Call us lucky that Dale Watson is feeling so lucky these days. He’s recently bought a house in Memphis, the city where he recorded his new album Call Me Lucky at Sam Phillips Recording studio, purchased the famous nightclub Hernando’s Hideaway, and continues to develop his sound and to reign as the king of Ameripolitan music. Call Me Lucky includes traveling tunes, love songs, and trucking songs, all under three minutes, and featuring Watson’s signature rockabilly sound.

On the slow-burning ballad “Johnny and June,” Watson and Celine Lee, who co-wrote the song, channel Cash and Carter as they look into each other’s eyes and sing about how deeply their lives are intertwined: “you’re the cream in my coffee/you’re the grits to my gravy/you’re the wind in my sails/a lullaby to my baby.” Cash’s drummer W.S. “Fluke” Holland provides the driving beat for “The Dumb Song,” which features a galloping bass line straight out of the Man in Black’s catalog. Every track features Watson’s inventive songwriting, from the Waylon Jennings-like “Restless” to the scampering Merle Haggard-esque “You Weren’t Supposed to Feel This Good.”

BGS caught up with Watson by phone for a chat about songwriting and his new album.

BGS: You recorded this album in Memphis at Sam Phillips Recording studio. Why did you decide to record it there?

Watson: Mostly I record my albums here in Austin, either at my studio, but sometimes at Willie’s or at Ray Hubbard’s studio. A friend of mine, Matt Ross-Spang, who’s a great producer, had been working over there and I went to visit him. I became close to the Phillips family. Since the 1960s, some of the greatest American records have been made there. It felt like home, and it has this great sound, of course.

What made you decide to buy a house in Memphis?

I’ve always liked Memphis. Wherever I was going that took me in that direction, I’d stop in there. The city has grown but it’s done well in cleaning itself up. Memphis reminds me of Austin in the ‘80s. I can record where I want but I wanted to come here to do this one.

You recently purchased the fabled Hernando’s Hideaway nightclub. Is it open yet? How does owning a club help you in your own music?

We’re still doing work on the club but hope it will open up sometime later this year. Hernando’s Hideaway is the only bar where Elvis, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, and Charlie Rich played in, never at the same time, though. I am able to get discs from new bands, so I hear some new music. As the owner of the bar, I have to really look for these people to perform and play the kind of music I want in the bar. If I sit in the bar, though, I am going to hear some music that I really like and that I want to hear more of.

Is this album a bookend to your 2015 album Call Me Insane?

(Laughs) I never put those two things together. I never thought of that. The label wanted to go with one of songs for the title, and this is what they chose.

Who would you say are your major influences?

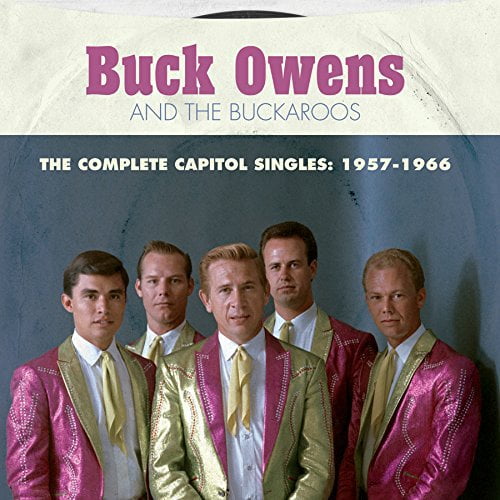

Merle Haggard, Ray Price, Buck Owens, Lefty Frizzell, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins.

Can you define Ameripolitan? How did you come up with the term?

I came up with the term out of frustration, I think. (laughs) I’d be somewhere, and people would ask me what kind of music I do, and I’d say country music. They’d say, “I love Kenny Chesney.” Nothing against them, but by today’s standard of country music, they’d be disappointed with my music. If I tell them my music sounds like Hank Williams or Jimmie Rodgers or Merle Haggard, more often than not people say they’ve never heard of that.

So, it’s easier to explain what we are by using a different word, Ameripolitan, to describe original music with a prominent roots influence. It starts with Jimmie Rodgers and has a relationship to music between Rodgers and Hank Williams. We’ve been holding the Ameripolitan Awards Show now for six years and promoting the music. We held the first four shows in Austin; this year’s show we held in Memphis.

You have a knack for writing songs quickly. What’s your view of songwriting? When did you start writing songs and playing guitar?

Early on, I learned to write from my dad, who wrote songs. When I was about seven or eight years old, I started making up songs on a ukulele. A little later I wrote a song about the girl across the street. All the good ones are about the girls. (laughs) I’m not writing “American Pie.” I pick a subject or I write about people or a situation I see. You write and you write and you have an album.

I was cleaning up my place for a move a couple of years ago and I found a good song that we dusted off. The only time I wrote songs on the way to the studio to go on an album was for the Sun Sessions. I wrote about four to five songs on the way there. I started playing guitar when my brother Jim needed a rhythm guitar player in his band. He taught me how to play some chord progressions. Two years later I had my own band and I learned on the job.

You wrote “Inside View” on the spot in a club. How did you come up with it?

We were playing the Continental Club in Austin. There were these two girls near the stage and they kept screaming for me to play “inside view, inside view.” Well, we didn’t have a song called that but I said, “All right, ‘Inside View.’” I turned to my band and I wrote the song there on stage. My drummer and road manager, Mike Bernal, usually records our music; he’ll send it to me later to refine. Usually I have to go back and re-record, but I didn’t have to do that with “Inside View.” I get most of my ideas from my audience.

How did the idea for “Johnny and June” come to you?

I was driving with my daughter when the idea came to me, and she wrote it down as I told her about it. I played Johnny’s guitar on that one. It’s got that Cash vibe to it and it’s a duet between Celine and me.

There’s a song on the album called “David Buxkemper.” How did that song come about?

I never met the guy before I wrote the song. One day I got an email through my website from this guy named David Buxkemper. He told me he was a big fan of the Reverend Horton Heat, and he’d seen me on tour with Heat. He told me he was a truckin’ farmer, and he was a big fan of my trucking songs. He also told me he and his grandfather used to watch Hee Haw together and that he liked listening to trucking songs while he was farming. I was intrigued by his story, and with a name like that—you can’t make that up! So I asked him for more details about his life and ended writing this song about him. I like writing about real people.

Photo credit: Mike Brown