The beautiful voices of I’m With Her paid special tribute to the illustrious icon Dolly Parton in their latest visit to the studio for Live from Here. In an intimate performance, I’m With Her sing “Lover’s Return,” originally a Carter Family song, which Dolly, Emmylou Harris, and Linda Ronstadt revived only a few years before the turn of the century on Trio II. Now as a new decade is settling in, I’m With Her look back and remember, breathing new life into music that inspired so many — including Sarah Jarosz, Aoife O’Donovan, Sara Watkins, and of course, Dolly herself.

Tag: carter family

LISTEN: Joe Hott, “Sweet Loving Lies”

Artist: Joe Hott

Hometown: Augusta, West Virginia

Song: “Sweet Loving Lies”

Album: West Virginia Rail

Label: Rural Rhythm Records

In Their Words: “‘Sweet Loving Lies’ was written by Glen Duncan, Adam Engelhardt, and myself. A lot of the songs we write have a Stanley Brothers feel, but with this song, the way it was written and put together it has a strong original Carter Family feel, lyrically. I was so excited when we came up with the line ‘Spring flowers were bloomin’ when you came to me.’ It really set the tone for the song and you could just hear Sara Carter singing that line as only she could. The original Carter Family has been a big influence on me over the years and to have a song that resembles them on this new album is amazing. ‘Sweet Loving Lies’ is a great old school song that I know the fans will enjoy.” — Joe Hott

Photo credit: Stacie Huckeba

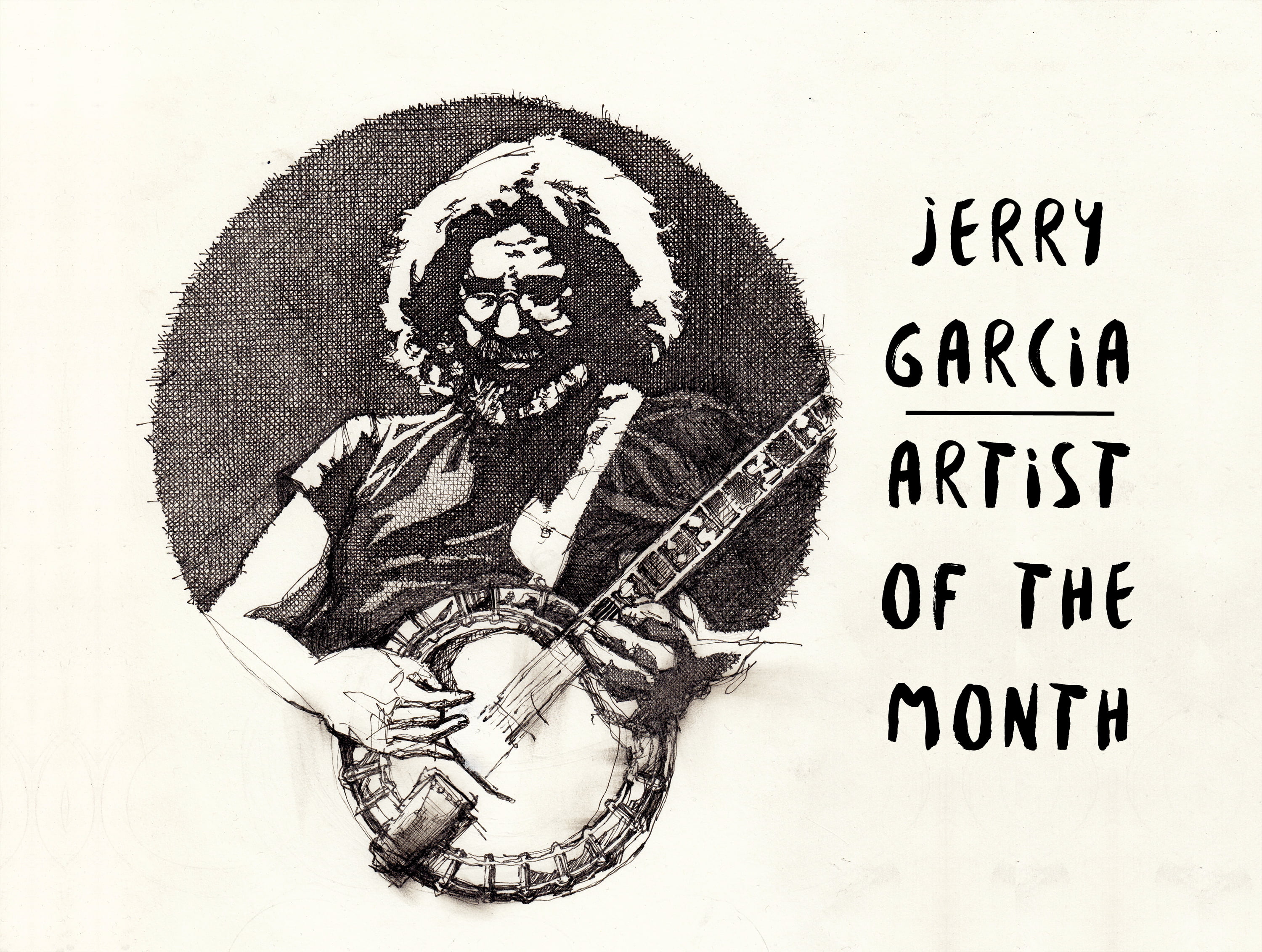

Jerry Garcia: Expanding the Musical Consciousness

Before becoming the psychedelic guitar-playing icon of the Grateful Dead, Jerry Garcia was already living a life completely dedicated to music. Heavily immersed in the folk idioms that coalesced with the beat poet scene in San Francisco — and in the peninsula towns of Menlo Park and Palo Alto — in the beginning of the 1960s, Garcia’s concentration, determination, and passion for musical collaboration planted the seeds for a force that would not only influence the world in song, but that would let loose a seamless tie to multiple genres through multiple generations. What’s now viewed as Americana, Garcia was creating with the Dead right from the outset. His impact looms far and wide, perhaps even greater as the years since his passing roll on. From the bluegrass world of the McCourys to esteemed guitarists like Mike Campbell of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, David Hidalgo of Los Lobos, and David Rawlings, to jam bands like Leftover Salmon, and the current generation of musicians like the National, Jenny Lewis, and Ryan Adams, Garcia’s ethos is being deeply felt and utilized.

Garcia had a mind hungry for knowledge and interested in art, comics, and horror films, even as music ran through his family. After initially getting an accordion for his 15th birthday and successfully trading that in for a guitar, the quest for constant improvement was born as he devoured the styles of Chuck Berry, Jimmy Reed, Buddy Holly, and Bo Diddley. As the ‘60s approached and the initial rock boom faded, Garcia and his friend (and soon to be Grateful Dead lyricist) Robert Hunter found themselves in the middle of a very fertile Bay Area folk scene. Being steeped in Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music led to a fascination with the Carter Family and then Flatt & Scruggs.

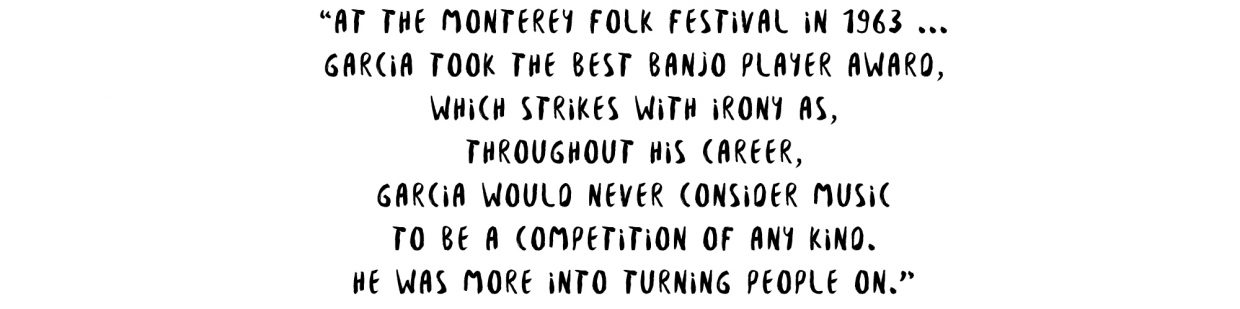

It was at this time, in 1962, that Garcia began his complete immersion into the banjo and the bluegrass style of Earl Scruggs. He formed the Hart Valley Drifters with Hunter and David Nelson (later of New Riders of the Purple Sage and the Jerry Garcia Acoustic Band), and the scene grew to encompass the likes of Eric Thompson, Jody Stecher, Sandy Rothman, Rodney Albin, Janis Joplin, Jorma Kaukonen, David Crosby, Paul Kantner, and Herb Pedersen. The Hart Valley Drifters performed at the Monterey Folk Festival in 1963 in the amateur division and won Best Group, and Garcia took the Best Banjo Player award, which strikes with irony as, throughout his career, Garcia would never consider music to be a competition of any kind. He was more into turning people on.

While absorbing as much music as possible and focusing on his craft with diligence, Garcia came into cahoots with people like Ron “Pigpen” McKernan and John “Marmaduke” Dawson through a string of continuous collaborations and a rotating cast of characters at joints like the Boar’s Head, Keppler’s Bookstore, and the Tangent. McKernan was the blues aficionado with the biker looks and heart of gold who would lead Garcia into the electric blues band the Warlocks, which then became the Grateful Dead, while Dawson would be the one who had the canon of songs for Garcia to base his pedal steel guitar learning around to form the New Riders of the Purple Sage.

But it was on a cross country road trip with Rothman in 1964 that Garcia met David Grisman, the young mandolin player to whom Thompson had tipped him off. It was at Sunset Park in West Grove, Pennsylvania, where acts like Bill Monroe and the Osborne Brothers were featured, where Garcia and Grisman first did some pickin’ together, and a friendship was born that would lead to musical ventures that would have more than a lasting impact.

Both Garcia and Grisman were imparted with some crucial advice from Monroe, which was to start your own style of music. Garcia, no doubt, led the Dead (as much as he refused to admit to any leadership role) to their unique musical domain, while Grisman created his own “Dawg” style of music that was the precursor of “New Grass” in the ‘70s. According to Grisman, “Jerry was always the true renaissance music man.”

While each had gone on to create their own paths, it was 1973 when they started hanging out together at Stinson Beach, picking and having fun, when Peter Rowan (a former Bill Monroe Bluegrass Boy member) joined in along with legendary fiddler Vassar Clements, and, needing a bass player, John Kahn was brought in. Old & In the Way was born. In typical Garcia nature, the musical fun led to some local gigs which, thankfully, were recorded by Owsley “Bear” Stanley. With the guitar and the Dead being Garcia’s main drive, getting back to the banjo and picking with his pals in Old & In the Way was not only stress free, but fun and a piece of his musical puzzle that really exemplified how the muse consumed him. It wouldn’t be out of the norm, at the time, to find him in the span of a week or two playing gigs with the Dead, Old & In the Way, and one of his other musical soulmates, Merl Saunders.

The release of Old & In the Way, taken from Bear’s recordings at the Boarding House in San Francisco in October of 1973, hit the world in 1975 on the Dead’s Round Records label. It was through the Dead Heads fan club mailing of a 7-inch, 33 rpm sampler that many fans got their first dose of Old & In the Way. Many of that generation — and a few that followed — were exposed to bluegrass thanks to that release. The album continued to turn on the masses and was widely respected as one of the best-selling bluegrass albums of all time.

While fame was never of interest to Garcia, the expansion of musical consciousness was, perhaps, the most beneficial and unintended consequence of his popularity. Just like the Dead were doing with their music — turning kids onto Merle Haggard, Buck Owens, and Johnny Cash songs — here, Garcia and Old & In the Way were turning rock and rollers onto bluegrass and the songs of Peter Rowan, the Stanley Brothers, and Jim and Jesse McReynolds. The aspect of turning people on to music was certainly not limited to bluegrass, where Garcia was concerned. The Jerry Garcia Band was his outlet for a good 20+ years, wherein he’d groove to just about any and everything. Motown, Louis Armstrong, Los Lobos, Allen Toussaint, Irving Berlin, Bob Dylan, Bob Marley, Van Morrison … the stream of tremendous musical taste was just about endless. And, of course, adding his own flair, passionate vocals, and one-of-a-kind guitar to it all made for hundreds of satisfying shows and numerous albums.

Jerry Garcia made music that was loaded with adventure. Improvisation was his nature, always seeking out what was around the bend, never wanting to play the same thing the same way twice. That adventure is what drew so many to him and his music. That adventure lives on, not only eternally in his music, but also through the lives, songs, and good deeds of those he inspires.

Illustration by Zachary Johnson

LISTEN: Gwyneth Moreland, ‘The California Zephyr’

Artist: Gwyneth Moreland

Hometown: Mendocino, CA

Song: “The California Zephyr”

Album: Cider

Release Date: April 21, 2017

Label: Blue Rose Music

In Their Words: “In 2008, I booked a 3,000-mile trip by bus and train from my hometown of Mendocino, California, through the Southwest. With a heavy heart, I began a journey of long rides on the Pacific Surfliner and Southwest Chief, with a return ride from Denver on the famous train, the California Zephyr. During this time, I began to realize that my relationship with my then-boyfriend/bandmate was dissolving. So, yeah: I was heartbroken, torn up, and in desperate need of an adventure.

So, when inspiration from the Carter Family’s “The Cannon Ball Blues” struck while aboard the California Zephyr, I went with it. What came out was not a biographical song, but one that was definitely shaped by the way my heart was feeling and all the tunes floating through my head on that 54-hour ride from Denver. A friend nailed it when he said, ‘You are singing about leaving behind your honey babe, but you’ve got a huge smile on your face!’ And yes, it’s true — I do … now. All those years of searching have led me here to this moment. The train keeps rolling.” — Gwyneth Moreland

Photo credit: Jay Blakesberg

MIXTAPE: Lee Ann Womack’s Country Primer

When we needed an artist to make us a Mixtape of classic country tunes, we turned immediately to Lee Ann Womack … and not just because we love her very, very much, but also because she grew up hanging out in an East Texas radio station while her father played some of the greatest country music ever made. LAW noted that these aren’t, necessarily, her favorite country songs and they don’t go all the way back, but they are certainly a solid representation of the genre’s great past which has absolutely informed its wonderful present.

Johnny Cash — “I Walk the Line”

The ultimate crossover artist, he took country beyond all boundaries. He’s not just one of the greatest country artists, but one of the greatest American artists of all time.

Bill Monroe — “Blue Moon of Kentucky”

He might have been known as the Father of Bluegrass, but music in the country genre was heavily influenced by Bill Monroe. I love — and have borrowed from — the mournful sound of his vocals, the electricity of the harmony vocals, and the drive of the instruments in his music.

The Carter Family — “Wildwood Flower”

Nicknamed the First Family of Country Music, the Carter Family were pioneers of mountain gospel and country music, utilizing harmony vocals in a way that would influence the country genre for many years to come.

Waylon Jennings — “Lonesome, On’ry and Mean”

He had a career as a sideman for Buddy Holly and as a disc jockey in radio before he ever came to Nashvillle to make country records. He was part of the first platinum country album, Wanted: The Outlaws, along with Willie Nelson, Tompall Glaser, and Jessi Colter. To me, Waylon was the epitome of the marriage of rock and country, bringing all of his West Texas vibes to ’70s country.

Tammy Wynette — “Stand by Your Man”

You’d be hard pressed to find someone who isn’t familiar with Tammy and her song “Stand by Your Man.” It’s been a controversy several times over! Her voice is like a broken heart poured directly through stereo speakers and her life seemed like a living, breathing country song.

Loretta Lynn — “Coal Miner’s Daughter”

The ultimate country female singer, she wrote and sang about her life, which reflected so many of the people in rural America and the things they were going through. Listening to her music, one could learn a lot about the times she grew up in, and that’s country music: real life.

Dolly Parton — “Coat of Many Colors”

Her Appalachian roots, so present in her voice and music and, obviously, in the lyrics she wrote. The perfect example of a country girl with bluegrass/mountain influences.

Buck Owens — “Together Again”

From Sherman, Texas, and, along with Merle, created the Bakersfield sound. As is often told, Buck influenced countless other artists in and outside the country genre, not the least of which was the Beatles. I always loved his use of the telecaster and harmonies via Don Rich, and could hear their influences in so many of the country acts that followed.

Merle Haggard — “Okie from Muskogee”

The smoothest and prettiest voice of the male country singers, I always loved Merle for his music and his appreciation of music. I love his playing and especially love his studious approach, pouring over the catalogs of masters like Bob Wills and Jimmie Rodgers — not to mention the blues and jazz music influences you can hear in him. He fascinates me. Along with Buck, they created a whole new country music scene in Bakersfield and refused to play by the rules. I love it.

George Jones — “He Stopped Loving Her Today”

I could do a whole list of just George Jones songs. To me, he surpasses all others because he actually created a new style of singing. Often imitated but never, ever has anyone come close to duplicating. As Gram said, “He’s the king of broken hearts.”

Hank Williams — “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry”

A country boy with so much soul, he transcends any genre and is one of the greatest songwriters in all of music.

Willie Nelson — “Crazy”

An American treasure, Willie is another artist who really transcends all genres, but there’s no mistaking his country upbringing. He puts music first, before any kind of labels or boxes, and he definitely influenced Nashville and Texas music in a huge way and showed that, when it’s honest, country music and country artists can have mass appeal.

Reclaiming Community: A Conversation with Tyler Hughes

In early February, the Empty Bottle Stringband made their debut at the Carter Family Fold in Hiltons, Virginia, a hallowed ground for lovers of old-time and country music. A quartet of old-time musicians based in Johnson City, Tennessee, the Empty Bottle Stringband specializes in the lively, toe-tapping fiddle tunes that fill the floor with dancers at the Carter Fold, and the band is familiar with the musical family who gave the venue its namesake. When Tyler Hughes takes up the autoharp and introduces the Carter Family song, “There’s No Hiding Place Down Here,” the sounding rhythm is closely kin to the style of Mother Maybelle Carter, a living example of the sound that brought Southwest Virginia to the world’s musical attention. Hughes’s performance carries other ties to the cultural ground he’s standing on: in the clear, true tone of his singing, the stories that enrich the music, and the down-home humor that has brought laughter from generations of careworn audiences.

As a solo performer and member of the Empty Bottle Stringband, Hughes has represented Appalachian culture on stages across the eastern United States since his teenage years. Now in his mid-20s, he continues to live, teach banjo, and organize cultural arts projects in his home community of Big Stone Gap, Virginia. Hughes is a graduate of the Old-Time, Bluegrass, and Country Music Studies program at East Tennessee State University and, during his time as a student, he performed extensively with the ETSU Old-Time Pride Band. Whether he is attending a board meeting for a community foundation, calling a square dance, or showing a local kid their first chords on the banjo, there’s a reverence of heritage evident in all of his work. The ties to Hughes's Appalachian heritage are collective — traditions of music and dance which work best when a group will put them to use, not admiring them from a distance, but participating in the present.

Tyler, tell me where you grew up, some of your family’s history there, and how you started to play old-time music.

I grew up in Big Stone Gap, in Southwest Virginia. I grew up in town, but on top of a mountain; we have a really beautiful view of Powell Valley from our front porch. I grew up in the mountains, playing in the woods, and I had some interest in music as a kid, but later in my teen years, I took up music more seriously. My family’s been here for several generations now, and my mom and dad were both raised here in Big Stone. My dad was raised in town and my mom was raised outside of town in Powell Valley in a little holler called Cracker’s Neck, which sounds like a really magical place and it was. My mamaw and papaw lived in Cracker’s Neck, and my papaw still lives there. Both of them were avid country music fans — and so is my mom — so I grew up listening to modern country, '90s country, but I also listened to a lot of older country like George Jones and Loretta Lynn and Dolly Parton. I was taught to appreciate all that. I remember going to my grandparents’ house, and my mamaw would get out her record player and her eight-track tapes and listen to those artists. My grandparents were a big influence on me and they were also big fans of the '90s line dancing craze so, when I was younger, they would take me out to line dances, and I would be part of their line dancing group pretty often.

I started playing music when I was about 12. I’d always had an interest in music — I was in chorus in school and in theater — but I really didn’t have an interest in traditional music until a little bit later, when I started taking guitar lessons. I started taking banjo not too long after that, and I attended a local camp here called Mountain Music School. I attended Mountain Music School in its second year, and it was there that I really got introduced to the region’s music — people like Papa Joe Smiddy — but especially I remember the Whitetop Mountain Band came one day and played for us, and Emily Spencer, who’s a really wonderful banjo player from Southwest Virginia, was one of the leaders of the group. I just remember seeing and hearing her play the banjo and I thought, “That’s what I want to do.” Emily’s playing really struck a chord with me, I guess you could say. At Mountain Music School, I learned how influential Southwest Virginia’s music is on the world’s music. I really had no idea about people like Dock Boggs or the Carter Family until I started going to Mountain Music School and hanging around the folks that helped organize the camp, like Todd Meade and Julie Shepherd-Powell and some other folks.

The Empty Bottle Stringband at the Carter Family Fold. From left: Ryan Nickerson, Tyler Hughes, Kristal Harman, and Stephanie Jeter.

One thing we’ve talked about often is how the women who shaped the music of Southwest Virginia, what a great impact they’ve had on both of us, and I know one woman we really admire and look to as an inspiration is Janette Carter, who established the Carter Family Fold in memory of her parents Sara and A.P. Carter. Why do you connect with Janette’s music and what does her life’s work mean to you?

I, unfortunately, never got to meet Janette, even though I’d been to the Carter Fold several times and played at the Fold, but I didn’t start going until after she had passed away. On one of my first trips to the Carter Fold, I bought Janette’s book, Living with Memories, and read it. I was just so impressed with her because she overcame so much. The Carter Family … the Carters were in no way rich, especially growing up in Poor Valley in Scott County, Virginia … so Janette really rose above the poverty that most people see in that region. She was a radio star as a teen and she came back home, married, settled down to raise her family and went to work at the local school — she was a lunch lady there. She still played. She played the autoharp and guitar and sang songs. She felt so strongly about her family’s influence on music and her father’s music that she wanted to keep this promise to him that she would help carry on the legacy of the Carter Family. She gave up her job and really risked pretty much everything to open their grocery store up as a venue, a concert hall. I think it really says a lot about how brave she was, as a person, because there was no guarantee that opening up a 20-by-20 grocery store and putting chairs in it and asking people to come out and pay to hear music would work, especially in a region that’s impoverished.

I do admire her for that. In an interview I’ve heard with her, Janette said, “One day I was working and I thought, ‘I have some talent and why don’t I use it,’” so she started putting on school programs and traveling with her music a lot. Another woman who has really influenced your work and music is Sue Ella Boatright-Wells; she is part of organizing so much of the region’s community music scene. Tell me about her.

Sue Ella Boatright-Wells is also from Scott County — she lives in Scott County today. She doesn’t play music, but old-time music fans who dig deep have probably heard of her father, Scott Boatright, who was really good friends with the Powers Family and Dock Boggs and the Magic City Trio; Scott played with several bands in the area. Sue Ella grew up with music in the home and, when she took her position at Mountain Empire Community College in Big Stone Gap, she wanted to use that as an outlet to help preserve that music.

Sue Ella has been an influential part of the Home Craft Days festival at Mountain Empire Community College, helping to get local artists and musicians to the campus each October to showcase their art and their music. She is the mastermind behind Mountain Music School, which was such a huge influence on me, and even today, Sue Ella works tirelessly to help support efforts by the Crooked Road and their Youth Music Initiative and the Junior Appalachian Musicians program, which is now in Wise County. She works very hard to see that those programs succeed and are able to expose children to the music, especially our youth here that probably didn’t grow up with this music. As in any rural area, money never flows freely in the form of grants or government funding for the arts, so it’s sometimes a pretty difficult fight to find funding and to find ways to make these programs go, but Sue Ella never backs down. She’s always got a plan and she always works extremely hard to see that these programs do happen and that they happen to the best of their ability.

I’m very, very lucky to call Sue Ella a friend. I’ve looked up to her for a long time and she was incredibly encouraging to me, coming along as a banjo player. After a few years of attending Mountain Music School, she asked me to come on and be an instructor there, and today I co-direct the program and try to do a lot of work with Sue Ella to see that these youth music programs happen. I do try to model my work after Sue Ella’s.

I guess most people wouldn’t think that organizing music or organizing dance and art, especially in the mountains … people probably don’t put the same value on that as maybe somebody who organizes a food drive or a fundraiser to build a park or whatever. They probably don’t see the same value in promoting the arts because that seems intangible. But advocating for local music and arts is such an important thing to do to build community. Unfortunately, we live in a time where technology, as great as it is, is diminishing our abilities to be together as communities — just humans, one-on-one — and to share experiences like music. That’s why I feel that it’s so important to continue to organize events and programs, especially for youth, to show that this music has continually brought people together for years and years and, hopefully, will continue to bring.

Tyler Hughes demonstrating flatfoot dancing at the Papa Joe Smiddy Festival. Photo by Dan Boner.

Speaking of community and music bringing people together … you’re a square dance caller and a prize-winning flatfoot dancer, so I want to hear about your background in dance.

I started learning to dance not too long after I started learning the banjo. Probably the first person that ever showed me anything was Anndrena Belcher; she was living in Scott County at the time and she’s also someone that I look up to. Anndrena really does see the true value of our own personal stories and songs, and she’s a really wonderful musician and writer and storyteller and dancer. She was the first person to ever show me any steps; I was lucky, I got to do several workshops with her around Wise County where we went out and taught other students to dance.

Anndrena teaches dance not just to preserve or carry on the tradition, but simply to do what any kind of art is created for: self-expression. I thought that was very important and something that we shouldn’t lose when we are passing on these cultural traditions. So often in the region, we just talk about how endangered our way of life can be, and how some tunes and music aren’t getting played as much as they once were, and some dances aren’t being danced as much as they once were. It is important to preserve these arts for the historical aspect, but also for the self-expression and the social aspect. For a long time, one of my very best friends lived here in Big Stone Gap, Julie Shepherd-Powell, who’s a really wonderful banjo player and also an award-winning flatfoot dancer. She taught me a whole lot and she spent a lot of time with me at some workshops and, just on the side, teaching me different dance moves.

Julie Shepherd-Powell is also a fine square dance caller, and I know not too long ago you hosted a square dance in Big Stone Gap, and it was one of the first that had been held there in quite a while.

I started to learn to call square dances about two years ago. For a long time, I was head of a contra dance organization at East Tennessee State University, where I went to college. Along the way, we were having a lot of fun with contra, but we wanted to experiment with square dances because square dances were much more closely associated with old-time music, the music we were playing in the program. We looked around and we only knew a handful of square dance callers, and we found out that there was no young person within our immediate crowd calling square dances in Johnson City. So I took it upon myself to try to learn some and, today, I’ve probably mastered about eight to 10 dances. In December, I pulled together several organizations — the Big Stone Gap Parks and Recreation Department, a couple local business sponsors, Auto World, and the local grocery chain Food City all pitched in and several community members baked goods and food, and we all met here at an old Girl Scouts cabin. Some wonderful friends of mine, Bill and the Belles, came over and played the music and we had the dance and it was successful. The dance was well-attended: People were really receptive and supportive. Dance is a very important tool to get people together to socialize and share experiences about what’s happening in their community.

While we’re talking about Wise County, another woman from that area that you and I both admire is Kate Peters Sturgill, the great songwriter. Tell me why you sing her songs.

Kate was from Josephine, Virginia, a little coal camp just below Norton out in the county. She was a wonderful guitar player and singer but, more than anything, I love her writing. I’ve always said she was one of the most poetic writers from the region that I’ve ever come across. She really puts her passion for her home community into her writing — songs like “My Stone Mountain Home,” which I perform now. Kate is not an incredibly well-known artist — most people, if they’ve ever heard one of Kate’s songs, it’s probably her best-known gospel tune, “Deep Settled Peace” — but she wrote a whole handful of beautiful songs and many of them deal with our home county. She wrote “My Stone Mountain Home” about the mountain chain that runs down Powell Valley and between Appalachia, Virginia. She also wrote about the Trail of the Lonesome Pine, which has a lot of significance here. The book and the outdoor drama by that title, written by John Fox Jr., were based loosely on local people and events here in Big Stone Gap. The context still exists to have Kate’s songs sung and played here.

The Empty Bottle Stringband playing for the extras party for the film Big Stone Gap at the Trail of the Lonesome Pine outdoor drama. Photo by Sam Gleaves.

I really enjoy the way that you use humor on stage when you perform. That’s a real tradition in country music. Why do you think it’s important to be funny and entertain as you present this music?

I think that often, especially as old-time musicians and musicians who want to preserve early country music in the form it was created in, we sometimes forget that we’re pretty much the only ones who are thinking so deeply about the historical context of the way the instruments were played or even what the songs were saying. When we take those out to a wider audience — unless you are playing for a special audience that is there to have this historical significance explained to them — people are still coming because it’s music, and music is fun and entertaining. This music is light-hearted or it can be really deep and emotional, and I think people want to feel all of that.

I think the best way we can present the music, truly, is putting it on as a show, because that’s the way it’s always been done. People in the 1920s weren’t playing “Cottoneyed Joe” or “Turkey in the Straw” to historically preserve the tune from the way it was played in the 1860s. They were thinking, “This is fun, this is entertaining.” I don’t think that’s anything we should forget, especially if we want to bring old-time music to a wider audience. It doesn’t have to be as if we’re presenting a piece from a museum.

I love to hear you tell a good June Carter joke, but in closing, I know another female musician and songwriter we really admire is Ola Belle Reed, and she once said in an interview, “We all need each other, whether we know it or not.” I think that speaks so much to what community organizing is about and what old-time music is about. Being a community organizer and someone who has put old-time music at the center of their life, can you talk about that?

I think that’s definitely true. Unfortunately, we still live in a world where stereotypes get placed on everybody. We all do it, whether we mean to or not. When most audiences think of old-time music, they probably have in mind a hillbilly character or, perhaps, only white men playing it or it being associated heavily with Protestant faiths — the stereotypical images of Appalachia that are often portrayed. Often, old-time music probably evokes those same stereotypes to people outside the region, but the beautiful thing is that old-time music is just as diverse as the region itself and, as anywhere else in the country — or the world, for that matter.

Whether it be old-time music or pop music, music transcends the barriers that society places on all of us. It really doesn’t matter whether you’re rich or poor or black or white or gay or straight; however you identify, music can touch us all and affect us all. If we aren’t brought together through some type of connecting bridge like music or dance or community events, then we may never know that we’re sharing the same experiences and how important it is — that we’re not alone. Often, I think we get bogged down as individuals in our lives but, by coming together through art, we find many others who are sharing those same feelings and can relate to us. When we relate to each other, there’s empowerment and there’s a healthier sense of community.

Lede photo by Kristen Bearfield.

Sam Gleaves is a folk singer and songwriter from Southwest Virginia. His latest record, Ain’t We Brothers, is made up of stories in song from contemporary Appalachia, produced by Cathy Fink.

Counsel of Elders: Ralph Stanley on Being Yourself

The term living legend is thrown around a lot these days. But bluegrass icon Dr. Ralph Stanley deserves the title. Over the past six decades, he has become one of the most influential artists of all time. His early brother group helped define the high lonesome sound that we now associate with bluegrass singing, and his work with the Clinch Mountain Boys has spread the gospel of bluegrass to new generations since 1946.

Stanley received an honorary doctorate from Lincoln Memorial University in 1984, and he’s been affectionately referred to as Dr. Ralph Stanley ever since. In 2002, he received his first Grammy for his solo version of “O Death” from the film O Brother, Where Art Thou. It introduced him to a new audience, and introduced a new audience to bluegrass. He is a true legend, in every sense of the word.

Dr. Stanley, you have had a long and successful career, much more so than the typical musician. Looking back on it, is there anything that you now know that you wish you knew when you were starting out? Is there something that you learned the hard way that could have been avoided with the proper advice?

No, not really, I don't think. It was hard, when I first started out, but I'm thankful all the hard work paid off.

Did you have any mentors when you were starting out? Can you share a piece of advice they gave you?

I used to listen to the Carter Family, Mainers Mountaineers, and the Grand Ole Opry. I never met any of those people til later. I just enjoyed their music.

Is there any other advice that you'd like to share with the next generation of musicians?

My advice would be, always be yourself. Never try to copy anybody else's sound. Come up with your own style of music and work hard at it.

Correction: The original version of this article mistakenly cited Dr. Stanley as a member of Bill Monroe’s Bluegrass Boys. BGS regrets the error.

A Trip to Bristol: The Birthplace of Country Music

Nestled in the foothills of the Appalachian mountains 300 miles east of Nashville, the Virginia-Tennessee border city of Bristol has long been widely known as “The Birthplace of Country Music” — the mythical small town where the “big bang of country music,” as music historian Nolan Porterfield first called it in 1988, took place during 10 apocryphal days during the summer of 1927.

Due to its relative proximity to varying regions, from Asheville, NC, to the Virginia Blue Ridge Mountains to the Clinch Mountain ridge in Kentucky, the town of Bristol was where New York-based talent scout Ralph Peer set up an open audition in order to attract regional Southern talent to the fast-growing recording industry of the pre-Depression mid-1920s. Among the dozens of artists that showed up for the open call during that summer were Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family.

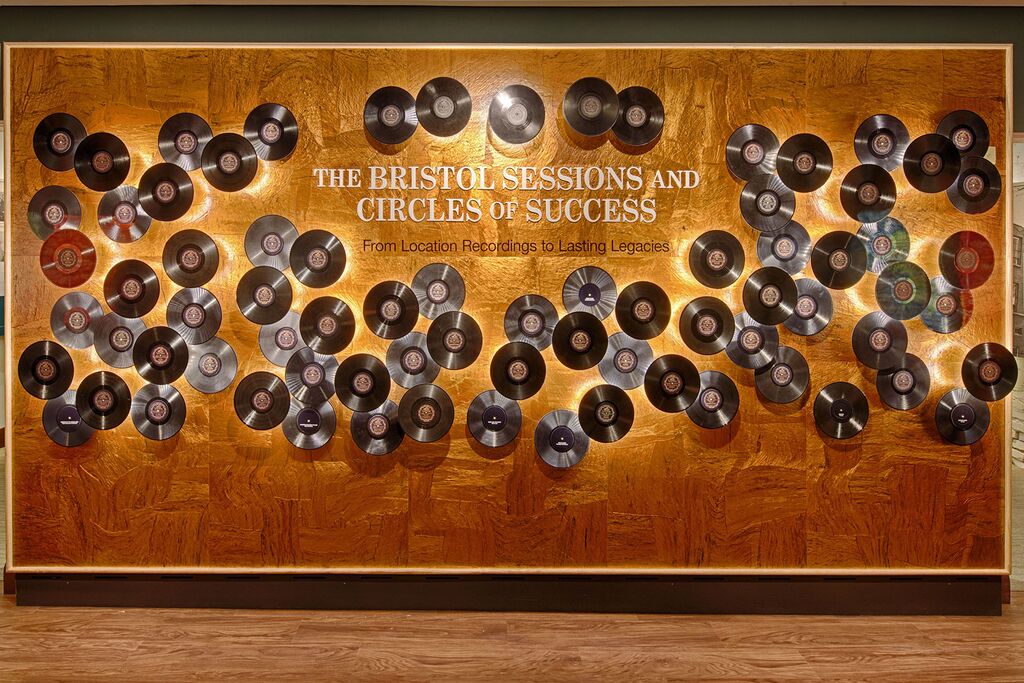

Nearly 90 years after the historic ‘27 sessions, the Birthplace of Country Music Museum opened in Bristol in the summer of 2014. The museum, which earned immediate affiliation with the Smithsonian, cost $11 million to build and is surprisingly expansive, devoted not only to the history of the ‘27 Bristol Sessions and the early roots of country and bluegrass music, but also to the history of the town of Bristol and the region at-large.

Here are some of the museum's highlights:

The Original ‘27 Newspaper Ad Announcing the 10-Day Audition

“Don’t deny the sheer joy of Orthophonic music,” begins the advertisement announcing Ralph Peer’s open audition. That phrase, Orthophonic Joy, was used as the title to a new album released earlier this year featuring artists Ashley Monroe, Vince Gill, Emmylou Harris, and Dolly Parton and Marty Stuart remaking some of the most famous Bristol Sessions material. “The Victor Co. will have a recording machine in Bristol for 10 days beginning Monday to record records,” reads the plainspoken ad. “Inquire at our store.”

WBCM Studio

One interesting facet of the museum is that it also functions as a fully operational contemporary radio station. WBCM Bristol Radio, an FM station that also be found online, plays a selection of bluegrass, roots, country, and old-time traditional music, and hosts a regular array of live studio performances and modern-day Radio Bristol sessions.

Recording Your Own Bristol Session

One of the silliest, most entertaining aspects of the museum is a recording booth where you sing your vocals over newly recorded instrumental versions of several original Bristol session tunes. You can even lay down an earth-shattering rendition of the Carter Family’s “Single Girl, Married Girl.”

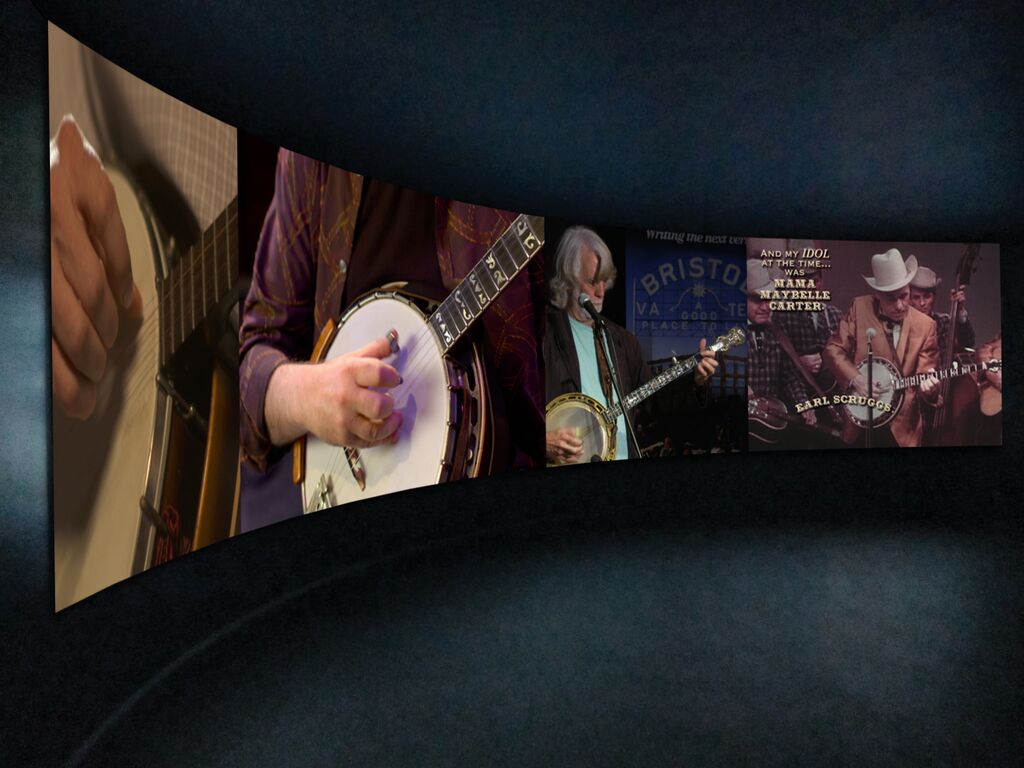

Will The Circle Be Unbroken Short Film Immersion Theater

Toward the end of the museum tour, there’s a short film that is functionally an audio collage of countless different recordings of the spiritual “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.” In the film, the song is performed by everyone from Faith Hill to Mavis Staples to Spirit Family Reunion and the Black Lillies. The film is, perhaps, the best example the museum has to offer of the wide-ranging, ongoing influence the original Bristol Sessions still have on music in the 21st century.

Johnny Cash’s Signed Guitar

Though his relationship to the central focus of the museum is arguably tangential, Johnny Cash forever became a part of Bristol’s musical story when he married June Carter, the daughter of founding Carter Family member Maybelle Carter, in 1968. One of the museum’s most star-studded artifacts is Cash’s Martin guitar from that very year. In addition to Cash and Carter, other country legends, including Bill Monroe, Waylon Jennings, and George Jones, have signed the guitar.

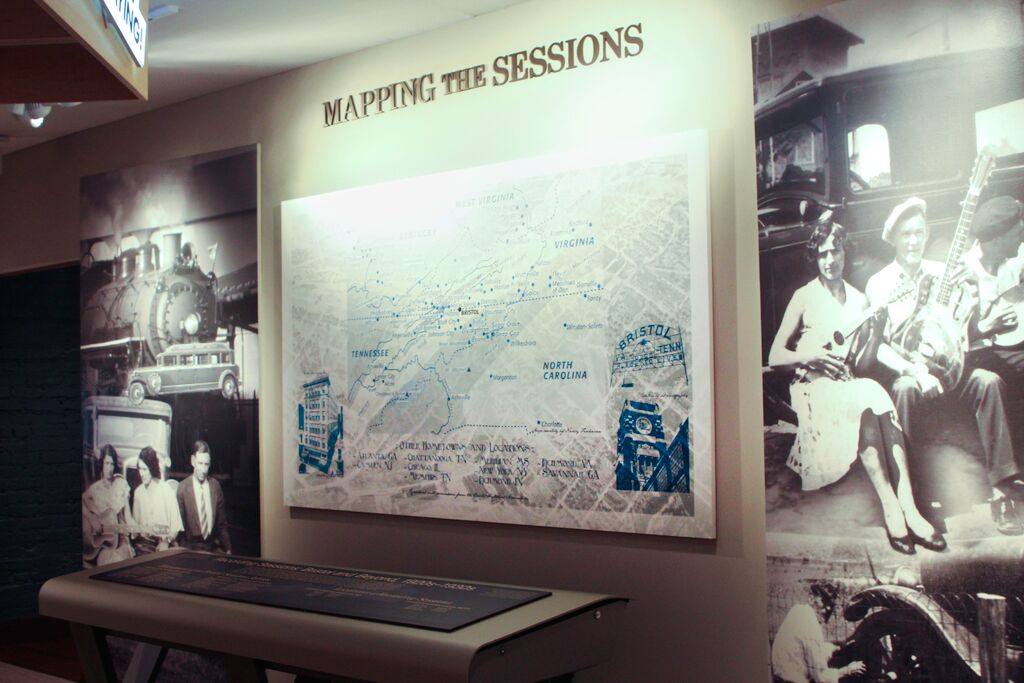

Mapping the Sessions

The museum nicely highlights the early 20th century music of not only Bristol, but, necessarily, its plentiful surrounding areas. One panel notes the individual home towns of each performer at the original 27 sessions who came from at least five different states, from Mississippi to West Virginia.

Segregating the Bristol Sessions

The museum does a particularly good job addressing the racial hypocrisy and discriminatory practices of the recording industry during the 1920s. Blues music recorded in Bristol by white artists like Henry Whitter were marketed as hillbilly records to mainstream white audiences, while similar-sounding recordings by blues player El Watson were marketed and distributed as “race records” to black audiences. Kudos, too, to the museum gift shop for selling Segregating Sound, Karl Hagstrom Miller’s fantastic book that outlines how the early 20th-century recording industry so often imposed harsh racial boundaries and segregations on the musicians and artists they recorded.

Bound to Bristol

John Carter Cash narrates a 20-minute film near the beginning of the museum tour called Bound to Bristol. The piece gives a fairly comprehensive overview of the story behind Peer’s recording sessions and touches on the importance and centrality to early country music of Ernest Stoneman, the hillbilly singer who encouraged Peer to record in Bristol.

The Hill Billies

One of the most informative panels of the museum is the one that explains the derivation of the term hillbilly as a way of denoting country/white rural music during the first half of the 20th century. Peer was recording a string band in 1925 and when he asked them for their name. They shrugged and said, “the Hill Billies.” For the next 20 years, country music would be marketed, distributed, and commercialized as “hillbilly” music.

The Birthplace of Country Music Museum is currently hosting an expansive special exhibit on the career and life of pioneering American roots singer Tennessee Ernie Ford. The exhibit runs until February, 2016.