If roots music has such a thing as a Renaissance man, there’s surely no stronger contender for the title than Jim Lauderdale. Some artists find a furrow and plow it deep, but Lauderdale has spent the better part of a lifetime ranging with abandon through enough fields to leave most of us out of breath just thinking about it. He’s a legit hit country songwriter; the recipient of an Americana Music Association award for lifetime achievement; a creditable actor who portrayed George Jones in a country music play; the regular host for Music City Roots, a long-running musical variety show; and an artist who’s written and recorded a long list of works ranging from Beatles-esque pop to rhythm & blues to old-school country, and appeared with an equally long list of masterful practitioners of them all.

But Jim Lauderdale is also a bluegrass guy—and not only because he’s recorded bluegrass albums with Ralph Stanley & the Clinch Mountain Boys, as well as a half-dozen or so on his own. The North Carolina native discovered the music while still in his teens, then immersed himself (starting with learning to play banjo) deeply enough that he can still speak with facility about a surprising number of the obscure records and regional acts that lurked behind the obvious attraction of marquee names like Stanley’s.

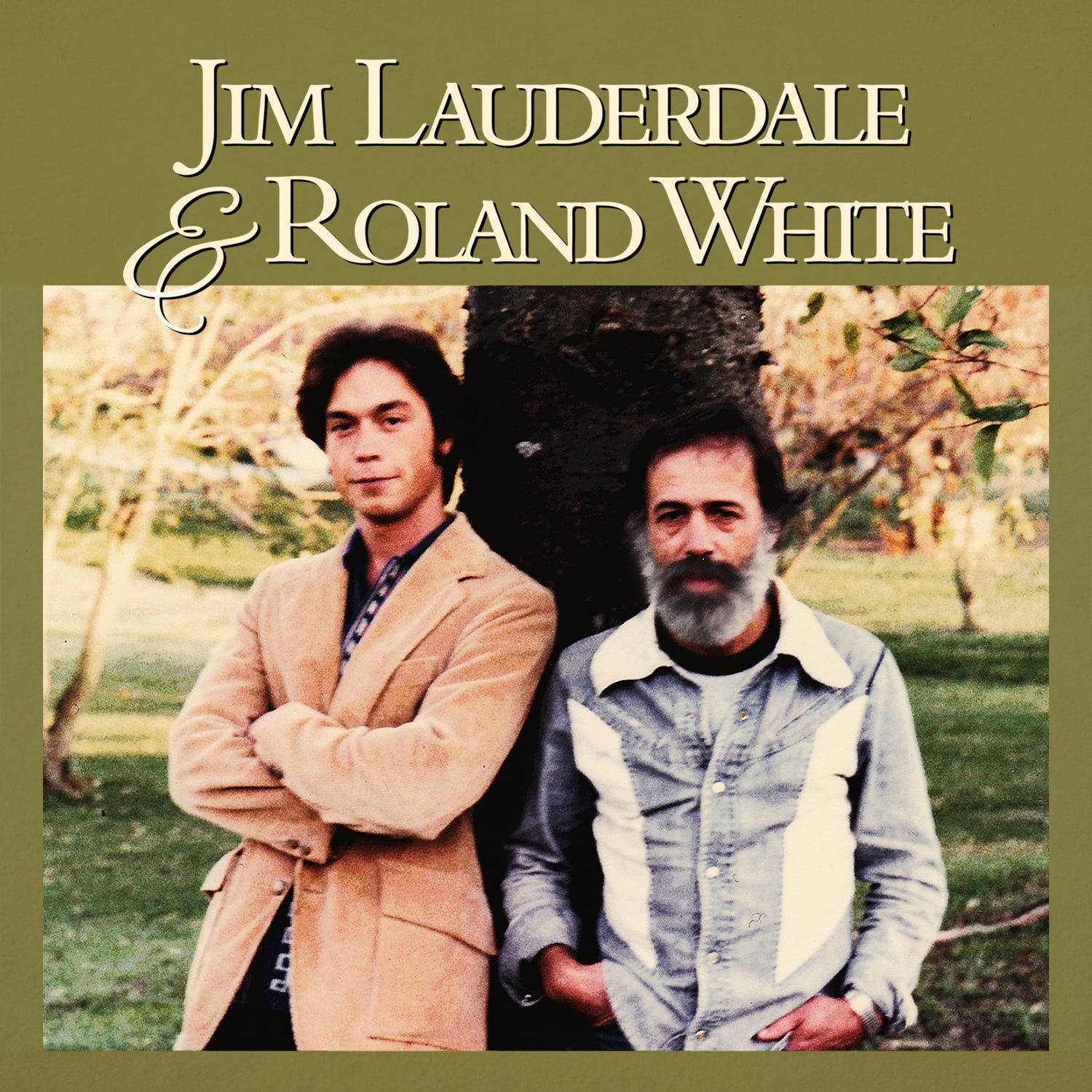

As he did so, he became acquainted with the music of our Artist of the Month, Roland White—and, as he related in this recent conversation, that led to making a 1979 album that just this summer finally saw the light of day. The appearance of Jim Lauderdale & Roland White (Yep Roc) is like a nifty little message from the past, reminding us of, among other things, the way that a kind heart and a welcoming attitude can shape not only our own lives, but those of others. Roland White was a hero to Jim Lauderdale in his youth, and he’s still a hero to Jim today. Let him tell you all about it….

You’ve told me that when you moved to Nashville in 1979, you had some goals in mind.

My two goals were to hang out with George Jones and Roland White—out of anybody in the world, those two guys.

Why was Roland on your radar?

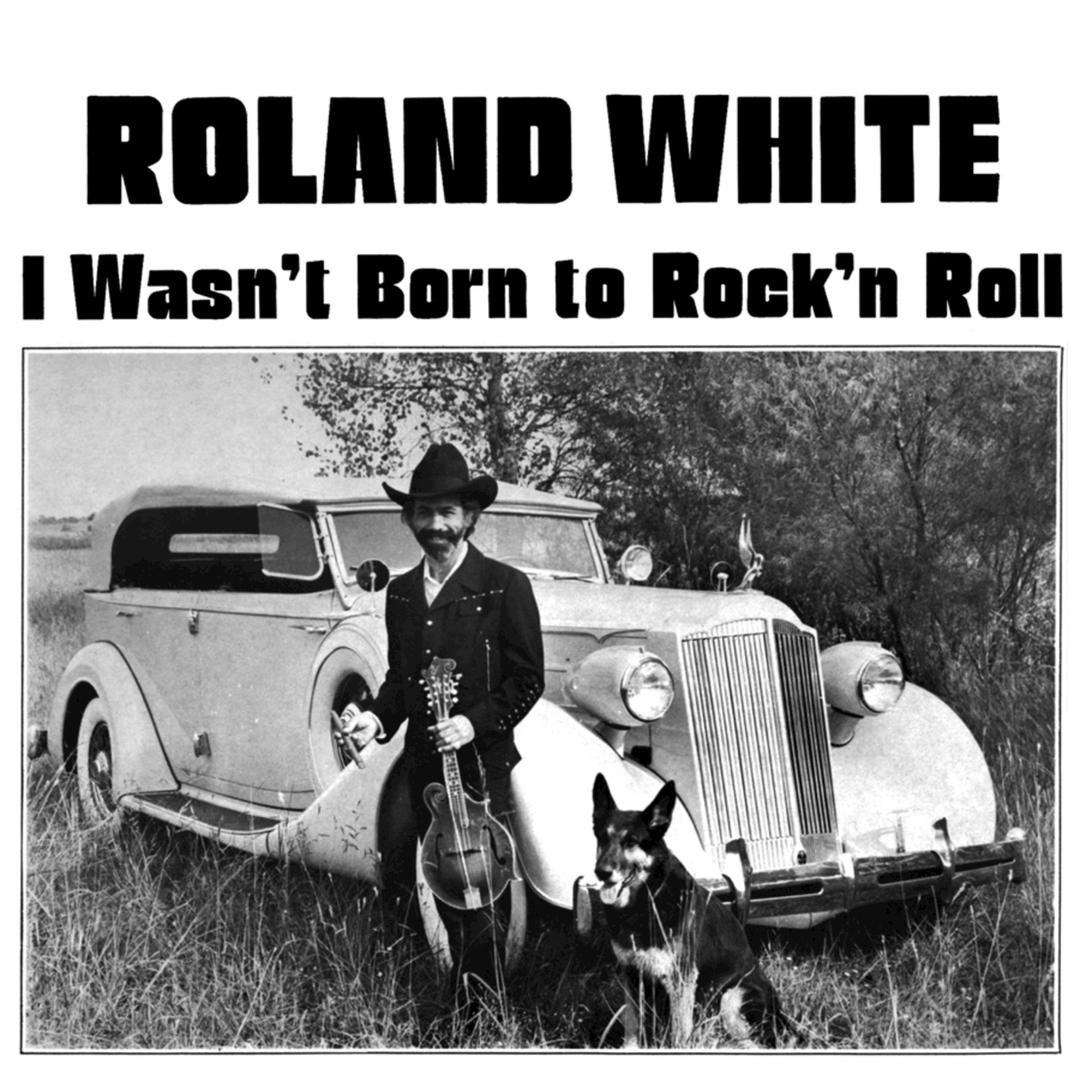

Because of the Kentucky Colonels—well, the Kentucky Colonels, and then shortly thereafter, Rounder Records put out that album of the White Brothers in Sweden. And then there was a Kentucky Colonels live record that came out, too. It was one of those things—I was playing banjo, and just a little bit of guitar, and I knew I’d never be able to play like Clarence White, but there was just something about Roland. He had so much soul to him, but he was still very understated. And then he put out that solo album, I Wasn’t Born To Rock’n’Roll.

So when I came here, I went to the Station Inn and saw him, and introduced myself and started up a conversation. He was just so nice and let me sit in. I started doing that more and more—going to the Station Inn any time he’d play—and he was just such a warm guy and really made me feel at ease. I was kind of nervous because he was kind of an iconic figure to me.

And then he said, “Come by the house sometime.” So I went by and we just jammed. One time—and I’ll never forget this, it might have been the first time I went to his house—I knocked on the door and hollered and he said, “Come on in, I’m back here in the music room.” So I went in, and there was this piano player playing on a record, and I said, “Who’s that?” He said, “That’s Thelonious Monk.” And I thought, well, I’ve heard of this guy, but I’ve never heard him.

And Roland, I’m sure his musical tastes and palate go way beyond what you can even imagine, yet in his style, he keeps things close to the vest. But also his singing, too, it’s got a real soulfulness about it. It’s just right, just like his playing. I think his playing is very unique and very adventurous, but always very tasteful.

That makes perfect sense, because Monk’s music has a lot of spaces in it, and Roland does that, too. So how’d you guys hatch this scheme of making this record?

Well, to begin with, I said to Roland that I’d like to do a demo of this new song I wrote called “Lazy Boy.” And I said I’d like to do a version of “I’m Gonna Sleep With One Eye Open” and “Ocean Of Diamonds.” So we went in with and cut those three songs.

I had worked one summer—I think it was after my freshman year in college—at Busch Gardens. I was in a bluegrass band that they kind of put together, and there was another band, too, called the Wahoo Revue. Stan Brown was the banjo player in that band, and then Gene Wooten was the Dobro player, and there was another guy who played bass named Gary Bailey. And when I came to Nashville for those five months, Gary and Gene were both playing with Wilma Lee Cooper, and I was roommates with them. So we cut those three songs with Stan and Gene, and Terry Smith playing bass, and Blaine Sprouse playing fiddle.

I couldn’t get anything going here publishing-wise at the time, and I didn’t know what to do, really, as far as trying to get a record deal went. To me, country music was Hank Williams, George Jones, Merle Haggard—those big Mt. Rushmore guys—Emmylou Harris, Tammy Wynette, Loretta Lynn—and in my mind, bluegrass goes right in there. They went hand in hand, like a brother and sister kind of thing. But even at that time, in 1979, there was a poppish element to the country charts that I wasn’t familiar with. So I just didn’t fit in and I couldn’t get anything going. And so the highlight for me, the huge highlight of my time in Nashville, was hanging out with Roland.

And I think it was Roland who suggested, “Well hey, why don’t we go in the studio and do a whole thing?” We already had those guys, but I guess Blaine wasn’t around, or maybe Roland just decided to get Johnny Warren to play fiddle. So we did it at what was then Scruggs Studio, in Earl’s basement. His son Steve engineered and Roland produced. And Earl would come down every day with a silver tray, and china, and coffee, and he was wearing an apron—it was just surreal. He was the nicest guy in the world, too, but I was still very tongue-tied.

And I remember the first day I went there, too, Red Allen was sitting there in the room, and that also made me nervous. But he just hung out for a little while. It was pretty low-key; we got a lot done pretty quick. And then there were some things that weren’t going to have banjo on them, and Roland said, “How would you feel about Marty Stuart coming and playing lead?” And I thought, great, because I’d seen Marty with Lester and Roland when I was 15. I thought he was the coolest guy, and he was real nice, too.

It’s an interesting set of songs, with a couple of originals. By that point, how long had you been writing?

I had been writing about four years, but I didn’t have too many bluegrass songs under my belt. “Forgive and Forget,” I wrote that fall before we went in, and the same with the other original, “Regrets and Mistakes.”

They were written with the record in mind?

Oh, yeah. And then Roland suggested some of the covers I did. Two that I wanted to do were Kentucky Colonels songs: “I Might Take You Back Again” and “(That’s What You Get) For Loving Me,” which was a cover they used to do. And I brought in the song “Gold and Silver,” which was a George Jones song. But Roland had the more interesting covers, like Donovan’s “Catch the Wind,” and “February Snow” that Lester Flatt had recorded.

As soon as I heard “Forgive and Forget,” I thought, that’s one of Jim’s. So even at that early point, you were developing something distinctive as a writer. Were you writing a lot at the time?

I was. I guess I was writing more country stuff, and more stuff of what we would now call Americana, but kind of a mixture. And even back then, if I did a solo gig, I’d bring my banjo and do some bluegrass; I played dobro a little bit, too, and I’d do some stuff on that, and some guitar stuff, and even some blues harmonica stuff. It was kind of eclectic.

So what happened then?

Well, we did the record, and then I left Nashville about a week later, and oddly enough, of all places to go, I chose New York City. But when I left, I had some cassettes of the record, and I sent them to the major bluegrass labels, with a very sloppily-written cover letter introducing myself, saying I’d like to be on your label. And every label wrote back and said, “Thanks, we like the record, but you’re an unknown, you’re not on the bluegrass circuit. Stay in touch and let us know what you’re doing over the years.” So that really bummed me out. I thought, this was it—this fantasy to record with Roland White and those guys had happened, and people don’t want it. So I kind of shelved it.

Eventually, I ended up in Los Angeles, and I finally got a country record deal. And the first one to come out was in 1991. So I contacted Roland and I said hey, I think now somebody’s going to want to put this thing out that we did. And he said, “Well, that’s great—you’ve got the master, right?” And I said, “I thought you had it.” So it was lost until he was at the Station Inn last year, and as he was leaving the stage, he said, “Oh, by the way, my wife found a tape at the bottom of a box that has our name on it.”

So Diane [Bouska] finds this tape, and they get it in some kind of listenable form…When was the last time before that that you had listened to the record?

It had probably been since 1980. I’d listened to it and I remember playing it for my grandmother in Lexington, Virginia. But I was so heartbroken that we couldn’t get a deal that it was hard to listen to, because I knew nothing was happening with it at that time. And then I misplaced the cassette I had. So it had been close to 39 years.

What did you think?

I was pleasantly surprised. It brought back so many memories, and just how much I loved the record when we made it—and how much I love it now.