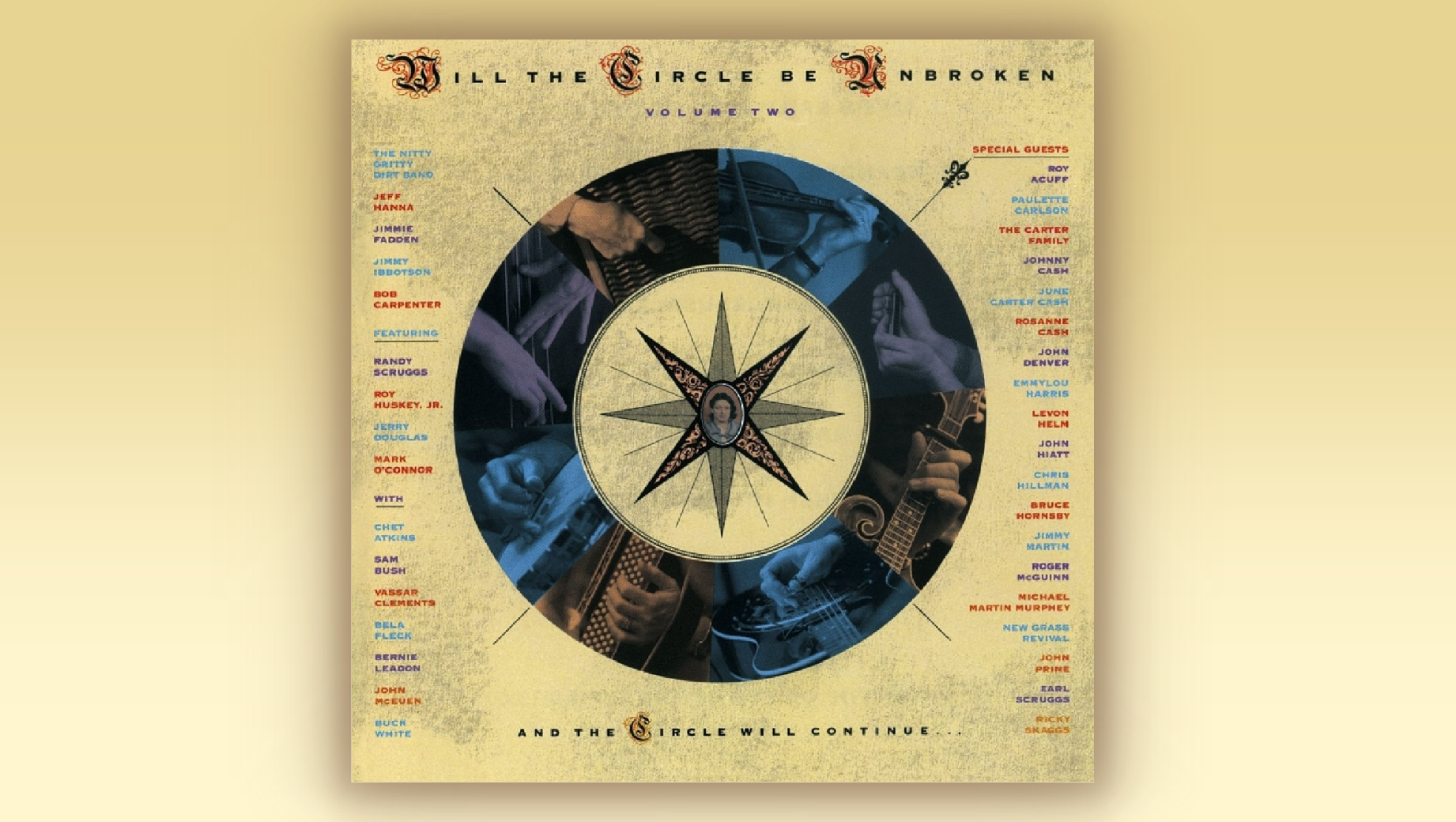

What started as a music video concept for the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band evolved into a 1989 full-length film documenting the all-star recording sessions for Will the Circle Be Unbroken, Volume Two. Nitty Gritty Dirt Band co-founder Jeff Hanna will present a rare screening of clips from The Making of Will the Circle Be Unbroken, Volume Two at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum on September 11 at 11 a.m., during AmericanaFest.

Hanna will be joined by bluegrass virtuoso Sam Bush, who appears in the film and on the album with New Grass Revival. Craig Shelburne, managing editor of the Bluegrass Situation, will moderate.

Produced by Joanne Gardner Lowell and Rosanne Cash, the film captures the band in the studio recording their groundbreaking project. Select clips will show performances by Johnny and June Carter Cash; Jerry Douglas; Emmylou Harris; Bruce Hornsby; Jimmy Martin; New Grass Revival; John Prine; Earl Scruggs; Randy Scruggs; Ricky Skaggs; and others. Will the Circle be Unbroken, Volume Two won three Grammy Awards as well as the 1989 CMA award for the Album of the Year.

Three decades after its release, Joanne Gardner Lowell offered some keen perspective on the film through an email interview with the Bluegrass Situation.

BGS: What was it about the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and this project that made it a compelling film subject for you?

JGL: ACME Pictures was contracted to make a video for the title track. This is pretty common. We signed the contract and when I asked what day during the multi-week schedule this song would be done, Jeff said, “All of them.” When I realized we would need to go to the studio every day for weeks to get this song, it seemed obvious we should shoot the whole experience — so we did.

How would you describe the mood, or the vibe, in the room during these sessions?

It was joyful in the studio. Each day the musicians came so ready to create and collaborate. We were honored to be in the room with it all. Being live made everyone really stay on top of their game. It felt like a family reunion on many days, and there was always a lot of humor and laughter. Our primary director, Bill Pope, captured so much of the mood with his amazing camera work.

It was also shot during the holiday season, so people were in a happy mood. Emmylou brought a handmade Christmas ornament you can see hanging in some of the shots. And my partner Rosanne Cash came into the studio with her newborn Carrie. I don’t think she was even two weeks old. Rose handed her to me and I held her tight while running sound for the track Rose and John Hiatt did together. Carrie never made a peep!

It was crucial to capture the acoustic nature of these sessions. What was your audio setup like?

I had a simple Nagra tape recorder just to have an edit track to work from and to record interviews. I had a single mic that I would place in the room to catch all the conversation, as some of that was obviously not recorded for the album and we wanted it for the film. Although, during our interview with Emmylou Harris, the band loved what she said so much that those comments ended up on the album.

Do you remember any particularly fun encounters with the legendary musicians in the film?

We caught some great moments and they’re in the film. The ending of a fast-paced “Valley Road” with Bruce Hornsby was a favorite. The band all stops for a second to look at each other — then they realize they got it and they all start shouting and cheering.

After Jimmy Martin’s session one day, he went out for some cocktails and came back into the studio while Ricky Skaggs was working. We captured Jimmy (feeling no pain and wearing a coonskin cap) as he and Ricky ripped into a spontaneous version of “The Old Crossroads.”

This film was Mr. Acuff’s last filmed appearance and that was special. I have to say — each time the song “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” was performed, it was magic. Every single time.

The Dirt Band did a masterful job of keeping things upbeat and fun for everyone. Every one of them was so engaged in each song — and brought individual songs or artists to the project. They were like marathon runners, giving their all each day and then coming back the next day to do it again.

What were some of the hurdles you faced in the film’s creation and release?

The very existence of this film was due to a California record company exec telling me that we would be in breach of contract if we didn’t deliver this video for the agreed-upon budget. When I explained this “song” was going to require us to shoot for several weeks, this delightful woman didn’t seem to care. I think it was meant to be — we HAD to make it work.

Bill couldn’t figure out how to light the dimly lit studio without a pile of light stands in every shot — and in everyone’s way. So, he created a giant light box and hung it from the ceiling. You don’t see a single light stand.

We didn’t have any money to sync up the video with electronic slates or fancy editing gear. I moved a cuts only 3/4″ video editing system into my office and had to sync the shots up by eye more than once… if we didn’t have an audio track running. Watching Mark O’Connor’s fingers or Earl Scruggs’ fingers to make sure you lock each note made for some very long nights. Those fingers were flying!

Rosanne and I sold 50 percent of the film rights to a company who released it on home video. Unbeknownst to us, the entire archive of that company was acquired by another company that isn’t interested in letting us buy the remaining rights, so we remain in limbo.

What do you hope a modern viewer will experience when watching these clips 30 years later?

This is a piece of living history. The first Circle album influenced every single musician I know. Watching the creation of the second — especially thirty years on — reminds you what kind of power music has.

It makes me sad to count off how many artists from this project are gone now: Johnny Cash, all of the Carter Sisters, Earl and Randy Scruggs, Vassar Clements, Chet Atkins, Levon Helm, John Denver, Roy Acuff, and dear Roy Huskey, Jr. In this world of instant technology, I think this 30-year-old film puts the viewer right into the studio for a front row seat at this amazing recording. I’m very proud of it.