For the past eight or so years I’ve been making this joke that we (the music industry) should “Give women Americana.” As in, if we gave the entire genre — and bluegrass and country and old-time and folk, for that matter — to women and femmes and non-men, I wouldn’t so much miss the men and the music would certainly be well cared for and well set up for the future.

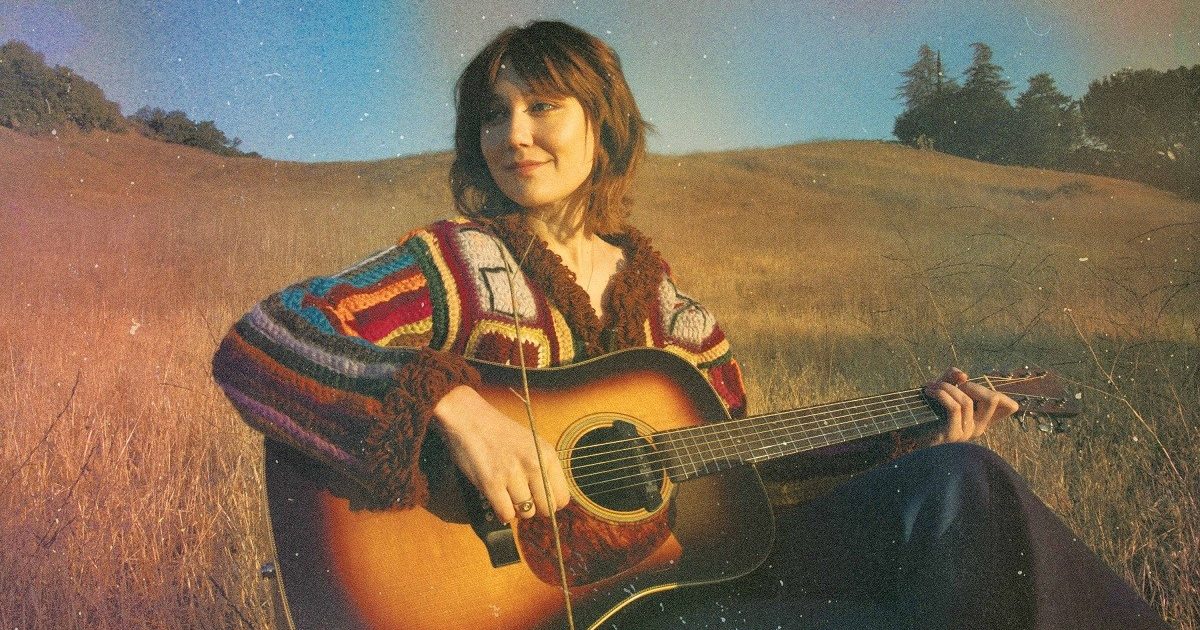

My point, as I continue to make this joke year after year to many puzzled reactions, is that women and femme roots musicians have and will always be my favorite artists, creators, songwriters, and pickers. As I crafted my debut solo album, 1992 – often with incredibly talented women like producers and engineers (and pickers) Cathy Fink & Marcy Marxer, mastering engineer Anna Frick, photographer Laura E. Partain – the music that inspired, informed, and challenged me most through this release was all made by women. (Ask me sometime about my monthly Spotify playlist, Don’t Need No Man.)

When BGS approached me to make a Mixtape to celebrate 1992, I knew I had to share some of the women who helped me realize, musically, artistically, socially, emotionally, that there could be a home for me in bluegrass, largely because they had created such a home exactly for me. Here are a few of my bluegrass, old-time, and country inspirations, all of whom have filtered into this album in one way or another. – Justin Hiltner

Ola Belle Reed – “High On the Mountain”

1992 was tracked in Ashe County, North Carolina, in a little town called Lansing nestled into the Blue Ridge Mountains, right where Tennessee, Virginia, and North Carolina meet. I love it out there on the mountain, in the wind, in the clouds, on the rocky little road cuts and switchbacks through the hills. Lansing also happens to be the hometown of a legendary Appalachian musician and bluegrass forebear, Ola Belle Reed. A banjo she once owned and had signed hung on the wall beside me while I tracked every song. I definitely see my album as stemming from the lineage of Ola Belle, humbly and gratefully.

Cathy Fink & Marcy Marxer – “Hold Each Other Up”

I’ve been so lucky to collaborate with folk icons, Grammy winners, and children’s music legends Cathy & Marcy in so many different contexts and scenarios, every single one delightful and fulfilling. They’re amazing mentors and encouragers and while we recorded 1992 we had to take the chance to channel their amazing attitudes and worldviews into a COVID-inspired (or -instigated) track, “Hold Each Other Up.” I love getting to pick and sing with these two, and their engineering, production, wisdom, and guidance all made this record possible.

Laurie Lewis – “I’m Gonna Be the Wind”

Long before I ever got the chance to tour and perform with Laurie Lewis she was a hero of mine, someone I looked up to and knew would be a bluegrass legend and stalwart who could or would accept me for who I am. Turns out, often in bluegrass, it is okay to meet your heroes, because when we met and I got to work for her, it turned out I was absolutely right. Her writing style, her artistic ethos, and the way she infuses pure bluegrass energy and her personality into everything she does reminds me I can be who I am, play the music I play, and write the way I write. This song picks me up whenever I’m down and gives me self-confidence and optimism when I need it most.

Alice Gerrard & Hazel Dickens – “Mama’s Gonna Stay”

I never had the honor of meeting Hazel before she passed in 2011, but Alice Gerrard and I have become friends over the past six years and honestly, if 17-year-old Justin knew he’d become friends with this Bluegrass Hall of Famer, he’d die. We happen to share a birthday, too. Alice is a gem, a trailblazer, an unassuming and unrelenting activist and organizer and community builder. She inspires me in all of the above, but especially in her willingness, across her entire career, to write music about things no one else was writing about. This song, which Laurie Lewis turned me onto (she performs it as well), is a perfect example.

View this post on Instagram

Elizabeth Cotten – “Wilson Rag”

Playing shows and recording totally solo is often terrifying. Especially as a bluegrass banjo player used to playing in five-piece lineups. It took many years and lots and lots of practice time and experimental shows to figure out how exactly I wanted to arrange songs, build shows, create and ride a storytelling arc during my shows, guide an audience, and do all of that confidently with just a voice and banjo. Artists and pickers like Elizabeth Cotten gave me frames of reference for what I was doing that felt solidly bluegrass, but still building a show and sound that feels fully realized and not lacking for being minimal.

Missy Raines – “Where You Found Me”

Missy Raines is another hero of mine that I feel so lucky to now call a friend. Despite coming from different generations and very different circumstances we have so much in common. It just sometimes astounds me that we can have seemingly endless conversations around if bluegrass (or country or roots music) are accepting and open; meanwhile one of the winningest pickers in the history of bluegrass and the IBMA – that is, Missy Raines – has always been both accepting and open. Who needs the sexist, homophobic, womanizing, problematic elements of bluegrass when you have absolute badass legends like Missy!? I once covered this song for a “Cover Your Friends” show and it continues to devastate me to this day.

Caroline Spence – “Scale These Walls”

When I first moved to town, Caroline Spence was one of maybe four or five people I knew in all of Nashville. We spent a lot of time together in those early years, back in 2011 and 2012, and pretty soon after that we wrote a song together, “Pieces.” We both loved it a lot, performed it here and there with different lineups and bands, but it never landed on a record ‘til now. “Scale These Walls,” from Caroline’s most recent album, is constantly stuck in my head. I love how it showcases her jaw-dropping skill for writing dead-on hooks that feel so organic and never corny. I love this song.

Molly Tuttle – “Crooked Tree”

Molly Tuttle and I wrote “Benson Street,” a track off my new album, together about five or six years ago. It’s a cute little number about longing told through the lens of an idyllic Southern summer. I love every chance I get to make music or write music with Molly. She’s a constant source of inspiration for me and proof positive that you can be a proverbial crooked tree in bluegrass and still carve a pathway to success. Plus, she’s another great example of a picker who can command an entire audience totally solo. Trying to steal tricks from Molly Tuttle? Couldn’t be me.

Rhiannon Giddens – “Following the North Star”

Rhiannon Giddens is the blueprint. When I think about my artistic future and the way I want to be able to glide between media, between contexts, between areas of expertise and subject matter, between pop and roots and so many other musical communities, I think of Rhiannon. The way she has built her career around her artistic and political perspective, so that no matter what she does it feels grounded in her personality and selfhood is exactly how I want to be as an artist and creator. Plus, I always want to be as big of a music nerd and as big of an old-time nerd as her.

Maya de Vitry – “How Bad I Wanna Live”

Maya is one of those writers and musicians who just makes me feel seen and heard and understood, and I know I’m only one in a huge host of people who would say the same. The vulnerability and transparency in her writing and the emotional and spiritual availability within it are astounding. Plus, she’s almost always, constantly challenging herself to consider the ways she creates and makes music outside of consumerism and art as a commodity. I moved to Nashville to be challenged, musically and artistically, by those around me and I feel so lucky to have Maya around me and a member of my community.

Courtney Hartman – “Moontalk”

Courtney Hartman’s “Moontalk” makes me feel like every single song I’ve ever written about the moon is good and right and allowable. (We both have quite a few songs about the moon, actually.) “Moontalk” feels like Mary Oliver incarnate in bluegrass-informed picking and singing. It feels meditative and contemplative, but not timid or insular – something I’m always trying to accomplish in solo contexts. I’m constantly inspired by Courtney and the way she centers community building in her music and life. She’s another one who, though she thrives performing and making music solo, you know that music came from a multitude of folks pouring through her.

Dale Ann Bradley – “He’s the Last Thing On My Mind”

I thank a few artists who have inspired and influenced me in a huge way in 1992’s liner notes and Dale Ann Bradley is one of them. I feel like I am constantly ripping off and (poorly) mimicking her vocal runs, phrasing, licks, and delivery. I think she might have the best bluegrass voice of all time, or at least it’s very very high up on the list. When I first moved to town I worked as an intern at Compass Records and just getting to be a small part of the team that worked a handful of her records meant so much to me.

Lee Ann Womack – “Last Call”

Lee Ann Womack is another who I thank in the album’s liner notes, another who I emulate vocally as much as I can get away with. I used to wear out this track and this album, Call Me Crazy, listening on repeat over and over. When I found out this song was co-written by an openly gay songwriter, it rocked my world. I already heard so much queerness in LAW’s catalog, and this confirmation came at a time when I needed to feel like I was given permission to exist in bluegrass, country, and Nashville. I know now that no one needs that permission, but it was critical then.

Linda Ronstadt – “Adios”

During the 1992 recording session I recorded a solo banjo rendition of this song, one I’ve been performing for years at shows. It means so much to me and Linda’s performance is stunning in its power and tenderness, a combination I’m often striving for. I hope to release it some time soon as a single, then again on a deluxe vinyl edition of 1992. It will not be the last time I pay tribute to Linda and her incredible career and catalog – plus, she is a huge bluegrass fan! It just makes sense to me.

Dolly Parton, Emmylou Harris, Linda Ronstadt – “Wildflowers”

When I had the pleasure of being a guest on the hit podcast Dolly Parton’s America, I sang this song and “Silver Dagger” among a few other from Dolly’s catalog that I felt had queer under/overtones. The response to my on-air picking was enormous, and there were immediate demands to release my versions of the songs. Cathy, Marcy and I recorded “Wildflowers” together during the 1992 sessions and it’s one of my favorite tracks that resulted from that week on the mountain. It’s gotten quite a lot of play, which I’m so grateful for, and always gives me an opportunity to talk about Trio and Dolly and how the story in “Wildflowers” parallels many a queer journey. It’s the perfect track to round out this Mixtape and I thank you for reading and listening along.

Photo credit: Laura E. Partain