[Editor’s note: Read part one of Neil’s Memoir on the First Canadian Bluegrass Festival here.]

On Wednesday, August 2, 1972, after an overnight ferry voyage, I arrived in North Sydney, Nova Scotia. A four-hour drive brought me to Fred and Audrey Isenor’s mobile home in Lantz, 50 km (30 miles) north of Halifax. It was just after 7 pm, and they already had company, including gospel singer Lloyd Boyd, known as “The Radio Ranger,” and Charlie Fullerton, a dobroist and bassist whose sound system was to be used at the Jamboree.

Other friends of Fred’s dropped in that evening – men and women active in the local country music scene who shared his interest in bluegrass. I was the center of attention, the imported expert on the eve of Nova Scotia’s first homegrown bluegrass event. In my diary I noted:

Immediately I was quizzed on my knowledge of instruments, principally, D- series 45 style Martins but other things as well. Fred’s F-5 pulled out, my F-4 and Mastertone looked at.

Owning a prewar Gibson or Martin was a mark of serious interest in bluegrass. The big fancy Martin D-45 was the top of that guitar-maker’s line. Only 90-some were made from the early ‘30s to 1942; these were owned by famous country stars, including bluegrass great Red Smiley. In the late ‘60s Martin began making the D-45 again. Lloyd had one.

I noted another visitor:

Carl Dalrymple, a C&W bassist and guitarist about to go on the road with his sister-in-law [Joyce Seamone] who has a number one Canadian Country hit, “Testing, One, Two, Three,” came [by]. He’s a D-45 owner, too.

Carl’s son Gary, then three years old, already introduced by his father to bluegrass, became one of the second generation of musicians nurtured at the Festival which grew out of the coming Friday’s Jamboree. In 1993 Gary, a mandolinist, joined The Spinney Brothers, one of Nova Scotia’s most successful bands. I was honored to have them play during my 2014 induction into IBMA’s Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame.

By the early ‘70s, bluegrass in the Maritimes had been embraced by the young, working-class, rural country musicians who formed most of the “spread out” Canadian bluegrass community Vic Mullen had told me about. This night at the Isenors’ was my introduction to a new world of musical friends and acquaintances.

As the evening wore on, the focus shifted from instruments to music making. We jammed; I noted:

We played lots of gospel songs, few bluegrass standards, I did requests for Peggy [Warner, a budding banjo picker]. Tempos were slow generally.

This was not like bluegrass jams I’d experienced during the 1960s working and hanging out at Bean Blossom. In a sense, it was a step back in time for me. In my college years, fifteen years before, I’d first learned about bluegrass through recordings. It was a distant thing.

Then I moved to Indiana, met Monroe at Bean Blossom. By the time I moved to Canada the festival movement had attracted new audiences. Mid-’60s youth had embraced folk music; that drew some of them into bluegrass — the beginning of a process of gentrification that I’ve written about in Bluegrass Generation (pp.240-42). In 1972, this hadn’t happened yet in Atlantic Canada.

The next afternoon, Thursday the 3rd, Fred took me into Halifax. Knowing I was a professor of folklore, he wanted to show me a new shop in town, the Halifax Folklore Centre. He introduced me to the owners, the Dorwards, who, I noted:

Looked at my F4 (fret wire needed, if they are to do a fret job). I got the J&J instrumental LP. Lots of blues records. Fred and Tom Dorward, the owner, get on well.

I don’t recall much talk about the Jamboree. Months later, Fred confided to me that in promoting the event, they’d failed to connect with the Halifax university students who were into folk music. Dorward would play a role in that regard at the Festival, which grew out of the Jamboree. Next, I noted:

…we went to CBC to see about placing ads, and then to an electronics distributor for a mike.

Later I added to this note:

…a local fiddler who was supposed to play in Friday’s festival — Russ Topple — had unexpectedly gone to the U.S. (Wheeling) so when we stopped at the CBC … Fred put my name on the ad as visiting banjo picker. Everyone knows that I worked with Monroe, most think that means as a banjo picker. Lots of questions about the banjo (“old Mastertone”) etc.

After supper we went to farmer John Moxom’s place out in the country at Hardwoodlands, the festival site, about 14 km (8.7 mi) east of Lantz, to help Charlie Fullerton set up his sound system. I noted:

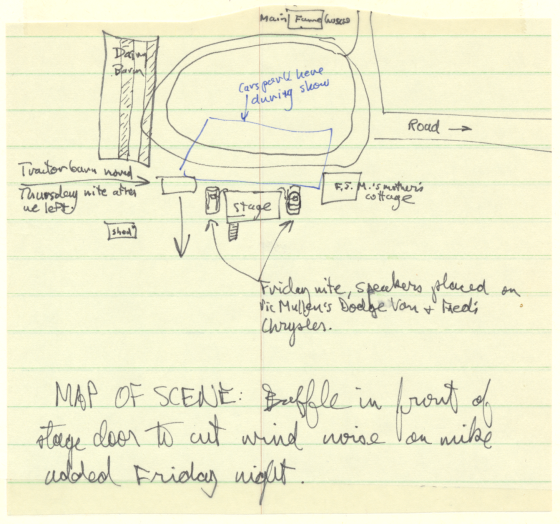

Farmer J.M. has built outdoor covered stage about the size of and dimensions of that at Roanoke. On 4 posts 6’ high; 18’x10’ floor with covered sides (except for the last 4’ at front). Roof slopes from 10’ at the front to 7’ at the back. Rough steps off the left corner rear. We end up setting speakers on Fred’s ’66 Chrysler roof beside the stage for separation. See map of festival site on the following page.

The evening ended with a rehearsal at the home of Don and Joyce Peck, Fred’s bandmates. I noted:

Charlie subbed on bass for Fred’s partner (in his Lantz music store, Country Music Sales), Bruce Beeler, who works as a chef on the CN RR.

After dinner the next day (Friday the 4th), Fred and I returned to his home after visiting more of his musical friends, to find The County Line Bluegrass Boys had arrived. They would be playing at Jamboree that evening. They were from Lunenburg County, down on Nova Scotia’s South Shore. I noted:

The mandolin player and the banjo player (Mel Sarty) are the central figures in the group — first got into Bluegrass when they were 11-12 years old in the early sixties, when a relative bought the Bluegrass Gentlemen LP by chance. Have learned entirely by records. … They do quite a bit of four-part singing.

Vic Mullen, Nova Scotia’s best-known bluegrass musician, was the emcee that evening at the Jamboree. The audience was mainly in cars, parked in front of the stage. Applause came in the form of honks and flashed lights. Three Nova Scotia bands appeared.

The Pecks with Fred and Bruce on bass opened. Vic and I helped add a bluegrass touch to their sound with fiddle and banjo. A number of other singers and pickers joined us for guest appearances. Next came the County Line Bluegrass Boys.

The Boutilier Brothers closed the show. They came from a musical family; their grandfather was a well-known old-time fiddler in the region, and the two oldest brothers, Bill and Larry, began their professional career with their father, also a noted fiddler. They were inducted into the Nova Scotia Country Music Hall of Fame in 1999.

By the early 1960s they were singing brother duets and appearing with Vic Mullen on banjo. With the help of Mullen, they made four LPs (all had “Bluegrass” in their title) on the Rodeo label between 1963 and 1967, by which time a third brother, Ken, had replaced Vic on banjo. The brothers had retired several years before, but came out of retirement specially for the Jamboree.

When Fred and Vic surveyed the results of the Jamboree, they decided to try another the following year. This time they would announce it as “the second annual BLUEGRASS FESTIVAL at Hardwoodlands, N.S., July 27, 1973.” The Boutiliers and the Country Line Bluegrass Boys appeared again; more widely advertised, it was successful and drew enough bluegrass enthusiasts that in 1974 Fred and Vic brought Tom Dorward into their planning and began working on a two-day event.

For the next five years, I traveled to the Festival annually from Newfoundland to help Fred and the gang, running instrumental workshops, emceeing, and appearing with our St. John’s-based band, Crooked Stovepipe.

As the Festival took off, young musicians began appearing. Eventually a fourth generation of Boutiliers became involved. In the 1980s these young pickers added Vic Mullen to their band, and, with his encouragement, took on his old band name, calling themselves Birch Mountain Bluegrass Band. In 2001, 2002, and 2004 they won the East Coast Music Association’s “Bluegrass Album of the Year” award.

Another second-generation band developed out of the County Line Bluegrass Boys. In 1973 banjoist Mel Sarty’s brother Gordon joined the band as bassist and in the 1980s he and his three daughters created a new band, Exit 13. Lead vocalist, songwriter, and banjoist Elaine Sarty fronted the group. They won the ECMA “Bluegrass Album of the Year” in 1997 and 1998. Here’s a profile of the band that appeared in the ‘90s on a national prime time CBC show, “On The Road Again.“

This, of course, was all to come! I knew nothing of the Jamboree’s bluegrass festival future when I left the Isenor home on Saturday August 5, 1972, continuing my research trip. Heading west on the Trans-Canada Highway, a half-day’s drive brought me to Woodstock, New Brunwick, near the Maine border. There I visited a student and her family who’d invited me to see the Don Messer Jubilee at Old Home Week, Woodstock’s annual fair.

The event was held in a large building in Connell Park, the fair site. It had three components: the Jubilee concert, a fiddle contest, and a dance.

The concert followed the format of Messer’s television broadcasts, with fiddle tunes prominently featured along with songs by the band’s remaining vocalist Marg Osburne. Her singing partner, Charlie Chamberlain, had died less than a month before. This was one of the Jubilee’s last public performances; Messer would pass in March 1973.

The fiddle contest, which Messer judged, was won by Mac Brogan, a fiddler from Chipman, NB. Here’s a sample of his fiddling, very much in the Don Messer style, from his 1984 album:

Finally, chairs were cleared away and Messer and the Jubilee orchestra played for dancers. Although Messer continued on the fiddle, several of the other musicians switched to wind instruments. The music was mainly a sentimental reprise of popular songs from the big band era that they’d played for dancers during their salad days in the ’40s and ’50s.

After the dance I introduced myself to Mac Brogan, telling him I was interested in researching old-time and country music in Canada and asking if he would be willing to talk to me some time for an interview. He consented and gave me his address. It would be over a year before I’d have time to do the interview, but this, along with my conversations with Fred and Vic, marked the start of what would become a decade of studying the connections between country and folk music in the Maritimes.

On Monday the 7th I was off again, heading into New England, en route to southern bluegrass scenes.

Rosenberg is an author, scholar, historian, banjo player, Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame inductee, and co-chair of the IBMA Foundation’s Arnold Shultz Fund.

Photo of Neil V. Rosenberg by Terri Thomson Rosenberg, all other photos by Neil V. Rosenberg.

Edited by Justin Hiltner