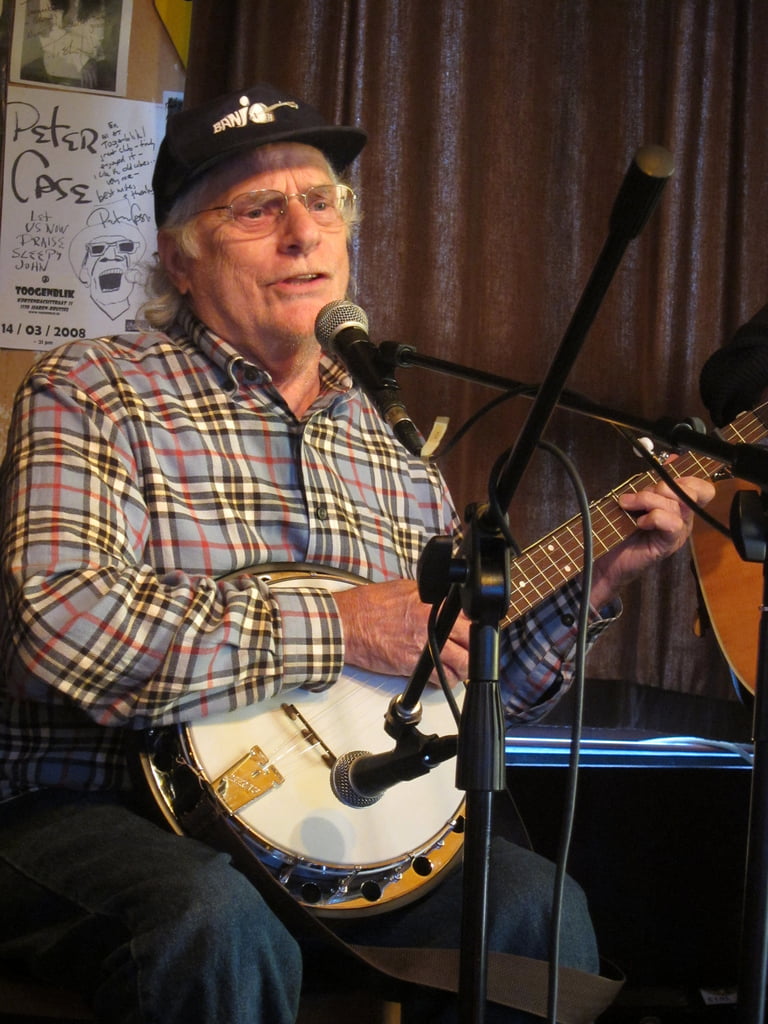

John Jorgenson is not only a man of many talents, he’s a musician with many interests. Perhaps you’ve heard his gypsy jazz, or remember when the Desert Rose Band — a neo-trad country group that included Jorgenson, Chris Hillman and other luminaries of the California country and country-rock scene — was riding high at radio, or perhaps you saw him playing an indispensable role in Elton John’s touring band. As Jim Reeves might have put it, he’s done a lot in his time.

Even so, you might not know that John Jorgenson is also a bluegrass guy — unless, that is, you saw him on the road with Earl Scruggs during the legend’s final touring years, or happened to buy his 2015 box set, Divertuoso, which included a disc of bluegrass alongside one of gypsy jazz and another of eclectic, electric music. Earlier this year, that disc was issued as a standalone album, From the Crow’s Nest. Featuring the regular (and equally eclectic) members of the John Jorgenson Bluegrass Band (J2B2) — Herb Pedersen, Mark Fain and Jon Randall — it’s a delicious collection that scatters well-known songs (Pedersen’s “Wait a Minute”; Randall’s “Whiskey Lullaby” co-write; and the Dillards’ “There Is a Time”) among a trove of newer material, much of it written or co-written by Jorgenson.

From the Crow’s Nest ought to go some distance in alerting wider audiences to a new standard-bearer for a style of bluegrass that, while its roots trace back to the early 1950s, hasn’t gotten the attention it deserves. Though Southern California is a long way from the Grand Ole Opry and other spawning grounds for the original bluegrass sound, it served in the post-World War II years as a magnet for job seekers from both sides of the Mississippi River, and that meant bluegrass pickers, too — and so, when we met up, that made for a good starting point for our conversation.

Listening to your album reminds me that you are a product of a Southern California roots music scene that included bluegrass from early on. How did you get exposed to it?

Probably the first time was when a band came to my high school and I thought they were from another planet, because I’d never heard anything so fast in my life. I played music already — I played classical music, and rock — but that was sort of an anomaly, and then I didn’t really see it again for a while.

I came to it sort of in a backwards way. I had a scholarship to the Aspen Music Festival. They brought me in as a jazz bass player; they wanted to start a jazz program. And I accepted the scholarship as long as I could also be in their classical program, playing the bassoon. Well, I had my tuition paid for, and my room paid for, but I didn’t have money for meals. So I needed to figure out how to make some money, and then I saw an ad that said: Wanted: strict jazz player for immediate gigs. So I checked out an upright bass from the school and went to this audition. And they weren’t playing jazz — what they were playing was David Grisman’s first album. This was the summer of 1978, so this album was new. I’d never heard it.

So they’re playing all instrumental stuff and I thought, OK, I really like the sound, especially of that mandolin. I liked the flatpicking guitar, too. I was already a guitar player, but I just loved the mandolin. When I got home that summer, my neighbors had a Gibson A model and I borrowed it. Not too long after that, I ran into a friend who had been instructed to put together a band that could play bluegrass and Dixieland to cover two different areas of Disneyland. And he asked, “Hey, do you know anybody that could play bluegrass fiddle and Dixieland cornet?” And needing a job at the time, I said, “I can play mandolin and clarinet.”

And then I kind of learned backwards, whatever I could. I learned from New Grass Revival, and then Bill Monroe, and Flatt & Scruggs, and the Stanley Brothers, and the Osborne Brothers. And all the others — Tony Rice, Sam Bush, the Bluegrass Cardinals, whoever was playing around at the time. Larry Stephenson was playing with the Cardinals at that time, and I remember I was — I don’t want to say shy, but I’m shy around people I don’t know. And to me at the time, they were real bluegrass musicians and I was a pretender. I sort of felt an attitude from some people, too, but he was not like that at all. He was really friendly.

Did playing bluegrass at Disneyland motivate you to build connections with the larger bluegrass scene, or was it a standalone kind of gig?

Actually, when we first started, we were terrible! We learned three songs and then we’d play those, move to a different place and play them again. But everyone was ambitious, so we all practiced; we learned songs, we got better. And then we started to play out around Los Angeles. I think the first time we played out as an act, we opened for Jim & Jesse at McCabe’s [Guitar Shop]. There was also a venue called the Banjo Cafe, with bluegrass every night, on Lincoln [Boulevard] in Santa Monica. So the Cardinals played there; Berline, Hickman & Crary would play there; and touring acts, too — Ralph Stanley would play there. And a young Alison Brown, a young Stuart Duncan.

I know that there are a lot fans of Desert Rose Band among bluegrassers, and some gypsy jazz fans, too, but for a lot of people, you came onto the radar when you were going places with Earl Scruggs — 15 years ago, maybe? How’d that come about?

Actually, it was because of Brad Davis. He was playing with Earl, and we were kind of guitar geek friends. We ended up sitting next to each other on a plane one time, and were chatting, and he said, “I’m playing with Earl Scruggs,” and I said, “I’d love to do that.” He said, “You know, they like to have an electric guitar, maybe there might be a spot.” He really set that up for me.

I said, “OK, I’m happy to play electric guitar, but I would really love to play the mandolin.” So I would bring both, and if I played too much mandolin, Louise [Scruggs] would say, “John, don’t forget that electric guitar.” Then they said, “Don’t you play saxophone? We used to have that on a song called ‘Step It Up and Go.’” So I said, “What about the clarinet? It’s not quite so loud.” And as it turns out, Earl said his favorite musician was Pete Fountain, and he loved the clarinet. So every time after that, Gary Scruggs would call me up: “Dad says don’t forget the moneymaker.”

The J2B2 record was originally part of a box set — a disc of gypsy jazz, one of bluegrass, one of electric stuff. So you have these different musical itches, and some musicians would choose to try to synthesize these things into something new and different and unique, but you seem to have an interest in keeping them each their own thing. Why is that?

It’s because, to me, the things that I love about bluegrass are what make it bluegrass. I love the trio harmony, I love these instruments, the way each instrument functions in the band. And I love gypsy jazz, and some folks might say they’re closely related — they’re string band music, they both have acoustic bass and fiddle and acoustic guitar, and each instrument has a role. There are a lot of similarities, but the things that I like about each one are what make them different. I think each music has an accent, and a history and a perspective, and I really want to be true to those, because those are the elements that touch my heart.

I feel like what I do and what this group does is quite traditional, compared to a lot of people. It’s not jamgrass. It’s not Americana. It’s bluegrass. There are folk elements, and all those other things, of course. But really, my touchstones for that style of music are all the classics: the trio harmonies of the Osborne Brothers, and the slightly softer Seldom Scene and Country Gentlemen sounds, the early Dillards, the Country Gazette, and the whole Southern California sound… you don’t think of Tony Rice’s roots as Southern California, but they are.

And probably at one point, if I could have sounded like I was from Kentucky, I wouldn’t have minded that. But at the end of the day, well, I love Bill Monroe as much as the next guy, and I’m going to take inspiration, but I feel like I’m part of a lineage of bluegrass that’s just as viable as any other, and why not have that sound be a part of me?

Photo credit: Mike Melnyk