Editor’s note: Read part one of Industrial Strength Bluegrass and the Dayton Bluegrass Reunion here

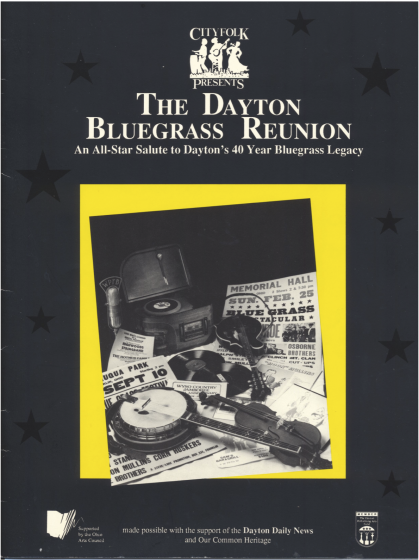

In 1987 I became involved with CityFolk’s Dayton Bluegrass Reunion, “An All-Star Salute to Dayton’s 40 Year Bluegrass History.” Between October 1987 and March 1989, I worked by mail and telephone to help shape the Reunion, planned for April 1989.

While this was to be called a “concert,” executive producer Phyllis Brzozowska envisioned it from the start as musical theater. I liked her idea — I’d long thought of bluegrass that way. My experience on the stage started at age 12, in a little theater company production of Our Town, Thornton Wilder’s 1938 Pulitzer Prize-winning play about a small community in the early 20th century. Wikipedia describes the play this way:

“Wilder uses metatheatrical devices, setting the play in the actual theatre where it is being performed. The main character is the stage manager of the theatre who directly addresses the audience.”

In Dayton, playwright Don Baker would have a role like that of the stage manager in Our Town, acting the part of a loquacious emcee, telling the story of the Dayton bluegrass community. He would work from a script that Larry Nager was writing. As he spoke, a screen behind him would show slides relating to the narrative’s cultural and historical points.

The concert was divided into seven acts, “Segment/Settings” of 12 to 15 minutes. Each featured a different group of musicians and had room for three to five songs and an encore. Don’s narrations opened each act. Planning reflected concerns about the content and sequence of the acts. How was forty years of artistic ferment to be represented?

When I spoke of the project to my bluegrass buddies, the first question was always “Will the Osborne Brothers reunite with Red Allen?” This 1957 show gives a good portrait of the band’s sound and repertoire — cutting-edge bluegrass of its era:

As the bluegrass festival movement ramped up in the ’70s, Allen and the Osbornes occasionally crossed paths. The Osbornes were doing well on the country charts with songs like “Rocky Top” that featured Bobby’s solo and trio high lead:

Allen, considered one of the classic bluegrass lead singers, had gone on to work in several good bands. He still approached audiences as he had in Dayton bars. Larry Nager explains: “Red loved the spotlight, making the crowds laugh (often at jokes more fitting for a stag party than a bluegrass club)” (Industrial Strength Bluegrass p.89). An on-stage festival reunion with the Osbornes had been tried, didn’t work out, and was now out of the question.

Who else would be in the concert? At the start planners thought in terms of contrasts in categories like venues (working-class bars; upscale nightspots, colleges), audiences (industrial working-class Appalachian migrants, yuppies, college kids), and radio (country, folk).

As we’ll see later, these categories overlapped; that’s what gave the region’s bluegrass such vibrancy. Beyond categories lay personal dimensions: certain bands and musicians were like oil and water. The production committee faced artists’ and fans’ differing perspectives, values, and priorities. Terms bandied about during production meetings included “First Generation, Second Generation, Urban” and so on.

Another planning challenge: the concert featured some working bands, each on their own professional trajectory. But as a reunion it also featured retired individuals and groups.

The final concert performance sequence reflected our work to keep tension levels low, make things flow, and illustrate the artistic collaborations that had come out of this cultural scene.

My primary task was writing the introduction for the program, seeking to explain why CityFolk was presenting hillbilly music as heritage.

I was assisted by Barb Kuhns and Larry Nager, who were writing artist bios and gathering illustrations for the program. Musician and producer Nager knew the history from the inside, as his chapter, “Sing Me Back Home: Early Bluegrass Venues in Southwestern Ohio” in Industrial Strength Bluegrass (pp. 77-100) attests. Kuhns, professional librarian and fiddler with the Corndrinkers, an old-time group, had been active in promoting the music of some of the lesser-known pioneers in the local scene of which she’d been part for many years.

With just over a month to go until the show in April, I spent a March weekend in Dayton helping the planning production staff finalize concert details.

In early April CityFolk sent news to the press of the coming event. “Dayton show will reflect Kentucky bluegrass roots” was the title of a 12-paragraph story in Sunday’s Louisville Courier-Journal, Kentucky’s equivalent of the New York Times. On Wednesday, the Dayton Downtowner, a weekly, carried two stories, and on Friday the Dayton Daily News (a supporter of the event) ran two generous stories.

On Friday night April 22, 1989, each of the concert goers who filled Memorial Hall — a Beaux-art national historic site (1907) of 2500 seats in downtown Dayton — received a 16-page 8 ½ x 11 program. Its cover duplicated the concert’s posters.

On the first page was Phyllis Brzozowka’s introduction. Next, an essay by former Dayton newspaperman Tom Teepen, who told the evocative story of his experiences with the music in Dayton.

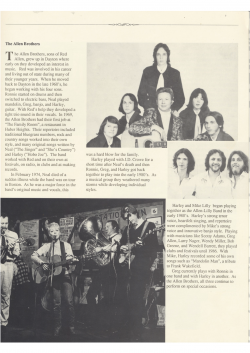

My piece, “Industrial Strength Bluegrass,” filled the next four pages. Then came seven photo-packed pages devoted to “The Artists”: Paul “Moon” Mullins and Traditional Grass, Noah Crase and the Valley Ramblers, The Hotmud Family, The Allen Brothers, Red Allen, The Dry Branch Fire Squad, Larry Sparks and Wendy Miller, Frank Wakefield, David Harvey, and the Osborne Brothers.

The booklet closed with several pages of lists: a “Selected Discography” including addresses for local and national retailers; planning production staff; thanks for assistance; CityFolk staff; board of trustees. Its endpapers were a map of southern Ohio, with portions of Indiana, Kentucky, and West Virginia. A lot to look at while waiting for the curtain to rise!

Behind the curtain, Baker’s Lime Kiln workers provided lighting and a stage manager. I was part of the backstage crew. And the sound was something else! Afterwards Phyllis wrote:

Pete Reineger, from the National Council for the Traditional Arts and a local crew…ran an equivalent of 4 stages with 36 open microphones throughout the performance.

I have been unable to locate any recordings of this event — no tape, no video. I saved a copy of Baker’s stage directions, which lay out the concert’s sequence. But Larry Nager’s script for his narrative, which told the history of Dayton bluegrass in seven segments, one for each act, no longer exists. In it, he recalled, Don’s role was that of “the omniscient voice of the hillbilly diaspora.”

Though the Dayton Bluegrass Reunion is now a lost play, its structure can be seen from Baker’s stage directions. However, because I was busy bustling around backstage, I didn’t know how the concert was going over with the audience until later.

The reunion began with an introduction by Phyllis, following that came sounds from offstage, described in the stage directions as:

Halsey & Meyers Commercial

Radio Rap — Moon Mullins.

Halsey Myers is still a going concern. Joe Mullins says that the Traditional Grass, the band he worked in with his father Moon from 1983 to 1995, recorded a radio commercial for this Middletown hardware store. It was so popular they got requests for it at personal appearances. Joe and his son Daniel found an old cassette recording of the ad followed by an example of Moon’s colorful on-air WPFB persona:

These radio clips would have been familiar to many in the audience who knew the local bluegrass scene. Paul “Moon” Mullins was the true loquacious voice of Appalachian migrant music — bluegrass — in southwest Ohio.

As the curtains opened Baker took the stage to tell the story of Mullins and the music. Photos synced to the script appeared on a screen behind him. Some were of Dayton musicians and venues, while others evoked a variety of historical and geographical milieus ranging from Dayton to national and international.

Baker’s light dimmed and focus shifted to the other side of the stage, where Mullins and his band, The Traditional Grass, were highlighted. Mullins had come to Dayton from Kentucky in 1964 to take a job as a DJ at WPFB, a Middletown country station that had been a bluegrass center in the 40s and 50s. Jimmy Martin, the Osborne Brothers and many others had performed there. The short-lived Martin-Osborne band’s hit trio “20/20 Vision” from those days is recreated by Dan Tyminski on the new Smithsonian Folkways album, Industrial Strength Bluegrass:

In the mid-’60s WPFB had dropped bluegrass but Mullins brought it back. He’d started his radio and musical careers (he’d fiddled with the Stanley Brothers) in eastern Kentucky. Migrant audiences in southwestern Ohio bonded with him. He revitalized the music at WPFB and began playing with local bands.

I first saw his name in June 1968 when we were both on the flyer for Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Festival at Bean Blossom, Indiana. I was in the banjo workshop (with Ralph Stanley, Dave Garrett, Bobby Thompson, Vic Jordan, and Larry Sparks); “Paul Mullins, WPFB Radio, Middletown, Ohio” was emcee for the Saturday shows, co-hosting on Sunday with Grant Turner of the Grand Ole Opry.

Twenty-one years later, on the evening of the Reunion, Mullins had recently left WPFB. He’d started The Traditional Grass in 1983 (they would continue until 1995); it included his son Joe, who was singing tenor, picking banjo, and following his dad’s footsteps in radio. Guitarist Mark Rader was the lead singer, and Glenn “Cookie” Inman, bassist. They opened with “Weary Lonesome Blues,” a popular Delmore Brothers song from 1937:

After three more songs, everyone except Moon left the stage and he was joined by members of The Valley Ramblers, a band he’d co-founded with Noah Crase in the late ’60s. Crase was a highly respected banjo player, a former Blue Grass Boy best-known for “Noah’s Breakdown,” the tune that started Bill Keith on his exploration of melodic banjo.

Editor’s note: Read part one of Industrial Strength Bluegrass and the Dayton Bluegrass Reunion here

Neil V. Rosenberg would like to thank Barb Kuhns, Daniel and Joe Mullins, and Larry Nager

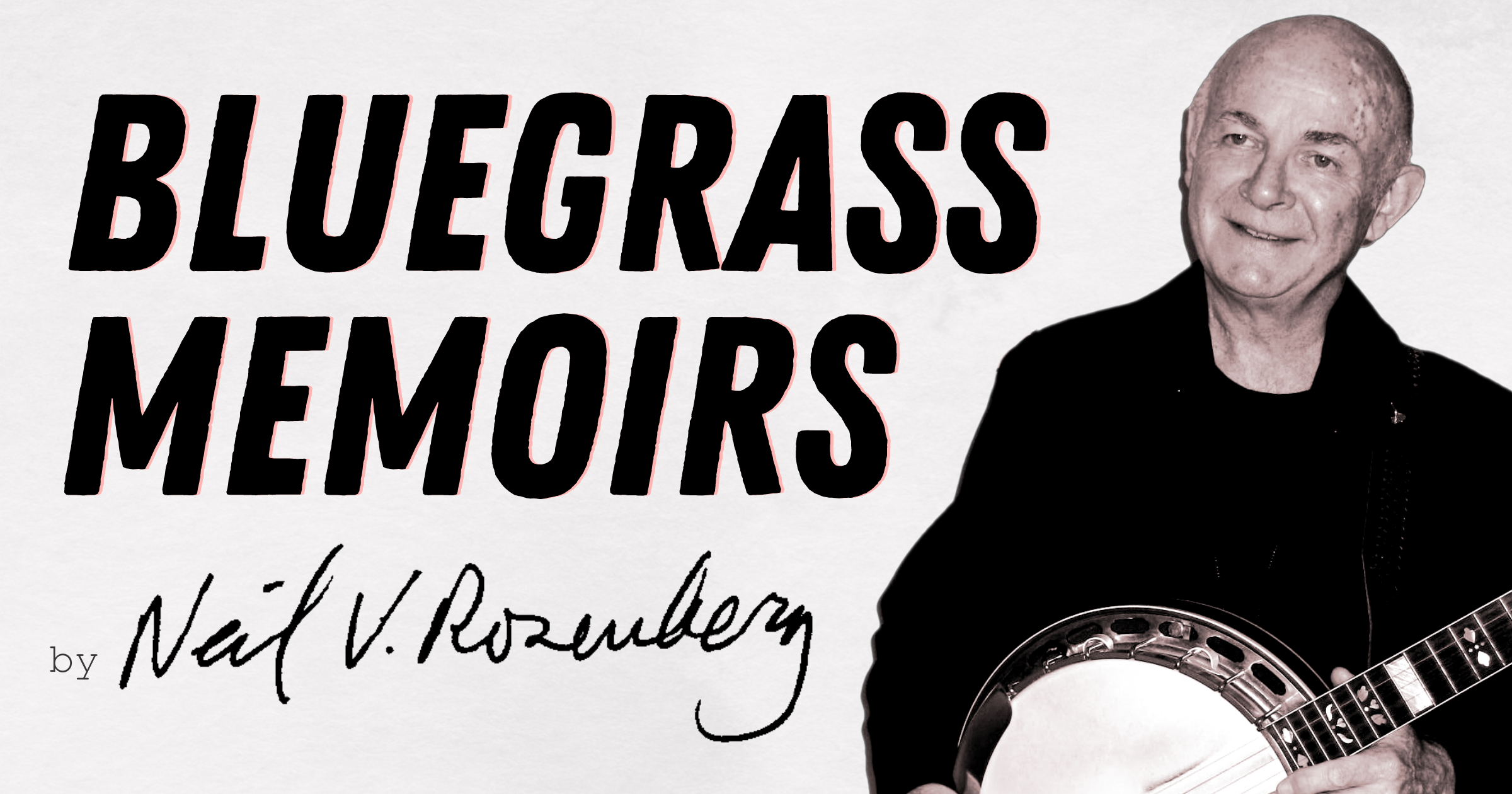

Rosenberg is an author, scholar, historian, banjo player, Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame inductee, and co-chair of the IBMA Foundation’s Arnold Shultz Fund.

Photo of Rosenberg: Terri Thomson Rosenberg