The O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack, which was just starting to pick up momentum twenty years ago this winter, was both a forethought and an afterthought. The Coen Brothers had an idea for a film and even a title borrowed from Preston Sturges’ 1940 comedy, Sullivan’s Travels, but no screenplay. They commissioned T Bone Burnett to assemble a sprawling playlist of old-time music for them to use as writing prompts — original recordings from the first half of the twentieth century as well as new recordings of old songs. He gathered some of the finest vocalists and players, including Emmylou Harris, Gillian Welch, Alison Krauss, and members of Union Station, as well as Norman Blake, Sam Bush, and John Hartford. In various combinations they produced around sixty tracks covering hillbilly plaints, gospel numbers, Protestant hymns, children’s songs, labor songs, even prison songs.

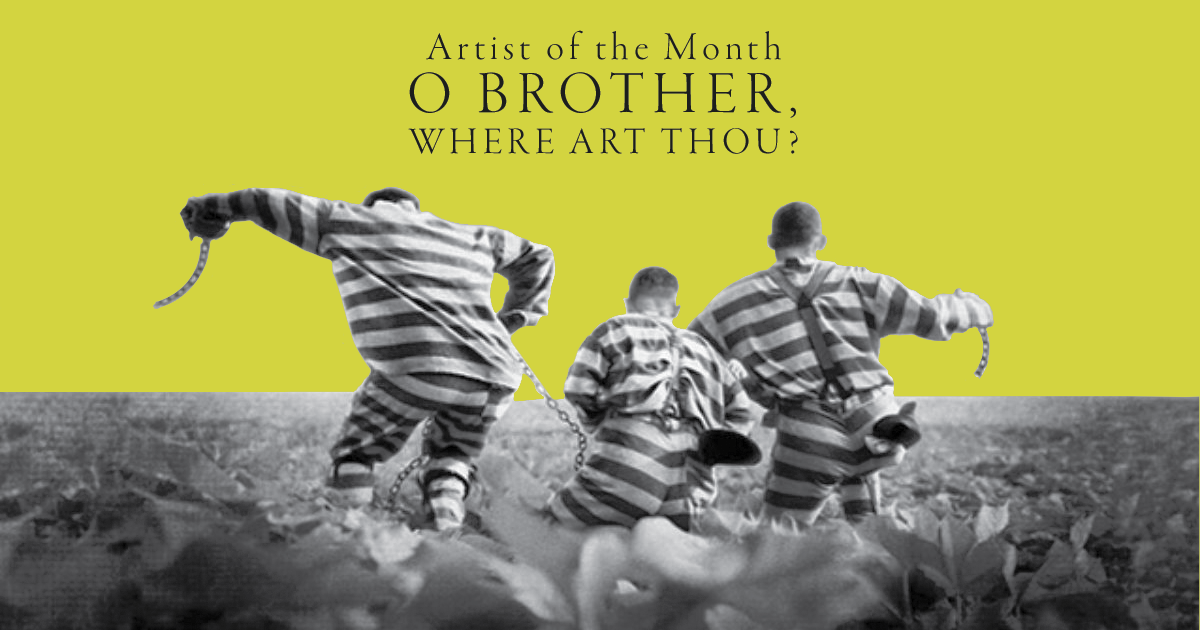

From that pool the Coens selected a handful of tracks that served as the skeleton for their screenplay, which became a Deep South retelling of The Odyssey. As three yokel chain-gang fugitives wander the backwoods and cotton fields and gravel roads of Depression-era Mississippi, they inadvertently become country stars thanks to a hasty version of “Man of Constant Sorrow,” originally recorded in 1917 by Dick Burnett and re-recorded for the film by Dan Tyminski. Along the way they encounter a parade of white-clad Christians singing “Down to the River to Pray,” a blues singer who regales them with a campfire rendition of Skip James’ “Hard Time Killing Floor,” and a KKK klavern performing a Busby Berkley routine in white sheets and hoods.

Whittled down to eighteen tracks, the soundtrack hit stores just a few weeks before the film, and it seemed designed to stand alone as an upscale release. As Luke Lewis, formerly chairman/CEO of Universal Nashville, told Billboard in 2015: “When we were putting it together, a bunch of us said, ‘This is probably going to be a coffee table kind of a CD, where people will leave it around and be proud to have it.’ That turned out to be pretty much true… A lot of people that don’t buy records at all, or buy one a year, bought that record.”

Still, no one figured it would sell any more copies than your typical soundtrack, and certainly no one predicted it would so completely eclipse the film. Its success has been astounding: It has sold nearly 9 million copies, hung around the upper reaches of the Billboard Top 200 for several years, won the Grammy for Album of the Year (beating out Bob Dylan and Outkast, among others), spun off a sequel, inspired a series of tours and live albums, and redefined a massive market for traditional music in America.

Twenty years later, the gulf separating film and soundtrack remains remarkably wide. The former is glib to the point of nihilism, as though every line of dialogue and every camera angle is surrounded by quote marks. The soundtrack, by contrast, is sincere to the point of evangelism, as though these old songs were pieces of secular scripture. The music plays everything straight, while the film can’t keep a straight face. The soundtrack became a phenomenon, while the film sits in the lower tiers of its auteurs’ sprawling catalog.

Both are products of a very particular time: They were released during that short window between two defining events — the hand-wringing spectacle of Y2K and the horrific televised tragedy of 9/11. With the benefit of twenty years’ hindsight, they represent a pop-cultural pivot from the irony that defined the 1990s and much of the Coens’ output to the “New Sincerity” that defined the 2000s.

Why did this niche soundtrack become such a massive hit? Some have credited the popularity of O Brother to fin de siècle jitters and a desire to return to a rosier, more comfortable American past (never mind that the past, especially the 1930s, was never rosy or comfortable). Others have chalked it up to a rejection of the late ’90s pop music excess embodied by Britney Spears and the Backstreet Boys.

Perhaps the best reason for its success is also the most obvious: This is a good album, and an accessible one. It’s a well-curated tour through old-time music, a sampler of rural American traditions that serves as a primer on the subject without sounding like a textbook. All of these different styles are presented with an eloquence that is homespun yet modern: a balance that highlights rather than dampens their charms.

Burnett puts such an emphasis on the human voice that even the instrumental tracks sound a cappella. He wants you to hear the exquisite grain in the voices of Emmylou Harris, Gillian Welch, and Alison Krauss on “Didn’t Leave Nobody But the Baby” as well as the weight pressing on Chris Thomas King as he moans through “Hard Time Killing Floor.” Curiously, Dr. Ralph Stanley had to convince the producer to let him sing “Oh Death” without banjo, which was absolutely the right call. His voice is high and keening, a serious a death, shaken by the very subject he’s singing about.

If there’s a breakout song on O Brother — something resembling a hit — it was this very intense performance, which remains one of the finest renditions of this very odd and oft-covered song. Stanley was 73 years old when the album was released, had been playing since 1946, and was already celebrated as one of the fathers of bluegrass, but O Brother gave his career a considerable boost, introducing him to a significantly wider audience. (That said, it always struck me as deeply disrespectful that the Coens have a Klansman lip-synching Stanley’s performance in the film, as though they feared the words might actually mean something.)

Stanley performed the song a cappella at the 2002 Grammys — imagine anything a cappella at such a glitz-bound ceremony — not long before the soundtrack won Album of the Year. It might have been the climax of the soundtrack’s shelf life, but it kept selling and kept selling. It created an instant audience for old-time music, and upstart string-bands found themselves with readymade audiences, many of them shouting “Man of Constant Sorrow” the way they once might have yelled “Free Bird!” Every artist on the album got a boost, especially Alison Krauss & Union Station, who crossed over from bluegrass to pop and launched a series of hit records with the aptly titled New Favorite in August 2001. Similarly, Welch, Harris, and even Stanley enjoyed boosts in album and ticket sales in the wake of O Brother.

As with any sweeping change, there are new opportunities as well as new losses. The alt-country acts of the 1990s had already lost much of their luster, but roots suddenly had no room for punk anymore. Gone were the dark, twangy experiments like Daniel Lanois’s Americana trilogy — Harris’ Wrecking Ball in 1996, followed by Bob Dylan’s Time Out of Mind the next year and Willie Nelson’s Teatro the year after that. All three proved that roots music could accommodate new sounds, that it could look to the future without completely letting go of the past, and all three stand among the best entries in their artists’ remarkable catalogs.

But O Brother seemed to wipe most of those new avenues away, turning roots music into something largely acoustic, uniform, polite, conservative — beholden to the past and largely dismissive of the present. Watching certain acts riding that wave was like watching Civil War reenactors march on a makeshift battlefield, and ten years later groups like Mumford & Sons and the Lumineers were using roots music to sell arena-size sentiments.

Another aspect of old-time lost in the O Brother wave: politics. Previous folk revivals had a populist bent, extolling the music as the sound of the people and as an expression of a specifically American community. Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger were branded subversives and communists, while Dylan and his early ‘60s cohort found radical possibilities in Harry Smith’s legendary Anthology of American Folk Music. But no one on O Brother is in any danger of being branded a pinko. The film itself nods to issues of race and class, but without really commenting on them in any serious or specific way. The soundtrack, by contrast, foregrounds songs about yearning, about breaking free of turmoil and hardship to find peace and contentment. Often that can be humorous, as on Harry McClintock’s fantastical “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” but more often it’s poignant, as on Krauss and Welch’s “I’ll Fly Away.” It’s a collection more concerned with needs of the spirit than of the flesh, so any earthly implications are largely ignored.

The roots market that sprang up in the soundtrack’s wake was consequently blanched of anything resembling social commentary, despite there being so much to comment on. That wave of bands might have provided a counterpart to the entrenched political conservatism that defined mainstream country music of the early 2000s, but instead it offered merely escapism.

A few artists did manage to question this rosy thinking about the past, in particular the Carolina Chocolate Drops. They traced strains of Black influence, craft, and contribution to old-time music, which is generally considered to be white, and therefore expanded its historical scope and current impact. As players, however, they injected their songs with no small amount of joy, as though taking great delight in what these old forms allowed them to express. The group’s three primary players — Dom Flemons, Rhiannon Giddens, and Justin Robinson — have carried that particular balance into their solo careers.

Any of the soundtrack’s shortcomings weren’t the fault of the musicians, who play and sing these songs much more beautifully and sympathetically than the film ever demanded. Nor is it the fault of the songs themselves, which obviously spoke to people as clearly in 2001 as they did in 1937. And it continues to speak loudly in 2021: The coffee table product wasn’t designed to bear the burden of the market it created, but the songs still inspire subsequent generations well into a new century, with its own tribulations and hardships.