In 1971, Richard Nixon was president and the United States was divided. It was an era marked by civil rights struggles, Vietnam War demonstrations, and labor union losses. The counterculture movement that evolved in the 1960s was continuing to take shape and was intrinsically linked to the outpouring of a whole generation’s worth of musical innovation. Amidst social upheaval, at a time when your music reflected your politics, a common ground was forged among unlikely sources. The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s milestone 1972 album, Will the Circle Be Unbroken, single-handedly bridged generational and cultural gaps by pairing country music veterans with young hippies from Southern California.

“I don't think we realized the sociological impact that that record would have,” says Jeff Hanna, founding singer and guitarist of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. “On the surface, it looked like, 'What the hell are they doing making music together?'”

The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band formed in Long Beach, California, in 1966 and became a staple of the wave of California rock that included acts like the Byrds, the Flying Burrito Brothers, and the Eagles who were all exploring old-time country sounds in their own music. By the time the recording sessions for the Circle record began, the Dirt Band was fresh off the success of their cover of Jerry Jeff Walker’s “Mr. Bojangles,” which had become a Top 10 pop single. Record executives and fans, alike, were anticipating a follow-up in the same vein. But the band’s manger and producer, Bill McEuen — brother of band member John McEuen — had another idea: to get the band in the studio with the bluegrass and country musicians that had influenced them when they were coming up.

“I have a lot of respect for [the Dirt Band] for doing it, for going out on a limb, you know, and doing that kind of thing in the middle of a career that was just really on its way up at that point,” says multi-instrumentalist and longtime Dirt Band collaborator Jerry Douglas. “They were the famous people on the record and their guests were the people that they were introducing to their audience, you see. So it was kind of going out on a limb for them. You know, the record company didn't wanna do it. Nobody wanted to do it. They just kind of pushed it through and it was a success.”

When it came time to recruit a slew of Nashville greats for the project, the generational divide ended up working in the Dirt Band’s favor. Their friendship with the Scruggs family began when Earl Scruggs brought his children, who were fans of the band, to a gig they played at Vanderbilt University in 1970. Scruggs became the first artist they invited to guest on the Circle record. They snagged Doc Watson the same way: his son, Merle, was a fan of the band.

“One of the things that was really interesting with a lot of these acts is, their kids were fans of the band. There was kind of a stamp of approval from the younger generation,” recalls Hanna. “And Merle Watson said something like, ‘Well daddy you love the way they sing and play.’ And also the invitation was, ‘We've got Earl Scruggs.’ And Doc said, ‘Yeah, that sounds like fun,’ so there it went.”

Other guests included heavyweights like Jimmy Martin, Mother Maybelle Carter, and Roy Acuff.

“I mentioned to Bill McEuen, at one point, that I'd read this article about Roy Acuff where he said he'd play real country music with anybody anywhere. And we talked about that and Bill said, ‘Well, let's see if he'll put his money where his mouth is,’” Hanna says.

But Acuff wasn’t an easy sell: His initial meeting with the band didn’t go as well as they were hoping. It turns out that the idea of West Coast hippies in their early 20s recording in Woodland Studios in Nashville was a bit of a hard pill to swallow.

“[Acuff] came in and he was just largely unimpressed with us. He was kind of like — he wasn't totally negative — it's just kind of flat and he said later, ‘Well, I don't trust a man that I can't see his face,’ and we all had like massive beards and mustaches and long hair,” Hanna remembers. “Meanwhile, we got in the studio and recorded our tracks with Merle Travis and, lo and behold, Roy Acuff comes strolling in, or sort of quietly walks in the back of the studio at the end of the day. And Bill played him — it was either ‘Nine-Pound Hammer’ or ‘Dark As a Dungeon’ — one of those. And Roy got this big smile on his face and he said, ‘Well, that ain't nothin' but country. I'll be here tomorrow. Be ready.’ So we cut those tracks, so he was in.”

The result was a monumental cross-generational album that combined genres and styles.

“Just to put it in context: You've got Merle Travis's Travis-picking; you've got Earl Scruggs' Scruggs-style banjo; you've got Maybelle Carter, Carter scratch; and Doc Watson — even though flat-picking isn't named after him, it should be,” says Hanna. “I mean, just all these guys that were just so big in our world.”

The Dirt Band’s love of country and old-time sounds goes way back, so it was a natural progression for them to want to honor and record with these musicians.

“A lot of us got into bluegrass because of the folk boom in the mid-60s. A lot of us also had older siblings and they'd bring home these records by Peter, Paul, and Mary or the the Kingston Trio,” says Hanna. “When I first started playing guitar, I bought a Pete Seeger instructional LP and book that had a section about the Carter Family and Maybelle Carter and her playing style, as well … I was a huge fan of the Everly Brothers. We all were. The Everlys, Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran, Chuck Berry, Little Richard: that stuff killed us. But I think something we all had in common was our deep love of the sounds of Appalachia. And blues for that matter. But a lot of it was acoustic music, I've gotta say.”

Singer/songwriter Jackson Browne joined the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band when he was 17 years old, after meeting them at a gig at the Paradox club in Tustin, California, a little town in Orange County. “Getting to play with them was a huge installment in my musical education because I got to sit there and play these really intricate songs,” Browne recalls. “I mean, they were all better players than me, so I learned a lot.”

What struck him immediately about the band, he says, was their vast musical palette.

“The Dirt Band was great because they were true music fans and music aficionados. They weren't just kids that were playing folk music that they heard. They dug deep, is what I'm saying,” says Browne. “They found recordings of the Memphis Jug Band and those things were hard to find. I mean, like that wasn't just lying around. And they were kind of musicologists even then, from the very beginning.”

This year, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band celebrated their 50th anniversary as a band. In commemoration, they returned to Nashville for a star-studded concert at the famed Ryman Auditorium last September, which aired on PBS and was released on DVD. Aptly titled Circlin’ Back, the show was both a nod to the first Circle record and a career retrospective that incorporated the musicians that have impacted the band’s history. Vince Gill, Alison Krauss, Rodney Crowell, Jerry Jeff Walker, John Prine, Jerry Douglas, and Jackson Browne were among the handpicked guests.

“What was even cooler to me than playing the show that night was the rehearsals that we had before,” Douglas recalls. “The first time you do a run-through of one of those songs is so magical. It has all of this extra spark and fear and everything in it. So there were sparks flying in the rehearsal hall when we were doing these things and trying to figure out who played on what.”

Just as the Dirt Band introduced their audience to their earlier influences on the first Circle record, the Circlin’ Back anniversary show connected the next generation of artists and fans together. Musicians like Vince Gill and Jerry Douglas, who remember buying the first Circle record when it came out, are now considered “little brothers” of the Dirt Band. Although they are each musical powerhouses in their own rights, the anniversary show was an opportunity for them to play with some of their heroes.

“I think the first time I played on the song with Jackson Browne that I played lap steel on, I held my breathe through the whole thing,” Douglas says. “I'm such a fan of all of those guys and then they bring Jackson Browne in, and I'm playing on this thing with Jackson Browne and I'm just going nuts inside. So much raw emotion that's happening.”

The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band has always had the ability to tap into emotion. Through their shared love of traditional music, they impacted legions of listeners by bridging generations and styles. Their legacy is littered with stories of parents and children bonding over the first Circle record, which is arguably one of the most significant releases in the history of music. At a time of cultural unrest, it showcased music’s ability to bypass divides and cross boundaries. The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band was Americana before Americana had a name, and their genre-bending illustrates the most important facet of music: how it connects us all.

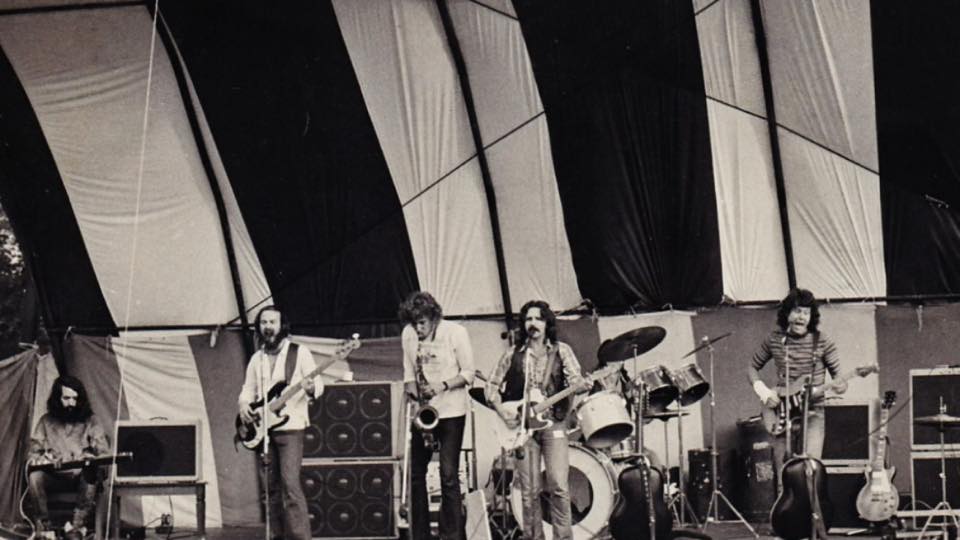

Photo of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band in the early 1970s courtesy of the artist.