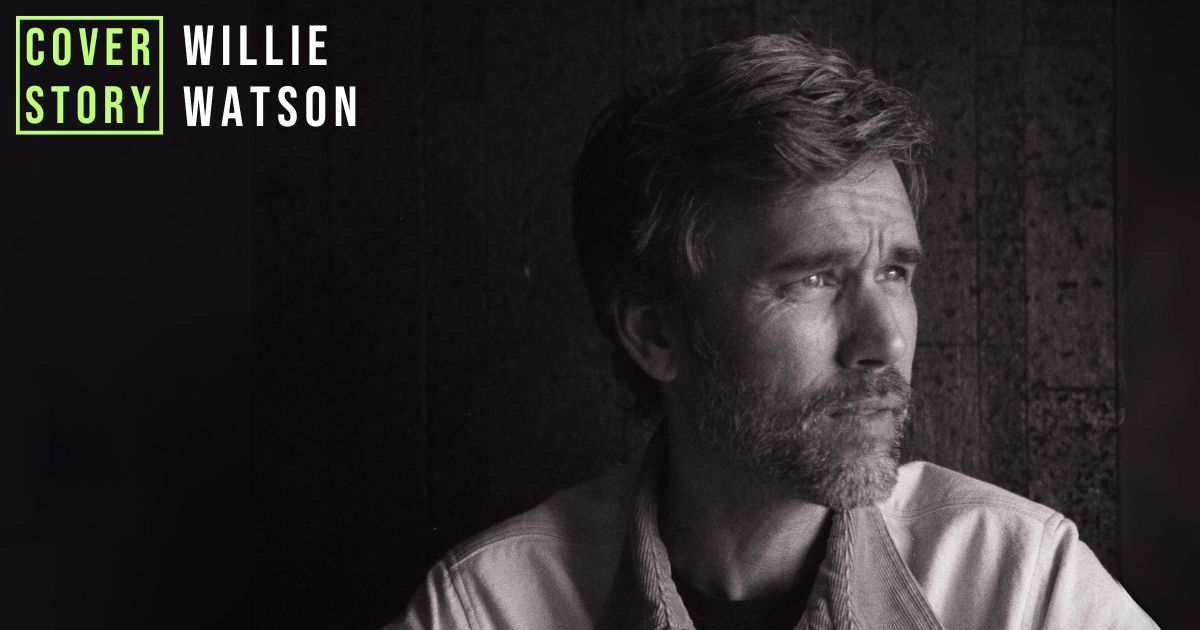

Willie Watson has been a solo act for well over a decade, since leaving Old Crow Medicine Show way back in 2011. And while he’s put out records since then, in many ways his self-titled third release marks a new beginning. A lot of that comes from the fact that it’s Watson’s first solo work with original material, following two volumes of Folk Singer albums drawing from The Great American Folk Song book.

Watson worked with a co-writer on the original songs on Willie Watson, Morgan Nagler from Whispertown 2000, and the results sound like the sort of songs you’ll hear traded around folk festival campfires for years to come. The co-production team of former Punch Brothers fiddler Gabe Witcher and Milk Carton Kids guitarist Kenneth Pattengale capture the tracks in spare, elegantly understated arrangements with the spotlight firmly on Watson’s voice.

The album begins with a literal trip down to hell on “Slim and The Devil” (inspired by 2017’s white supremacist riots in Charlottesville, Virginia) and ends with “Reap ’em in the Valley,” an autobiographical talking gospel about Watson’s own long, strange trip. In between are songs about love, fear, the occasional murder. One of them is another cover, Canadian folkie Stan Rogers’ stately “Harris and the Mare,” and you’ve never heard a song that’s both so beautiful and so horrific.

BGS caught up with Watson on the eve of his album’s release.

So after so many years playing old folk songs, what got you into writing your own?

Willie Watson: I’ve always written songs, but never thought of myself as a “real” songwriter, like Gillian Welch or Dylan or Ketch [Secor]. That just didn’t seem like what I was engineered toward. I wanted to be that kind of songwriter, but told myself I didn’t measure up. So I got into traditional music. When I’d get together with friends at parties, I’d be more likely to sing songs that were traditional or someone else’s. Being in Old Crow was great, because I got to write with other people, mostly Ketch. Co-writing was easier on me.

Once I found myself on my own, I was very scared to write by myself. Being completely responsible for everything is scary and for whatever reason I could not bring myself to do that. Now I understand that no matter how simple, complicated, mature, childish or anything else I put into a song might be, it’s okay. I don’t have to tear apart and criticize, say terrible things about it before I’ve even written it down on the page. Left on my own, that’s typically what I’d do. It’s only now at age 44 that I can get past that. What a long road.

Do you remember the first song you ever wrote?

“Roll On” when I was 15 or 16. It was wintertime at my house in Watkins Glen, late one night when everybody else was asleep. I went out to smoke in the back yard and it was quiet. As I looked at the nighttime winter sky, I had this story come into my head about a cowboy in an old town. I wrote the words out quick, almost as I would have been playing it. Just looked up at the sky and thought of it and it washed over me fast. It was a pretty powerful first song, but I ignored it and have the most regret about that. For whatever reason, there was something in my life that made me not give it enough credit.

How did you connect with your co-writer, Morgan Nagler?

She’s a great songwriter who has made a few records, does a lot of co-writing with people you know. You’ve heard songs on the radio that she co-wrote. I was afraid to sit down on my own and write, and Dave Rawlings said I should call her. I was apprehensive about presenting ideas and words and parts of myself to a person I didn’t know, but it was immediately fruitful. The first day, four hours later we had a song I really liked, “One To Fall” – it’s on this record. That we came up with something I felt strongly about right a way got me fired up, so we kept going. Every time we got together we wrote a good song.

What was it like to appear in the Coen Brothers movie, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs?

It was amazing. They had me audition for another movie I did not get the part for, but they already had me in mind for the one after that. But it was terrifying. Little cameras scare me enough and the big gigantic ones are even scarier. Like a gigantic eye and you’re not supposed to look at them even when they’re right in your face. I’m no actor. I knew my lines, but did not know what to do. I called Joel [Coen] a month before to ask if there was anything he could tell me to prepare me. “The only thing I’ll tell you is your first instinct is probably right,” he said. Which didn’t help at all. On-set, I was still scared. I had to learn to get on the wrong side of the horse because of the camera shoot, which was awkward. So I was not knowing what to do until they took me to wardrobe. Once I had on the costume and the hat and looked in the mirror, I suddenly knew exactly what to do. When I saw how I looked, it all made sense: Just go out and be Clint Eastwood.

Fear, even terror, seems like a recurrent theme in your life as well as your work.

It’s a recurring thing for every human, if they’ll admit it. It’s so freeing to admit I don’t know what’s going on, I’m scared, I need help. So much of the time I’ve done the opposite and gotten nowhere. The only person making my life hard was me. Touring with different people, I see them get into stressful situations and I think, “It must be hard to be them today.” I was just like that for a long time, tearing through things everywhere I went. I was afraid and my way of dealing with that was to try and control things. A lifetime of that proved disastrous.

I got to the point of trying other things and eventually learned about humility. That started me changing and growing and recognizing that the only reason I made my life so hard was being afraid of everything. It’s so risky doing this and I am scared of it. I’m apprehensive about even saying that. The public wants you to be confident onstage and I am that. Sometimes not, though. It’s hard to put it out there and not be afraid. I’m gonna cry a lot in front of people onstage, and that’s brave and good for me. This record is me understanding that there’s power in those uncomfortable moments, and embracing them. There’s a lot of healing in being able to go ahead and do that.

Who are you dancing with in the video to “Real Love”?

That’s my wife Mindy and the song’s about her. Once we got together, it went quick with us. But there was not romantic interest when we met, we were just working together. She’d quit her job as a fast fashion designer wanting to do something fun, cool, more fulfilling. A mutual friend was trying to get us together, knowing she was interested in getting into denim work and that’s what I do. The friend knew I needed help. So she started as an apprentice, got good fast, and we ended up working together. For a year we sat and sewed together and became best friends, she’s the best I ever had.

I was careful about that relationship, didn’t want to ruin it. So that song’s about how it started and what it meant, how true our love feels. It outdid everything else I’ve experienced my whole life. It shows how every other relationship I’ve ever had, I wanted the wrong things and, I daresay, they all wanted the wrong things from me, too. It went both ways. I’m not even talking about romantic love. It ends up being about everyone in my life. The story of my love life is the story of my life, love in all its forms. It’s a bold statement that she is the only real love in my life so far.

How did you come to know Stan Rogers’ “Harris and the Mare”?

I’m a Stan Rogers fan and that song comes from Between The Breaks, a live album recorded at McCabe’s in Santa Monica. I was thinking, “Do I want to put this on a record with my songs?” I’d written simple rhymes, couplets that are almost kinda childish – and I’m gonna put them next to a well-crafted song by a master songwriter? But Kenneth and Gabe had heard me sing that one at shows for a while and really wanted it on tape, and I guess I did, too. And after the recording came out so awesome, how could it not be on the record? I found out it did tie into my life. We made this record and I was unsure if any of it made any sense. Once it was sequenced and I lived with it for a month or two, it came into focus. That’s a violent song about a man who doesn’t want to be angry and violent. And I’ve been that man in my life. I relate to this guy.

The other cover, “Mole in the Ground” – did you know that one from Anthology of American Folk Music?

Yes. I love Bascom Lamar Lunsford, he’s so weird and interesting to listen to. Those old recordings, I can’t listen to a lot of Carter Family or Blind Willie McTell. Three or four songs and I don’t want to hear more. But Bascom, I can listen to a good 30 minutes and that says a lot. Like “Harris,” that was a big puzzle piece where I was unsure how it would fit. What made it were the string arrangements. That tied it in with “Harris” and “Play It One More Time.” Gabe directed the string arrangement, but let them find their own way. It was a cool every-man-for-himself arrangement.

The closing song, “Reap ’em in the Valley,” really tells a lot about how you came to be who and where you are, describing an early encounter with a singer named Ruby Love.

I’ve always talked too much at my shows. But being alone onstage, I had to find ways to make it more interesting. Switching from guitar to banjo is a great tool in the arsenal, but people still got bored of that. Folk singers traditionally tell stories and lead sing-alongs. So I learned how to talk to people in a real personal way about mundane things, relating our lives to find common ground rather than tear each other apart. Just me up there, whether it’s in front of 15 or 50 or 1,500 people, it becomes a battle if it’s not working. Me against them. Sometimes it was a disaster, when I was not speaking from experience or the heart, places I knew. But once I started telling stories about me simply walking down a country road, they’d perk up and listen. So I became a storyteller. I figured I’d put one on this record, and that was one Kenneth and Gabe really wanted me to do.

I hope it translates. It’s my experience of looking back at evidence of what I call God in my life, how you can’t deny it. What I am now, Mr. Folksinger. That’s what people recognized me as, the place I ended up. It could have gone differently, but this is what I’m here for. Those impactful moments. I didn’t think much about Ruby Love over the years, until I started thinking more realistically and honestly the further I got from it. Meeting Ruby Love when my heart was so broken and how that felt, that’s what I never forgot about that night.

That’s the thing that stayed with the picture of it all, like a scene in a movie. That’s what vivid memories look like, movies. All that imagery rattling around my head. I relate a lot of that to the nature of God and God’s power in my head. It goes hand in hand with the moon and lake and sky, and how the moon affected Ruby Love. What Ruby Love did for that party and what the orchard did for his guitar.

Photo Credit: Hayden Shiebler