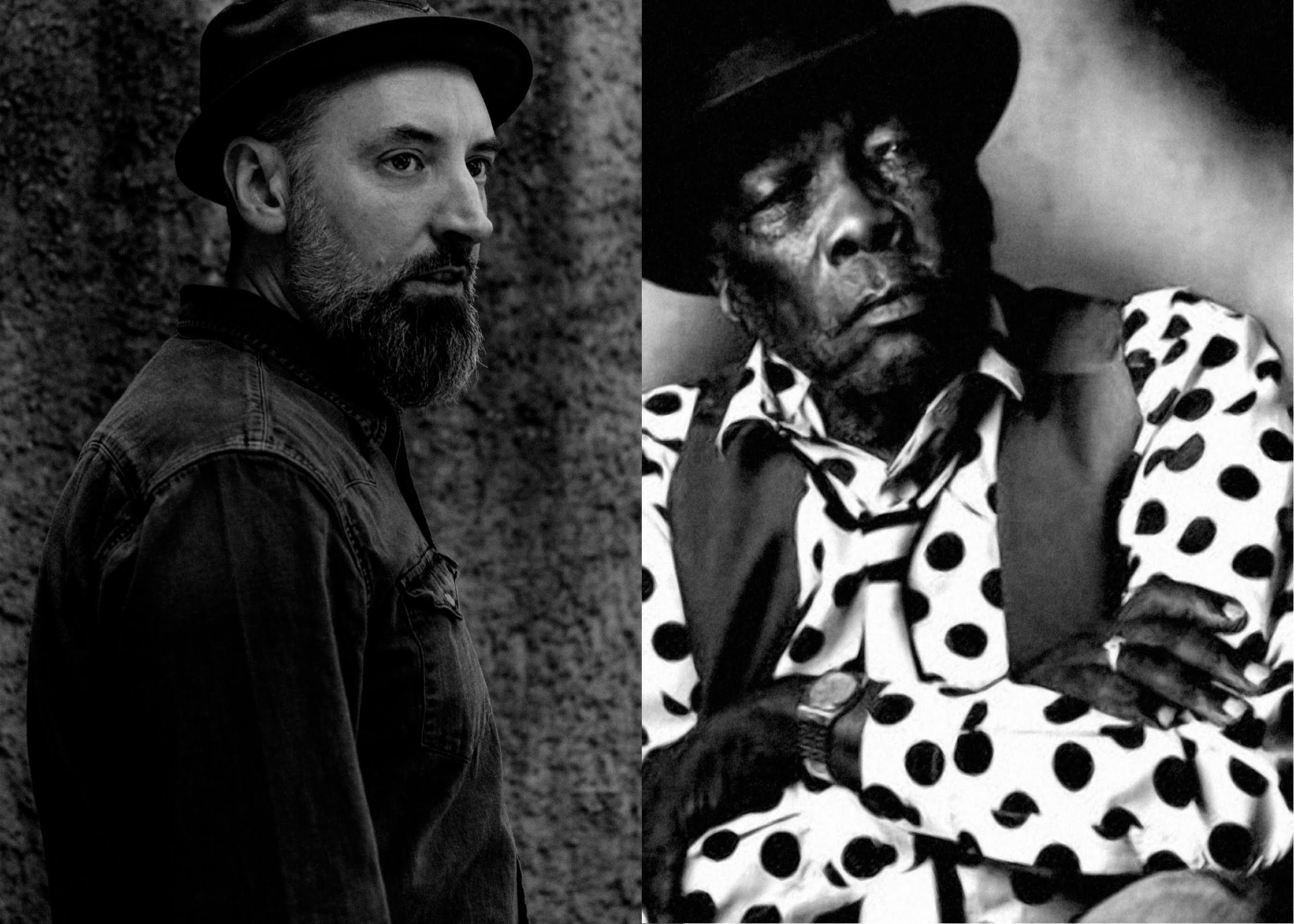

Few would dispute Norman Blake’s place on the Mount Rushmore of acoustic guitarists. He’s spent 50 years defining a flat-picking style adopted by guitarists from Tony Rice to Dave Rawlings. He’s also been a translator of traditional ballads, an influential folk songwriter, and an A-list sideman for the likes of Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and Kris Kristofferson.

But the bullet point version of his career misses what makes him fascinating: a stubborn integrity in his approach to making music — commercial pressures be damned — and a bizarre serendipity that’s led him right into the center of some of folk music’s most important moments of the past half-century. Now he’s capping off his long career with Brushwood (Songs & Stories), an album of beautiful, spare folk that is jarringly modern and political. The songs would sound timeless except that Blake is singing about social media and the Internet — and he often sounds righteously pissed off. It’s hard to explain Norman Blake briefly, but the back-story is worth it.

Born in 1938 on a farm near the Georgia-Alabama line, Blake grew up without electricity, learning songs from a radio jerry-rigged to an old car battery. He dropped out of school at 16 to play in bluegrass bands, made it to the Grand Ole Opry in his early 20s, then was drafted into the Army where he played mandolin in a bluegrass group voted “best band in the Caribbean Command.” Fresh out of the service, he ran into Johnny Cash at a recording session in Chattanooga. Cash asked him if he played the dobro, and 25-year-old Norman said, “Well, yeah.” Cash hired him on the spot.

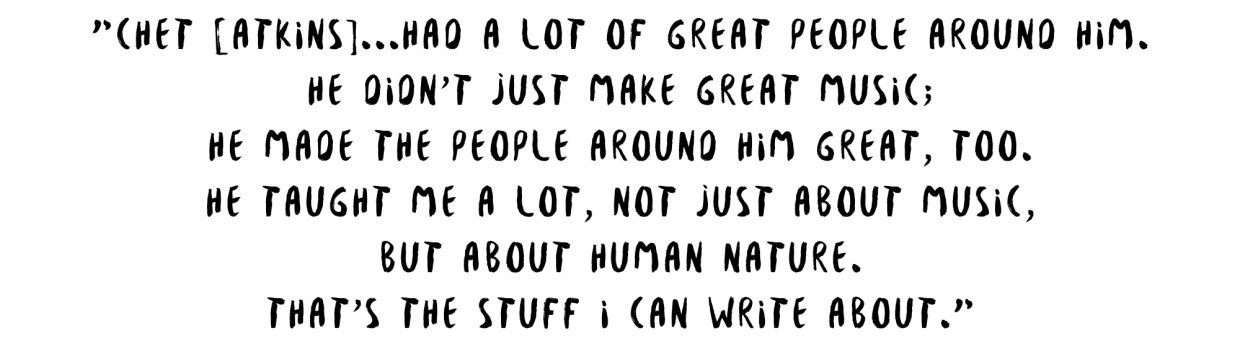

Then, on the seminal, tide-turning albums of the era, he was right there. It’s hard not to notice the Forrest Gump-ian serendipity of it all.

Blake played guitar on Bob Dylan’s Nashville Skyline in 1968, one of the founding albums of country-rock; on John Hartford’s Aereo-Plain in 1971, which marked the beginning of Newgrass; and on the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s Will the Circle Be Unbroken in 1972, which sold approximately as many copies as there were college students in America and introduced old-time country and bluegrass to a longer-haired generation. Thirty years and dozens of albums later, Gillian Welch recommended Blake to producer T Bone Burnett as just the guy to help introduce classic American old-time and folk to another, slightly shorter-haired generation. The O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack, in 2000, won a truckload of Grammys, sold eight million copies, and made enough money for Blake — along with his wife and frequent collaborator, Nancy — to start his retirement from the road.

Now, in true Norman Blake style, he’s adding an unexpected chapter to his idiosyncratic story. The sound of Brushwood (Songs & Stories) is classic Norman and Nancy: guitar and fiddle and voices in harmony. But its content is mostly no-holds-barred fire and brimstone of the modern, progressive variety — as well as some instrumental rags, a couple of train ballads, and a spoken word ghost story. In other words, this 79-year-old master of the craft just put out an album of traditional folk songs about climate change, old time religion, the Koch brothers, train wrecks, the NRA, and Wall Street greed. He predicts it will be his last album, and damn. What a way to tie a bow on it. God bless Norman Blake.

I know, in your music, you’ve never shied away from being political, but it seems like, on this record, there’s a lot more explicitly political songs.

Yeah, I somehow just felt like doing that. I don’t know why. It just came out that way, some of the stuff that I ended up writing.

On some of these songs, like “The Truth Will Stand (When This World’s on Fire),” you’re combining observations about modern life — climate change, the NRA, billionaires running the country — with the spiritual language you’ve been using in traditional songs for a long time. Did that feel like a new thing to do? Or did that come naturally?

Yeah, what I write is just the way it comes out. There’s nothing calculated there. It’s just how I write, yeah.

Well, maybe I’ll go back in time a little bit here. I’ve read that the success of the O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack allowed you and Nancy to stop touring, and you felt that was a welcome relief. I’m wondering what your feelings about performing were earlier in your career. Was there a time when you enjoyed touring, when it was an important part of making music to you? Or did you want to stop earlier?

I had considered stopping earlier, yes — 2007 is when I actually quit touring, quit the road due to age and things like that. You know, just getting tired of the actual road itself at that point. Of course, we did everything on the ground, driving. Just got to where we couldn’t stomach that part of it anymore.

I guess what I’m getting at is, do you think if money hadn’t been a part of the equation, your career would’ve been very different? Would you have traveled less, written more?

Yeah, money was a factor in why we did it. I suppose so, yeah. I had the artistic inclination to want to do it, but the money — certainly making a living … we had a family and everything and had to do something. A lot of times, when we made records through the years, the reason we’d make the record was, we had so much money from the record company — they’d give us x amount of money to make a record — and what we had leftover then that we didn’t spend, we’d usually use that to pay our income tax every year. [Laughs] So we made a record about every year, in some ways, you might say, to pay the income taxes. But it was also artistic at the same time.

So why do you make records now?

More for an artistic sense, I think. The way the world is now, the record business is nothing like it was when we started. It’s a whole different thing. My records have never been huge sellers, so they had to be artistic on one level, I guess. Now they’re more artistic, certainly.

At the end of this record, particularly with “Nameless Photograph” and “Stay Down on the Farm,” I couldn’t help but think it sounded like a goodbye.

It’s trying to be. I think maybe this might be my last one — my last full record that I’ll make. I’ll be 79 years old here in less than two months. So I’m pushing 80 years old. I had a light stroke four years ago, had artery surgery on my neck, and that kind of thing. I never was a great singer, as far as having a great voice, but that’s left my voice pretty gravelly. I just wonder, how long do you inflict yourself on the public as you grow old? [Laughs]

It’s a lot of work to make a record, and I just don’t have the inclination. I have vowed this year — like I said, we quit the road in 2007, but we’ve played a few gigs around home — but this is the first year that I have said that I will not perform this year in public. And I will say this: I may never again perform in public, if possible, unless it’s a money consideration and I have to. I may never perform in public again. That’s what I’m thinking.

Do you still enjoy making music at home?

Oh, I play all the time. I play every day. Oh yeah, yeah. I’ll never quit that. I’m totally committed to playing. But not in public. As you grow older, for me, it takes a lot more practice to keep the playing and the voice and everything to where it’s passable to make records. As far as the performing, that’s also something that’s getting to be too much for me physically. All of the getting ready for it, and all of the traveling that you may have to do, even if it’s around home. I just don’t weather up that good. And I just don’t need the performance pressure, with these medical conditions and things. And I will say this, not to belabor the point, but we — speaking of Nancy and me, both — feel very much that with the climate of the country right now, the political climate and the attitude in the country in general, I don’t feel like I want to entertain some people. I don’t want to go out and put my music before some of them.

That’s interesting. I remember your song from the early 2000s during the Bush administration, “Don’t be Afraid of the Neo-Cons.” I guess the natural follow-up would be, do you think we should be afraid of Trump?

Yeah, I suppose so. But I don’t know that I would go and do that. I feel like there are enough people — obviously, as we saw this past weekend — there are enough people speaking out. I don’t know what the outcome is going to be. The political climate we don’t agree with at all. So we maybe just as well stay home. That’s, like I said, that’s one reason I said I don’t feel like trying to entertain some folks. I don’t feel like putting myself out in front of them when I know that I disagree with them and they disagree with me so radically. The way that people are nowadays, there’s so much weird stuff going on, I feel like some — excuse my French, but I feel like some son of a bitch is liable to shoot us or any of us for being freaks or for playing hillbilly music or singing the wrong song at the wrong time. Somebody is liable to shoot you up there on a big stage in front of a big crowd at a festival. You never know what the hell’s going on now.

Well, a lot of folks have compared the current political turmoil to what happened in the late ’60s. You lived through that, and you were a musician then. So are you optimistic at all about the country now? I think a listener to the new record would hear that you’re not.

Am I optimistic about the country? No, I’m not, in some ways. In other words, considering what’s just happened, how can you be? I understand why a lot of people might have elected him, voted for him, but he took them for a ride. He’s a con man. He conned a lot of these people. And I feel like a lot of them that put him where he is today, how can they look at what he’s doing … it should be painfully obvious, just from the time he got into office, that he’s doing exactly the opposite to what he told them, in a lot of ways. So, no, I’m not optimistic about it. I feel like they really got snookered. Just a minute …

[Nancy’s voice in the background: “Democracy doesn’t come with a guarantee!”]

Nancy says that democracy doesn’t come with a guarantee.

That’s a good reminder.

Yeah, she has some good ideas. She says some good things. In fact, some of the songs on there are inspired by her. She helped write them. I get some good ideas from her!

Speaking of writing, I’m really curious about how you became a songwriter, because it seems like — and you can correct my dates, if I’m slightly off — but you became a professional musician in the late ’50s, early ’60s, but you didn’t make your first solo recording until ’72.

That’s right.

Were you writing songs all along, or were you learning along the way from the great songwriters you were playing with?

No, what singing I did then was mostly just singing harmony parts or something on the chorus in bands, things like that. When I got ready to make that first record — people were saying, “You should make a record” — when it came about that I had the wherewith to do that, with Bruce Kaplan — he was with Rounder at that point, then it became Flying Fish, but it was still Rounder at that time … I thought to myself, “Well, I won’t make a record unless I have some original material.” So I said, “Well I need to write some stuff.” So I started writing then.

Wow. Just like that. For a while after that, you toured pretty hard, and it seems like you didn’t write as much. Is that because you lost interest in it?

Too busy. Too busy driving and performing. And competing in the bluegrass world, trying to survive in the bluegrass world knowing we were playing something that was completely off the beaten track and away from what they were playing. So we just took too much time being professional and performing and driving and getting to gigs and all that. We just didn’t have time to want to be that creative.

What do you mean by competing?

When you sent me and Nancy and James Bryan [The Rising Fawn String Ensemble] out on a bluegrass festival with a fiddle and a cello and a guitar, you know, out there in five-string banjo world, so to speak, we were kind of an oddity. We were fish in a tree.

How did it feel to be so different at those festivals?

Well, we did a lot of musical crusading to survive in that world. And we managed to. But that’s something else — we grew tired of crusading musically over the years.

It seems like you’ve influenced a lot of people over the years that have become very influential in their own right. Might even say you’ve influenced people even more than the folks in strictly five-string banjo world. I’m thinking of Gillian Welch and others. Do you feel like your crusading kind of won in the long run?

Oh, I don’t know. I never knew who I really influenced in the long run. I do relate a lot to Gillian and David. They’re some of my friends, and I respect what they do. They do some great things, and I admire their grit to do it. But I never thought about who I influenced or didn’t. I was never sure about that. I guess I’m never sure of my role in any of it. I just was too busy trying to survive and make a living in the music business, and it was hard enough for any of us. Playing acoustic music has always been a hard way to make a living.

Sure. It seems like, from the outside, at least, that it must’ve taken a lot of backbone to do what you did just because you felt like it’s what you should do, rather than because it was lucrative or because there was a successful niche for it.

We always did what we felt like doing artistically. We played what we knew to play and what we could play and felt like playing. We didn’t really tailor ourselves into any particular thing. We never tried to be commercial in any sense.

Just doing what you felt like you needed to do — is that what it felt like to drop out of school at 16 to become a musician? Was that a popular decision with your family?

I was always pretty well supported by my parents in what I did musically. But they were never quite up for me leaving home at the point that I did starting off on it. I think that worried them a little bit. But they encouraged me, musically, very much in what I did …they were surprised by some of it, you know, that I’d had as much success as I’d had. They didn’t expect that! I think they always considered it as something you couldn’t make a living out of.

After growing up listening to the Grand Ole Opry on the radio in the ’40s, what did it feel like to get up on the Opry stage in your early 20s? To play on that program you grew up on.

Oh, it was a big deal. It was a big deal for us to be on it in any way back in the day. That’s back when it was down at the Ryman. It was the world. It was it. In fact, when I was real young, we couldn’t think past the Opry, hardly. That was the pinnacle, the top of the heap.

I’m wondering about your early guitar education. On the Opry, when you were growing up in the ’40s, there wouldn’t have been many lead acoustic guitar players, right?

No, no, it was not a thing you heard featured very much. It was in the bands. But Sam McGee was playing guitar. He was on there. He was playing solo-type guitar, playing with his brother Kirk. So I heard him.

Sam McGee? I’ve never heard of Sam McGee.

You’ve never heard of Sam McGee!

Well … [Laughs] I’ve heard of a good number of guitar players from back then, I think, but I don’t know of him.

Well, the McGee brothers. Sam and Kirk McGee, the boys from sunny Tennessee, they were billed. They played with Uncle Dave Macon. Sam played a lot with Uncle Dave, made records with him, and then he and his brother Kirk also made records. And then they played with Fiddlin’ Arthur Smith, band called the Dixieliners.

What was his guitar style like?

Sam was a finger-style guitar player, played guitar-banjo and played guitar, kind of a ragtime style. They were extremely good, some of my favorite people. I used to hear them on the Opry when I was a kid.

Did you study his style, learn to play like him?

I never tried to play their stuff that early on. I’m sure I play in that style, that same old finger-style playing — similar songs and stuff. They were very good performers.

Who else was an early influence on your guitar playing?

Mother Maybelle [Carter] was a big influence. Very much so. On those early records of the Carter Family, then later on when I got to know her in Nashville.

What did Doc Watson mean to you when you first heard him?

After I came out of the army in ‘63, I was giving guitar lessons in Chattanooga. One of my students asked me had I ever heard of him, and I said no. I had never heard of Doc. They brought me some records, loaned me some of his records to hear. I was doing mostly finger-playing at that point. I always had played mandolin with a flat pick. I had picked the guitar a little bit that way, too. Then I heard him, and he was getting popular, getting a lot of notice at that point, so I thought to myself, “My goodness.” I thought this was a novelty to play the guitar this way! I had learned from the old way, the thumb and finger style, but then I thought, “Well, I can do this too. This is something I know how to do.” So I started working on it more at that point …

Then, when I got to Nashville, the whole thing opened up. I realized there was a whole word of this going on, so I got right in the middle of it quick as I could. I went through a phase that played both ways. I played with a flat pick part of the time — did that with John Hartford — then I also played alternate thumb and finger style, you know, single string stuff. Ended up finally just pretty well flat-picking.

It’s interesting to think — I mean, a lot of folks listened to the Skillet Lickers back in the ’20s and must’ve known Riley Puckett’s style, and then also were familiar with Maybelle Carter’s melodic guitar playing, but then you said people thought more modern pickers like Doc Watson sounded like a novelty. Why do you think that is? What was the difference?

Well, they just weren’t used to hearing that much played on the guitar with a pick like that. The guitar was more in the bands. When it started becoming a prominent lead instrument, it created a whole new thing. And we never called it flat-picking. That’s a term that came on later. We always referred to a pick like that as a “straight pick.”

Did Doc ever teach you or give you any advice?

Well, I’ve always said I learned from anybody I ever liked. We played gigs with Doc. I’ve had the good fortune to hang out some with him, had some good conversations and things. Got along pretty good.

Compared to learning from folks you’ve played with and folks you listened to and by going on the road, nowadays a lot of young musicians — even folk and bluegrass musicians — are going to conservatory programs to study. Do you think there’s a big difference between those learning styles?

Nowadays, people do everything in a different way. They have to. There’s so much going on. They’ve got access to so much that we didn’t have. I guess any way you can learn it is what you do. We were a lot more rural in our approach. Nowadays, rural life is a lot less involved with it. It’s become more of a fad, in a lot of ways. But they just don’t come from the same world that we did. They didn’t grow up down in the country. A radio to listen at is all we had, and a handful of records on a wind-up Victrola or something. Nowadays, they can access anything that’s out there.

Do you think that access to everything, that lack of common influences, is changing the way people make music? It seems like older generations of musicians always talk about these common touchstones, like listening to the Opry on the family radio or watching the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show …

Yeah, I don’t know. I wouldn’t know. But when I first started hearing music, we just had the Opry on the radio and a few other radio programs — of course, it was live music on the radio, on our battery-powered radio. We didn’t have electricity, when I was a kid, so we had a battery radio, a phonograph, a few records, and whatever you heard people playing around the community. That’s all we had to draw on.

Why did you decide to incorporate storytelling onto this record — I mean, spoken stories?

Just stuff I’d written. I figured, “Well, if I’m not going to make another record, then these things are never going to get heard.” Whether they should or shouldn’t. They were just things I’d written that weren’t a song, so I said, “Well, I’ll put them on there.”

Do you think younger folk musicians have a responsibility to tell it like it is, like you do, to talk about the modern world or politics in their songs?

I don’t think they have a responsibility to, no. They just have to do what they feel like. It’s their own decision. If they feel like that, they should do it … I always felt that I didn’t want to overdo that aspect of things, I mean politically. If I was really trying to entertain people like years ago, out where people would expect me to play the guitar, I didn’t feel like going out and getting too political — just like a lot of performers get too religious on stage. I think it turns people off, if they didn’t go there for that. If it’s a political rally and you want to be political, then that’s a different thing. But just to go out in a general manner to entertain people, I think politics and religion are some things that should be avoided to some degree. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t sing a religious song! We always did. But I mean, you shouldn’t go out and get on the stump, if people aren’t expecting it or didn’t go there to hear that.

So now that you don’t perform live, you feel free from those considerations?

Yeah, I put it on a record. I’ve always said I’ll use a record for any kind of soapbox I decided to get on. In public, I wouldn’t want to play this latest record. If I went out to play, I wouldn’t do that stuff!

Well, let me finish with one more question for you.

Go ahead.

I haven’t really heard anyone sing about social media or the Internet in a folk song before, and it was sort of … well, refreshing, I guess.

[Laughs] Well, thank you.

It strikes me as funny that most young folk musicians seem committed to using their parents’ and grandparents’ vocabulary and, as far as using modern words, you’ve beaten us to it.

Well, I feel like it’s all there, you know. The old stuff’s there and the new stuff’s there and it’s out in the world. It just fell out that way. It was not calculated, it just came out that way.