[Editor’s note: Photos by Carl Fleischhauer]

On Monday August 7, 1972, with fresh memories of Maritimes old-time and bluegrass, I drove from New Brunswick to New England to join my wife and kids, who were house-sitting for my in-laws in Norwich, Vermont.

On Thursday the 10th I headed south. A fourteen-hour drive brought me to Morgantown, West Virginia, the home of my friend and partner in research, photographer and film-maker Carl Fleischhauer, then employed at West Virginia University. We’d known each other for twelve years. (Our stories are in Bluegrass Odyssey: A Documentary in Pictures and Words, 1966-86 [U of IL Press 2001]). We were about to embark on fieldwork.

During the preceding year, when I began planning for the book Bluegrass: A History, I asked Carl to help me think about photos. In addition to documenting bluegrass festivals and other venues he, with Sandy Rothman, had recently looked for traces of earlier days in a field trip to the old Monroe home in Rosine, Kentucky. Now, we made plans for our own field trip. Carl would take photos. I would make notes and do interviews.

We spent that Friday in Morgantown looking at Carl’s photos and films and listening to LPs as we prepared for the research. At the end of the evening, my notes say,

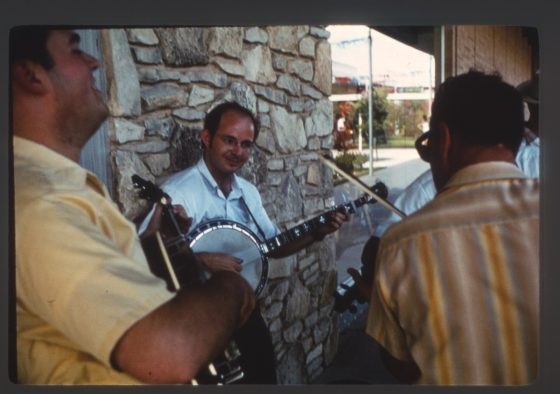

Did some picking.

Early Saturday morning we piled in my new Toyota with our gear (cameras, tape recorder, axes, tent, sleeping bags) and headed southwest, crossing into Kentucky from Huntington, WV and snaking down through the mountains to Jackson, the seat of Breathitt County. Three hundred miles; we arrived around 2 o’clock.

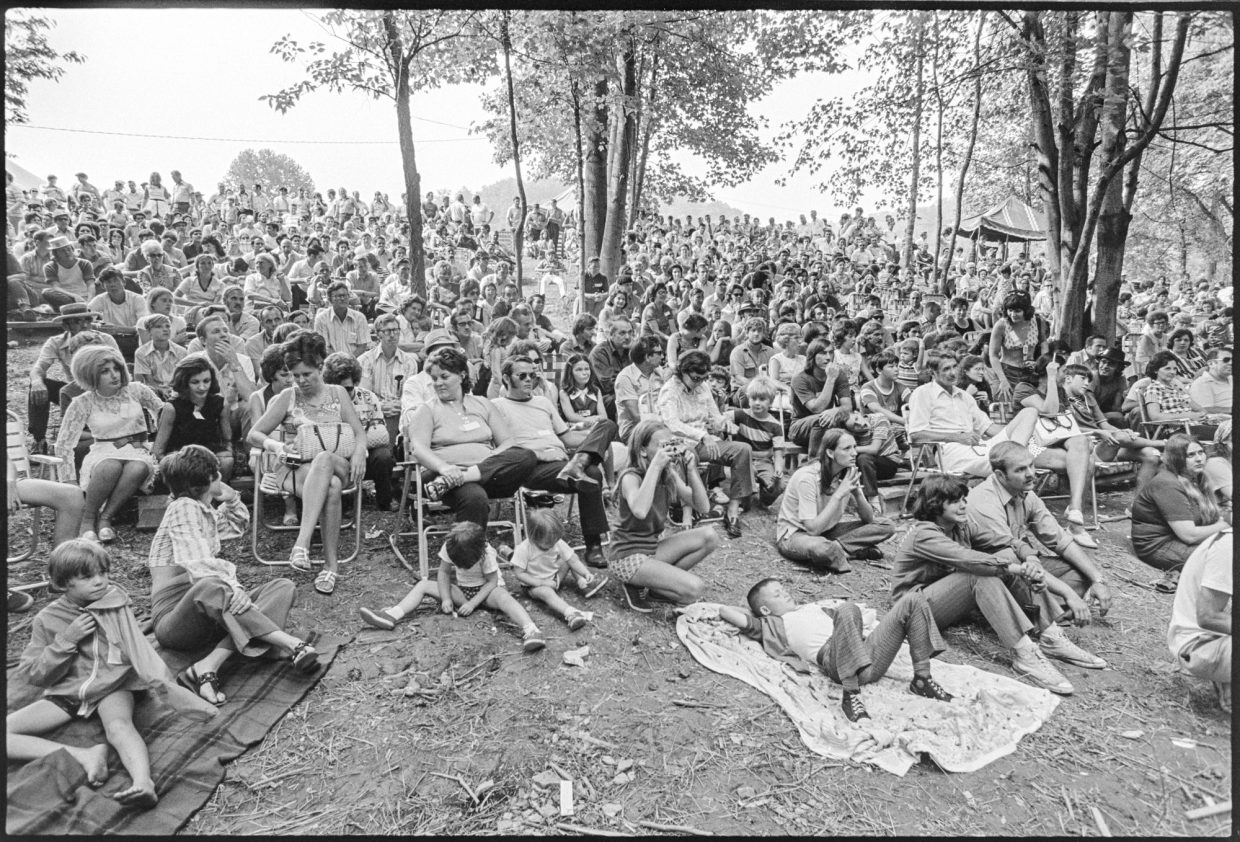

There we headed just outside of town for Bill Monroe’s Second Annual Kentucky Blue Grass Festival. When I went to Canada in 1968, Bill Monroe had one festival a year at Bean Blossom in Indiana. Now he was running a bunch in other states, as were other artists. Festivals were the big news in bluegrass music in 1972. We sought to document the bluegrass festival experience.

Later others would write about this, like Bob Artis (“An Endless Festival” in Bluegrass [1975]) and Robert Owen Gardner (The Portable Community [2021]). Here’s how my notes from Jackson begin:

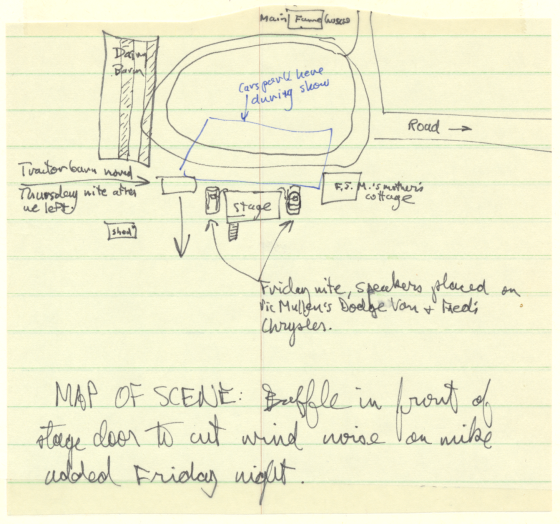

West of town on main hwy, down short steep road. Paid camping & Sat. fees, never did pay for Sunday. Parked & walked down to the stage area — tent set up, natural amphitheatre, uncovered stage, bad sound. Lots of cops around on Saturday.

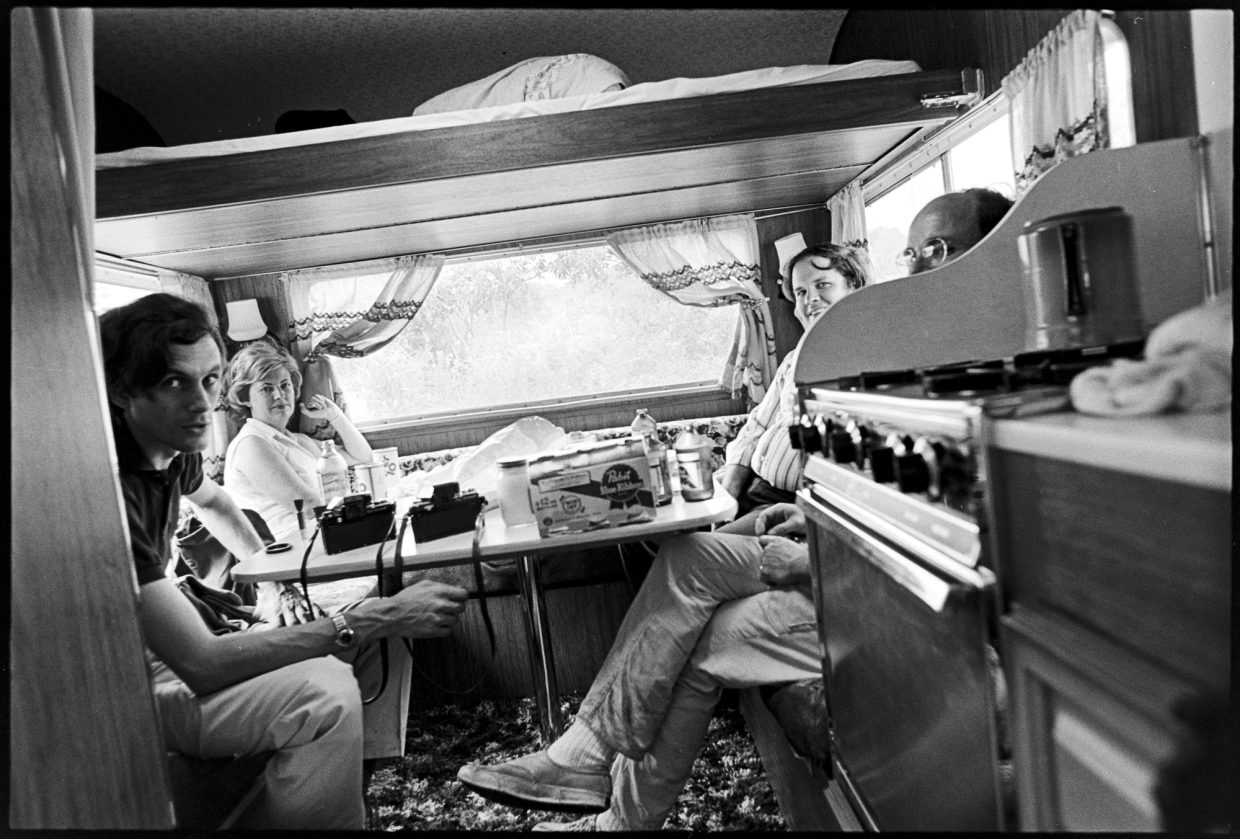

Made contact with Pete & Marion Kuykendall, and agreed to move in next to them to camp. Set up tent, attempted to speak to Monroe but he was busy coping with the Goins Bros. problem of being hassled by the cops for drinking. Later Kuykendall said that cops had asked Monroe for $ (3 or 6 hundred) and he had refused to pay off so they were taking it out in fines. Lots of racing around on Sat. with flashing lights et al, but they stayed away on Sunday.

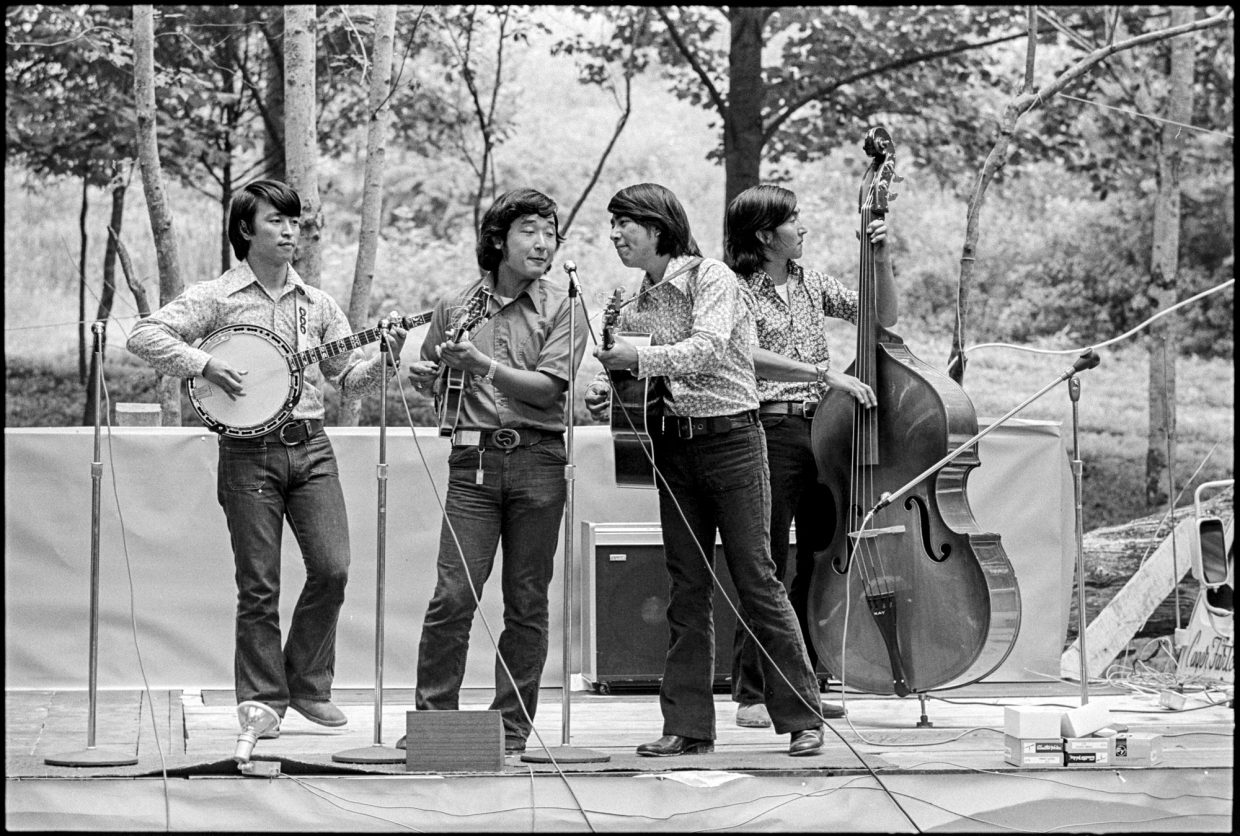

Listened then to IT’S A CRYING TIME, hot & exciting Japanese bluegrass band. Then back to Kuykendall’s bus/home whatall. Thunderstorm; discovery that cassette recorder didn’t work on batteries because plug distorts switch; got it running eventually. Oldest Kuykendall girl Sam/Ginger comes in with bass player of above-mentioned Japanese band, then leaves. Kuykendalls are a bit worried about this but Carl & I both notice later that a number of young girls (McLain girls, for example) are hanging around, with this group.

Dinner with Kuykendalls. Frank & Marty Godbey come in and are around for the rest of the evening. Mostly we sit & talk, though I went down to the amphitheatre to catch Jim & Jesse and the Japanese bands. Came back, then returned to catch Monroe. Afterwards listened to picking group in tent near us. Did mainly Emerson & Waldron, Newgrass Revival, Bluegrass Alliance, Gentlemen, etc. Chromatic banjo. Noisy night in Carl’s tent, as sessions went on late and busses started early. I got a spider bite.

I’d known the Kuykendalls since 1966. Pete, a 1996 inductee to the Bluegrass Hall of Fame, was a musician, record collector, producer, publisher, and, since 1970 owner-editor of the first and leading bluegrass monthly Bluegrass Unlimited.

Pete and I had already been corresponding about bluegrass history when we met on Labor Day weekend 1966 at the second Roanoke Bluegrass Festival. Subsequently, I visited the Kuykendalls in Virginia where Pete encouraged me to write for the then all-volunteer magazine he would later own. I began with a review of the festival, published the following January — the first of eight articles I did for BU in 1967.

By 1970 Pete and Marion were running BU full-time; I’d done an article for them earlier in 1972 (eventually I would write a monthly column) so we had been in touch recently by mail and phone. Conversations with Pete were never brief! He loved to share the business scuttlebutt and he had plenty since they were selling the magazine at festivals every weekend and had just launched BU’s own annual festival.

I think this may have been the first time I met the Godbeys. From Lexington, and before that, Columbus, Ohio, they had been following the bluegrass scene for a decade. Frank is a musician who is still performing these days. By 1972 he and Marty had begun writing and publishing photos in BU. For them, as for me, hanging out with the Kuykendalls was a good way to keep up on the bluegrass news. People were already talking about starting an industry association, though that — the IBMA — wouldn’t happen until 1986. Pete was one of its founders.

With the growth of the festivals came clubs, newsletters, and magazines. Bluegrass enthusiasts (many of them musicians) followed their favorites to festivals and other venues. Paths crossed; networks grew. The politics of bands was a favorite discussion topic.

Over the course of the festival, I made note of gossip about the always changing bands. Ricky Skaggs had just left Ralph Stanley — there were rumors about where he was headed next. Was Bill working to get Ralph Stanley on the Opry? Some thought so. The II Generation was said to be splitting up. Stories were told of bluegrass festival camp followers.

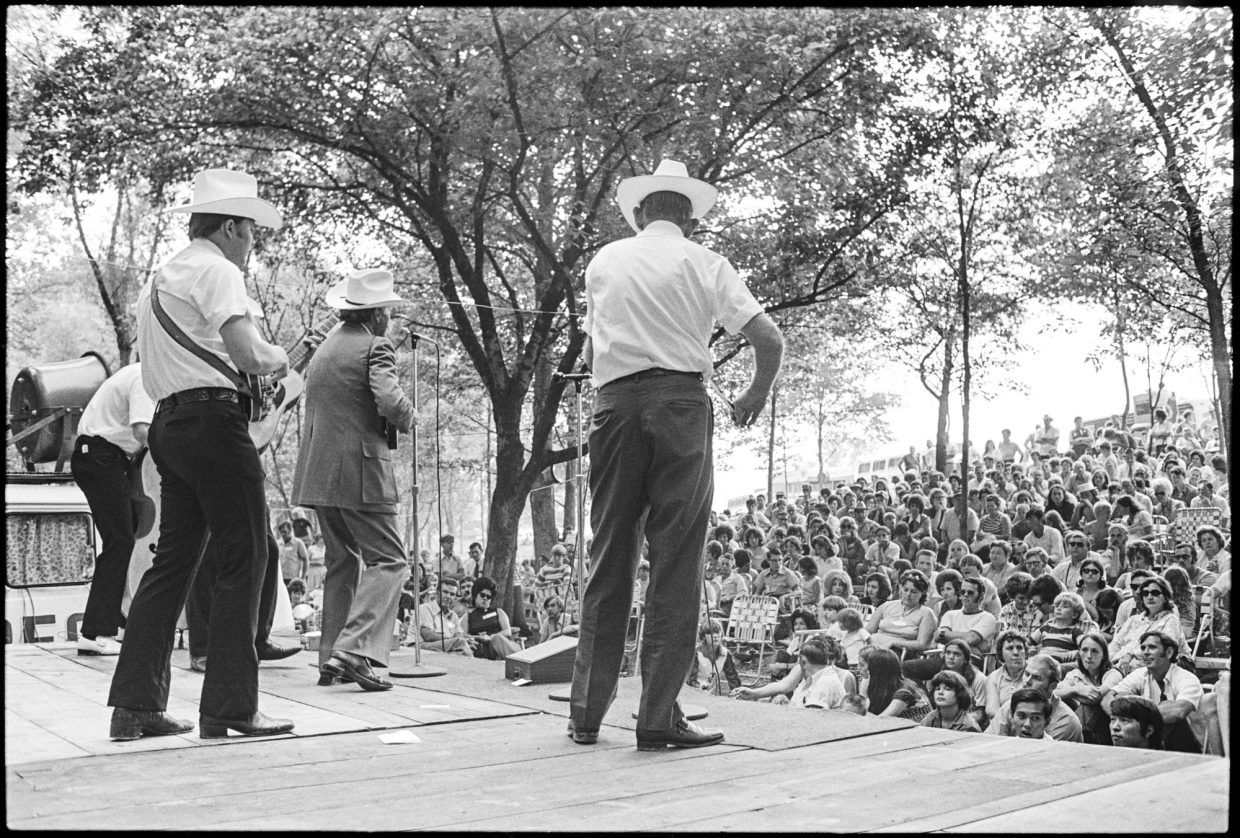

At this Jackson, Kentucky festival were a bunch of bands that had been appearing at Bill Monroe’s other 1972 festivals — Monroe, Jim & Jesse, Flatt, Reno & Harrell, the Goins, Ralph Stanley — mature musicians who’d been working with this music for a substantial period of time and who stuck close to the early models of which they were, often, the authors. Classic bluegrass, one could say.

What the audience didn’t hear was the kind of stuff we’d heard from the jammers late Saturday night, like “One Tin Soldier,” The Bluegrass Alliance’s cover of a song popularized in the film Billy Jack. Their bluegrass version, with Sam Bush’s lead voice and Tony Rice’s harmonies and guitar work, was a hit, a big step on the road to newgrass.

The Japanese bands were new to the scene. Japanese bluegrass began in the early sixties. In 1971, Bluegrass 45 came from Kobe, Japan, with the sponsorship of their label, Rebel, to tour U.S. bluegrass festivals. They made a big hit at Monroe’s Bean Blossom festival with their showmanship and musical savvy. This year they were back, along with another Japanese outfit, It’s A Crying Time.

Monroe had booked the Japanese bands as a novelty, something you couldn’t see just anywhere in the bluegrass world. As I mentioned in my field notes, I found It’s A Crying Time’s music “hot & exciting,” and I was not the only one in the audience reacting this way. They came to the attention of Lester Flatt, who, after watching them rehearse, invited mandolinist Kazu Onishi to join him on stage at his final set.

Lester Flatt, and Akira Otsuka. Otsuka was Kazu’s friend from the Japanese scene, a member of the Bluegrass 45.

This video comes from the Bluegrass 45’s appearance at Carlton Haney’s Camp Springs festival:

They are announced at the beginning of the video by emcee, writer, and DJ Bill Vernon. Vernon was here at Jackson, as I learned Sunday morning when I went down to the early morning gospel show. Pete Kuykendall introduced me to Bill there, and we had a long chat about the politics of the bluegrass industry. I wrote in my notes:

A very loquacious and complex person.

At that morning’s gospel show, the music came to a stop as a fundamentalist preacher began his sermon. At that point, I noted:

Bill Vernon cut out from the morning sermon, he’d had enough…

I stayed and heard some good music, noting:

The gospel section’s high point was when the Goins Bros. did “Somebody Touched Me” and Eleanor Parker came on stage & started clapping hands and singing; Monroe caught on and came up to join in too.

This kind of spontaneity, which gave festivals their appeal, was not there all the time. Jim & Jesse, I wrote, had:

A good show, with Jim Brock sounding especially good, but … a cut and dried quality to it all.

Describing Lester Flatt and his Nashville Grass, I concluded:

To me the whole band sounded tired, lackluster.

But Flatt’s final set was enlivened when It’s A Crying Time mandolinist and tenor Kazu Onishi came on stage to sing “Salty Dog Blues” with him.

During my times around the stage area, I had a chance to talk with Monroe and with some of the musicians I’d gotten to know during my years as a backstage regular at Bean Blossom, like Birch Monroe, Joe Stuart, and Roland White.

I arranged with Birch, who was busy helping Bill run the festival, for an interview, to take place later in the week at his home in Martinsville, Indiana.

Joe told me about his experiences playing bluegrass in Canada with Charlie Bailey. He’d even appeared in Newfoundland.

Roland, whom I’d known since his days as a Blue Grass Boy, was now playing with Lester Flatt. He told me they were working solid, playing festivals every weekend.

Here’s what I wrote about the audience:

Audience — bluegrass die-hards from Ohio, Ky., D.C., Carolinas. Few freaks. Appear to be about 50% campers, 50% local people. Certainly no more than 1500-2000, on Saturday, though figure of 3000 was bandied about. Bill moved his Ky festival to Jackson from Ashland this year because the turnout at Ashland was dropping. Fact, bluegrass ain’t as popular in Kentucky as it is elsewhere — Ohio, D.C.

The festival closed with a finale, orchestrated by Monroe. At the first festivals in the mid-60s, which were created to honor Monroe, such events were somewhat spontaneous, but by now, seven years after the first one, these events were highly ritualistic. By the time it happened, I noticed that the Kuykendalls had left. They were not the only ones.

We packed up soon after and headed west for Lexington. I was hoping to interview J.D. Crowe.

[To be continued]

Thanks to Akira Otsuka and Carl Fleischhauer

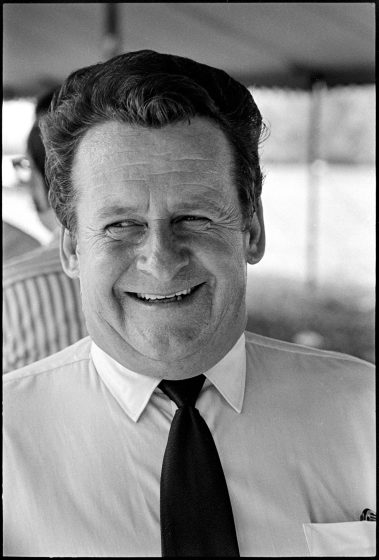

Rosenberg is an author, scholar, historian, banjo player, Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame inductee, and co-chair of the IBMA Foundation’s Arnold Shultz Fund.

Photo of Neil V. Rosenberg by Terri Thomson Rosenberg.

Edited by Justin Hiltner