Growing up near the Sequoia forests of Northern California, Avi Kaplan gravitated toward the low-key albums by John Denver, Bill Withers, and Simon & Garfunkel in his parents’ CD collection. But in time, the term “low-key” took on a whole new meaning as his baritone voice dropped dramatically upon starting high school. Suddenly possessing a clear, thundering bass range, Kaplan discovered a newfound confidence and rare vocal ability that ultimately led him away from the dream of becoming a choral director to joining the a cappella group Pentatonix.

After six years as a member of that Grammy Award-winning group, Kaplan parted ways with Pentatonix in 2017 and essentially went off the grid for a year. Now living in a cabin in the woods outside of Nashville, he is ready to reconnect to his roots — as he did on his new album, I’ll Get By. With a speaking voice that’s as resonant as you’d expect, Kaplan caught up with BGS by phone.

BGS: I’ve read that you had an early interest in folk music, so I was curious to know if you’d consider this is a full-circle moment, coming back to the music that you grew up loving?

AK: Oh yeah, absolutely. I grew up listening to it and it’s always the music that I’ve listened to throughout my life. And it’s always the music that I’ve written as well. I had a departure when I went and did the Pentatonix thing, but it definitely is a full-circle thing. It’s really surreal for me.

You released “Change on the Rise” about a year ago and it sent you on the path to this record. Why did you choose that song to usher in this stage of your career?

In the past I’ve written a lot of songs that are softer and maybe on the prettier side. A little fire, a little less power, and more about the soft, serene beauty of folk music. I really wanted to come back with something that just had a little more fire in it, because it was really reflective of where I was in my life. I felt like I really got my fire back. I didn’t want to come back with something people had already heard from me. Even then, people hadn’t heard much from me in general, when it came to a solo voice, or my voice out of its lower register. So I wanted to come back strong.

What was on your mind when you wrote “I’ll Get By”? That seems like an anthem of this record.

Thanks, man. Whenever I write a song, I don’t listen to it for a while. Then I come back and listen to it again so I can hear it on fresh ears, without the critical ear. When you’re in the writing situation, you’re criticizing everything you’re doing, so I had to get myself out of that. And when I listened to it again, I got emotional. It was something that really felt special to me. It felt really strong to me. It felt like it was conveying exactly what I was going through at that time, and hopefully something that would help other people get through the same type of thing.

On another song, “Chains,” there’s a lyrical reference to needing peace, and phrases similar to that. Were you needing peace and quiet to keep on going?

Oh yeah, absolutely. I was living in L.A. for about seven years and I’m just not a city guy in general. But when I wasn’t in L.A., I was touring non-stop. I was always going, so I really feel like I lost myself and I lost touch with the things that I loved the most – hanging out with my family, being in nature, all that stuff. … It was about a year after I left the group that I really started delving into writing. I wanted to do some healing first, but even through that, I was still healing just from a lot of stuff I was going through. So yeah, absolutely I was in that spot.

What did that healing process look like for you? What were you doing that year?

Well, I left the group and I just took some time to do the time to do the things that I’ve been longing to do. So I camped a bunch. I moved out of L.A. and moved into a cabin in Tennessee. But before that, I went back out to the Sequoias, where I’m from, and did a camping trip there. I did a lot of time in the Eastern Sierras and the Mojave Desert, and up in the mountain lakes.

I also went to Holland. I went to Germany and did a bunch of nature stuff. Then I went to Israel and I went hiking out there as well. So, I kind of went all over and just got away from everything as much as I possibly could. I just sought out to heal and find myself again, and just do work on myself. It was really important at that time. It was something that I needed more than I even knew.

Why did Tennessee become the place you ultimately settled?

I knew that I wanted to do music still. And really Nashville is the only music city where you can drive like 15 minutes outside the city and be in the country. And that’s where I wanted to be. That was a huge reason and also my sister lives out here. Also, with the music that I’m doing, I would say it’s more of a hub than I would say L.A. or New York anyway.

So, all signs pointed that way. I never had a doubt in my mind either. It was like, “OK, now it’s time for me to move out to Tennessee. I need to get a cabin out there and be in the forest.” It was all very clear to me what I needed to do. I didn’t exactly know how I was going to get into a place where I was good again, but I knew that’s where I needed to go to do it.

You mentioned earlier that you’re singing in a different part of your range on this record. But not a lot of people can sing as low as you. When did you realize you can do something that very few people can do?

It was my freshman year of high school. I joined the choir when I was in eighth grade but I was a baritone back then. And over that summer between eighth grade and freshman year, my voice changed big time. So I remember coming to the choir room and my choral director was extremely excited to hear my voice because it’s hard to find basses and that’s very much needed in choir. So he was a huge inspiration for me and a huge advocate for me. He helped me realize how different it was and how I could utilize it. I owe a lot to him, definitely.

It sounds like music education in your school is a cornerstone of your development.

That’s huge for me. Now I run a summer camp for high schoolers based around harmony and a cappella, music, songwriting, and all that, because that was such a huge inspiration to me. It changed the course of my whole life. It’s always been something that’s been important for me. Before I joined the group I was on track to be a choral director. I was also studying opera, but being a choral director was the dream, just because it had such an impact on me.

Was country music an influence for you growing up?

I didn’t listen to actual country, like Garth Brooks and that type of thing, but I loved bluegrass. I loved John Denver. Bluegrass is more of what I listened to when I was younger. And the Sons of the Pioneers, old-school country. There was actually a band in my hometown that was very similar to them called that Sons of the San Joaquin that I listened to a lot.

What was your entrance point into bluegrass?

I really started delving into it when I was a bit older. What’s funny is that I got on the Bluegrass Situation’s YouTube channel and I just went down a rabbit hole. I was blown away by some of the newgrass that was going on, and by some of the old-school. I think one of my favorite videos that you did was the one of Tim O’Brien. That blew me away. I love it so much! I would watch it all the time.

Then I started getting into Hot Rize, and an album with Tim O’Brien with Darrell Scott, and then I got into Elephant Revival, then Mandolin Orange, and I kept going down and down and down. I really delved into it and fell in love with it even more because it felt like my roots. I had grown up with that kind of thing, but I had gotten into more of the contemporary modern folk with Iron & Wine and Bon Iver.

I’m a huge fan of bluegrass and I tell people all the time that bluegrass musicians are world-class musicians. They are truly virtuosic. So unbelievably talented. It’s amazing to hear music that I love with such virtuosic musicians. That is something that is always very inspiring to me – a musician’s musician, someone who is really amazing at their craft. And that is definitely what bluegrass is about.

I wanted to ask about auditioning people for your band. What are you looking for when you pick a band?

I’m always looking for vocals. Harmonies. That’s the most important thing to me. Especially with my music, it’s not the toughest stuff to do, instrumentally speaking. With this album, the drums are actually more complex than I thought they were going to be, but at the end of the day, it’s nothing crazy. The harmonies are really where I’m looking for the strength. Yeah, that’s it – harmonies, 100 percent, all the way.

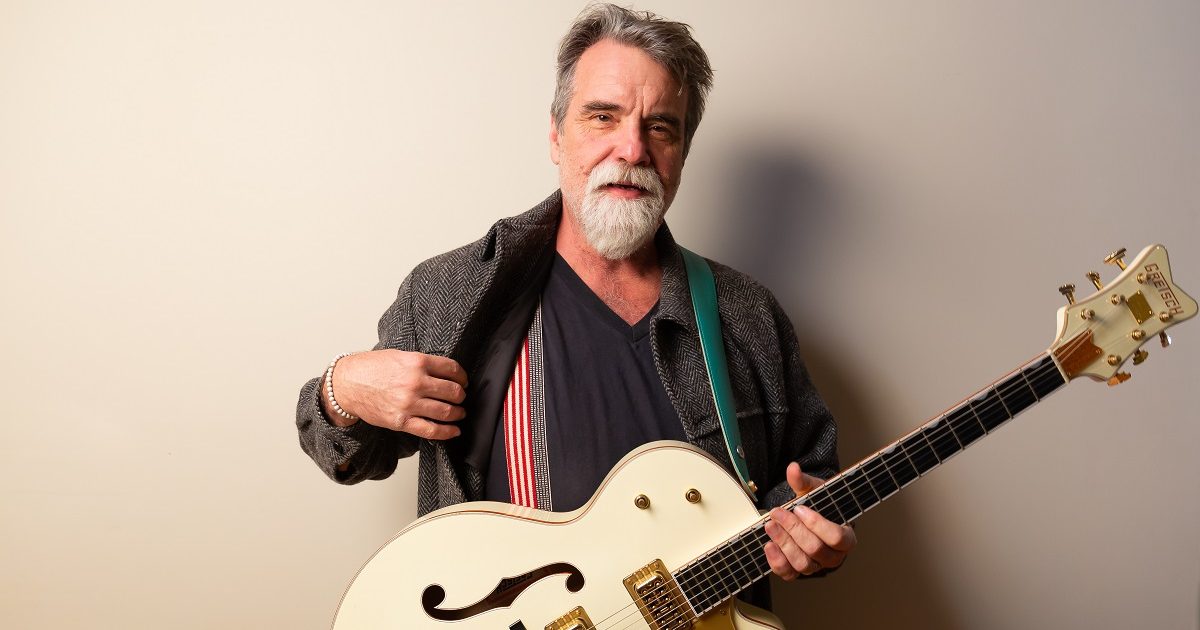

Photo credit: Bree Marie Fish