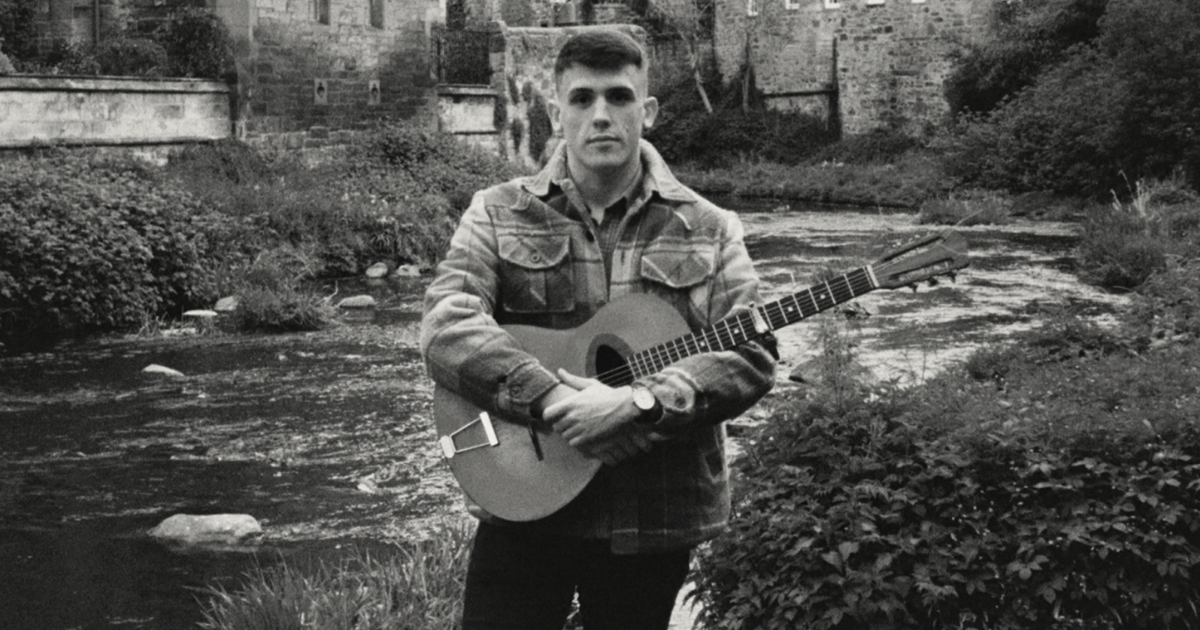

Sam Shackleton is a good example of the successful contemporary songwriter – a Scottish traditional folk singer with some formal education in musicology. He posts excellent, moody clips online; he goes viral enough to open for bands and artists like the Mary Wallopers or Willi Carlisle; and he releases music on Bandcamp. Though he could easily slide into a minor but culturally significant record label, he released his new album Scottish Cowboy Ballads and Early American Folk Songs independently; when a writer emails him, the answers come back on a plain Hotmail account, his avatar a famous 19th century painting of Robbie Burns.

There is something telling in this amalgamation: the 200 years of cowboy songs, the move between America and Scotland, the slightly old-fashioned email address. Even Shackelton’s very contemporary distribution methods envelop other kinds of tradition, the busker as troubadour or a work song floating across oceans. For example, when he sings “The Butcher Boy,” his framing includes that Mary Wallopers’ cover from a couple of years ago, the Sinead O’Connor version before that, and the Tommy Makem version before that. And he also echoes those who sang before them. “The Butcher Boy” is not even a cowboy song, though. When he offers songs like “Chisholm Trail” or “I Ride an Auld Paint,” something shifts in how he sings them.

The cowboy song is muddled – it is the expression of poor, often Black, Hispanic, or Indigenous agricultural workers, telling explicit stories about their lives – but like a shanty, it is also a song that aids labor, in passing the time and moving the livestock along. These dual instincts of work and entertainment gathered into an oral tradition, which was translated into grand public spectacles. These spectacles were later depicted on radio, film, and television, abstracted and cleaned up. When a singer chooses to return to these songs, their versions are always paratextual – they are making choices of interpretation. When Shackleton sings the verses in “Chisholm Trail” about punching bosses or selling cowboy gear, he is foregrounding a kind of economic subtext, which might be less fun and seems more serious.

It reminds me a bit of growing up in Alberta (maybe because on “Roving Cowboy” Shackleton sings about crossing the Rockies and the “cold and distant plains”), or my relations in Calgary, that city mostly named after Scottish figures, romantic still for a set of cultures that doesn’t exist. How much easier it is to consider the romance of the West without considering the isolation of it all. Men would be sent from places like Scotland to the prairies as part of a great colonial project; the rascal sons of minor aristocracy, rampaging across the land. That roving grew into myths of grand cowboy narratives. The big rodeo turned into a banal bacchanal. When Shackleton sings in “Roving Cowboy” about leaving “his good old father” or “his friends and home there,” he refuses the grandeur and returns to the profound isolation. A kind of homecoming in place and in time that may never occur.

Talking to Shackleton via email for Good Country, I learned that an album I first thought was a small jape was really a sophisticated conversation with these traditions, lands, and desires.

I am curious about why cowboy ballads and also how you define a cowboy ballad – some of the songs seem very clearly part of that tradition, but some to be an extension of it. Is “Butcher Boy” a cowboy ballad?

Sam Shackelton: I’ve always been a fan of cowboy music since spending many hours watching old Westerns, when I’d go through and spend the weekends with my dad as a kid in a wee Scottish town called Bridge of Alan. For me, the best part about them was the music, singing, whistling, and yodeling. Even to this day I think it’s pretty hard to find anything cooler than Dean Martin singing “My Rifle, My Pony and Me” in Rio Bravo.

Much of my early musical influences were inspired by my father. I remember vividly the first time he showed me the excellent Woodstock: 3 Days of Peace & Music documentary of the 1969 festival, which first led me down the path of learning to play and wanting to be a musician – though at the time I didn’t think I’d ever be good enough to step on a stage. In regard to the album title, I originally was going to just call the album Scottish Cowboy Ballads, but decided to throw in the “Early American Folk Songs” to allow me to add a broader range of songs to the album such as “The Butcher Boy” or “O Death.”

Could you talk a little bit about the loops of influence which exist in folk music circles. The Scottish ballads which end up in Appalachia, from the 18th century onward, but also the dual folk revivals in the 1950s and 1960s? Where do you see your place in the ebb and flow of these revivals or these conversations?

Mainly through my own research and watching many hours of old music videos and documentaries on YouTube as a teenager, I discovered the American and Scottish folk revivals of the 1950s and ‘60s and knew I’d finally found my musical home, so to speak. I strongly believe that what you put in is what you get out, as a musician, when it comes to inspiration, so I deeply immersed myself in this music for many years. Still to this day only really listen to music from this period or those who can capture a similar sound today. I was deeply inspired by Woody Guthrie and also by his close friend, Cisco Houston, especially his album, Cowboy Ballads, which was a big influence on my latest album and much of my earlier music too.

I’ve always been drawn to less commercially popular musicians, such as Walt Robertson or Alex Campbell, those with incredible talent but whose work went generally under the radar in favor of bigger, more commercialised folk artists. People often talk of Guthrie when referring to the folk revival, but even his songs were greatly aided by Cisco’s harmonies and Sonny Terry’s whooping harmonica, another huge inspiration of mine.

I also had the great privilege of studying at the School of Scottish Studies at the University of Edinburgh for 5 years, where I got both my undergraduate and master’s degrees. The School of Scottish Studies was founded during the Scottish folk revival in the 1950s and was based on a vast collection of field recordings collected primarily by Calum MacLean – brother of the legendary Gaelic poet Sorley MacLean – and renowned ethnomusicologist and poet Hamish Henderson. [Henderson] made many of his early Scottish recordings with Alan Lomax during his time in Scotland in the ‘50s.

I focused primarily on Scottish/Celtic studies, Scots-American emigration and musical traditions, and ethnomusicology, with a specific focus on the work of Alan Lomax – and what I identified as the new “digital folk revival,” which is happening right now on social media. In my masters thesis, I argued that modern online digital communications technologies (such as social media platforms like YouTube) are facilitating multiple new folk revivals. Lomax prophetically identified this in his 1972 paper “Appeal for Cultural Equity,” where he identified both the risk of mass communication technologies to traditional folk cultures, but also their extraordinary ability to preserve and facilitate folk revivals by allowing everyone to share and participate in folk traditions on a vastly more even playing field. All you need now is a mobile phone and you can participate in the digital folk revival, sharing and listening to songs from every corner of the world.

In relation to your original question, it is indeed true that many of the songs that were sung during the folk revival in North America at that time (and throughout American history) also had a very close and deep connection to the mass emigration of people from Scotland, Ireland, England, and Wales during the 18th and 19th centuries and beyond. This is evident in songs such as “Pretty Saro,” which is also on the album. This was a song sung commonly in England but was lost to time, only to be rediscovered being sung in the mountains of Appalachia by early song collectors. And, as such, the song became popular again across the Atlantic. This is a perfect example of how these early folk revivals facilitated this full circle of cross-cultural transfer.

How was this album affected by the large-scale American touring you have done in the last few years?

My time spent touring in the USA and Canada was certainly a big influence on this album. I traveled all over the states, starting in Nashville, where I then traveled through Kentucky and Tennessee with my good friend and director of the YouTube channel GemsOnVHS, Anthony Simpkins – his channel being another great example of the digital folk revival in action. We recorded a bunch of amazing music in the hollers and I met many amazing musicians during my time there, such as Benjamin Tod and Ashley Mae from Lost Dog Street Band.

[They] kindly invited us to spend the night at their house in rural Kentucky along with Jason O’Dea to shoot some guns (my first time doing so in the USA) and play some songs around the campfire. I remember playing Benjamin Tod an old Scottish ballad called “Tramps and Hawkers” on the banjo by the fire, to which he then responded that he was also aware of versions of the same song that had been sung in the American folk tradition. Again, highlighting this close cross-cultural connection between the Scottish and American musical folk traditions. I then toured all across the East and West Coasts of the USA and Canada with my good pals, legendary Irish folk band the Mary Wallopers, before selling out a couple shows of my own on the East Coast.

I noticed that the album’s songs are mostly very short – some under two minutes. Can you talk a little bit about that? Is that related to busking? How else does busking appear in these kinds of recordings? How does busking online relate to busking in person?

Since this is the first ever album I will be releasing on 12” vinyl LPs, I decided to try and fit as many songs on it as possible. Obviously, due to the physical limitations of the vinyl medium, I had to make sure my album was within a certain length of time, hence why some of the songs may seem shorter. Although there are a good few short songs on there, you will indeed find a few longer ones such as “Old Rosin the Bow” or “The Blackest Crow.”

I know that the Mary Wallopers sing “Butcher Boy,” and it is often a touchstone for Irish singers (the Mary Wallopers, Lankum, Lisa O’Neil, Sinead O’Connor, the Clancy Brothers), but also the Irish diaspora. In fact, in a live recording from the Clancys, Tommy Makem calls it, “Well known in America.” What is your relationship to both the song and the people listening to it? How do you make songs thought commonly to be American or Irish to be Scottish?

“The Butcher Boy” is a class wee ballad and you are right in noting that it is indeed popular amongst Irish artists such as The Clancy Brothers, their version being my favorite. However, the history of this ballad and its origins are far more complex, as this ballad is actually derived from multiple old English broadside ballads such as “Sheffield Park,” “The Brisk Young Sailor,” and “The Squire’s Daughter,” to name but a few. Many versions of this song have been collected across England, Ireland, Scotland, and North America. It is perhaps one of the best examples of a cross-cultural folk ballad I can think of.

I had actually stopped singing this song for a long time after what happened with my dad, as the later verses were far too similar to what I had experienced with my father’s suicide. But, despite how hard it was for me to sing again, I felt it absolutely needed to be included on this album. If anything comes from people hearing that song in particular, I hope that they show some love to the people in their lives who may be struggling. It’s not easy being a human on this cruel old rock hurtling through space, so we all need all the love and support we can get.

I noticed that you dedicated this album to your father – what was your relationship to him?

Yes, I dedicated this album to my father, as it’s my first major release since he tragically took his own life in the summer of 2023. We also used to sing many of these songs from the album together when I was younger. As I mentioned at the start, my father has always been a huge influence on my music and I can say for certain that I wouldn’t be a musician today if it weren’t for him. From buying me my first guitar to constantly taking me on stage to perform with him as a child.

My mother and father actually used to be in a band together before I was born called Big Shacks. My mother, Kim, was the singer and my father, Norman, was the lead guitarist. I have many fond memories of busking with my dad on the streets of Edinburgh and Glasgow as a child, too. It was something that brought us very close together over the years. When he died, it really took a huge toll on me. I was actually down in England opening for Willi Carlisle when it happened and I was also in the process of getting my American O-1 visa at the time. I decided to still go ahead with the first American tour a few months later, regardless. However, afterwards I was in a really bad place mentally, so I decided to take a long break from performing until I finally felt ready to return. In that time, I recorded this album and as such I have dedicated it to his memory. I’ve now also returned to touring in the last few months and will be announcing a really big tour of my own in the very near future!

What makes a Scottish Cowboy different than other cowboys?

Scotland has a very long history of cattle droving, going back many hundreds if not thousands of years. There is indeed much to be said on the topic of Scottish cowboys and their influence on the conceptualization of the American cowboy and the Wild West. A good place to start, if you want to research this fascinating topic further, is the fantastic book by Rob Gibson called Highland Cowboys: From the Hills of Scotland to the American Wild West. In it, he details the links between the two cultures, as not only did the thousands of emigrants from the Scottish Highlands and Lowlands bring with them their musical culture and songs to the New World, they also brought with them their unique way of life and cattle-herding culture and practices. Not to mention the practice of cattle rustling, which although not unique to Scotland was a very common yet serious crime throughout Scottish history.

To further emphasise this connection, I included the song “Chisholm Trail,” as this song is sung about the historic cattle trail that runs from Texas to Kansas, which is named after the famous half-Scottish, half-Cherokee cowboy, Jesse Chisholm.

Photo courtesy of the artist.