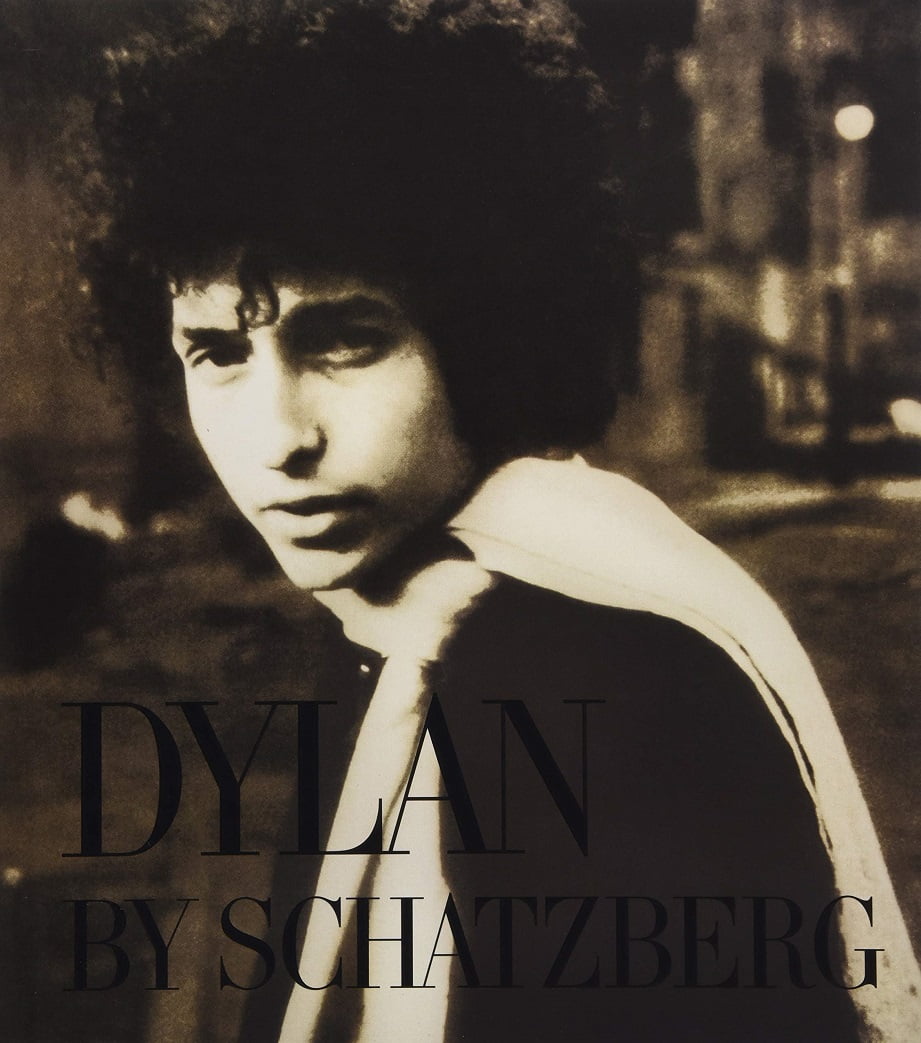

Six years ago just about now, J.S. Ondara landed in Minneapolis on a pilgrimage, lured by his love of Minnesota native son Bob Dylan’s music. He made his way north to Duluth, where Dylan was born, and Hibbing, where the singer-songwriter was raised. It was not quite what he expected.

“I thought I’d go to Hibbing and it would be a magnificent city with music coming from all over the place,” he says, now, laughing at his thoughts of the small town as the Emerald City. “There wasn’t much to find.”

We can forgive him his youthful fantasies. He’d never traveled like that before. He’d never seen snow before, let alone a Minnesota winter. He’d never really been away from home, and home was a long way from there — Nairobi, Kenya, where as a teen he’d fallen completely for the music of Dylan. But at just 20, he impetuously decided to trek to where his hero’s story began.

“It was all very romantic for me,” he says. “I just said, ‘Oh, I’m going to do this. It makes sense right now.’ It was all a very romantic choice, a thing I tend to do regularly in my life, make all these romantic decisions and not have any expectations out of it other than, ‘Let’s see how it goes.’”

That, uh, freewheelin’ spirit went pretty well for him. This month sees the release of his own debut album, Tales of America, on Verve Records. It’s a collection of moving, personal folk-influenced songs drawn from the journey he’s made and the observations along the way, produced by veteran Mike Viola (who as vice president of A&R at Verve signed him to his deal) and featuring appearances by such fellow Dylan acolytes as Andrew Bird, Dawes’ Taylor and Griffin Goldsmith and Milk Carton Kids’ Joey Ryan. The release comes on the heels of his first major tour, opening for no less than Lindsey Buckingham, and a subsequent European jaunt.

And while the Dylan influence is present, this is in no way an imitation or even homage, per se. With an almost jazzy looseness, often swaying around stand-up bass played by Los Angeles stalwart Sebastian Steinberg, there’s a closer resemblance to Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks. At the center is Ondara’s high, pure, finely controlled voice, an instrument unlike any of his heroes’, though you might hear some Jeff (and Tim) Buckley in it, at times piercing the heavens with an otherworldly falsetto, movingly unguarded on the haunting a cappella “Turkish Bandana.”

Hibbing wasn’t Oz, but he’s definitely not in Kenya anymore. And what swept him to this new life was, of all things, grunge and indie-rock.

“We really didn’t have much growing up,” he says. “Had food, a place to sleep and that’s about it. And a tiny little radio, about the size of my iPhone. That was all we had.”

Through that little radio came Nirvana, Radiohead, Death Cab for Cutie, transmissions from another world in a language the Swahili-speaking youth didn’t understand. It was magical.

“I was intrigued by the music and language, all these sounds,” he says. “I couldn’t make any sense of it. To me it was a spaceship to another universe.”

He tried imitating those sounds, though not knowing the language he sang gibberish — well, maybe not that far off with some of Kurt Cobain’s often hard-to-decipher mumbling. But it worked its way into him.

“I heard all these songs and developed a kinship for a long time, and used them to study English because I wanted to understand what Cobain was saying, or [Radiohead’s] Thom Yorke or [Death Cab’s] Ben Gibbard,” he says. “I was curious about the language and the spirit and that spurred me to learn English, and I built my vocabulary listening to these songs.”

Another song that caught his ear was “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” — the Guns ’N Roses version, which he assumed was an original by that band. It was only after losing a bet to a school mate about the song’s authorship that he discovered the music of Dylan himself. It was an epiphany.

“I wrote stories and poems, from a very young age,” he says. “I wrote about a puppy, about school, I wrote a lot about the sun for some reason. I was fascinated by the universe in general and wasn’t really receiving the answers I needed. So I would write poems and stories about it as a way to process it and learn about the world. But I never wrote songs. One reason I believe I was drawn to Dylan was listening to his records I thought, ‘These are poems with melodies! I could probably do this!’ I felt I saw a path for me. ‘Perhaps there is hope. I can take these stories and poems and put them in melodies and perhaps people could like them in a grand way. This is something people like? Great! Maybe I’m not lost in my path!’”

He soon set his sights on America, where he had a few relatives and friends scattered about, including an aunt in Minneapolis. But finding a way was rough.

“I started by applying to the University of Minnesota and looking for work opportunities in the state, but nothing bore any fruit,” he says. “As I ran into a wall and was running out of options, I was suddenly awoken, quite rudely, in the wee hours of the morning to be told that I had won a green card lottery and could move to the States. Turns out an aunt had applied for these green cards for a few of us and mine went through. I had no idea. The mischief of the universe!”

His family helped get the money together for the trip after he told them that he was going to become a doctor. That was a fib, he admits. Once settled in Minneapolis, he dove into music-making seriously.

“I picked up a guitar and learned a couple Dylan songs, a couple Neil Young songs, then would go back to those melodies and these poems I’d written, turn them into a melody, call it a song and then go out and try to play for people. That’s how it began for me.”

He hit up the open mic nights around town, started getting some small club bookings, “gradually, very gradually trying to get these songs in front of people.”

And with some money he’d saved from work via a temp agency, he made an acoustic EP that he put online. Soon a local public radio station put his songs in regular rotation. Word spread and contacts started to come in from the music business, both in Minneapolis and around the country.

Among those reaching out was Viola, a veteran musician (the band the Candy Butchers, as well as singer of the title song from the movie That Thing You Do) who had recently taken the job at Verve. The two hit it off right away.

“I had done meetings with others, but with Mike there was a connection,” he says. “I’d do meetings and mention favorite Dylan records and no one knew what I was talking about. Freewheelin’ remains my favorite. When I met with Mike I brought this up, the idea of trying to make a very stripped-down record like that. A few things happen, but not crazy, doesn’t take away from the stories. And I brought up Astral Weeks, which does the same thing. A few things on it that embellish the stories. Those two records. He went, ‘Oh yeah! Those are my favorite records, too!’ There was just chemistry I hadn’t had before.”

From there it was simple.

“It was the old troubadour style of making folk records,” he says. “You get into the studio — you wrote a bunch of songs and maybe get some people around you and play this, and that’s the record.”

The result is an album that portrays the wonder and delight — and also the struggles and heartbreaks — of his time in America, with a facility for language that escapes most native speakers. (An essay he wrote about his life, “The Starred and Striped Fairy of the West,” shows another facet of that.) The opening song, “American Dream,” is equal parts welcoming embrace and distancing suspicion, his poetic images boiling the national spirit to an intimately personal level, a dream world, as it were. That inner view is there throughout the album.

It all came naturally from his experiences.

“I wrote the words ‘I’m getting good at saying goodbye’ just a month after moving to America,” he says of the chorus of the somber “Saying Goodbye.” “They were just words at the time. I didn’t know what they meant. But after turning them into a song and singing them over and over, I can see that I was grappling with thoughts of the past and future. I could see that the totality of my past — being family, culture, upbringing, all of it — was stopping me from becoming not just who I wanted to be but who I’d be best at being, which is the true ‘self’ within.”

That said, he’s also found that echoes of his past can be heard in some of these songs, even if very faintly. He wasn’t a big fan of Kenyan music, traditional or modern while growing up, but it seems some of it crept in anyway. A few of the songs, notably the loping “Lebanon,” bear rhythms echoing those common in music of that region of Africa — the national benga or Nigerian highlife, Tanzanian taraab and Congolese soukous, all quite popular in Kenya. And there’s something ingrained in the vocals that even Ondara only heard after the fact.

“I was listening back to some of the songs and I can hear toward the end of some that I start to make some sounds influenced by my native language, which is not something I tried to do,” he says. “There is African influence there, but subconscious. The more I listen, the most I can track down those sounds.”