Over decades, Janis Ian’s career has risen and fallen and risen again. At 13, she performed at a folk showcase seated next to Tom Paxton. “Society’s Child,” a song she wrote soon after and recorded in 1965, earned her national fame – and death threats. But by the time she was 20, the music industry had written her off as a one-hit wonder. She fought depression and self-doubt for years before the songs “Jesse,” “Stars,” and ultimately “At Seventeen” put her back in the international spotlight.

She received a Grammy Award in 1975 for “At Seventeen” and another for her 2012 audio recording of her biography, Society’s Child. Her songs have been covered by a host of stars, ranging from Nina Simone to Amy Grant to Joan Baez. Yet over the years, she endured a disastrous and abusive marriage. Embezzlement by a long-trusted money manager left her indentured to the IRS. She spent years playing to sold-out overseas audiences without any U.S. airplay.

Nevertheless, she persisted. Today, she has a legacy of 25 albums, countless industry awards, her own record label and a long, happy marriage. Always an activist, she founded The Pearl Foundation to support older students’ higher education goals. In 2020, she started the Better Times Project to help out-of-work musicians during the pandemic.

Now, at age 70, Ian has released her last studio album, The Light at the End of the Line, joined by a stunning array of musicians. After years in the public eye, Ian long ago abandoned any pretense. And she speaks with warm gratitude of the musicians who helped her with her recording, as well as the freedom she has to produce what she considers the best album she has ever made.

“I love that this album has so many different genres. I love that there are people like Sam Bush and Vince Gill on it. And at the same time, they’re working with people like Diane Schuur,” she tells BGS. “I love the breadth of it, and I hope that other people do. I think that as a result of radio and record companies needing genres, we have become very genre-fied. Everything is a contest, and everything’s got to be slotted right now into its own pigeonhole. And I’m very, very happy that this album tries to avoid that.”

BGS: After 15 years, what inspired you to produce an album now?

Ian: I have had a rotating list of about 10 songs that I thought would be good for an album. I wanted my next album after Folk is the New Black to be absolutely song-oriented, with the best songs I could possibly contribute. I set a pretty high standard. I wanted to match or beat songs like “Jesse.” And that took a while. Then one day I looked up at the list, and I thought, oh, my gosh, I’ve got 16 songs here. And I think I’ve got 11 or 12 that would work.

I’ve often wondered, after somebody writes a musical melody like “Jesse,” if one gets to say, “that’s enough.”

But you always want to equal or better what you’ve done. I think especially as you get older, and you realize that the contest is not between you and a bunch of other people; that the contest is between you and what you’ve done. You become motivated by different things, and you’re still motivated. Part of being an artist is just that drive.

A release says you “took risks, both in lyrics and production techniques.” Can you talk about that?

I think in a song like “Resist,” talking about things like female genital mutilation is a risk. Using words like ‘crap’ is a risk in the kind of genres I work with. I think taking something like “Swannanoa” and making it sound like it’s been around for the last 200 years is a different kind of risk. Certainly, taking all those different musicians on “Better Times Will Come” and saying to each of them, “Okay, I want a step-out performance, like you’re with the Dorsey band, and you’re standing up and taking your solo from the very first note,” that’s a risk, because you never know what you’re going to get.

And I think putting together an album that only concerns itself with what are the best songs rather than what are commercial songs or what’s going to make radio happy, what’s going to make folk listeners happy — those are all risks. Those are all things that I’m not sure I could have done when I was younger.

Did having your own label free you up to do this?

It’s a combination of not being with a major label and not having to deal with the constant pressure of you need to do this, you need to do that, you need to look like this, you need to be there. Not being with a major label is a huge advantage for somebody like me. Plus, you actually get to earn a living. You actually get to keep part of what you make.

There are disadvantages, too. Without a major label, I wouldn’t have an international career. Without a major label, the people who heard me at 17 would not have heard me. So, it’s a plus/minus. I started the record company because I was more interested in making albums than making singles. At the time, that was a pretty bold thing to do. Oh, God, the amount of times I heard “singles drive the album,” even though album sales were booming and single sales were falling.

What did you mean when you said, “I realized that this album has an arc”?

As I started looking at the songs and the sequencing, it very clearly had an arc to me. From the statement “I’m Still Standing,” which is at once a statement of intent and a slap in the face to everybody who’s ever asked me whether I’m still making music, just because I’m not on television. But following that with “Resist” brought it full circle back to “Society’s Child.” And you’re standing there, and you’re involved in the refugee issue and the feeling that you will never again get to see your beloved home again. You’re dealing with friends who are losing children. You’re dealing with friends whose children are trans. Or you’re dealing with the fallout from the myth of the artist as a crazy person, and then having known Nina (Simone) who was a crazy person — until you get really worn out. And all of a sudden you go, “Take this off me, I can’t cope anymore.”

And then you move from that back to being a writer and thinking about good days in New York, and how wonderful it was when you were really young and the conga players in Central Park during the summer, to realizing that you’re in the last part of your life. So, you try to look at it not as the end of the line but that there’s a light coming. And “The Light at the End of the Line” is really a love song to my audience, because that’s how I feel about them. And then following it with “Better Times Will Come Again,” the Covid arc, clinging to hope like a drowning person clings to a stick. And then it all goes to hell, then it all comes back. And then it winds up with a big giant question mark, which really is what life is about anyway, isn’t it?

You have always been an avid learner of instruments. Do you feel you have to still practice?

Before a tour, absolutely. That’s part of the job, whether you’re with a band or not. I go out solo, which in some ways is a lot easier, but in some ways is a lot more difficult because it really requires that you be there and present and accountable every moment of the show. There’s nobody to hide behind. The older you get, the less fascinating you find yourself. Along with that there’s also the understanding that it’s great to play a lot of instruments and write a lot of songs, but it’s even better to play one instrument really well and write one really good song.

You have been writing science fiction. What is it about that genre that attracts you?

I think part of it is that I bore easily. I don’t mean that to sound snotty. But I do. Science fiction in general is not boring. It’s sometimes tedious, but not boring. I grew up on it. I think that it’s a lot like jazz. It’s the writing of possibilities. And that’s always more intriguing to me than the writing of what is. I think we tend to forget that Alice in Wonderland is science fiction. Nobody has a problem with Alice in Wonderland. Well, they do. But what do they know! Winnie the Pooh? I mean, how science fiction can you get? Here’s a talking bear. Cool! It’s that it’s a literature of possibilities that I like.

Are you continuing to write prose?

I’ve had nine short stories published. That’s nice, because as my wife pointed out, nobody is going to risk their reputation as an editor on some story that sucks. So, I have to believe that the stories are okay. And each one’s a little better than the last. But it is something I want to do more of. And I’m not one of those people who can do things like that in between 500 other things. Running three businesses—running a record company and a publishing company and a touring company—takes up a lot of time. I don’t remember the last time I had a full day off email. That’s all part of what I’m looking forward to at the end of next year.

Are you still running The Pearl Foundation?

We are, but we’re closing it as of the end of this year (2021). We’ve run it now for 22 years. And we’ve given away $1,300,000 in endowments. It will continue at the schools that have the endowments. But my wife and I have done all the fulfillment and all of the web work and all of the talking about it and performances and all of the begging and scratching. So, it’s time to start divesting ourselves of things that take up our time. I think $1,300,000 is pretty extraordinary. We’ve done that with no help, except from the fan base who contributed their time and their talents and their money. So, it’s a good time to close. You go out a hero.

We grew up in optimistic times, and yet at this stage in our lives, we see that we haven’t gotten any farther than perhaps the Civil War. Is that what “Better Times” was about?

But I think we have gone further. As a gay person, I can’t be lobotomized against my will for being gay. I can get married. It’s not legal to segregate. It’s not acceptable in most places. Yeah, there’s always going to be assholes. There’s always going to be jerks. There’s always going to be people who wish that it was like it was 200 years ago, forgetting that 200 years ago, women wouldn’t have been allowed to own property. I think we’ve come some of the way. And I think we have to hang on to that. We have to remember that the pendulum always swings hard one way or another before it rights itself.

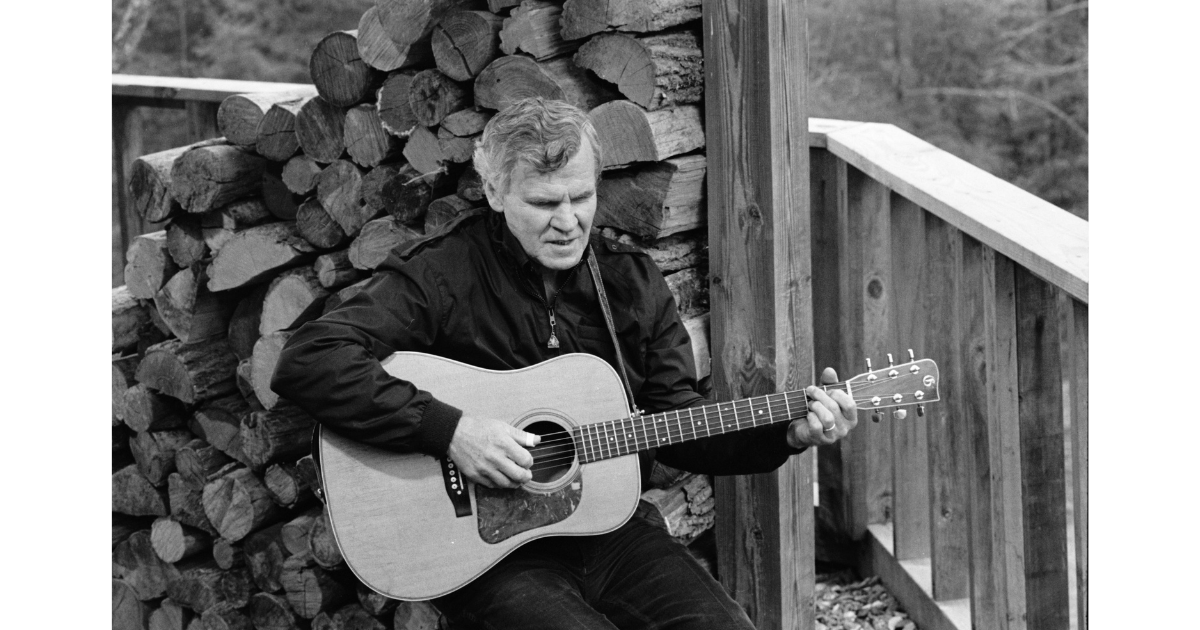

Photo Credit: Lloyd Baggs