“No,” says Tanya Haden, to a question pertaining to the new album she and sisters Petra and Rachel have made. “We don’t yodel.”

She thinks about it a second, as her siblings, sitting to her left around a right-angle sectional in the living room of her Los Angeles home, watch her warily.

“We kind of pretend-yodel sometimes,” she says.

To prove her point, she lets out a half-hearted yodel-ay-eee, to mild laughter.

The subject came up because there are a few songs on the Haden Triplets’ new album, The Family Songbook, in which yodeling would not have been out of place. These songs — “Who Will You Love,” “Ozark Moon,” “Gray Mother Dreaming” and “Memories of Will Rogers” — were written in western style by their grandfather, Carl E. Haden, and were very likely sung by the family band he oversaw.

That included their dad, Charlie Haden, who went on to be one of the most respected and influential jazz double-bassists of the modern era, working with Ornette Coleman, Keith Jarrett and his own groundbreaking groups. But back then he was a very young (and yes, yodeling) tot billed as Little Cowboy Charlie, held up by his mom to the microphone of radio station KWTO, “Keep Watching The Ozarks,” in Springfield, Missouri.

Those songs form the heart of the album, through which the sisters evoke the spirit of that legacy, filling it out with an array of folk/gospel/country/old-timey tunes that were quite likely in the family group’s repertoire. This follow-up to the first album they did together, 2014’s The Haden Triplets, draws heavily on stories passed down of those radio days.

That comes through strongly in such chestnuts as “Wildwood Flower” (the signature song of Mother Maybelle Carter, who rocked young Charlie as a baby when the Carters and Hadens hung out together), “I’ll Fly Away,” “Flee as a Bird” and an incredibly moving version of the gospel challenge “What Will You Give,” all likely part of the old Haden Family repertoire. Connecting this to current times, there’s a beautiful version of “Every Time I Try” (written by the triplets’ older brother Josh, who leads the band Spain) and, more of a wild card, a gorgeous take on Kanye West’s “Say You Will.”

The idea was not to recreate the old days, but to interpret and pay homage. The result is a lovely set of songs full of atmosphere, with contributions from, among others, guitarists Bill Frisell, Greg Leisz, and Doyle Bramhall II, bassists David Piltch and Don Was (as well as Josh on “Every Time I Try”) and drummer Jay Bellerose, all under the watch of producer Woody Jackson.

Yodel or no, they give their grandpa’s songs a tremendously vibrant run, centering on the evanescent harmony blends that can only come from siblings (and, specifically in their case, triplets).

“Those were the most straightforward songs,” says Tanya, who notes that she tends to be the most talkative in the group interviews.

“That’s more like the hillbilly songs on the first record,” Petra adds.

Yes. But figuring out how to approach them was a bit tricky. For most of the songs on the album, there are recorded versions on which to model, some of them many versions. Not these four.

“They’d never been recorded,” Tanya notes. “So we’d never heard them. We only had the sheet music.”

They’d heard a couple of recordings by the Haden Family, though no transcriptions of the regular radio broadcasts seem to exist. After a lot of research hoping to come up with something they did find some KWTO pamphlets and flyers with photos of their ancestors. But little else.

So they made their best guesses as to how best to evoke the aura of those times, with their own sensibilities. The result on those four songs is a sort of cowgirl-harmony effect — you could almost picture the three of them in gingham and ranch hats, leaning against a split-rail fence as they sing.

They’re not sure how their father, who died in in 2014 just months after the triplets released their first album, would have assessed it, though.

“If our dad was around, he probably would have said, ‘Oh no, you don’t do it like that,’” Tanya says.

But they got a strong thumbs-up from their uncle, Carl Jr., who was also part of the family group.

“I sent Carl Jr. the CD and he said he loved it,” Petra says. “He said it brought him to tears.”

Tears also figured into the choice of Josh’s “Every Time I Try,” originally on the 1999 Spain album She Haunts My Dreams, and used by director Wim Wenders in the soundtrack of his movie, The End of Violence.

“[Josh is] such a good songwriter,” says Tanya.

Petra adds, “Our dad used to say all the time that Josh should be rich and famous through that.”

“When he wrote that song, I just related to it so well,” says Tanya. “It’s [about] a relationship that is push and pull. I just love that song. It’s so beautiful. I remember when we were listening to it for the first time. He was all excited, and our grandfather on our mom’s side was listening to it. And he just teared up. He was crying.”

“I hope we did it justice,” says Rachel.

“Because I feel like it’s got this quietness when Josh sings it,” says Tanya. “But it’s hard to get with the three of us.”

And that leads to a key question. Given their close tie to their family, given their family history and given that they’ve been singing together pretty much since the moment they left their mother’s womb: Why did it take them so long to make an album as the Haden Triplets — they were 42 at the time — and why is this only the second one?

The fact is, Petra, Rachel, and Tanya are very different people, with very different lives. Petra has in recent years been in demand as a singer and violinist with artists from Bill Frisell (a frequent collaborator and guest on the album) to the Decemberists, as well as her own covers projects in which she recreates elaborate arrangements of classic songs all with her own layered voice. Rachel, a bassist, has been in various bands, currently including the reunited L.A. indie band, that dog (which, in its original form also included Petra). Tanya, a cellist who has played regularly with Silversun Pickups and numerous other L.A. bands, is mostly active as a visual artist and the mom of two boys.

“It took us a while,” says Tanya. “Between the three of us, we’re so busy. And we’re not like, you know, take the reins and say, ‘Let’s do this.’”

She pauses for a second.

“We also tend to fight a lot.”

Petra and Rachel laugh knowing laughs.

“We all give each other wounds — flesh wounds,” Tanya explains. “It’s hard to work together and get along.”

This is, of course, no surprise to anyone with siblings. Or who is the parent of siblings. Or who knows anyone who has siblings. But those differences are key to making the harmonies on these songs that can only be made by siblings, and here could only be made by triplets. That’s the signature of this album as much as the last one. Pointedly, the album begins with a somberly atmospheric version of the American standard “Wayfaring Stranger,” sung not in harmony, but in unison, the three voices together as one.

That proved a bigger challenge than doing the complex harmonies.

“Yeah, it is really hard,” Petra says.

It happened not so much by design, Rachel starting working out a melody for herself to start.

“Then Petra automatically started singing it too,” Rachel says. “And then it was like, ‘Oh darn! It started!”

“It started to sound good!” Petra says. “It was like, ‘Wow, this sounds really pretty.’”

“And on it there are moments where we’re not singing it exactly on time, you know,” Tanya says. “But it just shows we’re human.”

“It always feels great to come home,” Petra says.

“Come home to the family,” Tanya adds. “There’s nothing like singing with your siblings. We’re all locked in and we sound great together. And I do a lot of singing with other people, but it’s with my sisters that is most special to me.”

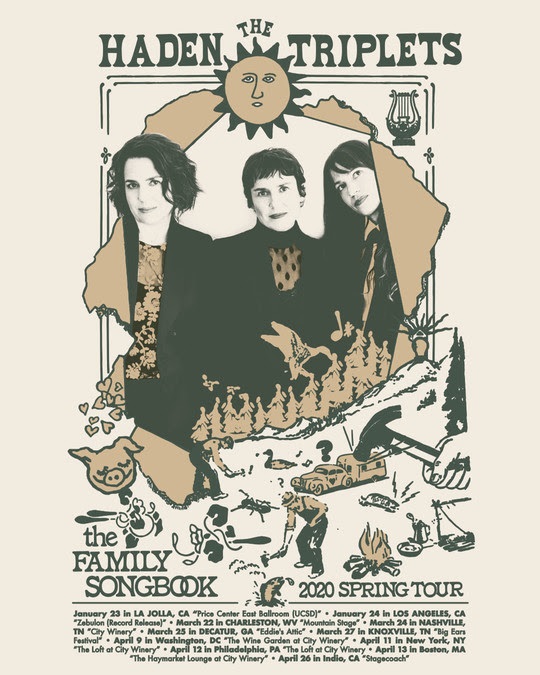

Photo credit: Shervin Lainez