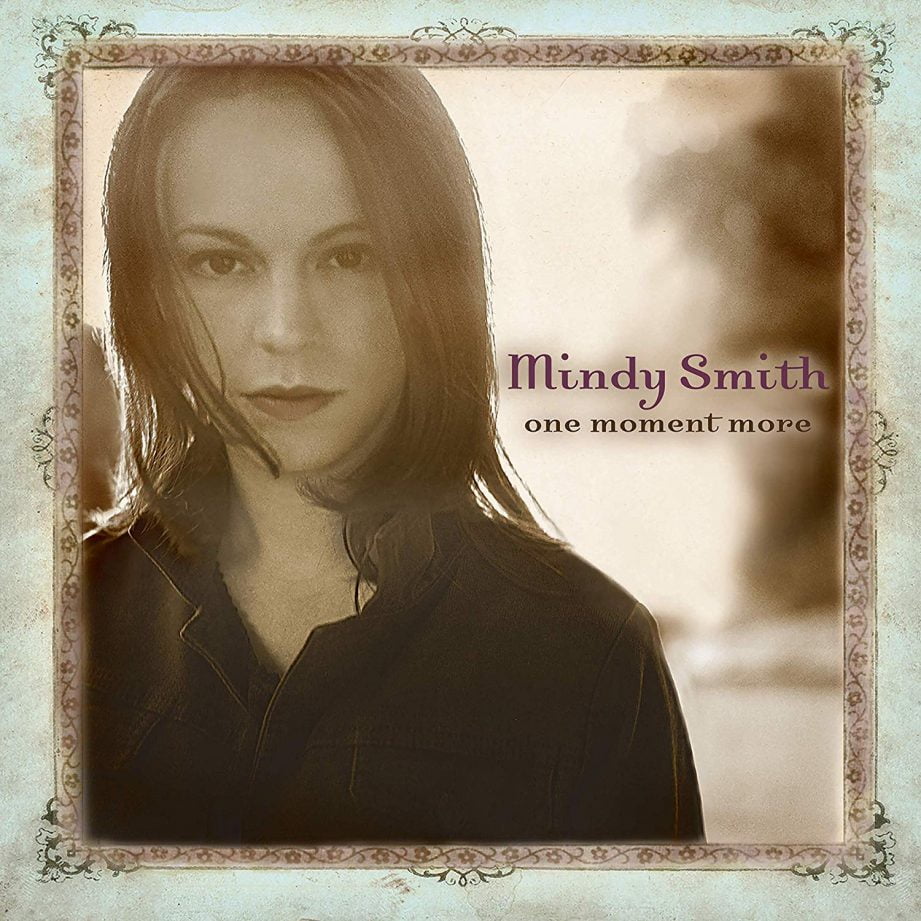

I didn’t want to hear “Come to Jesus” in 2004. As the first single from Mindy Smith’s debut album, One Moment More, it’s a gentle pop hymn, delivered in the voice of a parent comforting a child. “Oh, my baby, when you’re prayin’,” Smith sings, “leave your burden by my door. You have Jesus standing by your bedside to keep you calm, to keep you safe, away from harm.” With a subdued roots accompaniment, Smith follows that child throughout her life, documenting her changing emotional needs as well as her changing relationship with her beloved parent. Her vocals lack twang, but they have a steadiness that seems to arise from the certainty of her faith that mother and child will be united in the next life. “Here in heaven we will wait for you arrival, here in heaven you will understand.”

Smith was writing from experience. In 1991 her mother died of cancer — a loss so cataclysmic that she and her father found it too painful to live in their small Long Island hometown. So they headed south, and Smith enrolled at Cincinnati Bible College (now Cincinnati Christian University), although she has said that decision was motivated by her desire to connect with some of her mother’s old acquaintances. When she released One Moment More thirteen years after her mother’s death, Smith filled it with songs of loss, recovery, and renewal. On “Raggedy Ann” she compares herself to a childhood doll whose seams are fraying and whose stuffing is coming out. On “Angel Doves” she reassures herself that “God is soaring above a world that is running out of love.” Musically, she melds several traditions and styles, from contemporary country to contemporary Christian, into a sound that never announces its ambitions or lets them interfere with her lyrics.

I didn’t want to hear any of it at the time. In 2004 I was still raw from a similar loss, the death of my father in 2002 after a long battle with brain cancer. I watched as one of the sharpest minds gradually lost his ability to speak or communicate in any way. I watched as one of the most generous hearts I’ve ever known lost his ability to recognize his sons. A church deacon and a small-town lawyer, he died just a few short months before the birth of his first grandchild and namesake, which seemed too cruel for me to comprehend. It shook me to my core, and I struggled to reconcile the God I had heard about in my small-town Southern Baptist church with the God who would strike down a good, humble man like my father. It felt like there was too much chance and chaos in the world for it to be overseen by a loving God, and I admit I grew angry and resentful.

Even two years later, the consolations that Smith sings about in “Come to Jesus” — namely, the promise that we will meet our loved ones in heaven — sounded cheap. I was tired of empty reassurances designed to rush someone through his grief, to dam up those messy emotions so others wouldn’t feel uncomfortable. I was sick of having people clasp my shoulder sympathetically to tell me that everything happens for a reason. The idea that we could not possibly understand anything in this life, that we must wait until the next one to get any satisfactory answers, hit my ears with a vulgar dissonance. Ungenerous to all others in my confusion, I rejected what I thought were easy excuses and nursed my own angers and sadness. It felt righteous, in a peculiar way, and honest.

“Come to Jesus” is fifteen years old in 2019, and I am fifteen years older. Now when I hear the song, I listen with very different ears. I listen as someone whose life and livelihood involve absorbing all kinds of music constantly, which means that I hopefully have a better sense of Smith inhabiting and innovating these different genres. More crucially, I listen as someone who has grown spiritually and emotionally, who has further processed the tragedy of my father’s death, who has shed so much of that anger that once seemed so essential to survival. I can hear Smith’s song not as a litany of spiritual excuses, but as an expression of someone still grieving, still trying to work through the mayhem of grief in the hope that she might locate some essential truth of life. Her truth is different from mine, but it sounds like she had something healthier than anger to sustain her. And I can be moved by her song now in a way I couldn’t when I was younger.

So it was only in the last few weeks that I finally listened to One Moment More in its entirety and made it to the title track, which closes the album. That might have been too much for my 15-years-ago self to hear. It’s a song about leavetaking, general enough that it could be sung to a lover or a friend or anyone whose departure would upend someone else’s life. But we know it’s not that. We know that is song is about her mother, which makes the chorus sound even more desperate: “Oh, please don’t go,” Smith sings, that faithful steadiness having left her voice. “Let me have you just one moment more.” There is no poetry in that lyric, which only makes her pleading more powerful. It sounds more direct, more desperate, the emotional need stronger than pen and paper could hold.

The composure Smith shows on “Come to Jesus” has eroded into uncertainty. “Tell me that one day you’ll be returning, and maybe, maybe I’ll believe.” It’s that extra “maybe” that sells the sentiment, that conveys her struggle to maintain her faith. Ultimately, the arc of One Moment More veers from certainty to doubt, which seems unusual. Most albums, especially Christian or country albums from this era, would rather end on a note of certitude and firm belief, because the story of overcoming tragedy is attractive and reassuring. But Smith knows you never truly recover from grief. It grips and marks you for the rest of your life. We will mourn our parents until we die, and at this point in my life, that idea is inexplicably comforting.

Photo credit: Fairlight Hubbard