Béla Fleck came to the banjo in quite possibly the oddest way imaginable — via The Beverly Hillbillies when he was a kid. Hearing Scruggs-style banjo on “The Ballad of Jed Clampett” while watching television, he was instantly smitten and fell in love with the sound. But he chose not to tell anyone.

“It would have made no sense to anybody else why I liked it so much, but it just took my breath away,” Fleck remembers. “It was this odd moment at my grandparents’ house, watching TV with my brother even though he doesn’t remember it at all. I never thought I could actually play that. It seemed impossible, not within human grasp.”

Afterward, Fleck got his mom to teach him enough guitar to play folk songs casually. He liked playing guitar, although it did not fire his imagination. But after his grandfather saw him playing guitar, he came upon a banjo at a garage sale and bought it for his grandson, who was 15 and about to start high school.

“Just this flukey thing,” Fleck says with a laugh. “’Here, you like stringed instruments, this was at a garage sale.’ I would never have had the nerve to buy one myself, and he bought it for me not even knowing my interest in it. Bringing it home on the train, I ran into a guy who asked if I knew how to play. I didn’t, so he tuned it in G, handed it back to me and I never put it down. Got a Pete Seeger book and got to work. It was a really profound thing and I became Type-A obsessed. Still am. I’m always thinking about it.”

That work ethic never changed, either. Bob Burtman was an early roommate of Fleck’s in Somerville, Massachussetts, in the late 1970s and recalls Fleck as the perfect roommate.

“Either he was off making money, or he’d be there endlessly practicing,” Burtman says. “He was so dedicated, you just knew how good he was gonna be. There was a mattress on the floor and he’d sit there playing scales for hours. Not typical scales, either — diatonic, weird Eastern European, just everything. Up and down, up and down. Word got around and people started hearing about him and dropping by to jam — people like Tony Trischka, Mark Schatz. I got to hang out and listen, which was fabulous. Béla soon moved on to bigger and better things, like his own apartment.”

Over the decades, Fleck has covered a lot of ground both literally and figuratively. He traveled to Africa to explore the African origins of banjo with the 2008 project Throw Down Your Heart and has also played jazz and classical as well as bluegrass with groups including New Grass Revival and his own Flecktones, winning 14 Grammy Awards. His most recent Grammy Award came in 2015, claiming best folk album for Béla Fleck and Abigail Washburn, made with his spouse and musical fellow traveler.

Strangely enough, however, he actually hasn’t done all that much straight-up bluegrass over the years. His latest album My Bluegrass Heart is a star-studded affair featuring notables old and new including Sam Bush, Michael Cleveland, Jerry Douglas, Billy Strings, Chris Thile, Molly Tuttle, and Sierra Hull. It’s just his third bluegrass album, and first in more than 20 years. But the timing does not feel coincidental.

“I always thought there’d be a time when I would want to do more bluegrass,” he says. “Growing up, it’s a great training ground before you spread your wings. Any great bluegrass musician has done that, pushed the edge, but they tend to want to come back when they realize how special the basic root is. Well, we had some family issues, my son got sick and we almost lost him. Once we knew he’d be okay, what to do then? Maybe it was feeling a lack of control, but I wanted to play music where I knew what to do rather than explore the unknown. I needed to connect with where I’d started, and the bluegrass community is one of the most beautiful things. You’re never alone when you play it.

“You know, I remember seeing Ricky Skaggs after he’d become a big country star, coming back to a bluegrass festival,” he adds. “He was this legit big star, and he played with eight bands that day. Bluegrass was still a part of him and servicing that part of himself and that community was important to him. That made a real impression. It’s important to me, too.”

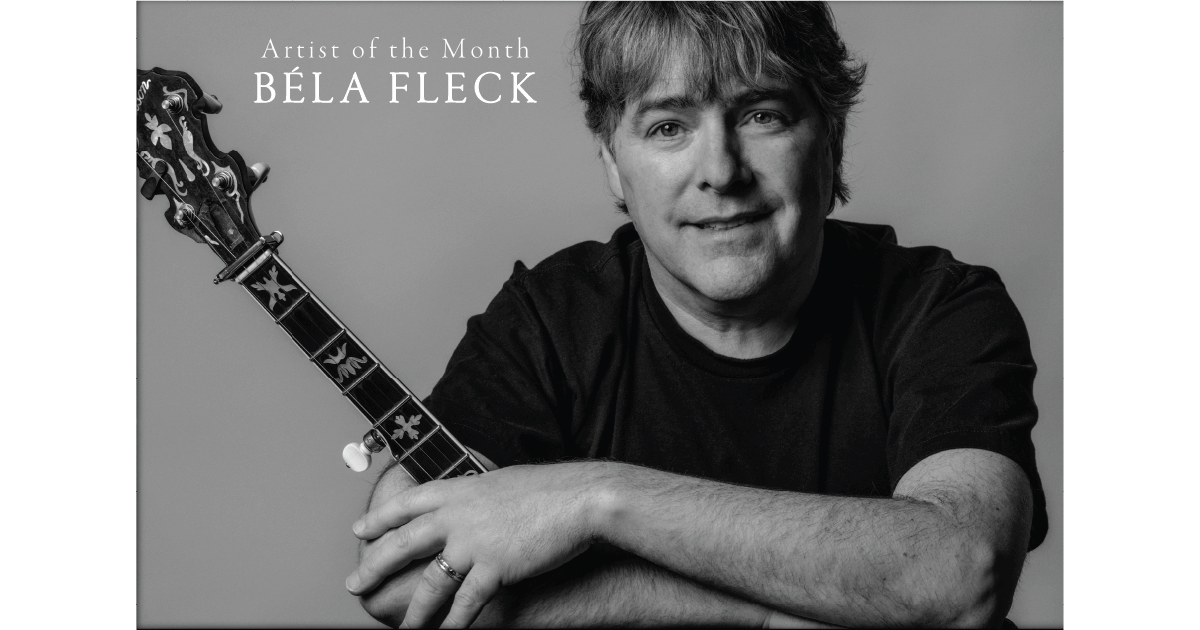

Editor’s note: Read about more about our Artist of the Month, Béla Fleck, here.

Photo credit: Alan Messer