Raised by a creative writing teacher and a music-playing biology professor who occasionally picked with Joan Baez, Oliver and Chris Wood were both destined for careers making music. Following time apart in the ‘90s – Oliver in Atlanta playing with King Johnson and Chris in New England staying busy with Medeski Martin & Wood – the Wood Brothers came together in the early 2000s during a co-bill between their bands in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

And they haven’t looked back.

In 2004 the Wood Brothers – their trio rounded out by multi-instrumentalist Jano Rix – officially arrived. Two years later came their debut record, Ways Not To Lose, and with it signature hits like “Luckiest Man” that over two decades later continue to stand the test of time, even as the trio’s sound shapeshifts. That sonic evolution is front and center throughout the band’s latest effort, Puff of Smoke, which features everything from boisterous horns to slippery synths and a bevy of world influences stretching across multiple continents.

Wrapped up in the 11 songs’ American-rooted and globally influenced aesthetic is a feeling of mindfulness that ranges from serious (“The Trick”) to comedic (“Pray God Listens”) and borderline cynical (“Money Song”). A prime example also lies within “Slow Rise (To The Middle),” an autobiographical ballad about the band’s methodical rise to making and maintaining a stable living from their music – as opposed to an overnight rise to stardom that oftentimes fizzles out in the most dramatic fashion.

“The lyrics are pretty abstract, but they’re pretty specifically about all the people who had the meteoric rise and died because of a plane or motorcycle crash or even an assassination – as was the case with John Lennon,” explains Oliver. “We were thinking of very specific people in rock ‘n’ roll who burned out and died young when they were at the top of their game. With that in mind, it’s almost a song of real gratitude that that didn’t happen to us.”

Ahead of the release of Puff of Smoke Chris and Oliver caught up with BGS to discuss the band’s roots, trajectory, experimental nature, mindfulness, and more.

(Writer’s Note: The following includes two separate conversations combined into one and edited for clarity and brevity.)

What was it that brought [Oliver and Chris] back together after over a decade apart to first form the Wood Brothers?

Oliver Wood: Having lived apart so long and played in different musical circles we were somewhat disconnected – both musically and and just as brothers – but we did stay in touch. In Medeski Martin & Wood’s early days they used to come to Atlanta and sleep on my floor before they blew up. I was always interested in the music [Chris] was making and he was interested in music I was making, but we just weren’t close.

At one point, it just happened that we played a show together where my band, King Johnson, opened for them – I believe it was at a place called Ziggy’s in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. We ended up having the best time and then they asked me to sit in with them on guitar on a few songs. [Medeski Martin & Wood] didn’t have a guitar player and I wound up fitting right in with what was going on [that] night. During it we stood next to each other and felt like we could just read each other’s minds, like we had this uncanny psychic (and obviously genetic) connection, musically.

In spite of the differences in the music that we were playing there was a lot of overlap. Both bands were really into traditional American music like blues and funk and jazz. It was like a musical conversation that went really well, so from then on Chris and I made efforts to play and write music together when we visited our family or had gatherings purely out of joy.

We had this thing in common, were all grown up, and had shed some of that brotherly baggage that family bands who’ve been playing together since they were kids sometimes have a harder time shaking, because they don’t never get a chance to form their own identities and feel like they’re their own person. It made it especially exciting to join forces and see what kind of recipe we could come up with everything we’ve learned over the years.

Chris Wood: One thing that’s not obvious looking from the outside in is how much overlap there was with [Medeski Martin & Wood] and what [Oliver] was doing with King Johnson. MMW formed in New York City in the early ‘90s in a very particular music scene where we were always trying new things and mashing together genres and finding new ways to play instruments. We operated with a fringe set of influences that included field recordings from West Africa and all kinds of other weird things that were out there compared to contemporary classical music, but when King Johnson opened for us in the early 2000s and Oliver sat in with us there was an immediate connection. In a way, it almost felt like I was watching myself playing because I could relate so well to his musical choices and approach to playing. He was a natural fit, leading to a moment that sparked the thought about doing something together that has lasted for over 20 years now.

It sounds like the time you guys spent apart has been critical to the bond you have, both as brothers and as bandmates, now over 20 years into the band’s life.

OW: Exactly! And I would say it also contributed to the unique sound that we were able to create because we were bringing some pretty different things to the table. I was really into blues and roots music and Chris went more of the jazz route, but he always said, “Well, what if you mixed Charles Mingus with Robert Johnson or Willie Nelson?” So the idea was to fuse together some things that you haven’t heard yet.

I feel like Puff of Smoke, with its barrage of horns and synth-heavy moments, is a prime example of that fusing together you speak of. What led you to incorporating more of those sounds on this album?

OW: Well, I think that’s always our goal, trying things we haven’t done yet. And a lot of times the metaphor for me is that we’re just trying different recipes. I’m still going to play guitar, Chris is still going to play bass, Jano is still going to play drums and keyboards. There’s going to be singing, there’s going to be familiar sounds, but we think of all these ingredients. There’s Calypso and African music and Chicago blues and gospel and a bunch of other things. These ingredients aren’t uncommon, so what makes artists unique is what they come up with from those sounds.

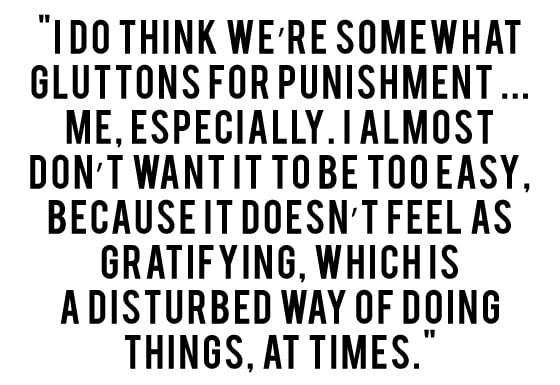

Oftentimes when we go in to make a record, it’s not conscious like, “Oh, we’re gonna make this kind of record.” We just know that we’re not going to do what we did last time or what somebody else is already doing, if we can help it. We’re trying to find something new that excites us and what that looks like is sometimes having a song written and ready to play, but going into the studio and saying, “I’m going to use this weird guitar that kind of sucks and see what it does.”

There’s an infinite number of combinations and ideas you can apply in the early stages of recording that really influence how different it ends up being. Our philosophy is to create a new recipe each time, which is why it’s so hard to pigeonhole us. That’s not good for business sometimes, but at the same time that’s what we’re going for because we’re trying not to fit in.

CW: We never know what we’re gonna do. What we end up doing is always based on what we’ve done in the past, which is wanting to push boundaries by continuing to evolve and try things we haven’t done before. Over the years we’ve surrendered to the fact that good things happen with the music when we’re not in control and we’re just paying attention to what’s happening and following each other’s lead instead of having a hardened idea of what things should look like. Usually that’s what kills the creative spirit, so relinquishing that control has always been a big theme for us.

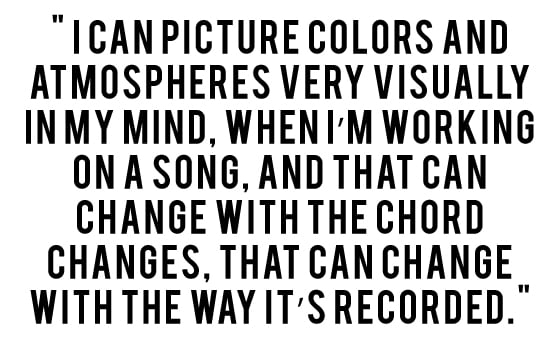

We all have a lot of respect for each other and our opinions. Creating artistic things can be a rabbit hole that you get lost in quickly, so being around people you trust can prevent you from doing that in favor of encouraging you when something is really working that you couldn’t even see yourself. When we bring a song we’ve written into the studio, we have absolutely no idea how it’s going to turn out because even though there’s lyrics (and maybe even a key) we make a lot of very spontaneous decisions about what kind of guitar to use or which drum set should there be. Every little decision like that leads to a new spontaneous reaction to how that instrument is sounding. That in turn makes us play a certain way, then by the time the songs are on tape we’re all blown away at how differently it turned out than we would have ever thought.

A big theme throughout these new songs is mindfulness. Can you tell me about how y’all practice that, both in your daily lives and your musical pursuits?

OW: For any artist, whatever’s going on in your life or the world around you makes appearances when you’re writing music – it just seeps in there and gets baked in you. Over the years, all of us in the band have been trying to live a certain way by learning methods and tricks to finding peace and fighting depression and the scary changes going on in the world while continuing to stay connected with people. I’ve always written like a cheerleader for myself, like “The trick is not to give a damn,” but by no means am I a master of any of that stuff. It’s a reminder to myself and others to always keep that on your radar. But on “The Trick” I follow that line with “Good luck,” so there’s a little bit of cynicism there too. Another song, “Pray God Listens,” is meant to be a little humorous and a little cynical of God, but also hopeful. It’s also about wanting to believe that God is listening and that I’m skeptical, but haven’t given up.

CW: [Mindfulness is] a constant recurring theme for us, even going back to [2023’s Heart Is A Hero] and the idea of remembering to remember. I think the hardest thing about presence and mindfulness and being an agent of your own emotions is just remembering it’s even an option. We get so carried away by the constant churning of our minds that you forget it’s even an option to not take that stuff seriously. There’s lots of references in our music about that – this weird storytelling device that we have between our ears that never shuts up and how to live with it – and the idea of control and surrendering to the fact that the only thing we can control is to be present. A lot of our anxiety stems from not knowing what to do, but if you just pay attention to your environment it tells you what to do.

This becomes really useful for us when we’re on stage in front of a bunch of people and the part of your mind that takes credit for and wants to be good doesn’t want a slow rise to the middle but instead wants a meteoric rise to the top and will start fixating on how to be great at something to the detriment of not paying attention to what’s happening around you. For me to play a good bass line I don’t need to listen to myself, I listen to the drums and guitar and those tell me how to play. That’s what presence is for us – it’s allowing our environment to tell us what to do, not trying to figure it out alone.

Another way of describing the themes on this record is impermanence. Things happen and then they’re gone. We have very little control over most aspects of what happens in the universe, so really all you can do is just sort of pay attention, trust that you’re going to know how to react to all that craziness and surrender to the moment.

What about this record stands out to y’all from the rest of your catalog?

OW: For me personally, I feel like there’s more and more freedom to just do whatever the hell I want. We have our own label, so we’re doing things quite independently without the structure of a label or A&R or anything like that and we’ve been doing that for a long time. We’ve always joked that the band’s career trajectory has been a slow rise to the middle as opposed to a meteoric rise to the top. There’s a song by that name on the record that’s a bit tongue-in-cheek as we make fun of ourselves and how it took us years to land at a sweet spot in our careers where we play to around 1,000 people a night – which isn’t a lot compared to Phish or Springsteen – but enough to feel like we can make a living and be a little weird in what we do rather than always taking the conventional route. We can be a little more subtle and aren’t beholden to any one thing, freeing us up to experiment without the worry of needing to write another hit.

As far as this album goes … we really tried to combine our creative visions to see what we could make and we’re all really proud of the result. It was a very organic thing that took over 20 years of experience to make happen.

CW: Between the three of us, we have a lot of influences. When you first begin as a band you’re trying to find out who you are and what your sound is. With both the Wood Brothers and Medeski Martin & Wood we waited to introduce electric bass to the mix even though I play both because the electric bass signifies certain sounds.

For instance, with MMW in the early ‘90s having electric bass with instrumental music that was danceable made you think of jazz fusion, which wasn’t a category we wanted our music to fall into even though it was instrumental music that was sometimes danceable. Once we established our voice as a band we began to branch out, which is the same thing happening with the Wood Brothers.

We have so many influences that don’t fit into the genre boxes that a lot of people put us in in our early days, which was Americana and roots music. We have influences from all over the world, especially on this record. On this record we explored more of the Caribbean, Cuban, and Latin influences we have. Oliver and I are also into these great African guitar players that there’s a lot of overlap with in his fingerpickin’ blues. Throughout we try to find different ways to introduce those influences to the Great American Songbook-like material on this record. Jano is a very good salsa dancer and obsessed with Latin music of all kinds, and I’ve always been into that music as well. One of my favorite bass players is Cachao, who is like the Duke Ellington of Cuba and invented “the mambo.”

There’s things like that that you’re sometimes hesitant to put into the music you’re putting out, but over time as you establish your voice it’s like “why not?” Let’s have fun using those influences even if it’s not “American,” per se. This is the melting pot – we’re supposed to be able to use it all here.

What’s your biggest joy of getting to make music together?

OW: Both Chris and Jano are like titans of music. They’re both virtuoso musicians who are not only monster players, but very creative too. Medeski Martin & Wood was a very experimental band that made great efforts to do what we’ve been talking about, which is to not sound like anything else and really be themselves and allow their musical identities to come through without trying to. Sometimes in instrumental music and in the jazz world, it’s about technique and technical prowess and those guys were just pure artists. They were really trying to make beautiful sounds and odd sounds and dissonance. Sometimes you could dance to it and sometimes you just had to take it in because it was real trippy. And so Chris brings that spirit of virtuosity and creativity, as well as Jano. We first hired him as a drummer because he was such an amazing drummer and percussionist and had no idea he could play keyboards just as well. He’s like two guys at once.

No matter what I throw at them, they can throw something cool back at me, enhance it and make it better. We’ve been talking about the sort of mindfulness theme in some of the music, and it really is a way that we try to operate as a band and as players. It’s about staying connected with yourself and with other people. If we have a musical disconnect it’s because we’re not listening to each other. Music is always a conversation where you listen and you respond or you hear something and you react to it, so if you’re only listening to yourself you’re missing the point. It’s detrimental to the music, so we make sure that we’re listening to each other, and in doing so, we get into this mindful, sort of meditative trance where we’re just listening and having a conversation and not trying to fill all the spaces. It makes us a very cohesive unit and able to be ourselves.

CW: Learning how to be present – as cliché as it sounds – that’s where the joy is. The joy is finally learning that it’s not me, it’s everything else that tells me what to do. Every time we play music it’s amazing, even a song that we play night after night with that approach feels like it might as well be the first time. The hardest part about this idea is remembering to remember, so my way of practicing that is trying to remember throughout the day to ask myself a simple question.

It’s like a challenge – can you enjoy yourself right now? And sometimes it’s easy, because things are fine and you’re not in pain or there’s no drama going on, but it’s the most fruitful moments when there’s something difficult or boring like doing the dishes and I ask if I can enjoy myself? Do I have the ability? What does it even mean to enjoy myself right now? And the practice is that if I can do it enough in those times, then I should be able to remember to remember to do that on stage too. From that point on everything is obvious – I’m able to relax and listen to the drums play me. All the pressure just goes away because you realize you trust yourself to react to the environment, and that never gets old. It’s useful for both your daily life as well as on stage or in the studio or any time we’re creating music together. We’re always trying to make every experience joyful, which isn’t always easy but can be done with practice. It’s like a game, it’s playful – even if you don’t always have a smile on your face.

Photo Credit: Laura E. Partain