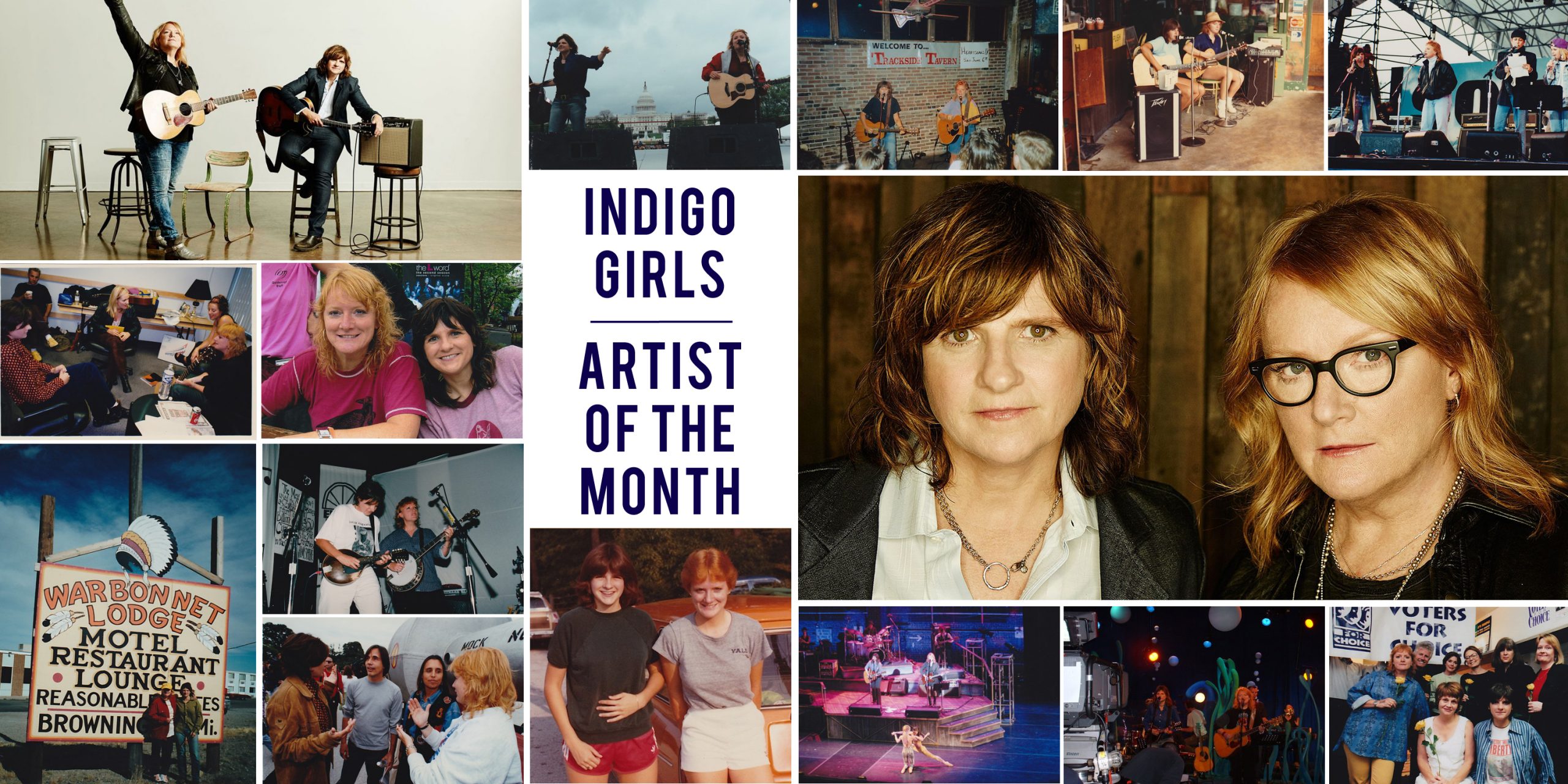

Although the earliest traces of Amy Ray and Emily Saliers joining musical forces date back to 1981 — and their original meeting back to 1974 — the Indigo Girls’ debut album, Strange Fire, was released in 1987. To mark the much-beloved duo’s 30th anniversary, we wanted to say “thank you” to Amy and Emily for everything they have given us over the years … the art and the activism, the influences and the inspirations. To do so, we reached out to artists who have walked the trail they blazed, starting with singer/songwriter Mary Gauthier, who penned this wonderful recollection that speaks for so many. (Keep an eye out all month for more artists paying tribute through stories and songs.)

Lesbian icons. When I was a kid, the mere thought of such a thing was laughable. I was growing up in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in the 1970s. There were no iconic gay women. Hell, there were no gay women, period. When I began to wonder if I was gay, I went to the library looking for lesbian authors. My research brought me to one book: Radclyffe Hall’s sad book, The Well of Loneliness. I read it, then landed on its predecessor, the bi-monthly mailed-in-a plain-brown-paper-wrapper-lesbian-newsletter, LC (Lesbian Connection). A nod to Hall’s 1928 book, the polite LC personals were called “The Wishing Well.”

LC introduced me to “womyns” music. I loved the great Canadian folk singer Ferron, but as an angst-filled, queer, ’70s teenager from the Deep South, I did not relate to much of the womyns music scene. I didn’t fit in there, either. I found myself listening more to Southern folk singers like John Prine, and other male songwriters whose words I felt close to.

Imagine my surprise when I moved to Boston in my early 20s and heard the Indigo Girls for the first time on WUMB college radio. There was SOMETHING THERE for me, personally — a brand new, yet deeply familiar sound. It resonated. I FELT it. Though I did not know it consciously, a part of me understood: Those voices were gay women from the South, like me. I parked my black Toyota restaurant truck in the driveway, turned the radio up loud, sat there stunned, and listened as the song played out. The sound infiltrated my soul. What was this, some kind of cosmic lesbian musical sorcery? Who were these people? They fucking rocked. The harmonies peeled back layers of scar tissue at my center, exposing a longing in me that I could not name. The song coming out of the radio was called “Strange Fire.” Hearing it for the first time in my truck that evening literally hurt.

I come to you with strange fire

I make an offering of love

The incense of my soil is burned

By the fire in my blood

Those harmonies landed like a déjà vu — utterly familiar, but not at all known. The sound was pointing me to something vital about myself, but I did not know what it was. The alchemy evoked a buried self I had not yet met, the future songwriter in me, entombed in a personal Pompeii, frozen under layers of active addiction. When the song ended, I turned off the radio, clenched the steering wheel, laid my head down, closed my eyes, and cried. I banged both hands on the wheel … harder, then harder still.

I was drunk, stoned, and tired of feeling alone. I had a hole in me that the call to songwriting had once upon a time tried to answer. But the call wasn’t even a memory anymore. I had put my guitar and musical longing aside, buried them both in a past I did not contemplate, and forgot about them. Women who did not (or could not) abide the compulsory rules of gender — the sexualized female appearance tailored to the male gaze — didn’t stand a chance in the real music business, right? I’d grown up, turned away from music. Made peace with 1 Corinthians 13:11: “When I was a child, I spoke and thought and reasoned as a child. But when I grew up, I put away childish things.”

I was a restaurateur now, a businesswoman, and a CEO. A chef. I established and ran several restaurants. I had what thought I wanted. I was young and successful. But I felt empty. There was money, but it didn’t matter. I’d spent the last decade subconsciously flirting with death. I lived with a gaping hole in the center of my being that I poured booze and dope and romance and success and any other thing I could jam in there to deaden the pain, the sadness of an unlived life. I was lost, careening the wrong way down a one-way street. I did not know how to turn around.

So I worked harder, tried to make more money, and became grandiose. Angry. I demanded that those around me work harder, too. We had to push the limits of what was possible. I was hoping to succeed my way out of the feeling of being lost. Somehow, the sound of that song on the radio saw me and called to me, but I couldn’t understand what it was telling me about myself. I could not make sense of the visceral response it released in my gut, even as the waves of emotion doubled me over.

A few months later, I was arrested for drunk driving. The court sentenced me to mandatory rehab. I got sober. Soon after, I decided to find the source of those magical voices I’d heard on the radio. I called the station, described the song, and the DJ said they called themselves the Indigo Girls. I went to Tower Records and bought the record, Strange Fire.

Amy Ray, Michael Stipe, Natalie Merchant, Woody Harrelson, and Emily Saliers perform for Earth Day in Washington, DC in 1990.

Soon after, I went to see them perform at the Paradise, a Boston rock club. It was 1990. I was a few months clean and sober, and what I saw that night made me dizzy, weak, and queasy. The mostly female audience was screaming the singers’ names, while crying and shouting the words to the songs, as the two women on stage sang smiling, delighting in the raucous, carnival-like excitement. In short, the fans were out of their fucking minds. The scene that night was like the black and white footage of girls screaming for the Beatles in 1964. For the first time ever, I saw women jumping up and down and screaming at the top of their voices for women. It was pandemonium. No Well of Loneliness here, this was a grand public display of woman-loving-woman energy, a giant wave of out-ness that rode the waves of the music being played on stage, blasting through the house speakers. It blew my mind.

I’d been out for years, so it wasn’t the queerness that freaked me out; it was something else. I could not name what was happening inside me, but I left early, after going into the bathroom, afraid I would literally be sick. My knees could barely hold me up. I was only a few months sober. I wasn’t even sure I saw what I had just witnessed. I was utterly confused. I loved the music, the passion, and the songs. What the hell was making me so queasy? I had no idea then that the pain of an unlived life was dropping me to my knees in the not-so-clean stall in the women’s room in the Paradise Rock Club.

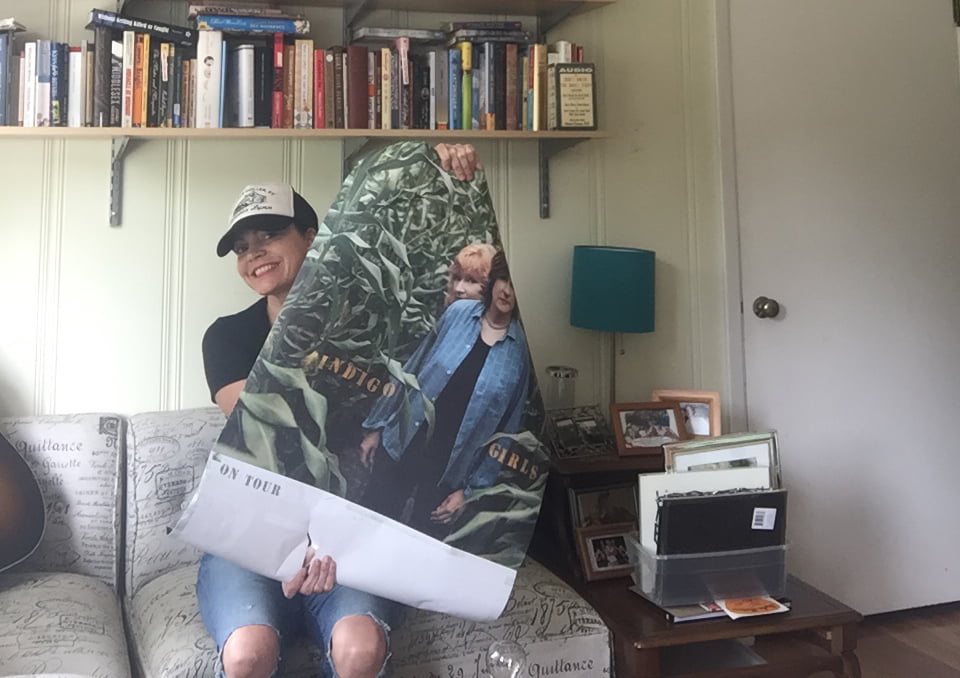

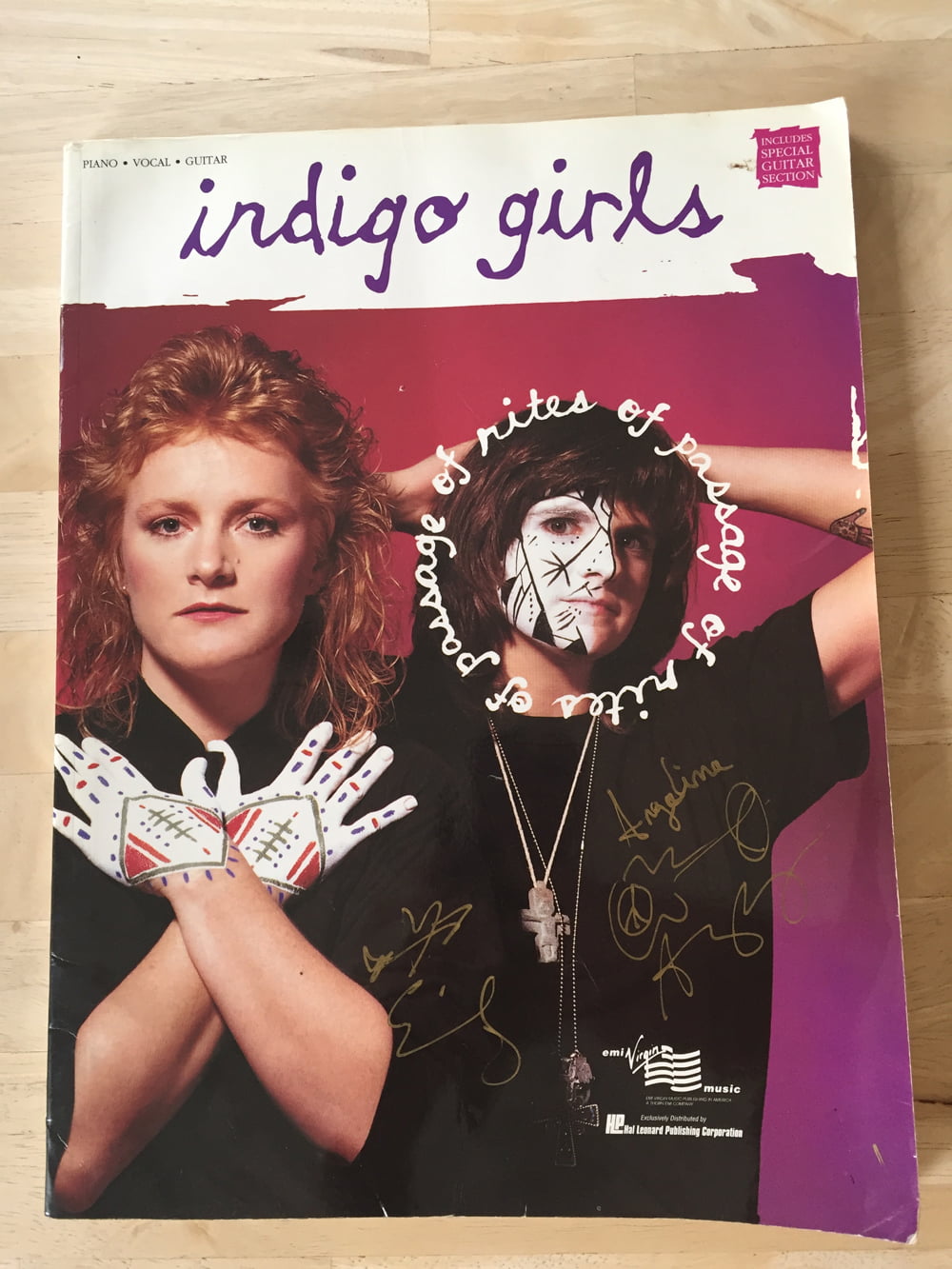

I went and saw them play again at the 1991 Newport Folk Festival. I’d listened to the Strange Fire record hundreds of times, and had just bought their self-named second record, Indigo Girls. The record had thrown off a smash radio hit, “Closer to Fine.” The Indigo Girls became Newport headliners the summer I celebrated my first year of sobriety. As a gift to myself, I bought a ticket to the festival.

The skies over Newport, Rhode Island, burst open with rain before the Indigo Girls took the stage, but I didn’t care. I found something to hold over my head. Maybe a stranger loaned me an umbrella? I don’t remember. What I do remember was the absolute joy I felt watching them with a full band, brilliantly and confidently take over the entire universe, as the rain came crashing down and rivers of water raced down the hill, magically splitting along both sides of my little island of safety. I had not felt joy like that since … maybe … ever.

Gone was the upset in my gut, the confusing angst, even though the heightened emotions in the women in the audience at Fort Adams State Park was like the Paradise Rock Club times 10,000. I was becoming one of the singing-along-out-loud fans. There were screaming, crying, lyric-shouting women as far as the eye could see and, this time, it made me smile. Song after song, women running up to the stage in tears reaching for them, while security had to push back the surge, while beautiful young girls threw themselves and their passionate, hysterical love at the women on stage. It was amazing. I was witnessing a seismic shift in American culture, and in myself.

The Indigo Girls went on to rule the Newport Folk Festival in the 1990s, appearing as headliners nine times in 10 years. They were stars and bona fide lesbian icons. I had no way of knowing that, a decade later, I’d be standing up on that very same stage myself. I was just beginning to feel the pull to my own music, to the old guitar that had sat in my closet for so long.

What I did know was that a door had opened. Things were different now, and weren’t going to go back to how it was before. The Indigo Girls had shattered the glass ceiling in music, the ceiling that no “lesbian-looking lesbians” had been able to smash through before them. Soon, lesbian artist after lesbian artist made their way through the opening the Indigos created. I become one of them.

I doubt I would have had the audacity to become a songwriter and take the stage without Amy and Emily laying the groundwork for up-and-coming artists. I owe them a huge debt and a heartfelt thank you. The spirit that flows through their music, and through all good music, contains much-needed truths that can help bring lost souls back home.

In their highest form, songs are vibrations from a higher world, which humans have been given the power to channel. Songs are a gift, an offering, and an open exchange between singer and audience. Songs are emotional electricity and know no sexual preference, gender, race, nationality, or age. Some are more than just sweet melodies or sellable entertainment products. The most meaningful ones are powerful medicines that can connect us to ourselves, each other, and to the divine. They carry emotional truths that burn through time and space, touching something eternal.

The songs of the Indigo Girls pointed me home to me, when I needed it most — a date with destiny, a divine decree. By being authentic, Amy and Emily have pointed millions of other people home, as well. Damn near everyone I know (straight and gay) has an Indigo Girls positive impact story. The world is a better, more inclusive place because of their music. So, I say with great joy, happy 30th anniversary to the Indigo Girls and to Strange Fire. You have done much for many, and we are better because of you and your music.

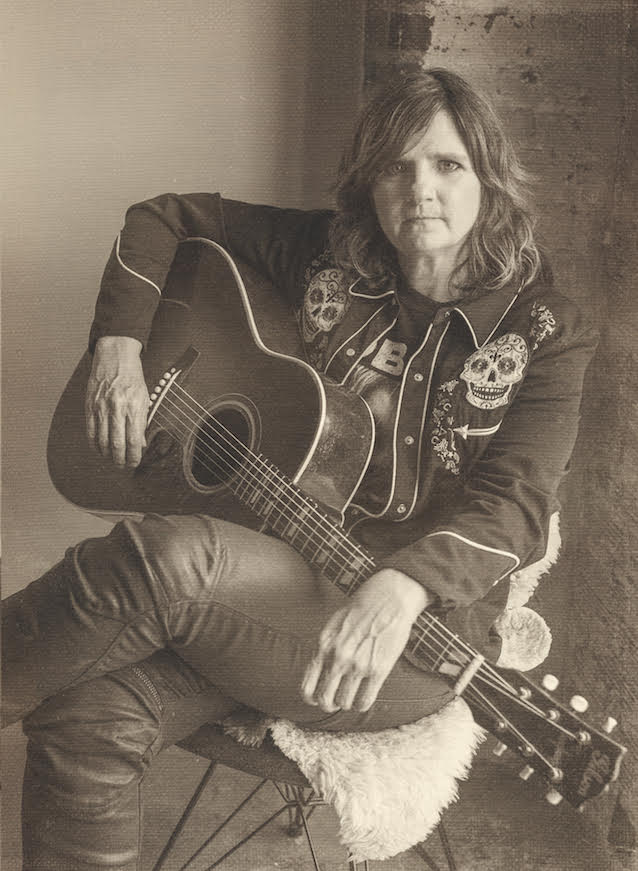

— Mary Gauthier

Photos courtesy of Indigo Girls