The Wood Brothers have been together as long as they were apart. For fifteen years or so Chris and Oliver Wood pursued separate careers — Oliver out of Atlanta as a blues/rock guitarist and singer, and Chris out of New York as the bass player with the uncanny jazz/jam success story Medeski, Martin & Wood. Then they sat in together and felt a pull energized by family ties and musical curiosity, and their folk duo was born, about fifteen years ago.

Chris jokes that over seven studio albums and uncountable miles on the road, they’ve been on “a slow rise to the middle” but that’s far too self-deprecating. Their last opus, 2018’s One Drop of Truth, was nominated for a Grammy, and not long after it was released the band headlined the Ryman Auditorium and Red Rocks Amphitheatre (their hometown shrine, as they grew up in Boulder, Colorado). In September, they released their fourth live album, culling songs from a two-night stand at the Fillmore in San Francisco, where their highly developed musical telepathy — between the brothers and with drummer/keyboard player Jano Rix — was on vibrant display in a warm sonic atmosphere.

Newly minted is Kingdom In My Mind, an 11-song collection inspired largely by the feel of a new studio. The band and their sound engineer Brook Sutton had to move out of the old church-like studio where they’d made One Drop of Truth, but they found a new place nearby on Nashville’s west side. The brothers spoke to BGS about how that new destination shaped the sound of their latest project.

BGS: I understand that shaking down your new recording space produced proved unexpectedly productive?

Oliver: In our downtime we’ve always had some sort of rehearsal space, whether it was Chris’s basement or something, where we would just improvise and come up with musical ideas. I think all of us enjoy the art of improvising and playing music without thought and without purpose. We’re not trying to write a song. We’re not trying to sound good even. We’re just trying to play something new. Chris and I will react off each other, or off Jano, and do that musical communication that can happen if you just listen. We’ve always done that. And we’ve always recorded it on a phone or on a laptop just to remember. Whereas this time we set up and did the same process but we had a professional studio and an engineer miking everything up so it was usable.

Chris: Yeah, we didn’t know what we were doing. We didn’t know this was going to be the beginning of a record. We’d got a studio and put a lot of work into getting it up and running and sounding how we wanted it with baffles and things like that. But then it was, well, this is a huge room. Where do you set up? Where do you put the drums? Let’s put them over here. Let’s see what that sounds like. And we set up near each other and threw some mics up intuitively. I think we were struck immediately as soon as we heard playback. Even with that haphazard setup, it sounded great. Something about the room made us play a certain way. It felt magical and inspired. So immediately we looked at each other and said, “Maybe this is how we make this record.” So we did maybe five sessions where we set up and improvised in different parts of the studio. There’s a big A room, which you could almost fit an orchestra, and then a smaller, dryer room. So we had fun with all kinds of different variations.

Can you give us a visual and the background of the place and why it became home?

Chris: It’s an old print shop. So what we call the B room is smaller. It’s probably where people came in and got stuff photocopied.

Oliver: And then the back room — after it was a print shop and before we got it — was a dance studio with a dance floor and high ceilings. It was probably a warehouse at some point. This is not a fancy building. It’s cinder block.

So you had to look at this print shop/warehouse/dance studio and imagine a plan?

Chris: It was easy, and it had to do with the layout. It was very clear immediately. The control room goes here. From that room you have access to both tracking rooms. There’s even a lounge. There’s a room with a loading dock that can also be an isolation room. And it’s all in a circular layout. Everything about it was easy to imagine how we could be up and running quickly once we got our stuff in there.

Oliver: It was luck. And it was cheaper than we expected. But I’ll add to that process that Chris was talking about. The improvising we like so much, almost never can you use that stuff on an album. Normally you perform songs to make albums. So Chris got really good at editing these improvs. These are just jams, maybe in the key of A for 20 minutes. Maybe we switch chords every once in a while. Maybe we don’t. But Chris started chopping them up (in audio software). And we realized that we could arrange these improvisations.

And the beautiful thing — which usually gets lost — is your first impression of things. Like when you’re inspired. You play something, and you’ll never do it again. But we actually captured those moments and were able to use them on the album. And so the things that all of us love about albums are these anomalies, little mistakes or weird things that bleed together — things that if you were thinking about a song you’d never have played. To us, that had a freshness that Chris was able to chop up, and we were able to write lyrics over these new collage-y things.

Chris: Like Sly Stone said, there’s a rhythm when you don’t know what you’re doing. And we really take that to heart. I think that’s why a lot of musicians who have been doing this a long time really cherish first takes. Because before all the musicians really know the song, they’ll play things that they’d never play once they really know the song. For a lot of us, I mean for me certainly, it’s always a red flag when we do a take and I feel like I really nailed (it). It’s almost a guarantee that that’s not the take. Not the good one. The good one was the one before, when I was searching and didn’t quite know what was happening next.

Oliver: Discomfort is good.

Chris: A little bit, yeah. You don’t want to know too much.

Right out of the box on “Alabaster” there’s this over-driven sound like a Rhodes piano and I wonder if maybe that was just an accident that worked?

Oliver: Absolutely. That was recorded the first day we set up. Jano was playing drums and keyboard at the same time. He had this keyboard rig with a crappy little amplifier and it just sounded like that. And again, we weren’t thinking about a song at all. We were all in one room in a circle, and it just happened to be cool.

Chris: We were thinking sounds more than anything. Oliver had this great Stella guitar that he recently got set up. I’m sure Jano played that sound on purpose because he liked it. It was very intuitive and in the moment. So he didn’t have to worry if it was fitting a song or not. He just liked the sound. That’s kind of what we were going for.

You both come from improvised music backgrounds, one jazz and one blues-based. When I heard these tracks, I felt like the Medeski, Martin & Wood approach and the Wood Brothers approach have never been closer. Also, Jano plays with even more freedom. This feels like a jazz record in many ways.

Chris: I absolutely agree. This is the most meshed those worlds have ever been. It was definitely a long-term goal to get to this point. Little by little, not only integrating the MMW background with the songwriting, but also, just as you said, Jano is such a talent and can do so many things. Great drummer. Amazing keyboard player, percussionist. Great singer and producer. So to integrate all of his talents into what we were doing as a duo took some time, you know?

I think that’s why it works. When you improvise, all your knowledge, all the music that’s inside you, can come out. It’s not restricted by a song that’s been written already. Jano’s drumming and all of our playing is featured more because we were improvising to create the source material for the songs and were able to keep that. In the past I loved all the songs, but there’s a lot more that we can do. Improvising is a way to showcase that.

Oliver: It does inform how you play live too. We learned that you don’t always have to be right on the money. It’s fun to pretend like you’re in a punk band for a minute or something and kind of let loose and try something different.

Here it is about 15 years into this journey. Maybe it’s been an even bigger force in your lives than you thought. What have you learned, as musicians and family?

Oliver: I bet we take it for granted doing it all the time and being busy with it, but certainly in the last 15 years I feel like Chris and I were slightly estranged in that we were living in different places and playing with different people. We had sort of lost touch. So initially, yeah, the music brought us back together and we were able to combine our shared interests and experiences. That was awesome, and it was how we reconnected as brothers. And it’s nice to have a family business, especially a creative one, where we get to do that together and make a living too.

Chris: Yeah, people usually frame the beginning of this band as if it must have been a casual side project. But I never thought about it that way. It was exciting from the beginning. And for both of us, in different ways, coming full circle. We grew up with our dad playing music live around the house, you know, folk songs. Playing and singing. And that was, we realized, a huge influence.

I always liked singing when I was younger and ended up in Medeski, Martin & Wood, an instrumental band, for 20 years. I hadn’t been singing, so it was scary, but it was something I was really excited about getting into again. And just the way we write songs and composing with my brother is really fun and different. Whereas MMW was, as you said, a lot of improvisation, I also like writing. It was nice to get into that too.

Pulling back, MMW was a band that took real jazz to the jam band audience. And I feel like there are bands that hover between the world of the jam audience, which loves freedom and surprise, and the songwriter audience, which focuses more on the lyrical emotion. And maybe those bands never quite get totally accepted by either camp. How have you all mapped that?

Oliver: That’s well put, and I think we ride that fence, and enjoy it for the most part. It’s a nice balance. Personally I like to hear somewhere in the middle. I like to hear a good song, but I also like to hear some musical interplay. I think a balance of those things is really cool.

Chris: Yeah, one of the things that can be amazing about music is when there’s some mystery. You don’t quite understand what’s happening up there but it still is engaging. And how do you do that? There’s no formula. Nobody knows. Which is why we never get tired of this job. You know, you can’t figure it out. You stumble upon it sometimes, but it’s not always obvious how you get to that magical balance between the two.

Oliver: It’s always a fun challenge for us to take a good simple song but set it apart and give it its own sound. So use a weirder guitar. Use a broken thing. But make it something you haven’t done before and you haven’t heard somebody else do before. That’s kind of what we’re always doing.

We talk about this all the time. Sometimes we’ll write a song and use just cowboy chords and write it like a country song. Then [we’ll] mess up the music completely and make it our own thing somehow. So it’s a combination of all this classic stuff we love. And then, how can we make a new classic?

Craig Havighurst is host of The String from WMOT Roots Radio in Nashville and a longtime journalist covering roots music.

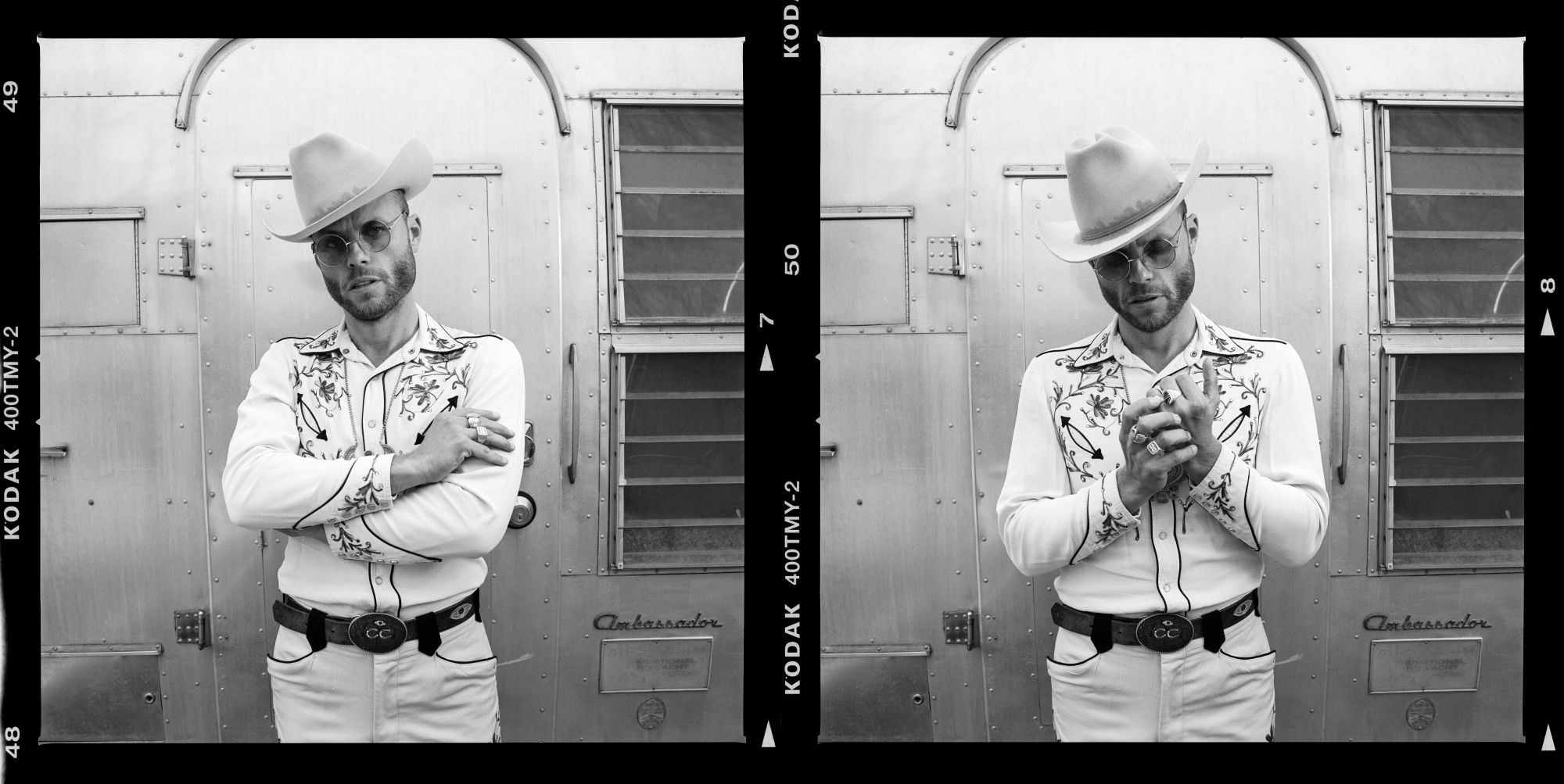

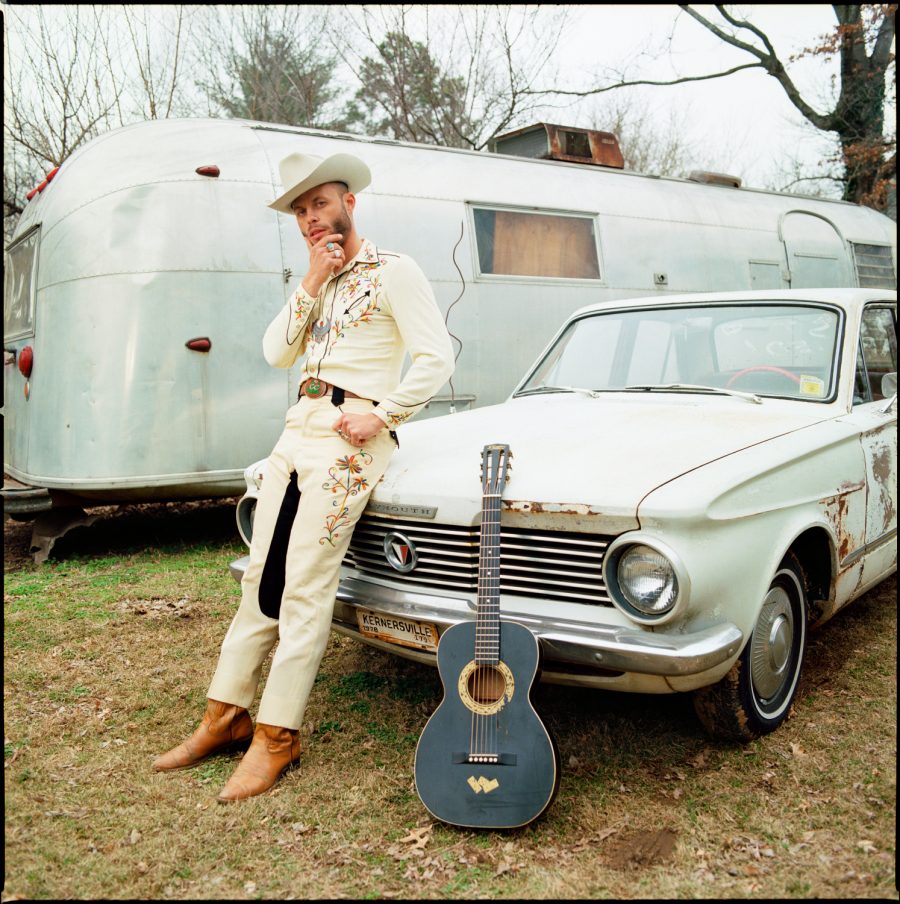

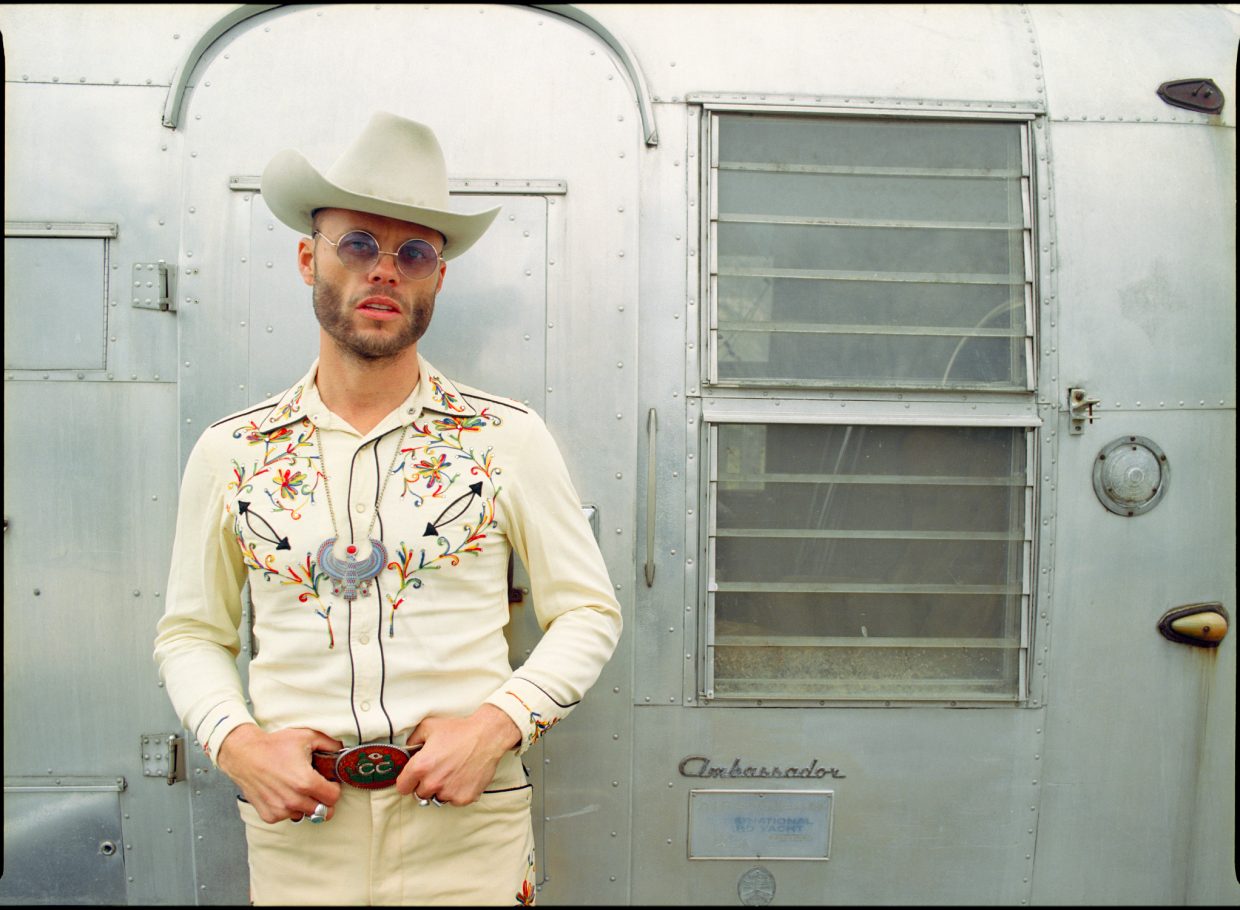

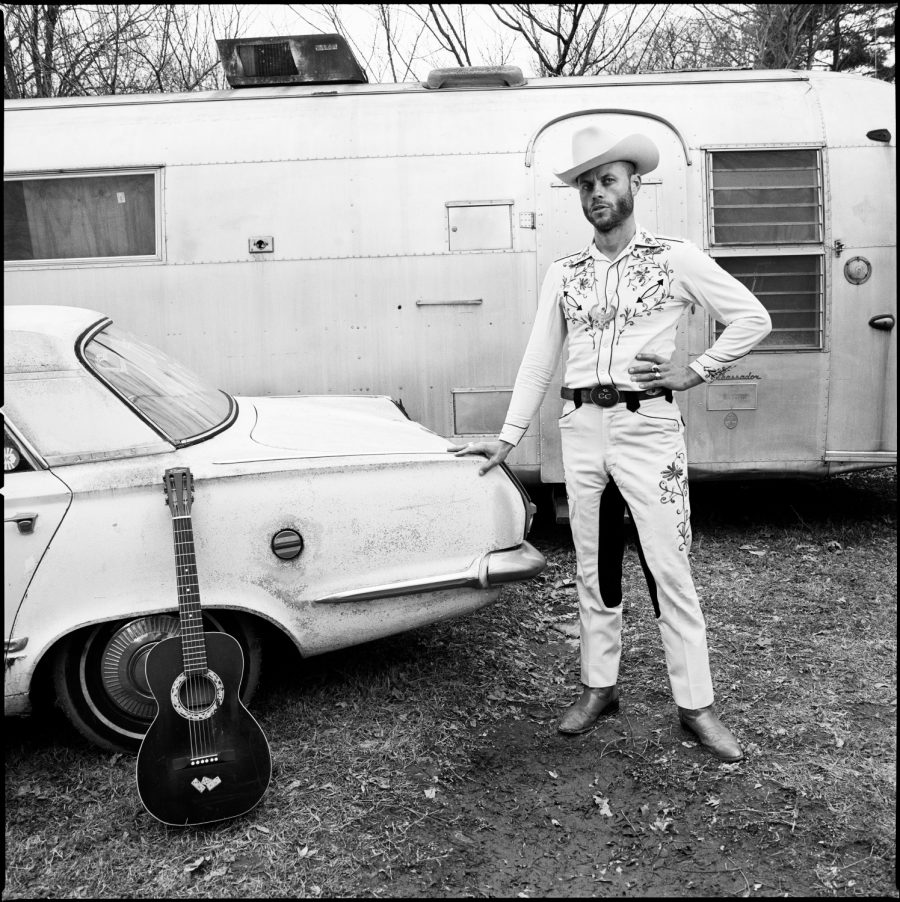

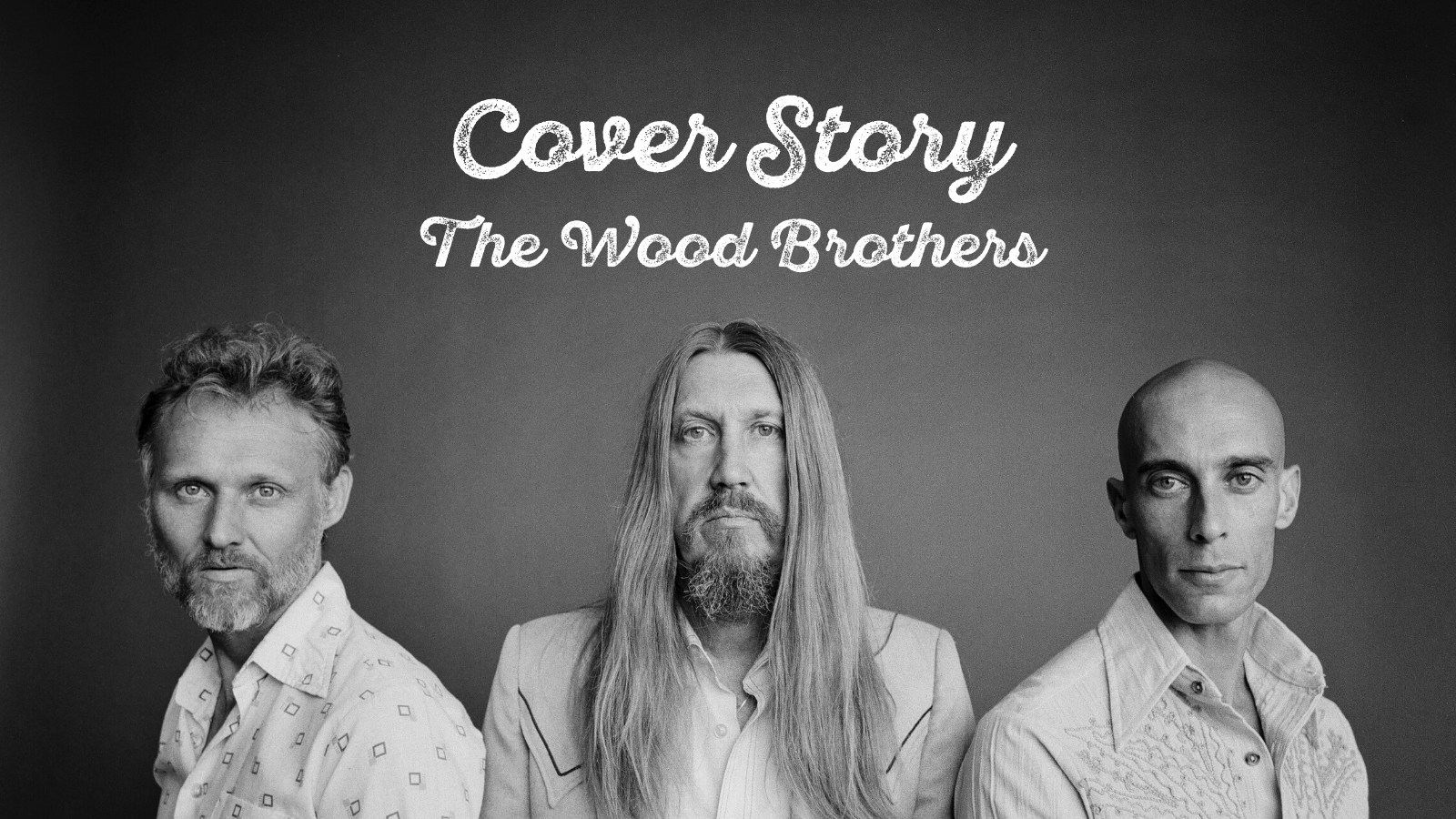

Photos: Alysse Gafkjen