybody has an equal say, and that was true from the very first rehearsal.

Every group you’ve been with has been known for exceptional harmonies. Can you talk about harmony a bit?

I think a musician’s greatest asset and greatest tool is his or her ears. If you’re singing a trio, you want the blend to be there. You don’t even have to actually know who’s singing what part. There’s a certain buzz you get when the harmony is just right, and you hit a chord just right, and everybody’s phrasing together, and their mouths are in the same sort of position. When that happens, this is just like magic.

Let’s go back to the Johnson Mountain Boy days, when I first met Richard Underwood. Richard learned to sing with me. When we sang together and I switched from lead to tenor on a chorus, you could hardly hear the switch. It came natural to him, because I’m the only person he ever sang with. You know, he later went on to become a great singer on his own right, but he was the first singer that I really worked with a lot on blending and making a pleasing sound.

Now, my experience with David McLaughlin was more organic, as it was with Don Rigsby. Don and David and I all grew up as disciples of the Stanley Brothers. They had such a tight blend.

Now a more challenging partner for me was Hazel Dickens. Hazel and I toured quite a bit together in the ’70s and ’80s. But Hazel had a completely different sort of approach. Hazel was full bore, wide open all the time, and sometimes she could get just a little bit pitchy. I looked at it as my job to try to keep her close to the melody. It was great for me, because it taught me how to blend and also how to pull her to the proper pitch when necessary.

When I came to work with The Scene, it was completely different. They were all about the harmony.

What are your memories of The Scene before you joined them?

The Scene were a huge influence on everybody in D.C. The Scene was almost like a gateway drug to bluegrass music. They were largely playing for urban audiences in the early days, and a lot of young people really responded to it. In fact, The Seldom Scene record Live at the Cellar Door almost has cult-like status. When I was a teenager, we’d go to each other’s houses to listen to music. Right next to Led Zeppelin and Jimi Hendrix and Bob Dylan would be The Seldom Scene Live at the Cellar Door.

I think what made that record so absolutely deserving of cult status is that it’s really freewheeling, it’s really the band live. It’s not just the music and the wonderful singing, the wonderful song selection. It’s also the playfulness with the audience.

As far as I was concerned, John Duffey was The Scene. It wasn’t just that he was a great singer and instrumentalist, but also he had this gift – presenting the music to all kinds of different audiences. You couldn’t not respond to John Duffey or his emcee work – or his pants, for that matter. An interesting thing about John that a lot of people don’t realize is that he was actually kind of shy, kind of insecure. This bigger-than-life character that emerged on stage – I’m not saying that it was phony. It really was John. But when he walked on stage, it was like a switch kicked on, and he became a great entertainer and a great communicator.

I think people who weren’t familiar with bluegrass, it put them at ease a little bit. It drew a lot of people in who maybe wouldn’t have paid attention to a banjo or a Dobro. All entertainers feed off audiences. If you’ve got a really lively, energetic audience, you pour a lot of that back. If the audience feels more relaxed, you slow down a little bit with your delivery and your introductions. And John was an absolute master of that. I learned a lot about presenting a show from my year with John.

And how did you come to play with The Scene?

The Johnson Mountain Boys were on their way out. I’d done a little bit of work with Longview by this time. Then I got this notice in the mail that T. Michael Coleman, Mike Auldridge, and Moondi Kline were leaving the Scene and forming a band called Chesapeake. And it was sort of assumed that the Scene were going to dissolve. I knew John well enough and I called him on the phone and said, “John, I’m really sorry to hear about this. It sounds like the end of an era.”

And he said in the off-the-cuff, John Duffey style of talk, “Well, we’re really not dissolving the band. We’re just looking for a lead singer, guitar player, tenor singer, bass player, baritone singer, Dobro player.” You know, basically replacing three-fifths of the band. I don’t know where it came from, because I really had not called John looking for a job, but after he told me what he was looking for, I said, “Well, John, let’s get together and sing sometime.” Complete silence.

After the initial silence, he said, “Well, do you know of any of our stuff?”

So, I went over to John’s, and Ronnie was there, and Fred. John had given me about half a dozen songs to learn and when I look back at it now, he was testing me. He wanted to see if I could sing harmony parts over and under him. By that time, I’d had the experience with Hazel and had sung with a lot of different people. I was ready.

So, we started these Wednesday rehearsals and we’d done this for about two or three months in preparation for our debut – New Year’s Eve at The Birchmere, 1995. By the time it actually came to play our first show. I was really, really into it. And it was one of the toughest shows I think I ever played, because all the original guys were there – John Starling, Mike Auldridge, Tom Gray. Lou Reid was there, too. And I’m thinking, “I don’t know, man. I don’t know if I belong in this – with these people that I’ve listened to for years.”

One of the things I remember was our opening song, “Our Last Goodbye,” which is this old Stanley Brothers song. I had worn these baggy chino kind of pants and I was so grateful that I didn’t wear tight pants because my legs were literally shaking, and I didn’t want anybody to see that.

So, it was a very exciting night, and after that we had a year with John.

You were quite young when you formed the Johnson Mountain Boys. Can you tell us about those years?

I came along at a very fortunate time in the Washington, D.C. area in the ’70s, and actually on through the ’80s as well. You could see bluegrass every night of the week between Washington and Baltimore.

Now, I’m not going to tell you that the places were swank and nice. They were kind of seedy bars. But when I look back on it now I think that was actually a very beneficial thing for us. We were young, we were very enthusiastic about the music, and we could go into these bars and play four or five sets ’til, you know, one or two in the morning … and then go play another one the next night. So, by the time that the ’80s rolled around and we started actually playing festivals for larger crowds, we were pretty well rehearsed.

I found that the musicians that we met, like Del McCoury and Bill Harrell and a lot of the acts around Washington, embraced us because we were doing something different – actually doing something [traditional bluegrass] that had been done before, but we were kids doing it.

Ben Eldridge– the first time I ever met him, we were playing this indoor bluegrass event. Ben came over and said, “I wish I was doing what you guys are doing.” I know that he was kidding me, but the point being that he really respected the traditional stuff. He said it because he was very sweet man and very kind man. But I think there was some truth in that, too.

How much time was there between you playing in the two bands?

We actually intertwined for just a little bit. When we got off the road full-time in 1988, we were kind of burned out. I went back to college. David [McLaughlin] started selling real estate. Eddie [Stubbs] went to work with his father and we just sort of drifted apart, personally and musically.

Now, we did get together and play some in the ’90s and we produced a record that was nominated for a GRAMMY, Blue Diamond. But that was not like the previous Johnson Mountain Boy records. So, The Seldom Scene coming along at that time in my life, when I was curious about experimenting with different kinds of music, was perfect.

They played a lot locally and I was working full-time for the Smithsonian and didn’t want to travel very much. And the Scene, to this day, has followed that model. We don’t get on the tour bus and go out for weeks at a time. It reminds me of the reason John Duffey left the Country Gentleman. He said he got tired of saving up to go on tour. I understand what he meant. They were just going out trying to get their name out there. The Johnson Mountain Boys did the same thing. I remember once we drove to Florida to play for 900 bucks for three days.

That’s another thing that John did, he just set the price to where it made it worth his while to go. Here’s a kind of famous John Duffey story: A promoter in California called John and said, “I really, really like what you’re doing, and I’d like to get you out here to California.” John said, “Great! Make me an offer.” The promoter said, “Will 500 bucks do it?”

John thought for a minute and said, “Which one of us do you want?”

I’d like to talk a bit about your career as an archivist. Did you go to school to learn that?

Actually, I didn’t. After the Johnson Mountain Boys got off the road, I went back to college. One of my classes was Career Development. There were a lot of people around my age who were looking for a change in their work and their livelihoods.

One of my assignments was to interview someone that I thought had a really interesting job. So, I chose to interview the curator and the director of Smithsonian Folkways records. His name was Tony Seeger, and yes, he is a part of the Mike and Pete Seeger world. The Smithsonian had just acquired Folkways Records. I went into the interview asking Tony how he got his job, what his educational background was, how he ended up at Smithsonian Folkways, what his life was like. About halfway through the interview, he started asking me about my background and what I’ve been doing.

Before I left his office, he basically hired me to come in and try to figure out how to how to keep Folkways alive.

And then you did archive work for another organization?

It’s called the National Council for the Traditional Arts. Since 1933 they have put on folk festivals with all kinds of ethnic and roots music. They started recording all the festivals in 1972. When I got there, they were just quite a thing of beauty – 5,000 hours of one-of-a-kind recordings in a non-climate-controlled room. So, I went to work there, preserving the recordings. And oddly enough, the very first that I put up to digitize was Alison Krauss. I thought, “I think I found the right place.” I worked there for 19 years.

Why retire now, and what’s next?

My wife, Sally, had retired from 40 years at the Smithsonian’s Natural History Museum. I had retired from the National Council for Traditional Arts. This would have been the end of 2023, so I was still traveling on the weekends.

During the pandemic, we got a dog named Woody. It’s almost like having a child in the house. He was adopted and he was afraid of everything, so we spent a lot of time with him. Before that, Sally used to travel with me everywhere and it got to be that she had to stay home and take care of the dog when I was out on the road. I wanted to have time to travel, to Europe and to different places that I’d not really been able to explore. I think it’s a misconception some people have about a traveling musician: “Wow, you got to go to all these great, cool places. You must have seen a lot.”

Well, I saw a lot of hotel rooms. I saw a lot of backstages, but I didn’t see some of the things these towns are known for. What Sally and I want to do now is, while we’re in reasonably good health and while we can still get around well on our feet, we want to do some traveling and not be restricted by a schedule.

Favorite memories?

Marrying Sally, definitely a favorite memory. In the ’80s, an organization called the United States Information Agency USA had a subgroup called Arts America. They created cultural exchanges with third world countries. I got to travel to Southern Africa and later Southeast Asia. You can’t buy that kind of education. It’s quite an eye opening event. I remember coming back from those trips and having a different way of looking at my lifestyle and where I live and how fortunate we are.

Another highlight was getting to meet my heroes and finding out that they were really nice people who didn’t want anything more than to see me and our bands, whether it be the Seldom Scene or the Johnson Mountain Boys, succeed. I never felt any jealousy or any animosity, you know, toward us, these young upstarts. In the ’70s and ’80s, everybody knew everybody, and everybody wanted everybody else to succeed.

But probably the biggest thing was having a year with John Duffey and many years with Ben Eldridge; hearing their stories, the hardships, and the fun stuff and the silliness that happens on the road. All those things are highlights for me.

Closing thoughts?

The music of the Scene is completely unique to anything else in the bluegrass world. I think the Scene could follow just about anybody. We followed Alison Krauss and we followed Ricky Skaggs, and I never really felt uptight about our performance following these major acts, because nobody else does what the Scene does. That’s true with Clay Hess taking my place, too. I’ve heard some of their performances on Facebook – sounds like the Seldom Scene to me.

I feel like I’ve lived a very full life. It’s like when Tony Trischka was asked, “Tony, have you been playing banjo all your life?” He answered, “Not yet.”

That’s the way I feel about music – I’m not done yet.

Photo Credit: Jeromie Stephens