Apart from going all TSwift-style pop crossover, the easiest way to distance oneself from modern commercial country is to make loud and clear references to an old older era of the genre — or to just play it straight throwback style. But at a time when honoring the past has become so fashionable that it may elicit a blasé response from the more cynical of listeners, Sam Morrow remains grounded in the present through a commitment to his own ears and a desire to grow and try new things. He intentionally breaks up and flips sonic variables, but only to a degree that the studied listener will still recognize the presence of bygone innovators such as Gram Parsons, Little Feat, Lynyrd Skynyrd, and Waylon Jennings, while guessing at the precise methods used to achieve those sounds. If the progression of his works to date means anything, and as Morrow continues to put forth new recordings, expect evolution and growth. It wouldn’t be surprising to see both deeper dives into and further departures from his current country funk/Southern rock sound.

Morrow is an artist committed to finding and refining his true voice, but on his newest album, Concrete and Mud, he doesn’t weigh that pursuit down with an agenda or a need to sound too profound. He laughs at his foibles and winks at his vices. Like so many artists before him, when the Los Angeles-based Morrow got clean from an opiate addiction, he had strange emotions to process, so he turned to songwriting in an effort to root out a bevy of conflicting feelings and past wreckage.

2014’s Ephemeral was his first artistic exorcism, expressed in the emotional, sincere style of a Damian Rice or a Justin Vernon. However sincere, Ephemeral doesn’t sound like someone who has quite discovered his authentic voice yet. Despite its title’s indication to the contrary, Morrow’s second album, There Is No Map (2015), sounds more like someone who knows where he’s come from and where he’s going. But his newest work, Concrete and Mud, displays the confidence, mastery, and winsomeness of an artist who knows exactly who he is, what he wants to say, and what he is doing. The set marks the moment Morrow rightfully claims his place among the very best that country and Americana have to offer.

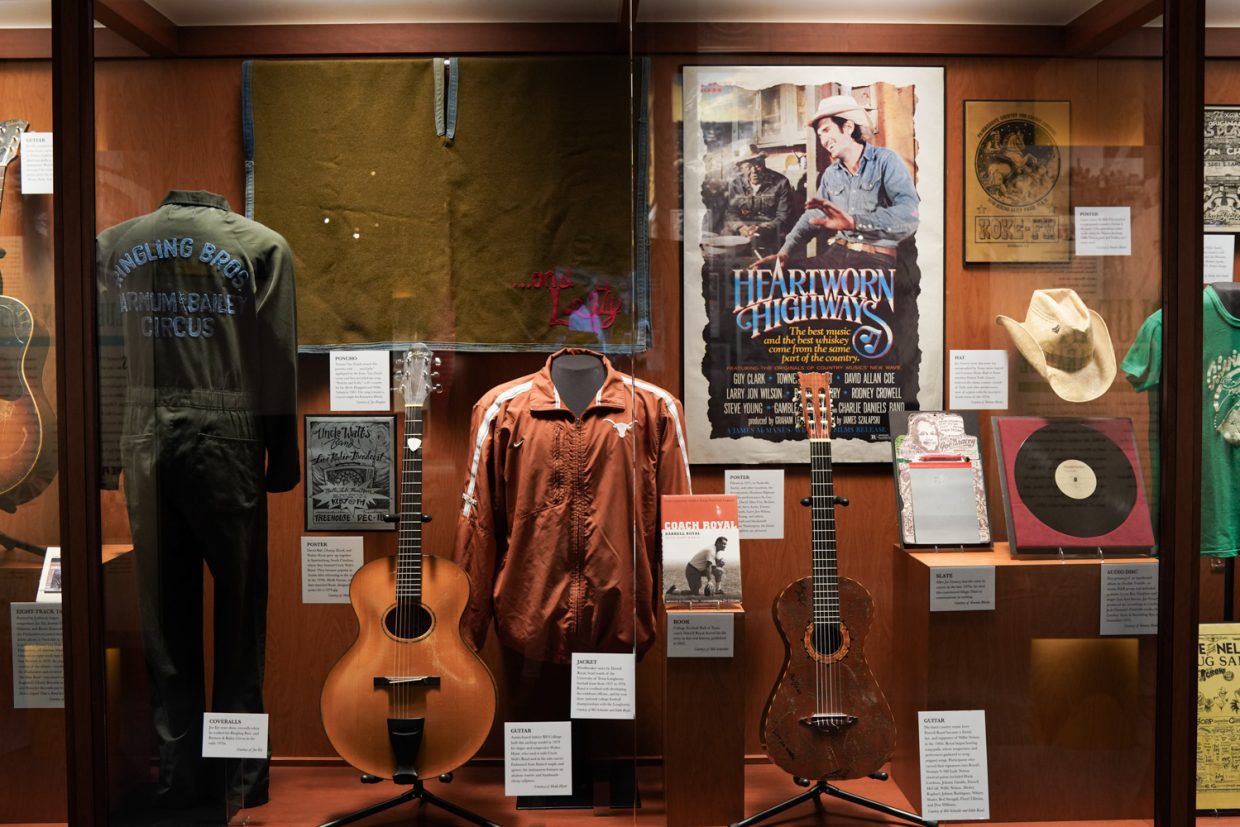

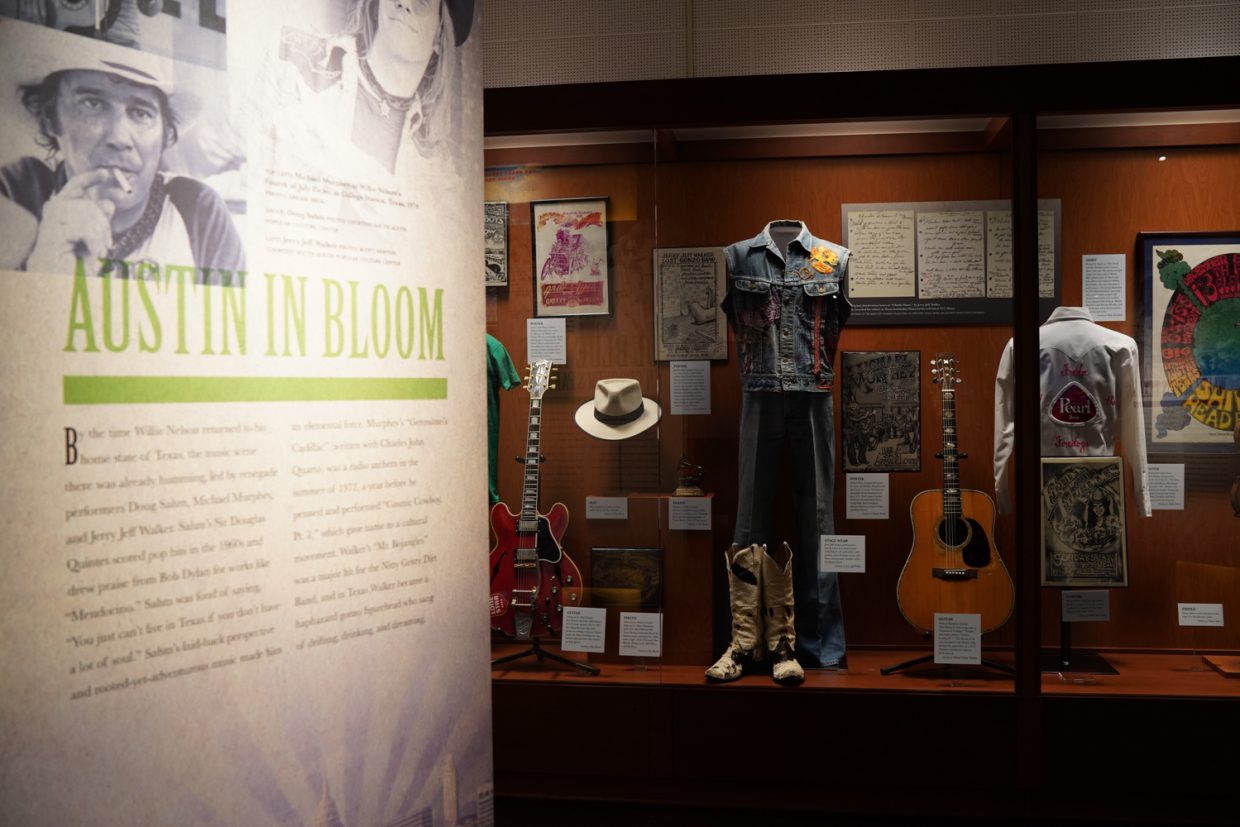

You’re from Texas, which has a pretty rich musical heritage. What Texas musicians were you into growing up?

I’ve had a really weird musical journey. I started out playing in church, kind of a natural path for any musician from the South. I’m super grateful to have all of that because it got me practiced playing with a band. It got me a lot of experiential stuff that I wouldn’t have learned, if I wasn’t playing every Sunday with a band or had to learn new songs all the time. No matter how good the songs were, they were still songs. So I did that, and once I was maybe 15, I got into rap a little bit — like Screwed Up Click, Houston rap … Paul Wall, Lil Flip, all of those kind of dudes. I don’t real listen to them anymore, but that’s just kinda how it went.

So your Texas influence is not necessarily a Texas country influence?

No, I was very like — I didn’t listen to punk rock, but I had a punk rock attitude when I was a kid. So, being from Texas, I didn’t want to like country music because that was like … everyone in Texas likes country music, so I wanted to go against the grain, you know? So I liked rap. I liked ZZ Top, or emo/screamo, or whatever it was. I didn’t start really listening to country music until I got sober almost seven years ago.

I mean I’d always kinda heard it. I knew a bunch of Garth Brooks songs. I knew a bunch of George Strait songs. You know, all those Texas country musicians — Robert Earl Keen, Jerry Jeff Walker. I knew those songs, but I had an aversion to the whole thing because of my punk rock sort of attitude. Then I kinda saw the light, I guess, and realized that it’s just what I related to the most.

Country, traditionally, has that whole thing about the primacy of the song, and you seem to be quite the songwriter type of guy.

I mean, whenever you get sober, you’re super raw and vulnerable and everything feels weird. So, really, through the three years that I was just a gnarly junky, I used being a musician as a reason to not have a job. Or I would get out my guitar every once in a while during an acid trip, and we would all freak out about it or something like that. I wasn’t really into it. Even in that phase, I was listening to electronic stuff. I got really into dubstep and Skrillex, so it just blows my mind thinking about it now, but in any case that’s where I was. When I got sober, I wanted to start writing songs, and I had all these weird feelings and vulnerabilities.

Did you feel like it was a way to get out all the weird emotional turmoil that comes with getting sober?

Yeah, exactly. And naturally I kind of gravitated toward more folk and singer/songwriter stuff because that’s where that kind of songwriting lies. And it wasn’t something that was necessarily foreign to me. It was just something that I kind of pushed away for a long time. But yeah, my first record was just like sad bastard, super depressing shit.

I can definitely hear the progression from Ephemeral through There Is No Map. And even that one is not quite as straight-ahead country as Concrete and Mud.

Yeah, I don’t know. Concrete and Mud definitely has it’s country tracks and what not, but I didn’t want to make a country record. Everyone and their mom is making a country record right now, so I wanted it to be … like, obviously that’s kinda the music I play — Americana, whatever you want to call it — but I wanted to have a uniqueness to it. I didn’t want it to just have pedal steel and some violins here and there. Though there’s nothing wrong with that.

You definitely have some weird sonic stuff going on that’s out of the box.

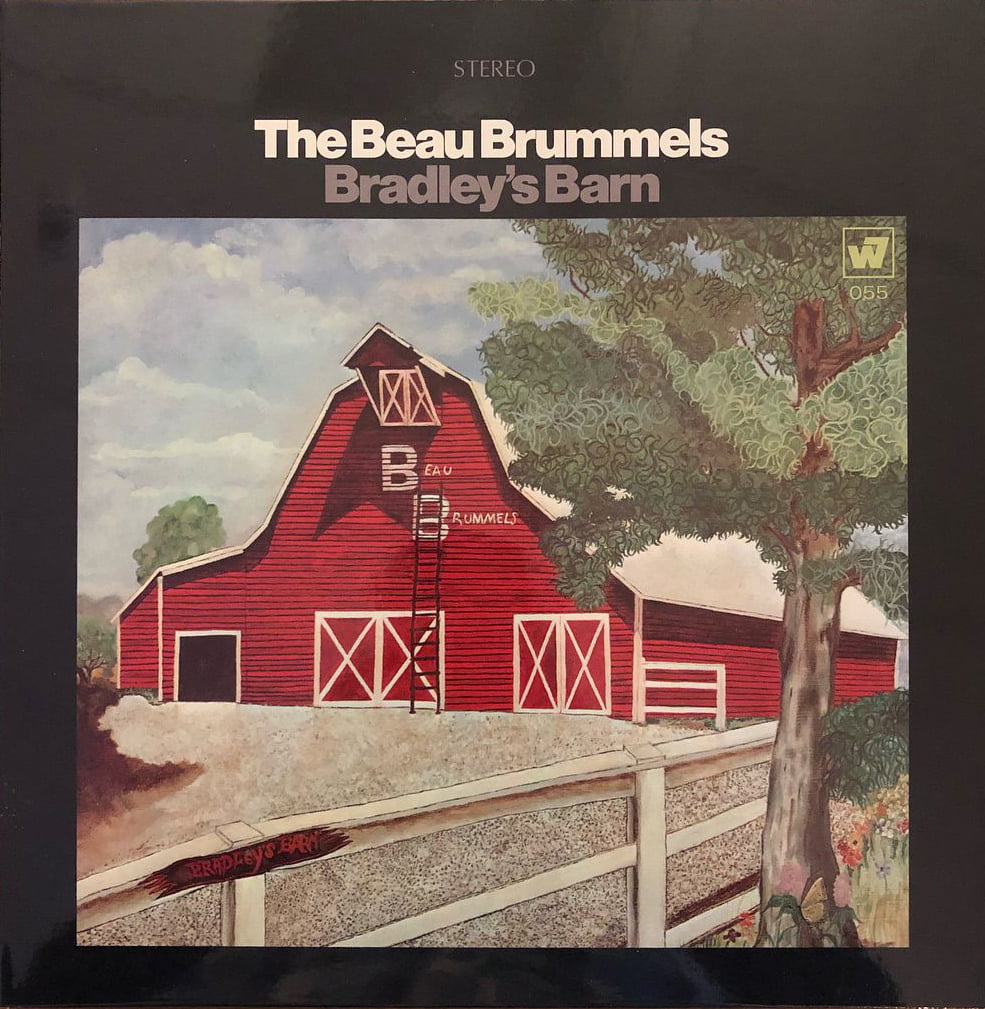

Right. I wanted it to get a little weird in some spots. Four years ago, I got super into Little Feat and started listening to a lot of deep Skynyrd stuff.

Is Little Feat kinda where the funk element came from?

Yeah, and I’m very groove-oriented when writing songs. If I’m sitting at a desk or something, I’m always banging on it. I don’t know. It’s just kinda there. I’ve just kinda always had that funky element. One of my favorite things to see is people actually dancing to the music I play live. And a lot of the country covers I was doing, like Don Williams, I consider him like country disco. Even Willie Nelson’s Shotgun Willie, it’s pretty funky that record.

Going back to what you said about the dance thing, you never get people dancing to sad bastard music. So what was the turn for you? Did you suddenly discover your love for groove? What happened there? Because it’s a pretty hard turn.

Going on the road and playing more bar gigs, like, “Here, we’ll give you this much money to play three 45-minute sets,” or something like that … I don’t have that many original songs. And also just seeing how people would respond to my sad bastard stuff in a weird bar where people are trying to eat their pizza and shit. So I learned covers that had a good groove or were a little funky, or I could put my own twist on and make it groovy and funky. And a lot of the songs on this record are just grooves that I took from covers that I’ve been playing for the last two years. And to answer your question: I don’t know if I really did. I just kinda hit that point where I was playing songs that people were dancing to and I was like, “Oh, this is what I like to do.”

So it was a response to the joy that you witnessed?

Yeah, just people having fun. I’m not really a dancer, but I can dance with my guitar in my hand. That’s about it.

There are some serious themes on this record, but you have a lighter approach to those themes. Was that a conscious move? Do you think about being sincere without being too sentimental?

Right, yeah that was, of course, intentional. I was definitely conscious to make this record lighter and sort of more sarcastic. I almost didn’t even understand that you could do that — that songs could mean a lot but be light or sarcastic or whatever. I could have never written “Quick Fix” six years ago, just poking fun at all my vices, noticing all my vices in everyday life. That’s not something I would want to point out — my flaws — even now, and make fun of. Maybe “make fun of” is not the right word, but make light of them or talk about them in a naïve sort of light.

You’re sober, which to me says that you take care of yourself, but then you sing a song like “Quick Fix,” and it makes me think that you’re not heavy-handed about the way that you take care of yourself, or prescriptive or preachy in some kind of way. Right?

Right. I mean, I still do a lot of shit. Like I play poker all the time. I’m super impulsive. I still have these addictive behaviors, but I’m in control and I recognize them. I keep them somewhat healthy. And that’s just a sign of maturity, I guess.

Kind of like, if you can wink at them, you’re giving them less power?

Yeah, exactly.

You nod to some funky and psychedelic country sounds, but then, at times, you take them a bit further. What made you decide to push the sonic envelope, so to speak?

I think we tried to do that on a couple tracks on the last record, but just didn’t quite get there or didn’t think it out enough. For instance, on “Paid by the Mile,” we initially had my phaser pedal on my guitar, and I was like, “This sounds cool, but how many people have put a phaser pedal on a guitar? Everyone fucking does it. Why don’t we try to put the phaser pedal on the Wurly?” So that’s what we did. We put the phaser pedal on the Wurlitzer, and it sounded fucking killer. And it still gives the whole mix that phasey, wobbly thing, but it’s just coming from a different place than where you normally hear it in a guitar.

So me and Eric [producer Eric Corne] both were willing to take more chances, I guess, this record. And the guy that plays keys — his name is Sasha Smith — what I really love about the way he plays keys is, he’s so percussive and rhythmic that it couldn’t have been a better person to play on this record. He fills in all the spots and uses whatever he’s playing like a rhythm instrument.

Yeah, even the organ on “Weight of a Stone” is so precise and punchy that it works like a rhythm instrument.

Right, exactly. And yeah, we took influence from … have you ever seen Peaky Blinders? So the Nick Cave song that’s the show credits opener…

“Red Right Hand”?

Yeah, so we wrote the song, and it’s sort of a murder ballad sort of song, but we wanted it to be sort of droney and have a keyboard theme in it. It’s pretty close to it. I don’t know how many people I should tell that we took it from that, but it’s far enough apart.

You do have a way of nodding to influences without aping them. There are some nods to Gram Parsons, for example, like the amphetamine queen line in “Coming Home.” Is that an homage to “Return of the Grievous Angel”?

That’s kinda where it came from. I don’t remember if I exactly took it from that. I think I just wanted to use “amphetamine” in a song. Like Jason Isbell uses “benzodiazepine” …

Yeah! How does he do that?!

I know! Dude! And it’s so perfect, too, the way he phrases it and everything is so perfect. So I wanted to have an elongated, full drug name in one of the songs and it just kinda fit. But yeah, Gram Parsons … “Skinny Elvis,” we referenced pretty closely “Ooh Las Vegas.”

Right, but Concrete and Mud doesn’t sound like a Gram record at all.

And that’s what we wanted. I was a little bit worried about “Quick Fix.” At first, I was resistant to the Clavinet because I didn’t want it to sound too much like “Cripple Creek” [by the Band], but then we started playing it, and it just didn’t sound as good without the Clav, so we were just like, “Aw, fuck it.”

To quote our mutual friend Jaime Wyatt, “Texans like to sing the shit out of a song.” What happened to your vocal performance? You’re earlier stuff is good, but you sound like a completely different vocalist on this record. You’ve got a level of control that I’d say is as good and as professional as it gets.

Thanks! I really appreciate that. Yeah, I think just playing out a lot. I’d never really taken a guitar lesson or a voice lesson, and I took a few voice lessons in the past couple years just to kind of understand my voice a little bit. And since my first record, I was playing with a friend doing a show four or five years ago, and we were playing this song and he said, “Why don’t you add some growl to this part? You can do that.” And I was like, “I don’t really have a growl to my voice, man.” And he was 100 percent right. My voice is like 98 percent growl, just like howling and seeing what comes out, and I just didn’t realize that until he said that to me.

So that’s kinda shaped my tone a little bit, too. And then I sorta started growling and yelling too much, so it was a matter of honing that in a little bit, and I think I’ve found a balance. Once you figure out you can do a new trick, you just do it all the time.

You do that really well at the top of the chorus on “Weight of a Stone.” There’s a lot of power in the attack. It’s really cool, one of my favorite moments on the record.

That one, we were a little bit worried when we first started. That was the hardest one to sing in the studio, for some reason. I think it was just a weird key or something for me. Initially we wanted to keep that song kinda soft. I even toyed a little bit with doing it falsetto, but once we got that kind of cool growl in there, it sounded a lot more epic, I guess.

One more thing: I’ve seen a term thrown around a lot lately, and it’s been used of you, and I wondered if you have any thoughts about it — “left-of-center country.” Does that mean anything to you?

Honestly, it doesn’t mean anything to me. Cool, you can call it whatever you want. You know, when people ask me what kind of music I play, I say country music just because it’s easy. You don’t have to sit there and explain it to them. Although these days you kinda have to explain to most people that it’s not the kind of shit you hear on the radio. A lot of lay people don’t know what Americana music is. When you say “Southern rock,” they don’t know what you’re talking about. You can call it whatever you want. We just made the record that we wanted to make, and we’re happy with the way it turned out.