Artist: Joshua Hyslop

Hometown: Vancouver, BC

Latest Album: Westward

Personal nicknames: Do self-appointed nicknames count? I started calling myself “Uncle J Bird” long before I was an actual uncle but people didn’t really go for it. I still try it out every now and then. One of my friend’s kids genuinely thinks it’s my name. A few fans of mine once tried to build up some steam by calling themselves “Hyslopportunists” but, thankfully, no one else was on board. Oh, and my friend Brian once called me “Joshua Thighslop” after he saw a picture of me in short shorts but it never caught on.

Which artist has influenced you the most … and how?

I think it changes. I have definitely drawn heavily on the inspiration I get from Paul Simon, The Tallest Man on Earth, and Daniel Romano, to name a few. Plus I’m always finding new music that grabs hold of me and completely changes my lens for a season or so. But overall I think the artist that has had the deepest influence on me is Ray Charles. Not necessarily stylistically, although there is some of that, but more so because of the feeling his music and more specifically his voice, evoke in me. It’s been the same ever since I was a kid and I heard one of his songs for the first time. Something about his voice just feels like going home. I can’t really explain it, but every time I hear him I smile and it reminds me of how much I love to sing.

What other art forms — literature, film, dance, painting, etc — inform your music?

I find inspiration in all of those forms but I think the one that has had the largest influence on me is literature. I read a lot. In fact, every time I finish reading 10 books I post about them on my blog, even though no one has said the word “blog” since the early 2000s. I’m going down with the ship, I guess. It’s usually just a turn of phrase or a specific description, or maybe just the feeling the book evokes, but there have been no shortage of moments that I’ve reached down into the lyrical ether to find an idea or that last line of a song and come up with something largely inspired by a book or a line I’ve read. It’s also a great break from writing. Whenever I come up against the wall I take a few steps back and just read or go for a walk. I don’t try to force my way through anymore. I’ve never been happy with the results when I’ve forced a song. Reading helps fill up the word bank and shift your creative mind off of “the problem” for a moment — sometimes, just long enough to help you unlock that phrase you’ve been looking for. Sometimes, not. But then, at least, you were reading a good book.

What was the first moment that you knew you wanted to be a musician?

I actually always wanted to be a writer and had a really hard time calling myself a musician. I don’t read music and I don’t know any theory, so I’ve always kind of felt like a bit of an impostor when it comes to being a musician. But I do remember smoking weed with a friend of mine when we were maybe 15 or 16, which was right around the time I first picked up a guitar, and we were watching the Oasis DVD, Familiar to Millions, and we were in awe. After it ended we were both absolutely certain that we were going to be rock stars. I don’t know why or where that came from, but we were determined. So we formed a band and started writing songs and performed locally as often as we could. I still feel like a bit of an impostor sometimes, but they haven’t caught on yet, and I’m lucky enough to still be doing it all these years later.

What’s the toughest time you ever had writing a song?

It’s almost always tough. You get the occasional gem that takes like 20 minutes and feels as though it was already written and it’s just being delivered to you, which is an amazing feeling, but it’s also incredibly frustrating because the next time you try and write a song and it doesn’t just flow out of your pen you feel like you’ve lost your touch or that it’s all gone and now you’re finished. Most of the time it’s a bit of a struggle, like doing a pretty difficult jigsaw puzzle. It’s like, if you just focus and stick to it and don’t give up, eventually you’ll find it. But I’ve had a few that have honestly taken me years. In fact, I just finished a song last week where I had two verses and two pre-choruses finished since about 2016. They always came back to me and I could never figure out where to go. Somehow, last week, it finally landed. Now, I just have to hope that it’s actually good.

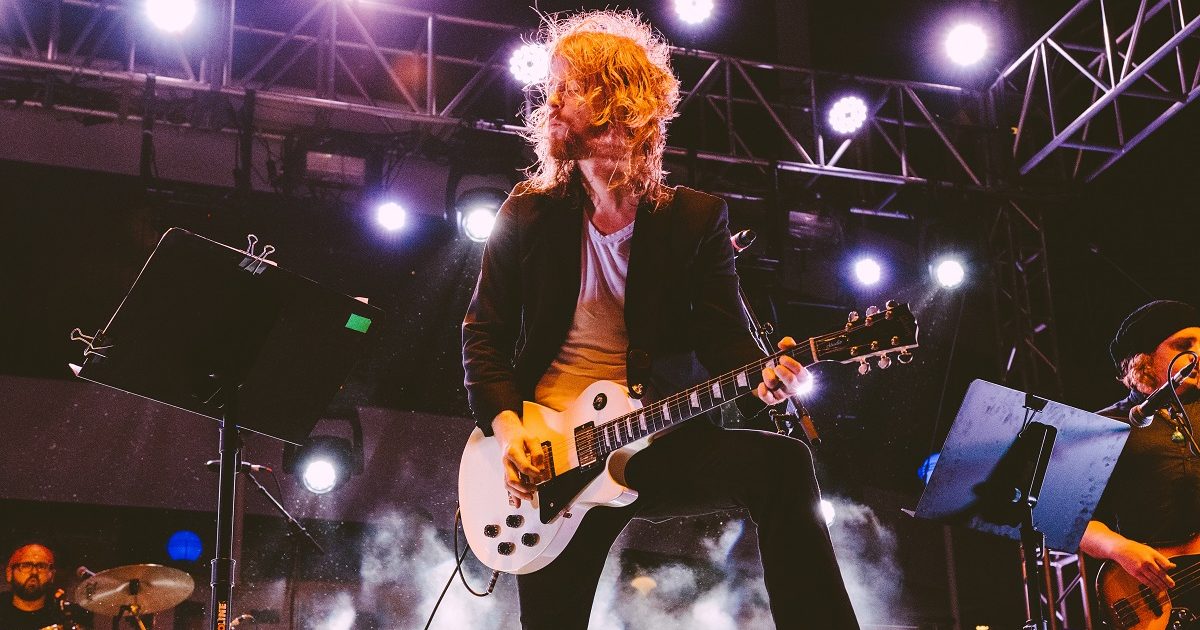

What’s your favorite memory from being on stage?

There have been many, but the first that comes to mind was when Mick Fleetwood invited me to play with him on his rooftop bar, Fleetwood’s on Front Street, in Maui. I’d never met him and I was only in town for a weekend to play a wedding for a couple who have since become some of my dearest friends. They were somehow distantly connected to him and someone showed him my music and he reached out about playing a show. He’d hired a cello player he’d been wanting to play with and said he wanted to play my songs. The three of us met a few hours before the sold-out show began and we played that night for around two hours. I think I’d maybe played with a band twice before in my life and only after we’d rehearsed extensively. But, magic happened and the three of us connected musically. It was one of those experiences that people call spiritual because it was so surreal it felt like it had to be otherworldly. I’m sure there were glitches as we played, but I don’t recall them. After the show, Mick said some incredibly kind things about me to the crowd and it was a moment I will never forget. The bar was kind enough to film the whole thing with GoPros and send me the files but I’ve never watched them. I got to live it and nothing can do that justice.