When it came to guitars, gadgets and such, JJ Cale bought plenty of stuff and more often than not wound up giving it away eventually. When it came to his music, however, Cale was not one to cast anything aside. Over the decades of his long and storied career, he amassed hundreds of recordings of songs, fragments, alternative mixes and other sonic ephemera. Fifteen songs, all complete and finished by Cale himself, have been rescued from his hard-drive vaults for the posthumously-released new album Stay Around.

“I wanted to make sure everything on this was really ‘new,’ songs that people hadn’t already heard,” says his widow, Christine Lakeland Cale, who oversaw the project. “You know, you go on YouTube and there’s a bad-sounding grainy video from a gig somebody recorded on their phone. I tried to find things that hadn’t even been out that much. I was looking for the most Cale I could give people.”

Cale, who died from a heart attack in 2013, was a marvel of consistency as a recording artist. Well beyond “After Midnight,” “Cocaine,” and his other signpost compositions, he left behind more than a dozen albums long on relaxed, amiable grooves. So it should come as no surprise that Stay Around offers that same level of quality, even though it consists of recordings spanning more than three decades.

The album’s tracks range from solo recordings to full-band arrangements, with highlights including the loping ode to road life “Chasing You” to the title track’s romantic crooning. Christine compiled the material in collaboration with her late husband’s longtime manager Mike Kappus, who was well-versed in Cale’s working methods. It wasn’t unusual for Cale to leave songs sitting around for years, or even decades, before releasing them. “Roll On,” the title track of Cale’s final 2009 studio album, was a song he’d had in the bag since the mid-1970s.

“I was kind of in on the complete evolution of it all,” Kappus says. “He would send me cassettes, with something like a picture of his driver’s license as artwork, just this private little clever thing between us. We’d be talking about the next album and not everything he sent would make it. At one point I told him, ‘Man, you’ve got a couple of really good, solid records here.’ But the temptation for any artist is to do what’s fresh and that’s what would happen. So there was all this material left over.”

Christine admits it took her “a couple of years of walking around foggy and not all there” until she felt up to diving into Cale’s recorded archive, which was not stored on a pile of tapes. Instead, Cale left behind about 50 hard drives on Alesis HD24 machines, a format Christine says has been obsolete for years. But Cale didn’t upgrade beyond that because the format worked and he was comfortable with it.

“He used to joke to people, ‘I’m too old to learn something new, I like what I have and I use my ears, not my eyes,’” Christine says. “So he never made the transition to Pro Tools. He could hear peaks of distortion that had to come out, instead of seeing a line on a screen to edit. He liked the familiarity of his home studio because he didn’t have to spend any time setting things up — just flip the switch and get creative.”

But just because Cale’s recording methodology was to set it and forget it, one shouldn’t conclude that he was any sort of behind-the-times Luddite. Cale was a skilled studio technician who “loved engineering more than anything else,” according to Kappus, and he had a lifelong fascination with the tools of his trade. After buying new gear or instruments, Cale would usually take them apart and rebuild them. He’d do the same thing with records, after a fashion, going to record stores and buying the entire top 10 bestsellers to study.

“He’d want to check out whatever people were buying,” Kappus says. “Not to try and copy, but to check the engineering and production aspects. We were at McCabe’s Guitar Shop in Los Angeles once, where most of the people working were pretty into acoustic or folk music. And Cale starts talking about the mixes on ‘Back That Ass Up’ and some new Britney Spears record. Everybody there was going, ‘What?!’ They figured he’d only know about Willie and Waylon. But he had a lot of curiosity and he’d appreciate the mixing and recording of that stuff in a very true, knowledgeable way. It was the furthest thing from snobbery.”

Of particular note on Stay Around is its one song that Cale didn’t write, “My Baby Blues” — which Christine calls “my nod of self-indulgence,” because she wrote it herself. “My Baby Blues” is a song she and Cale recorded in 1977 at the first session where they met. Cale’s version here dates back to 1980 and Christine considers it a real find. But her favorite cut on the album is the title track, a meditation on the pleasures of being with the one you love (“Stay around, stay around, girl/And let’s make love one more time”).

“That one just floored me when I found it,” Christine says. “I couldn’t believe that one, and the guys at the label came up with the idea to make it the title because, ‘We hope his music stays around.’ That’s brilliant, how come I didn’t think of it? But I was too close to it. It takes a village.”

Some of the solo recordings are particularly intimate, especially “If We Try,” which comes by its kitchen-table feel honestly. That was one of his favorite places to record when he was home alone, and the track feels “as if you’re right there sitting at the table with him,” Christine says.

While Christine isn’t yet thinking about a follow-up, there’s more than enough material still in the vaults to make another album, which could be 100 percent previously unheard material the way this one is. And she thinks that the spirit of her late husband, who would have turned 80 last December, probably approves.

“I have had a lot of weird things happen,” she says. “Probably more so during the foggy period. But even now, things happen where I think, ‘Somebody’s just making sure things go this or that way.’ This world can’t just be it. I do think there’s something once we leave here, I just don’t know what. There’s got to be another level of intelligence in the universe because we’re such a flawed species. Without sounding too much like an old hippie, it seems like there’s the ability to let somebody know it’s okay. And he has.”

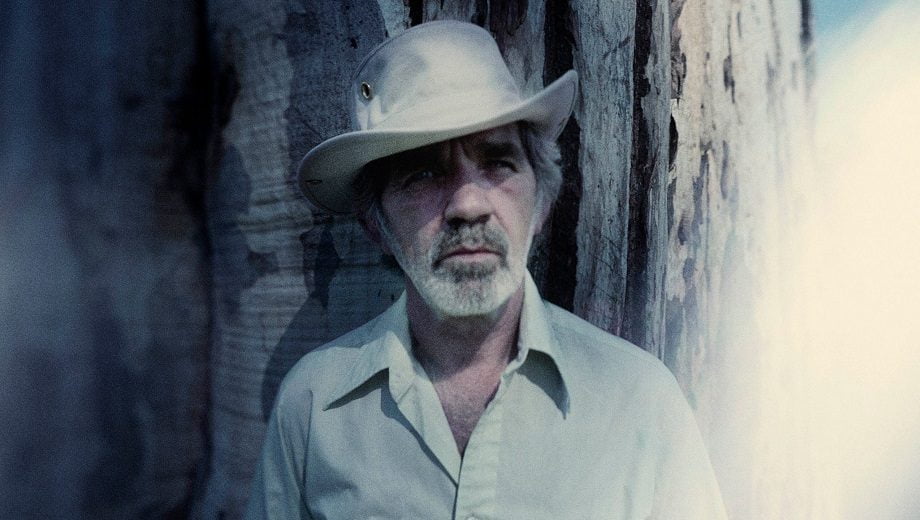

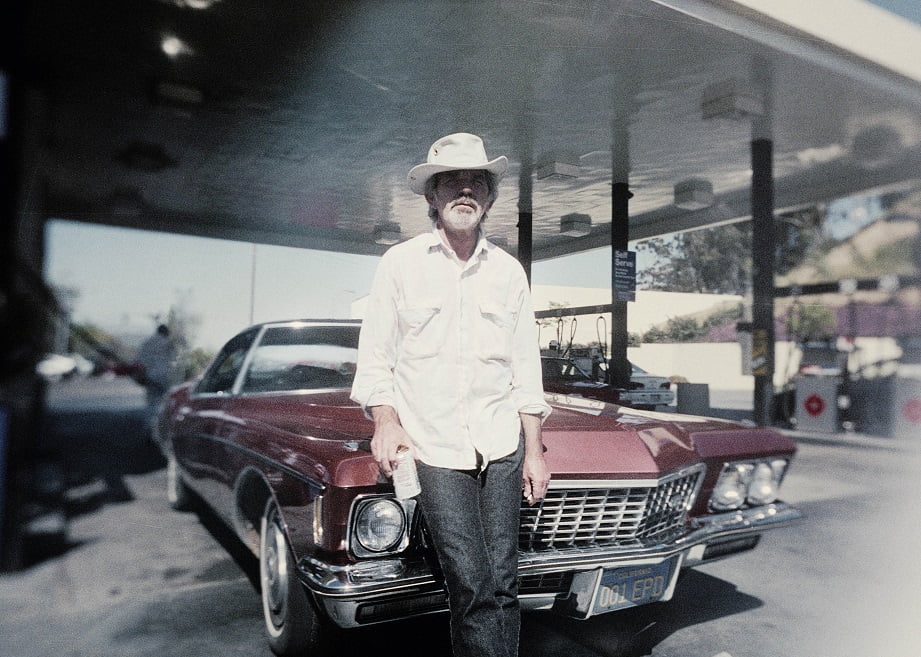

Photo credit: Stephane Sednaoui