Long before folks were strumming guitars and picking banjos, they were telling stories. Stories about origin, hopes, dreams, and fears, and lessons learned. These stories guided lives and relationships, became myths, legends, and songs, and were passed down for generations and adjusted for place and time. From “The Knoxville Girl” to “Down in the Willow Garden,” to Lindi Ortega’s “Murder of Crows” and Tyler Childers’ “Banded Clovis,” the spooky story looms large in bluegrass, old-time, and Americana music.

For the season, we asked BGS readers to share their own roots music-themed writing with us in the form of spooky fiction, creative non-fiction, poetry, or cross-genre writing. We were not disappointed! Below, Emily Garcia’s young musician narrator achieves justice for poor Rose Connelly of “Down in the Willow Garden,” and Stuart Thompson details the sad fate of two brother fiddlers who became entangled with the wrong woman.

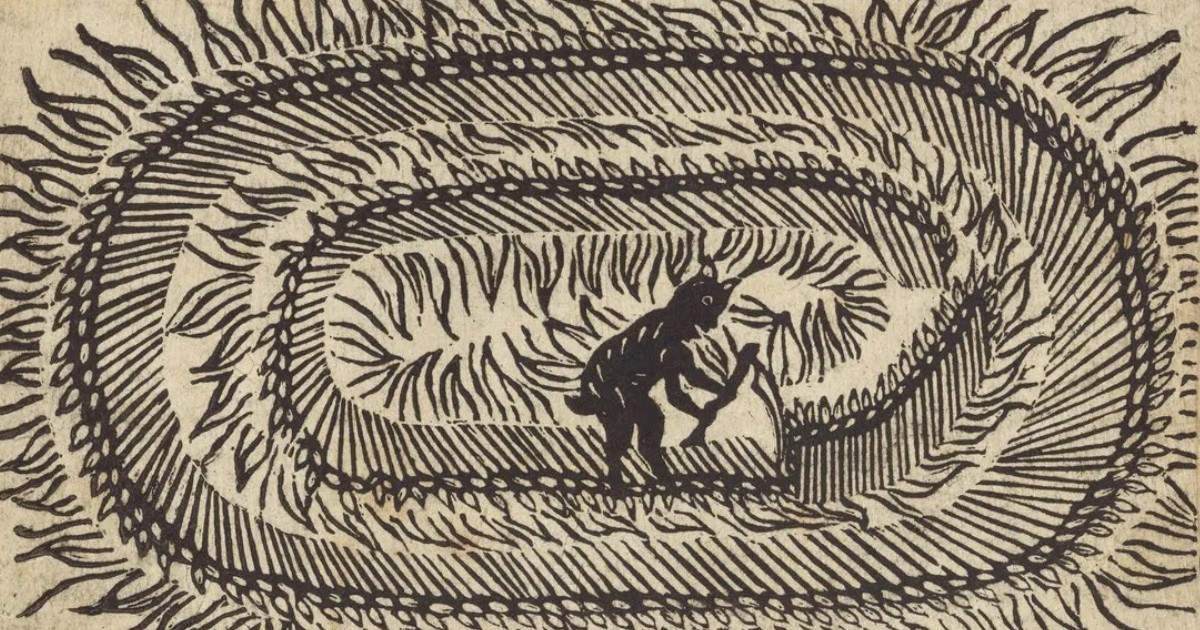

But first, we share with you an old tale of the farmer and the devil, regarding the origin of crop circles, found in a newspaper from 1678 – from which we’ve also pulled the creepy and fantastic woodcut we’ve chosen for lead image.

With this series, we hope to honor and continue the long tradition of storytelling and verse that has lived alongside and contributed to our favorite genres of music.

“The Mowing Devil Or, Strange News Out of Hartford-Shire”

Being a true relation of a farmer,

who bargaining with a poor farmer about the cutting down three half acres of Oats;

upon the mower’s asking too much, the farmer swore, that the devil mow it, rather than He;

And so it fell out, that that very night, the crop of oats shew’d as if it had been all of a Flame:

But next morning appear’d so neatly mow’d by the Devil, or some infernal spirit, that no mortal man was able to do the like.

Also, how the said oats now lay in the field, and the owner has not power to fetch them away.

Source: The Public Domain Review. August 22, 1678.

“Beneath the Sun, Above the Moon”

by Emily Garcia

The Hunter’s Moon, red from eclipse, slides above the pines and half-bare maple trees, its hollow stare cast over Virginia’s Appalachian Plateau. Behind it, the night is black as pitch.

“You okay, Wills?” asks Annie. No, she hasn’t been okay in months, but Annie doesn’t want to hear that.

“Yeah, of course!” Willow rosins her bow, trying to ignore the wailing in her ears.

Annie glances down, rocking the toe of her boot into a groove on the worn cabin floor. “I hope I wasn’t too pushy…I just thought playing again might help.”

Two weeks earlier, over the phone, Annie had been less concerned about being pushy. “Willow Rose O’Connell, I’m not taking no for an answer. You are coming to Hunter Jam Weekend, just like you have every year for the last four years. I will not let my best friend rot away in some North Carolina suburb just because one tour didn’t work out.”

Didn’t work out. That was the story she let everyone believe: she had quit the gig of a lifetime halfway through the European arena tour, all because she couldn’t handle the pressure and had a nervous breakdown in a hotel room in London. It was a breakdown so bad that she flew straight back to Nashville that night, packed her entire apartment, drove eight hours to her parents’ house in Raleigh, and was now living in her childhood bedroom strung out on Xanax.

“What a shame,” people liked to say.

Now, she forces a smile. “I appreciate it, Annie. I’m good. I’m glad I’m here.”

Relief washes over Annie’s face. “Okay awesome. Let’s go, then. You don’t need to solo or anything, just play.” Annie grabs her mandolin and heads for the door. Willow follows, fiddle tucked neatly under her arm.

They wind through a wooded path lit only by the moon, towards the fire where the rest of their group has already started jamming. She can’t shake the wailing sound. An old recurring nightmare from childhood, a screaming woman next to a riverbank, has resurfaced with a vengeance since she left the tour six months ago. On the worst nights, the screams would weave themselves around memories of her grandmother’s shriveled voice singing old folk songs by the fireplace.

My race is run beneath the sun, the devil is waiting for me.

What no one knows is that an hour before the nervous breakdown, she forced her way out of the back of the tour bus, shaking uncontrollably, the manager’s whiskey breath staining the air. She had escaped the worst, thank god, but his slurred voice taunted behind her. “Don’t even try telling anyone, Will. You know I can ruin you.”

She knows. She knows how this industry works.

They reach the circle and Willow perches on a stump by the fire. There are a few awkward mumbled greetings, her former companions from the Nashville scene now looking at her like the ghost of an old friend. “Okay, where we at?” Annie cuts in. “‘Deep River’?” And with that, the jam resumes. Every time solos reach her, she leans to Annie and passes them off. The screaming is back, louder than usual, mixing with the songs into a sideways cacophony that makes her feel sick to her stomach. Her playing drifts off, she squeezes her eyes shut. The fire feels like it’s taking over her body.

The tune ends, and she gets up. “Sorry guys, I think I need to go lie down for a second. My head is killing me.” A murmur of concern ripples through the group but she can hardly hear it. She heads up the path towards the cabin.

The screaming is getting louder, and the ground feels like it’s shifting beneath her. Vertigo, maybe. The devil is waiting for me. She stumbles forward, barely conscious of where she’s going. You know I can ruin you. She reaches for a tree to steady herself, but the trees seem to be sliding up and down the periphery. She falls, hands driving into the dirt. Eyes squeeze shut.

The screaming stops.

A faint sound of banjo and a slurring male voice touches the air. She slowly pushes herself up, eyes adjusting. The sun is out, hanging red and low over the horizon, as if the moon has reversed its course. A river runs to her right.

In front of her lies a young woman, wispy brown hair fanned across the dry grass, and a half-empty bottle of burgundy wine next to her. She could almost be peacefully asleep, if not for the 15-inch knife sticking out of her chest and the crimson blood soaking her white cotton dress.

She stares at the woman like a mirror, the smell of whiskey burning her nose, when she hears him, gasping. She looks up. He’s in a loose-fitting linen shirt and dirty denim overalls, his eyes bloodshot, a banjo clutched in his left hand. His splotched face drains to white as their gazes meet.

“Rose– I– Rosie, my dear– I– I– I… my God, my God.” His trembling voice is centuries old. He glances wildly at the dead girl’s face, then back at Willow.

Her fingers curl around the knife handle and she pulls upward.

“I didn’t m-m-mean… I– I– I… Rosie please, I love you.”

She raises her bow arm. Her movements are not her own. Virginia turns red beneath the sun. The screaming begins again, different now, deafening.

Then it stops.

Heavenly quiet. And then a heavy splash.

It’s dark again. The moon is fixed to the night sky, and she’s standing at the edge of the circle. “You scared me!” Annie raises her eyebrows. “You okay, girl?”

“Yeah I’m good. Just needed a quick nap.”

Willow picks up her fiddle, which she had left leaning against the stump, and gives it a quick tune. “Okay y’all. ‘Wheel Hoss’? I’ll kick.” Without waiting for a reply, she jumps in. A few hollers from the group, and they all launch after her. Her fingers dance across the strings as everyone else holds back to hear her, finally, play again.

The final notes ring out. Silence, then the circle explodes into wild cheers and laughter.

Annie turns to her, grinning. “See Will, I told you playing again would help…” Her voice trails off.

Willow follows Annie’s stare. Her hands, strings, and fingerboard shine in the firelight, covered in blood.

Emily Garcia is a writer and fiddle player who spent her early career studying and performing within Nashville’s roots scene. She is now based in southern Maine and continues to perform, travel, and write stories inspired by American music and place. You can follow her work on Instagram at @imemilygarcia.

“Brother Fiddlers”

by Stuart Thompson

Up in Clear Creek County, when the wind is lying still,

They say you can hear it high above the Argo Mill.

The sound is lonesome, and the sound is low,

Like the fiddlers pointing out the guilty with their bows.

Will and Tom were brothers, bold and bound for gold,

They followed the rush where the rivers ran cold.

They staked their claim where the tall pines lean,

And they carved their camp in a cut of green.

By day they dug with blood and sweat,

By night they played in the dry sunset.

Twin fiddles rose in the old saloon,

And the one they played for was a gal named Lou.

She poured the drinks and danced the floor,

With eyes that knew what men were for.

She’d kiss you soft, then slip away–

Leave you lost ’til your dying day.

Up in Clear Creek County, when the wind is lying still,

They say you can hear it high above the Argo Mill.

The sound is lonesome, and the sound is low,

Like the fiddlers pointing out the guilty with their bow.

They struck it rich – oh, mother lode!

A vein so thick it near broke the road.

One would sleep while the other stood,

Guardin’ gold in the dark pine wood.

But Lou, she schemed with a serpent’s smile,

Fed them lies and love the while.

“I want the stronger,” she said with a kiss.

“One who’d fight for a prize like this.”

So Will took watch on a moonless night,

With rage in his heart and death in sight.

Tom came quiet, just to check the claim–

But Will saw red and took his aim.

The shot rang once, and his brother fell,

And all went silent but the echo’s knell.

Will knelt down with a choking cry–

Then Lou stepped out with a pistol high.

No words she spoke, no tear she shed,

Just one quick flash – and Will was dead.

She buried them both where the cold creek bends,

And set her sights on richer ends.

Up in Clear Creek County, when the wind is lying still,

They say you can hear it high above the Argo Mill.

The sound is lonesome, and the sound is low,

Like the fiddlers pointing out the guilty with their bows.

She bought new gowns and she drank top shelf,

But Lou could never escape herself.

At night she’d wake with a strangled cry–

Hearing bows that scraped like a widow’s sigh.

She climbed the trail where the cold winds moan,

To the shaft where the brothers’ blood was sown.

And some say madness took her mind–

She walked into that hole and left no sign.

Now nothing grows where the gold once lay,

Just wind and whispers and strings that play.

The miners say, when the stars hang low,

You’ll hear twin fiddles weep and glow…

Up in Clear Creek County, when the wind is lying still,

They say you can hear it high above the Argo Mill.

The sound is lonesome, and the sound is low,

Like the fiddlers pointing out the guilty with their bows.

Stuart Thompson is a husband, dad, and mandolin picker from Denver, Colorado. He can be found online at @stu.art.thompson.

Stay tuned for more opportunities to publish your own writing or art on BGS in a future collection!

Collection edited by Rachel Baiman and BGS staff.

Lead Image: Woodcut, “The Mowing Devil Or, Strange News Out of Hartford-Shire”, August 22, 1678. Source: The Public Domain Review.