I grew up deep in the hills of the Appalachian Mountains in Eastern Kentucky where, I’m pretty sure, that on a quiet, cool, foggy morning after the rooster crows, you can hear the faint strumming of a mandolin or banjo echoing through the hollers. My home was near the famed Country Music Highway, Route 23, and that set the bar high for me, even at an early age. With local artists such as Patty Loveless, Loretta Lynn, Dwight Yoakum, The Judds, Ricky Skaggs and Keith Whitley and songwriters like Larry Cordle, later joined by artists like Chris Stapleton and Tyler Childers, there was always an incredible standard of music and songwriting to strive for. It also encouraged me, because if it could happen for their hillbilly asses, then why not mine?

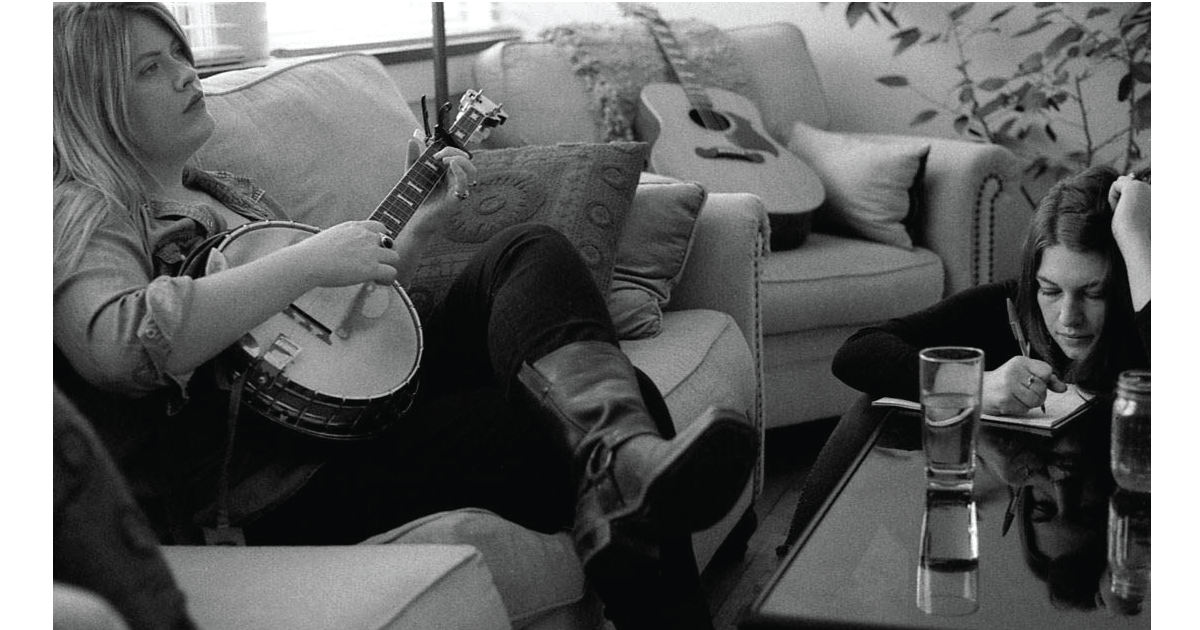

Kentucky Bluegrassed is a sister record to my sophomore album produced by Sturgill Simpson and David Ferguson. My husband Adam Chaffins and I, along with an incredible crew of pickers (Rob Ikes, Stuart Duncan, Seth Taylor, Matt Menefee, Dominick Leslie) reimagined five songs from the Kentucky Blue album and added three new songs, to boot. Although Kentucky Blue and Kentucky Bluegrassed are kin, they have their own unique personalities and can stand separately as two distinct independent projects. Kentucky Bluegrassed is exactly what the title implies. It is “grassed” versions of some songs from the Kentucky Blue record.

I’ve never claimed to be a grasser, but I’ve always loved the genre. A lot of my favorite country acts growing up either started with bluegrass music and went to country or started in country music and went to bluegrass. My favorite country artists always drew from bluegrass inspiration and instrumentation and blurred the lines of country and bluegrass music. This Mixtape is comprised of songs that I grew up listening to and that inspired the sounds and writing on Kentucky Bluegrassed. – Brit Taylor

“Pretty Little Miss” – Patty Loveless

(Songwriters: Traditional, additional lyrics by Emory Gordy Jr. and Patty Loveless)

It’s 2006 in Prestonsburg, Kentucky, and I’m standing side stage at the Mountain Arts Center waiting for my cue to prance out on stage in an old, ugly vintage dress, silly hat, and no shoes. I always picked Patty songs to sing, whether they were bluegrass or country. I loved them all. During this particular summer show season of the Kentucky Opry Junior Pros, I chose to sing Patty Loveless’ “Pretty Little Miss.” There’s something raw and painfully beautiful about the way that Patty Loveless sings. She feels every note and you feel it with her.

Patty is a wonderful songwriter and a hell of a song hound. She surely knew how to sniff good songs out, and Patty and Emory (husband/producer) knew exactly what to do with them when they found them. Whether she writes the song or finds a great song to sing, she knows how to empathize with the song’s character and you can hear it. Unlike some of her more heart-wrenching songs (like my personal favorite, “You Don’t Even Know Who I Am,” written by Gretchen Peters), “Pretty Little Miss” is funny and fun, plus she wrote it! And she sings the shit out of it. Patty Loveless, like Dolly Parton, knows how to get into character and have fun.

“Busted” – Patty Loveless (Songwriter: Harlan Howard)

Written in 1962 by one of my favorite songwriters of all time, Harlan Howard, this song has been recorded and re-recorded. From Johnny Cash and the Carter Family to Waylon Jennings to Ray Charles and more, this song has been done again and again for good reason. In 2009, my queen Patty Loveless comes along and grasses the hell out of it. Each interpretation of this song is different from the last in pretty drastic ways. That’s one of the things I love about music and production. Music is like water, it can literally fit into whatever mold you want to pour it into. You just have to have some imagination. It’s songs like this that inspired me to write and record my song, “Rich Little Girls.” And it is artists like Patty Loveless and producers like her husband Emory Gordy who inspire me to not be afraid to reimagine a song completely different from its original presentation.

“Truth No. 2” – The Chicks (Songwriter: Patty Griffin)

This entire album is an inspiration for Kentucky Bluegrassed. The songwriting is impeccable as are the production and the playing. The album is full of incredible songs by writers like Darrell Scott, Tim O’Brien, Marty Stuart, Patty Griffin, and others. The tracks could have easily been recorded on a Chicks traditional country record, but I love that they decided to do them this way. I love the melody of this particular song and the extended intro with the fiddle hook. I also love the space in this song. They didn’t fill every “hole” with a lick. They let the song breathe. These are definitely concepts we were mindful of when recording Kentucky Bluegrassed. Where can we let it breathe? What’s the signature lick here and who’s playing it? Heavy on the dobro and fiddle, please.

“I’m Gone” – Dolly Parton (Songwriter: Dolly Parton)

No one can tell a story quite like Dolly. This whole record – Halos & Horns – is a lesson in storytelling. Dolly is always an inspiration. Her ability to connect with her audience through her lyrics, honest stories, and light-heartedness will always be something I strive to do in my own music. This is one of those records that I remember begging my mom to take me to the Walmart in Prestonsburg to buy!

“Big Chance” – Patty Loveless (Songwriters: Emory Gordy Jr. and Patty Loveless)

Lyrics in Patty’s “Big Chance” such as, “Looka here mama, looka here daddy/ This is my true love, we’re gonna get married/ Ain’t a gonna hem-haw, ain’t a gonna tarry/ This is my big chance, we’re gonna get married/” are what inspired me to be confident in my own Appalachian dialect, enough so that I put words like “sworpin’” in my song “Saint Anthony,” regardless of if other people were going to understand it.

“Marry Me” – Dolly Parton (Songwriter: Dolly Parton)

I love the perspectives and simplicity in songwriting on both “Big Chance” by Patty and “Marry Me” by Dolly. The character in Dolly’s song sounds like she might be 13-years-old, hollering to her folks about how she’s gonna run off and marry this new feller! I love that the character sounds so young and also like she just met the boy yesterday. It just lends itself to sweetness and innocence with a light-hearted humor.

I wanted a song about getting married on my bluegrass record simply because my heroes had them on theirs. I love the personality and the very matter-of-fact, bossy lyrics of these songs – and that’s what Adam Wright and I were going for when we wrote my own song, “Married.”

“A Handful of Dust” – Patty Loveless (Songwriter: Tony Arata)

This is another one of those songs that has been recorded again and again by multiple artists and for good reason. It was first recorded by Dolly Parton, Linda Ronstadt, and Emmylou Harris in 1993 and then by Patty Loveless on her 1994 country album. Then she cut it again on Mountain Soul II where she grassed it! Charley Worsham and Lainey Wilson also just released their own version of the song. I honestly couldn’t pick a favorite version if I tried. It’s hard to mess up a song this great. I chose this version for the playlist because it’s grassed and very much an inspiration for grassing several of my own songs.

I realize I have a lot of Patty Loveless songs on this playlist, but that’s because she is honestly who inspired Kentucky Bluegrassed the most. I listened to her songs on repeat growing up and still find myself doing so today. If you have heard Kentucky Bluegrassed and are now listening to these Patty songs from the Mountain Soul records, you will definitely hear some similarities. Rob Ickes, who plays Dobro, and Stuart Duncan, who plays fiddle, who were on both Mountain Soul records also play on my Kentucky Bluegrassed album.

“Don’t Cheat In Our Home Town” – Keith Whitley, Ricky Skaggs

(Songwriters: Ray Pennington and Roy E. Marcum)

Both Ricky Skaggs and Keith Whitley are from near the Country Music Highway in East Kentucky, and you can hear the hillbilly twang in their voices, especially when they’d sing together. This song is wonderful. The harmonies just kill me. If you want a lesson in singing bluegrass harmonies – hell, any harmonies for that matter – this is the record to listen to and learn from. When people tell me they don’t like bluegrass, I always tell them they just haven’t listened to the right records yet. This is one of the first albums I send them to. The self-deprecating lyrics along with the simplicity of the music with its quirky upbeat instrumentation might seem to be a contradictory songwriting and production combo, but that’s just one of the unique and beautiful things about bluegrass music that I love so much.

“Rank Strangers” –The Stanley Brothers (Songwriter: Albert E. Brumley)

My Papaw Hillard Anderson introduced me to bluegrass music when I was just a kid. Truth be told, he liked to put on a Stanley Brothers 8-track tape, drink a little too much Crown Royal and have himself a good cry – or maybe just raise some hell. One of the two. Man, I miss him. When I turned 16 and got my driver’s license, I got us tickets to go see Ralph Stanley at the Mountain Arts Center in Prestonsburg. I picked him up over on Beaver Creek in my little red Mustang and off we went. I think my driving scared him to death. But it was all worth it when we got to see Ralph sing and play. I was able to charm my way backstage because the volunteer door people already knew me from my singing at the Kentucky Opry. I got my Papaw a picture signed by Ralph Stanley himself.

Papaw passed in 2009. I sang to him and strummed my guitar as he died. I wish he could have been here to hear this record more than any record I’ve ever made. But I know he’s got a front seat in Heaven. When I recorded Kentucky Bluegrassed, I took two of my Papaw’s old, scuffed-up Stanley Brothers 8-tracks tapes with me. I set up a little hillbilly altar with the two tapes, some tigers eye, Kentucky agate, clear quartz, and other crystals, a rabbit’s foot, some incense, and a glass of bourbon. I wanted to make sure he knew he was welcome there with us. He was there. I could feel it.

“You’ll Never Leave Harlan Alive” – Patty Loveless (Songwriter: Darrell Scott)

I’ll probably spend the rest of my life trying to write a song this good. Nothing captures where I’m from as much as this one does. It just sounds like East Kentucky. It sounds like the coal mines. It feels like home. The first version of this song that I heard was by Patty Loveless on her first Mountain Soul record. I try to sing it sometimes, but it hits pretty close to home. By the last verse I’m normally in tears. My Papaw was a coal miner, and my husband’s father was a miner, too. Growing up, coal mining was about all there was to do for work around home. So hearing this song just always hits hard.

I hope you enjoy this playlist of tunes that inspired Kentucky Bluegrassed, from the songwriting down to the instrumentation. Songs like these will never grow old or sound dated because they’re too original. They don’t chase any trends of the times. They just are what they are.

Photo Credit: Natia Cinco