Although it will be showcased for the next two years, the recent grand opening celebration of the “Jerry Garcia: A Bluegrass Journey” exhibition at the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame & Museum will go down as not only a monumental gathering of musical legends, but also an unforgettable moment in time for all involved.

“This exhibit is coinciding at a great moment for bluegrass,” says Carly Smith, museum curator. “[Jerry] funneled so many people to [bluegrass]. And a lot of present day artists — Billy Strings, Molly Tuttle — are incorporating Jerry’s style into what they’re playing.”

Located in downtown Owensboro, Kentucky, along the mighty Ohio River, the Bluegrass Hall of Fame has created an incredibly impressive and intricate ode to Garcia and his undying love of the “high, lonesome sound,” demonstrating how his indelible fingerprint on the genre is still clearly visible in this current high-water mark moment for bluegrass.

Known as one of the finest electric guitarists to ever pick up the six-string instrument, Garcia, who passed in 1995, is eternally known as the de facto leader and musical zeitgeist at the helm of the Grateful Dead. And yet, the foundation of Garcia’s playing and skillset lies in American roots music — folk, blues, and bluegrass.

The exhibit weaves through Garcia’s early years as a folk musician in the 1950s, his lifelong friendship with musician/lyricist Robert Hunter, his time in a slew of acoustic outfits in the 1960s – including Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions (an early footprint of the Dead) – as well as a keen focus on Garcia’s work in Old & In the Way and New Riders of the Purple Sage.

“I cried through the entire [opening weekend] press conference,” Cliff Seltzer, the exhibit’s creative director, says in a humbled tone. “I’ve been trying to keep my composure for this weekend because it’s overwhelming.”

For Seltzer, the journey to the opening weekend has been five years in the making. A well-known former artist manager, Seltzer was touring the museum in 2019 with one of his friends and clients, Vince Herman of Leftover Salmon. With curator Smith guiding the duo through the building, the group started kicking around ideas for what to put in a then-empty gallery portion of the second floor.

“We’ve always talked about a Jerry Garcia exhibit, and it just kind of snowballed from there,” Smith says. “And it was very unexpected how open Jerry’s family was with [helping] us. What I’ve learned over the last two years, really working with them, is that bluegrass was part of [Jerry] — that’s what he was doing when he wasn’t on the road, that’s what he did at home.”

For the better part of the last half-decade, Smith, Seltzer and a small crew of folks roamed America, not only in search of Garcia artifacts to display (instruments, photographs, family heirlooms), but also numerous interviews with some of the biggest names in bluegrass to share in the exhibit — each talking at-length about Garcia’s cosmic lore, larger-than-life legends, and lasting legacy.

“Every genre of music has to morph and change. New people enter the fold and introduce new things,” Seltzer said. “With Billy [Strings], Molly Tuttle, Sierra Ferrell, and others, bluegrass is bigger [now] than it’s ever been — it’s only going to continue to grow.”

Way before the Dead — before any of the melodic chaos and intrinsic beauty of what that band created onstage any given night for its 30-year tenure — there was Garcia himself, simply a huge bluegrass freak who, perhaps someday, would become a member of Bill Monroe & The Blue Grass Boys.

And although Garcia would eventually swerve into the electric sounds of rock and roll and blues, he was never too far from bluegrass. There were always side projects and low-key jam sessions with a bevy of acoustic musicians throughout the early years of the Dead in the 1960s and 1970s.

Most notable of those collaborations was with mandolin virtuoso David Grisman. Through Grisman, Garcia met guitarist Peter Rowan in 1972. A former member of Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys, Rowan found a kindred spirit — in sound and in attitude — with Garcia. The kismet trio would jam often at Garcia’s Stinson Beach, California, home, with Garcia plucking his trusty banjo.

“We started picking every night after supper [at Jerry’s],” Rowan says. “We went through old song books and learned a bunch of material. I remember singing ‘Land of the Navajo’ and looking at Jerry like, ‘This is really weird, isn’t it?’ He goes, ‘Keep going, man.’”

What was birthed from those happenstance pickin’ and grinnin’ sessions became bluegrass super group Old & In the Way. Like a shooting star in the tranquil night sky, the band — featuring Garcia, Rowan, Grisman, bassist John Kahn, and a revolving cast of fiddlers (Richard Greene, John Hartford, Vassar Clements) — would only last the better part of two years (1973-1974).

But, in it remains one of the most important and groundbreaking acts to ever emerge in the bluegrass scene. To note, Old & In the Way’s 1975 self-titled debut album went on to become the bestselling bluegrass album of all-time – until it was dethroned by the O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack released in 2000.

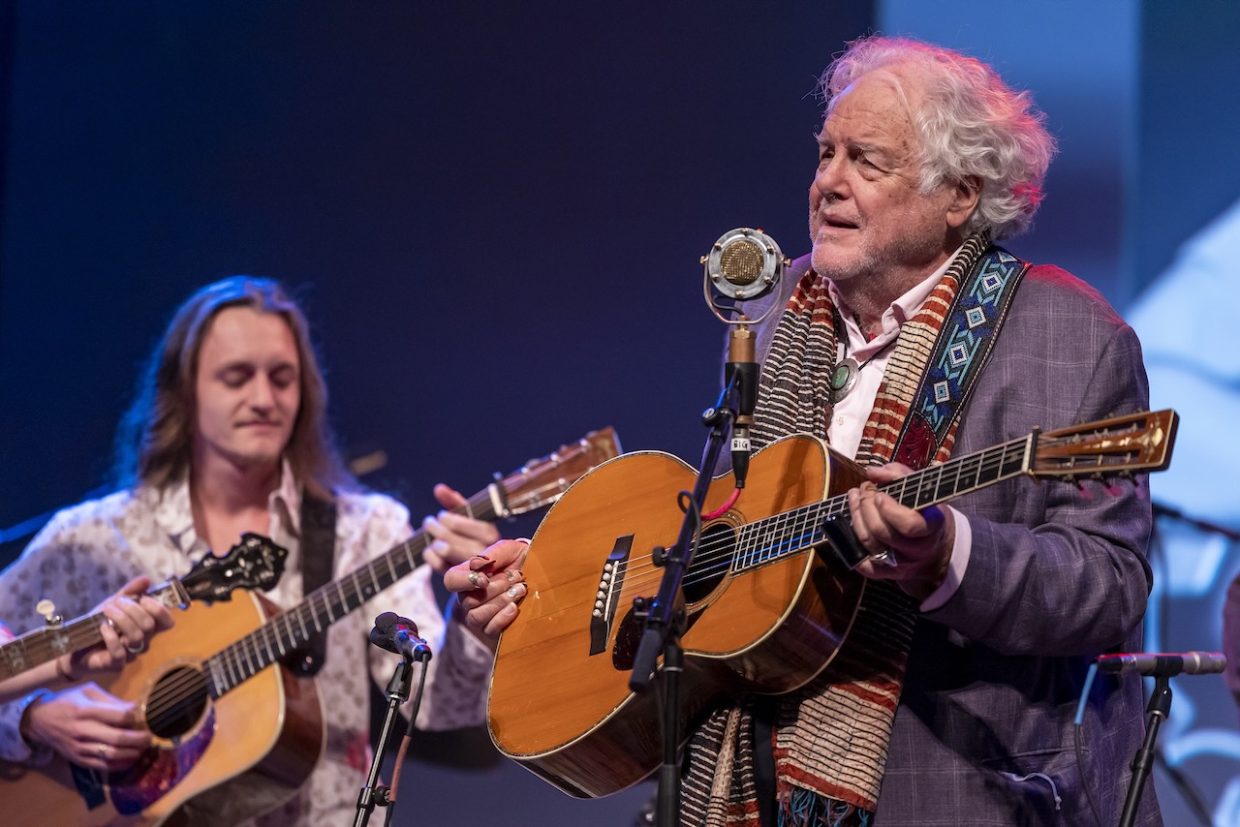

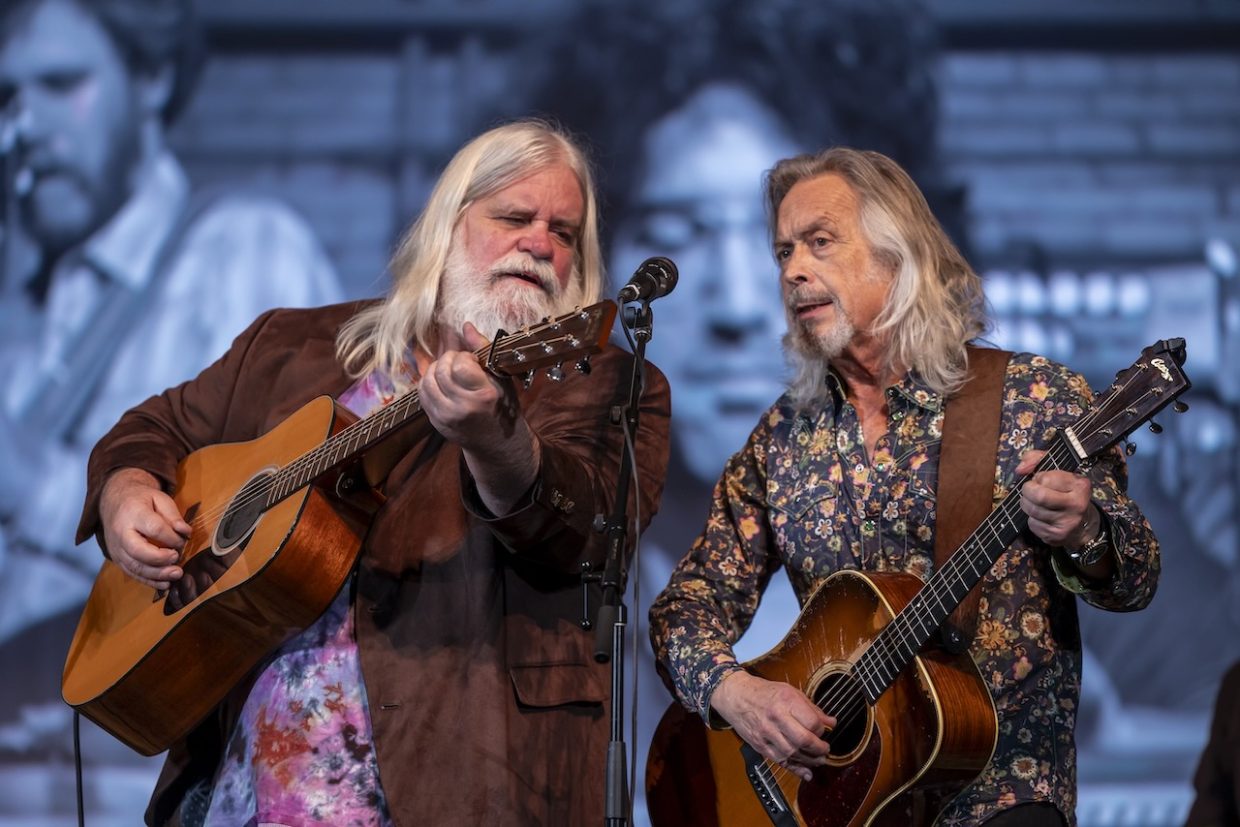

Alongside an onslaught of beautifully touching performances (Leftover Salmon, Maria Muldaur, Jim Lauderdale, Kyle Tuttle, Peter Rowan, Ronnie McCoury, Sam Grisman Project) and poignant gatherings of artists and music lovers throughout the “Jerry Garcia: A Bluegrass Journey” opening weekend, there were also several panels taking place each day at the museum.

Of which, “Garcia: Legend & Lore of a Bluegrass Freak” featured Peter Rowan (Old & In the Way), David Nelson (New Riders of the Purple Sage), Pete Wernick (Hot Rize), Sam Grisman (son of David Grisman) and Eric Thompson (Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions).

“Old & In the Way really helped everything get bigger,” Wernick says. “It was this whole group of material that means so much to all of us in the bluegrass scene — it suddenly became something that people all over the world knew about.”

Below are a few excerpts for that artist panel conversation:

Eric Thompson: I grew up in Palo Alto, California, kind of the nexus point for the folk world in the early ’60s. Joan Baez was from there. The Kingston Trio was from there. I got into the bluegrass guitar in [1961]. [Jerry] ended up there after he got thrown out of the Army. He got into all kinds of folk music and he would just devour a style. [He’d say], “Oh, I’m going to do that,” then two weeks later he’s got a whole repertoire. I was 15 years old and made friends with Jerry right away — it changed my life.

David Nelson: We’d go down to Kepler’s bookstore, which is an old hangout in Palo Alto. There was a section of it where you could get an espresso, sit down at a picnic table, and read a book. And there’s this guy [there]. It’s summer, so he’s got his shirt open and [big] hair. And he’s playing a 12-string guitar. Somebody comes up and says, “That’s Jerry Garcia.” We went over and pitched the idea [of jamming together]. Sure enough, next Tuesday night, we’re waiting and waiting. Then, all of a sudden, here comes the car and there’s Jerry coming up the stairs with a guitar and some friends. It started off a whole [jamming] thing at the Boar’s Head [Tavern], which just went on for months and years maybe. [Jerry] was interested in bluegrass banjo and I was interested in bluegrass guitar. I got me a banjo. Jerry said, “Oh, man, borrow my guitar. Can I borrow this banjo?” He happened to have a 1940 Martin D-18 [guitar].

Thompson: [Jerry] brought some openness to the approach [of bluegrass music]. I know [so] many people, who are mostly not bluegrass musicians, who found out about [bluegrass] because of Old & In the Way. It was open and expressive and, at the same time, paid respect to what came before. It was this new, intelligent thing. And intelligence is what Garcia brought to the music, [as well as] imagination, articulation.

Photo Credit: All photos by Chris Stegner and Emma McCoury, as indicated. Courtesy of the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame & Museum.