Della Mae have shaken up bluegrass and old-time stages for the better part of the last decade, with a mile-long resume that even includes a stint as cultural diplomats with the U.S. State Department. With Headlight, the Boston band’s first full-length album in five years, they’re providing their most powerful statement yet.

Written primarily on retreat at MOXE, a women-owned creative retreat outside of Nashville, the band taps into a more overt kind of activism than we’ve seen from them before, with lyrics that lift up victims of abuse, lend solace to the weary, and offer a single directive in the fight for change: to always keep moving forward.

Produced by Dan Knobler and recorded at Sound Emporium Studios in Nashville, the album features vocal powerhouses like the McCrary Sisters alongside instrumental heavyweights such as keyboardist Jen Gunderman and guitarist Molly Tuttle. Its tracks boast the fast picking and sublime harmonies that Della Mae fans have come to expect. BGS caught up with lead singer and songwriter Celia Woodsmith, discussing the new music and the band’s long record of working for equality in bluegrass and beyond.

BGS: The album opens with “Headlight,” a powerful song about standing up in the face of abuse. What drove you to write it?

Woodsmith: “Headlight” was definitely a hard one to write but it came out really quickly. I had been trying to write a song that could capture this feeling, the #MeToo movement feeling, and nothing was coming out. It really was after Christine Blasey Ford testified in front of Congress that it happened — the song came out in about twenty minutes, a very quick thing. I think I’d finally just had it.

As we [the band] have gotten older and more mature as human beings and as women and as musicians, it’s been easier and easier to not really care what other people think of us. [Laughs] It’s easier to say what we want to say, without fear that we might “ruin our career” or that the backlash will be too hard to handle. Truly, I didn’t write it as a political song, and I didn’t write it as something to divide people. I wrote it as an anthem, an ode to all the women in my life and the women I’ve seen all over the world who have stood up and been brave and been ridiculed for it.

Are there ways that you feel like your fans and your listeners could be “headlights” in their communities?

One of the lyrics is, “No need to be rude, just sit back and listen.” I think right now, especially, we really don’t listen to one another; we don’t want to listen to one another. There are a lot of takeaways that I hope people can grab from this song, but if standing up for women’s rights is beyond them, then I hope that they can just get through the song, just listen to it, just think about it. That’s all I can hope for.

As a listener yourself, what’s something in music in the last year or two that has made you particularly hopeful about what’s to come?

The first thing that comes to mind is the album by The Highwomen — Brandi Carlile, Maren Morris, Amanda Shires, and Natalie Hemby. That album, that project, really made me happy. First of all, that these women were badass enough to stand up and say, ‘This is a problem in country music. You don’t play our songs and you don’t play our albums, and we are absolutely going to stick this in your face.”

You have people constantly, your whole life, telling you that you’re “pretty good for a girl.” Believe me, Della Mae has gotten plenty of that. And it’s so frustrating. But when these high-profile women stand up for the rest of us, it elevates all of our voices. To have an album like The Highwomen do so well, be so well done — and by these four powerhouses — made me so hopeful for the future, hopeful that other young women are going to see this same thing and say, yeah, you know what? You should play our music. We are good enough.

Della Mae has been a presence like that for women all over the world, working with the State Department, performing in countries where women might not always see other women on stage. In your travels, were there times when you encountered a bluegrass community in places where people might not expect to find it?

Yeah, absolutely. We have found really amazing bluegrass musicians in Russia, and we’ve found them in the Czech Republic, and we’ve found them in France. Bluegrass is everywhere. It’s quite amazing to me, actually. We met a really amazing three-finger-style banjo player in Uzbekistan. This woman just learned how to do it from YouTube, and we were the first bluegrass musicians she’d ever jammed with.

Another time, these young Russian bluegrass musicians we sat down to pick with asked us to play [one of our songs] “Sweet Verona,” and they played right along with us. It was truly astonishing. That goes to show how small the world is. If you have an internet connection, you can listen to just about whatever you want, and you can learn. Bluegrass is a global thing, it’s everywhere. But it’s everywhere because it’s folk music, and I think that people can really relate to it.

I’ve seen quotes where Della Mae describe Headlight as the album you’ve always wanted to make. What were you enabled or empowered to do here that you haven’t been able to do in the past?

I think that kind of ties back into the “not-giving-a-crap-anymore” thing. We had always been afraid to have drums on an album, we’d always been afraid to plug in, use effects. [Because] we were in bluegrass, and kind of cornered into that genre, it felt like we couldn’t expand our musicianship, because we didn’t want to anger our fans.

We obviously care a lot about our fans, but [now] we think that we can take our fans with us, take them along for the ride. We’ve been playing for ten years. Our fans know that we can play a fiddle tune, and that we can play bluegrass standards. But we can also plug in and rock out and really perform songs that have meaning behind them, and do it with a lot of flair.

Do you think the pressure to adhere to tradition can be an obstacle for bluegrass musicians today?

I think that’s a problem being faced by bluegrass musicians, I think especially young musicians, but I think it’s getting better. Alison Brown, an absolute legend on the banjo, said it last year in her IBMA keynote speech: Change is coming to bluegrass, whether or not they want it. We have to start opening our arms more to different expressions of bluegrass.

There can be traditional bluegrass — that’s fine — but if someone has drums, or someone plugs in, or someone plays in an untraditional way, that doesn’t mean that we have to eliminate them completely from the genre. If we do that, then bluegrass music will slowly start to die. People won’t want to play it when they can’t play around with it, when they can’t give to it their own expression and their own creativity.

Recently I think there’s more openness to what bluegrass is, as opposed to what it isn’t. People will always say, “Well, that’s not bluegrass, they don’t have a fiddle,” or, “That’s not bluegrass, they don’t have a banjo.” More often lately, though, it’s been more like, “Oh, these musicians can play bluegrass, but they can also play a bunch of other stuff.” It’s better to celebrate that than to distance yourself.

Your new song “The Long Game” tackles the idea of temporary sacrifice for an ultimate goal. What are some of your challenges in playing the long game, and what keeps you looking forward?

We’re very lucky that this is our career, that we can travel around the world, meet people, write songs. But the day-to-day stuff is really hard. You’re kind of coaching yourself — “Just drink another cup of coffee and you’ll be fine.” When you’ve been a band for ten years, a lot of interpersonal stuff comes up. You may lose members over the years. We’ve had members turn over, and each time it’s difficult. It’s always the closing of a chapter, and then moving on a new way of thinking about Della Mae.

I love this band, and I love the women I play with, and I feel so grateful that we’re able to do this together. We’re really a family and a team, so I think that’s part of the long game, too — accepting change and learning to deal with it in a positive way, as opposed to a negative way. You’re always going to have surprises along the road, and you’ve just got to, well, keep playing the long game.

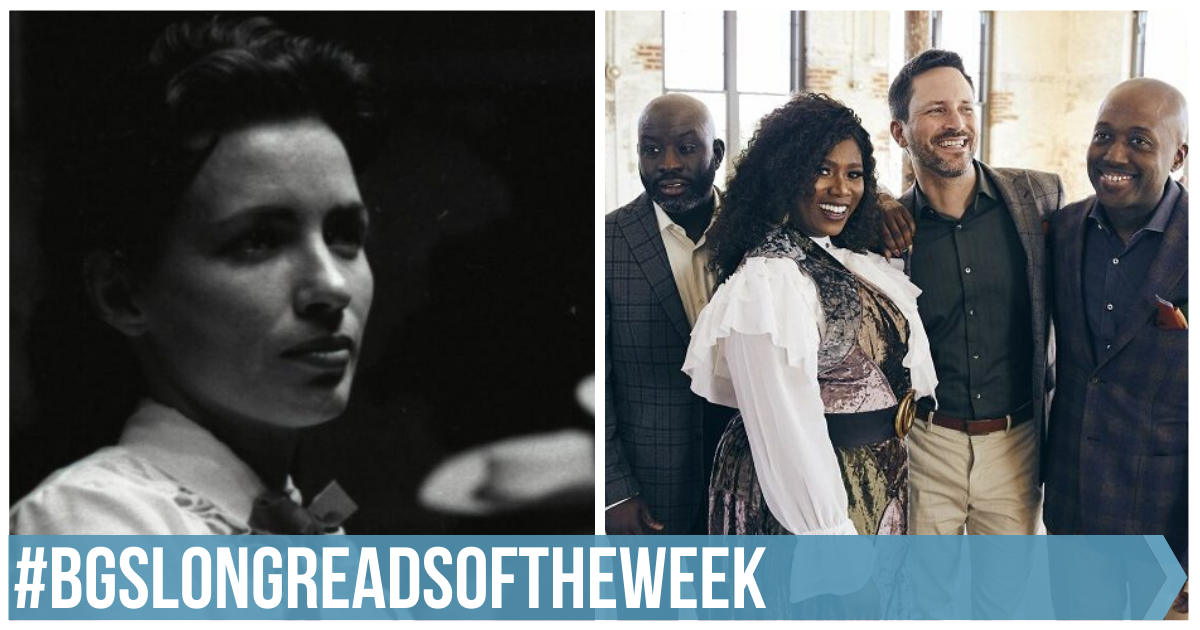

Photo credit: David McLister