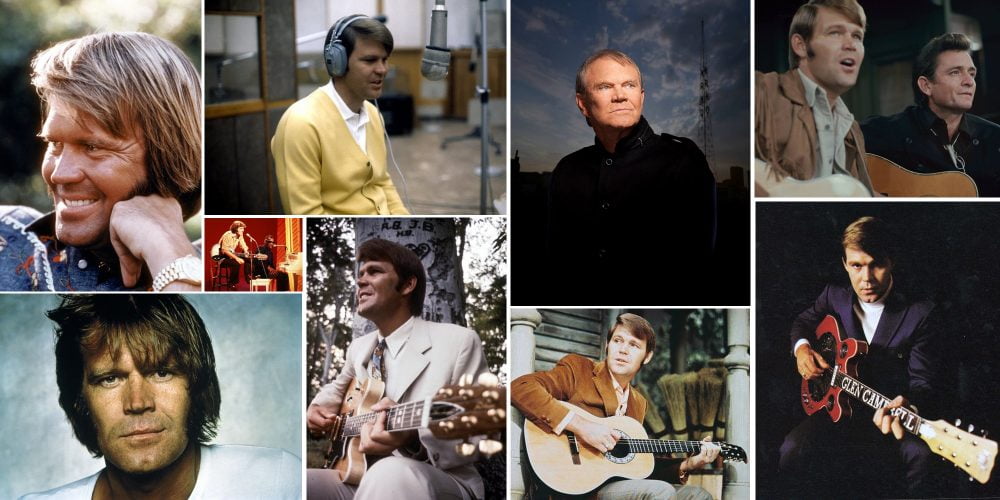

In the wake of his Alzheimer’s diagnosis in 2011, country legend Glen Campbell embarked on a Goodbye Tour, released a documentary film titled I’ll Be Me, and — in true Rhinestone Cowboy fashion — went back into the studio. The result is his final album, Adiós, out earlier this month. Produced by long-time friend and banjo player, Carl Jackson, alongside Campbell’s wife and children, Adiós is a collection of Campbell’s favorite songs and the career touchstones that he hadn’t gotten around to recording in the past. Highlights abound at every sonic turn, from Campbell’s children harmonizing on “Postcard from Paris” and his rendition of Bob Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” to his duet with Willie Nelson on Nelson’s classic “Funny How Time Slips Away,” Vince Gill’s feature on the Roger Miller tune “Am I All Alone (Or Is It Only Me),” and Campbell and Jackson’s interplay on “Everybody’s Talkin’,” which the two performed together on the Sonny & Cher Show in 1973. The constant through line is Campbell’s signature croon.

While his memory and ability to play guitar were already deteriorating by the time these sessions began, he channeled the songs with the help of Jackson, who printed out the lyrics in large print and walked him through the process line by line. Wrought with heart and grit, Adiós is a celebration that solidifies Campbell’s legacy and serves as a testament to the essence of the Rhinestone Cowboy: his voice. “[Glen’s] in Nashville now and he’s very well taken care of at a wonderful facility and he can’t communicate, but you go see him and he still sings,” Jackson says. “He still sings. It was his life. You can’t understand what he’s saying, the lyrics, you know, because he can’t communicate, but the tone is there. It’s an amazing thing. He’ll never stop singing, I don’t believe.”

You first met Glen and joined the band when you were 18 years old. Those are formative years, your late teens and 20s. Would you say that you came into your own while on tour with Glen? What did you learn from him?

It certainly continued, the growing up process. I had been with Jim and Jesse since I was 14, so I had a lot of experience from being out on the road already. But going with Glen, gosh, it was one of the greatest things that could have ever happened to me. He was such a great entertainer, singer, guitarist — just the best. I mean, I always tell people he’s absolutely the best singer I’ve ever heard in my life, just amazing talent, and on top of that, such a good person, such a good man. Glen and I became family almost instantly. I mean, it was just a mutual respect and love for each other that carried on all through all of these years. I traveled the road with Glen for 12 years, from 1972 to 1984, but that friendship and love has continued on all these years. And to get to do this final project with him just means more to me than I know how to say, really.

But yes, it was a very formative time and a great time. We were all over the world together, playing music literally all over the world, and I tell people — and this is true also — Glen featured me on every show we ever did. I mean he would bring me out front: He actually would leave the stage and introduce me, and he would always say, “Here’s the world’s greatest banjo player.” Whether that was true or not, I did my best to live up to it at the time. He was so good to me and he put me in front of millions of people, and it just meant the world to me, and I’ll always treasure those times. I could go on and on, obviously, about those times, so I’m gonna leave it at that.

Let’s talk about “Arkansas Farmboy.” That’s one that you wrote back on one of those tours, right, that you were on with Glen?

Well, it was during that time. I wrote it some time in the mid- to late-70s while I was with Glen. I mean, we went overseas many, many, many times, but I believe it was on a flight to Australia. I know we were over the Pacific Ocean. I know that. Glen told me a story about his grandaddy teaching him how to play “In the Pines” on a $5 Sears and Roebuck guitar. And I just thought that was the coolest thing that he remembered that precisely and I just got to thinking about how that little $5 guitar led to an absolute fortune and worldwide fame and stardom — just from one little $5 guitar. And it gave me the idea for the song and the title, “Arkansas Farmboy,” that just was kind of natural. That just kind of fell out because that’s what Glen was and is, to this day. I mean, Glen never left his country roots and his down-home upbringing. He never left that. He was Glen Campbell, country boy. I mean, you met him and he was the same, always. He treated everybody the same whether it was somebody waiting on us at a restaurant or if it was the Queen of England. It didn’t matter. He treated everybody with the same respect and love. He’s just the greatest.

What was the timeline for recording this record?

It was done over a period of time. It was after the Goodbye Tour. It was pretty well after when some people thought it was pretty impossible to get anything from Glen. But he wanted to do it so much and it was, again, that love and family thing made this possible. There was so much trust and love between me and Glen. Honestly, and I don’t say it — I don’t want it to come out in any boastful manner at all ’cause that’s not what I’m saying. There was just so much love and respect in the room, and Glen trusted me so much that I believe I was able to get things out of him that probably couldn’t have been done by anybody else and it was with joy. I mean, we laughed so much in the studio and had so much fun that it was just, I don’t know, I treasure it. And I know Glen did, too, at the time and as long as he possibly could remember it. I know he would be proud right now. I know he would. And that means more to me than anything. I wanted Glen to go out absolutely on a mountain — you know, on a high.

You just hit on this a little bit, but what was the atmosphere in the studio like during recording? Was it joyful or somber, or both?

There was no somberness, and I say that honestly. I mean, he was smiling and laughing and making jokes about himself like he always did and, if he forgot something, he just laughed about it and we did it again. He had to read the lyrics, sometimes one line at a time, but it didn’t change that perfect pitch that he retained through everything and that perfect sense of timing and that beautiful tone of his voice. The thing that went first was him being able to remember lyrics. He couldn’t do that. He couldn’t sing a song straight through and remember everything. He couldn’t play guitar anymore straight through a song. But I was able to get it and because I knew him so well, I knew his phrasing. And also, the fact that he was familiar — as familiar as he could be — with the songs that we did. These were songs that he loved his whole life, so they were ingrained in his mind still, as much as anything could possibly be, if that makes any sense. So we purposefully sat together and found songs that he truly wanted to record that he had never gotten to record before.

I love the snippet of Roger [Miller] before “Am I All Alone.” Where did that recording come from? Is it from a cassette that Glen has?

Yes, that was a cassette that Kim, Glen’s wife, she had kept that all these years. Roger played that for Glen the first time he heard it at Roger’s house in Santa Fe, New Mexico, over 30 years ago. Kim had kept the tape and she gave it to me, and we thought it would be a really cool idea just to let Roger introduce the song that way, because that’s literally the first time Glen had ever heard the song and he remembered it all these years and always loved it, but just never got around to cutting it before. So it was just one of those things, “Hey, we have to do this song!” You know, he’d pick up his guitar all through the years and sing a little bit of that song. And there were others like that — “A Thing Called Love” and “She Thinks I Still Care” and “Don’t Think Twice.” He rarely picked up a guitar without playing some of those licks off of “Don’t Think Twice.”

That’s my favorite Dylan song. I like what y’all did with the beginning.

It lent from Jerry Reed’s version. Jerry showed Glen that lick on the guitar that he put on his version of it, and then Glen showed it to me and passed it on. Glen showed it to [his daughter] Ashley. It’s carried on down through the years, so we kind of leaned on Jerry’s version there a little bit because that’s the version that Glen loved so much, so I kind of did the guitar solo stuff similar to Jerry’s version.

What was it like having Willie [Nelson] in the studio?

[Laughs] Well, I’ve been blessed to work with Willie several times over the years but, as always, it was fun. It’s fun to be together with him. I mean, he keeps things light and joyful, jokingly. Willie’s one of those troopers — one of those guys that that’s all he’s ever done and he loves it so much. I mean, he really wanted to be a part of it. When he heard that I had cut the song and he heard the version that I had cut, he was happy to be a part of it, and I just thought it would be a really cool idea because Glen, again, sang that song for so many years and he never cut it. We would sing it on stage. I mean, we would do it on stage a lot, when I was with him, and he would just occasionally bring it out, just, “Hey, let’s do ‘Funny How Time Slips Away,'” and he’d just start singing it. So it was, again, kind of a natural to do. And I had played some of the early stuff I had when I cut the tracks, I played them for Buddy Cannon, who’s a friend of mine and Willie’s producer, and he said, “Man, I’ve gotta play this for Willie. He’s gonna love it!” And I said, “Well, do you reckon that Willie would wanna play on it and sing on it a little bit?” He said, “Aw, man, I’ll bet he would.” And sure enough, when Willie heard it, he loved it and so it was a joy. You asked me how it was: It was a joy.

You also had Vince Gill as a guest on the record. Did he come into the studio to record or was that done at a later time?

Well, there’s so much history there, too, with me and Vince together. That was a natural thing, too, and I’ll tell you how that happened: Vince and I have worked together so much over the years. We did the Angel Band record together with Emmylou [Harris]. Gosh, I sang on “Oh, Carolina” — a couple things on Vince’s very first EP, when he got his first deal on RCA. I mean, we go back a long way. We’ve been friends a long time and, pretty much every project I do, I always ask Vince if he wants to be a part of it. And so, I was over at his house and we actually were working on the Orthophonic Joy project that I produced — the tribute to The Bristol Sessions. We were working on that, and I told him that I was gonna do this stuff on Glen, and we got to talking and it came up that he had never, as many people as Vince had got to sing with, he had never gotten the opportunity to sing with Glen. I said, “Well, buddy, I’m gonna give you the opportunity to sing with Glen.” So I made sure that I saved a part for Vince to do, and he told me it was just one of the thrills of his life to get to sing with Glen Campbell. So I wanted to make that happen not only for Glen, but also for Vince. And plus, nobody can sing it better than Vince anyway.

It really did fulfill a dream for Vince, too, and I certainly wanted it to happen. And he’s a dear friend, so that one was easy. I took it over to Vince’s house. We didn’t do it at the same time, obviously. We overdubbed it at Vince’s house, but I am happy it happened and, once again, I know that one of these days, when Glen is listening from up above, he’ll be very proud of that, very happy that we did that.

When it came to incorporating Glen’s children, how did you land on “Postcard from Paris” and that particular line for them?

First of all, it’s another great Jimmy Webb song that Glen absolutely loved and I absolutely loved. I was familiar with the song from Jimmy’s record. He did a record produced by Linda Ronstadt years ago called Suspending Disbelief and it had that song on it and it had “Just Like Always” on it and it had “It Won’t Bring Her Back” on it. Several of those songs, I was very familiar with and, of course, Glen loved the songs, too, so again, they were natural things to do. And “Postcard from Paris” was a very special song.

When we were cutting it, I didn’t think so much about the line, “Wish you were here,” as it kind of related to Glen’s condition. I mean, we didn’t cut it because of that. We just cut it because it was a great song. But then, after I cut it, I got to thinking, “Well, gosh, this would be a great one to have Ashley and Cal and Shannon sing harmony on.” And then, specifically, that line — it just makes it so emotional to hear because we do all still wish he was here. But that didn’t even come into anybody’s mind, when we picked the song, and neither did “Adiós.”

“Adiós” is just a great Jimmy Webb song that Glen and I love. He had never cut it before, and we decided to cut it, but we didn’t even think about it being the last song on the last album. That wasn’t a thought. Things like that just kind of fell into place and it seemed a natural thing to do then. When Universal picked up the album, I mean, I have to honestly tell you, I thought the album would be called Arkansas Farmboy. But when Universal picked the album up and decided they wanted to put it out and promote it, they immediately went to Adiós. And I’m like, “Well, okay, I understand that. I understand what you’re saying.” We didn’t even think that way, at first. I know I jumped from “Postcard from Paris” to “Adiós,” but it was a similar situation where those lines in “Postcard from Paris,” we didn’t do the song on purpose to pull at people’s hearts but, after the fact, it certainly pulled at people’s hearts.

Listening back, taking into consideration the circumstances, there’s a lot of dual meaning on this record. Even “Ain’t It Funny How Time Slips Away.”

I’m just like you, honey, when I listen to it now, I’m like, “Oh my gosh, listen to what that’s saying!” “Everybody’s Talkin'” is the same thing. We didn’t think about that. That was just a song that Glen loved and we were going through songs. I’m not ashamed of it at all, but I just feel like God’s hand is on the project and on Glen. The whole thing just came together, I truly believe, in the way that it was supposed to. Glen Campbell is just the best, and I mean that with all my heart. He’s the best singer that I’ve ever heard and I mean that technically, as well as just beautiful to my ear. His voice always was — and I realize people can have different things that they like and I’m sure there are people that would argue, “Oh, he’s the best” — but I’m talking not just how pleasing his voice was, but how great he was technically. I tell people to go find me a bad note on YouTube and I’ll pay ya for it. I mean, the guy, he was amazing. We cut live shows over in England, where we did a live TV show with a full orchestra and us as the main band — we did ’em live in front of a live audience to tape and I listen to ’em now and they literally sound like they’ve been tuned. The guy was amazing as a singer. Just perfection. And I know I could go on and on, but I could never say enough about him and about just how great he was. And I wanted people to still see that and still realize that, and I hope this album does that.

It truly is a gift.

To this point, every review I’ve seen and every interview I’ve done, people are so kind about this record and so, the word “gift” has been used so many times and that means the world to me because that’s exactly what we intended and what we wanted to give the world. We wanted to give ’em Glen Campbell — here he is just like always, once again. People tell me that, “Oh, he’s singing so great,” and I’m like, “Yeah, just like always!”

Ronnie McCoury, Vince Gill, Del McCoury

Ronnie McCoury, Vince Gill, Del McCoury The finale of the Grand Del Opry

The finale of the Grand Del Opry Sam Bush and Del McCoury

Sam Bush and Del McCoury The Travelin’ McCourys, Vassar McCoury, Del McCoury, and Dierks Bentley

The Travelin’ McCourys, Vassar McCoury, Del McCoury, and Dierks Bentley