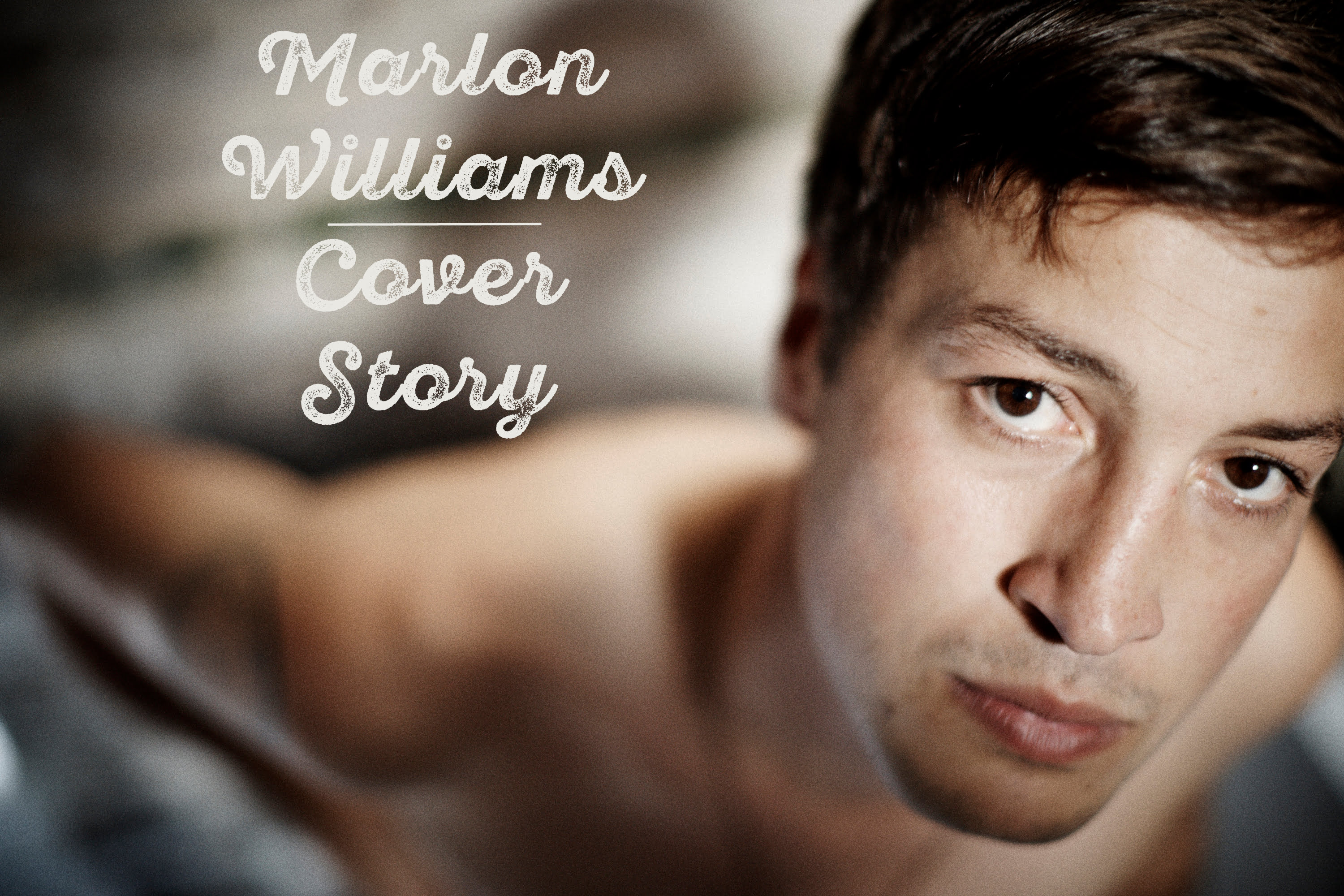

Marlon Williams staked his name on grandiose vocals and an adventurous sound stoked by the Americana fire. When the New Zealand singer/songwriter began touring the States behind his 2016 self-titled debut, his ramped-up “Hello Miss Lonesome” showcased a breathtaking sustain in that it quite literally took Williams a good deal of breath to hold the opening “Hello.” Yet, on his sophomore album, Make Way for Love, he sheds those theatrical moments to pursue a different sound. Williams lets his voice break, searching out quieter moments reflective of his inner anguish, as he worked his way through myriad passions: jealousy, possession, self-loathing, and the one fueling them all, heartbreak.

Heartbreak, as a theme, seems to be the modus operandi for many a singer/songwriter. If they’re not singing about love, they’re singing about its opposite. While Williams wrote his debut through the perspectives of several characters — letting their voices form a barrier to keep his true self private — Make Way for Love takes a different tack. The songs detail his breakup from fellow New Zealand singer/songwriter Aldous Harding. (Interestingly, Harding appears on the penultimate song, “Nobody Gets What They Want Anymore.” The duet, a conversation between former lovers, hangs with a haunting echo of all they’ll never be able to say to one another.) But beyond that overarching subject matter, Williams tackles issues of communication — how seemingly impossible it is to convey an entire truth to another person, let alone oneself.

If Williams was influenced by alt-country and indie folk on his debut, he shows threads of Roy Orbison, Scott Walker, Anohni, and even Jeff Buckley on Make Way for Love. “Can I Call You” begins with an antiquated piano, its keys plunked one by one in heartbeat fashion, before Williams practically pleads the title. One of the album’s standouts, “I Know a Jeweller,” touches on his former sound while nodding at turns to surf rock. With Orbison-like vocals, he demands with a voice oscillating between hope and despair, “Make me a ring for the one who is too afraid to try.” Heartbreak may be old hat for singer/songwriters, but Williams uses it to spin a new thread for his musical development. It is, at once, a man looking around at the wreckage, and a glimpse at a promising musician who’s finally letting his guard down and allowing listeners to get a touch closer.

Your debut involved so many characters and narrators. Besides the heartbreak radiating from the center, why did it feel necessary to peel back those narrative devices and insert yourself more personally this time?

I think the word “necessary” is a very on-the-point description. That’s really how the whole process felt. I didn’t feel I could be so removed this time around, and circumstances were such that I just felt compelled to make a record that was pretty much entirely coming from a personal point of view.

How did you handle the business of confessing and revealing just enough without giving too much of yourself away?

It kind of felt like a crime of passion, you know? I hadn’t really written a song at all in nearly two years and then, in the space of just over three weeks, 15 songs came out. There were ideas that had been floating around in my head for a long time, but there was a fear or reticence about committing them to any sort of reality. It really just happened and I sort of woke up a few weeks later with blood on my hands, and I didn’t know what had happened.

Do you think, if it hadn’t happened that quickly, you might’ve overthought that process more than you let yourself at first?

Yeah, it feels like I sort of blindsided myself. I have always had that relationship with songwriting, where it’s done very frantically and out of fear, really, and I’m left with the results. There’s not a lot of discipline or intentionality going into the way I do it.

I understand that underlying fear, though. You know you have to get it out, but the process can be so overwhelming at times.

Yeah, I don’t listen too closely to myself, so I came out with all these songs, and it wasn’t until right at the end of the process where I realized sort of what I was doing and how personal a body of work it was. I found myself having to choose to make this commitment, this, “Well, I’ve gotten so far with all these songs, is this the right way to do this?” I realized that I had to take the plunge and just commit to it.

It reminds me of the Polar Bear Plunge, where people dive into the icy water so quickly they don’t feel the pain.

That’s the artistic version of that, yeah. [Laughs]

I’m curious if there was any kind of emotional truth you were hoping to unfold over the course of this project, but maybe you weren’t even aware of it until it all came about.

Yeah! I really think it was a means of processing and as real a therapy as anyone ever receives.

Your first album contained such big vocals — both in terms of the volume and also your ability to sustain a note. This is quieter and more introspective for good reason. How did you see your voice serving this project?

I feel like, with this album, I wasn’t writing vocal parts; I wasn’t consciously trying to crack little vocal tricks. All the vocals are serving the song first, so my voice ends up in different and interesting situations that it wouldn’t normally end up in because some of these songs, I guess, represent feelings I’ve never had. “I Didn’t Make a Plan” is just, “This song feels like it wants to be sung down here.” It’s not a part of my personality, but this is what the song wants to do, so it’s what I’ll do.

There are so many styles taking place on this album. What were you listening to ahead of time to shift your mindset away from what you’d recorded in the past?

A lot of stuff. A lot of Scott Walker, obviously. That intensive vocals and tone that’s slightly off and darker than the more obvious Roy Orbison and …Well, obviously Scott Walker is a strange dude. Trying to listen to stuff that really brings my own sense of what I do, of what I’m capable of doing, and how I want to use my voice and present songs. It sort of shifted.

Make Way for Love has been touted as a heartbreak album, but of course any kind of label can be restrictive in a sense. Did you find yourself pushing past those limitations in any way?

The term “heartbreak album” sort of smacks a little bit of sensationalism into it, in a way. But also I’m really curious and really enjoy watching the album squirm under the moniker of “breakup album.” It’s interesting when you give labels to things how you see … I heard someone refer to it as a heartbreak album, and then I listened back to the album myself, and it’s a really interesting re-learning process for me as the album is heard by more and more people.

The song “Nobody Gets What They Want Anymore” is beautifully bleak. Have you reconciled yourself to living with that understanding?

Well, look, that sort of resignation is not eternal nor should it be. It was in the context of the subject matter of the album. I’d sort of come to live with that, I guess. [Laughs]

You can be happily melancholic, as they say.

Yeah, exactly. You can wear sadness well, and it’s fine.

Most of the album is written from a certain perspective, but “Nobody” turns into a dialogue. Why choose to have another character speak on the matter?

I found myself in a unique position of being able to give a voice to … if we’re speaking frankly, there aren’t many breakup albums that are engaged with the subject that the album is about, and kudos to Aldous [Harding] for agreeing to do that. We always had that sort of thread running through our relationship from the get-go, so it didn’t feel that weird to potentially do that.

What was the recording process like?

It was detached and weird. It was one of the last songs we recorded, when we were [recording] in California. I had my parts all done, and then the last thing we needed was her part, but she didn’t record it for another couple of months. She did her part while she was in Cardiff and Wales, and I was in Portland, and we sort of talked it through on the phone. It was a very fitting way to do it.

No kidding, especially considering all the themes of communication that run across the album. To have this significant moment run across time zones and continents …

Exactly, yeah. I would’ve rather we’d done it in person, but it kind of fits.

Speaking of communication, have you thought much about the ongoing struggle to communicate with yourself, and what you’ve learned as a result of this album?

I need some time to think about that one. It’s big.

Save the big ones for the end.

Real big one, yeah! I do feel how I imagine people feel when they’ve been doing a bunch of therapy, where therapy is about picking away the scabs and having a good look at the wounds. I have this weird, manic ecstasy from thinking that you’re confronting these sorts of things. It’s like I’m an alcoholic, and I just want to tell everyone how great AA is. That weird ecstasy that comes from drastic perspective shifts.

I’m just trying to be slow with it and learn to be alone softly and without any pomp and circumstance. I’m having a really interesting and exciting time, where I am starting to feel some sense of individual completeness, which is kind of a new feeling for me.

And a hopeful one, too, I imagine. How do you slow yourself down when you talk about writing an album so quickly? It seems like it’d be tricky to make that momentum shift.

Yeah, it’s tricky, because you make something so quickly and then, by the very nature of what you’re doing, you have to spend so much time talking about it and pouring over it, and I believe you end up inventing the truth afterward. For that reason, I’m either discovering it or inventing it, as I go along. It’s constantly shifting in my hands. You need to be thoughtful and have some degree of slowness and a sense of space and respect for what you’re doing, at that stage.

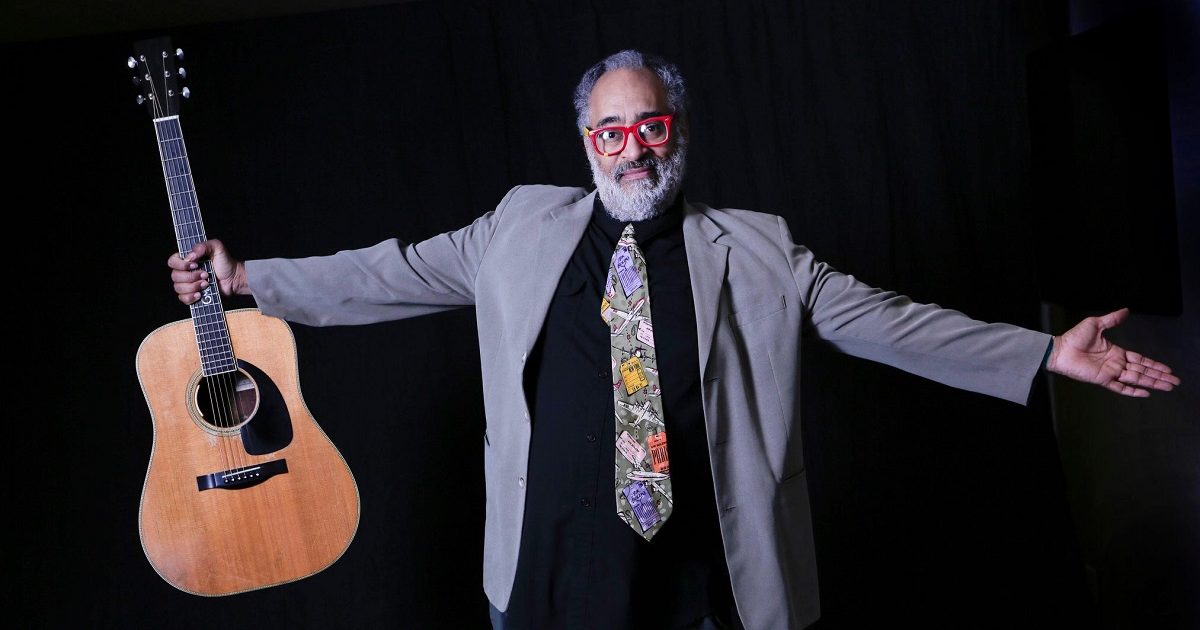

Lastly, what kind of strings do you use on your guitar?

That’s a very functional question after …

I know!

I just use the Martin Retro strings when I can. Actually, the second album I recorded with an acoustic guitar — an old, beat up one — that I found in the studio because I forgot my guitar.

Oh my goodness. Yeah, and I guess you can’t go back for that once you reach California after leaving New Zealand.

I was kind of stuck.

It sounds beautiful on the album, so good find. That’s lucky.

Aww, thanks. Well, it was a shitty guitar, but sometimes shitty guitars are the ones you want.

Photo credit: Steve Gullick