In 1965, a dejected Paul Simon went for an extended stay in England. When he returned home to New York toward the end of the year, he brought Anji with him.

Well, “Anji.” A piece of music, not a woman.

“Anji” — sometimes spelled “Angi” or “Angie” — was written and first recorded in the late 1950s by English guitarist Davy Graham, considered by many the first star of the U.K. folk guitar renaissance. It’s a snappy little fingerpicked number, a series of trills over a descending bass line. Really more jazzy than folkie. By the time Simon first heard it, apparently via the playing of another young star of the scene, Bert Jansch, it had become the touchstone for English acoustic guitarists. This was the piece they had to master to gain entry into that world and in the process serving to popularize the dark modal DADGAD open tuning as the scene standard.

Simon’s recording of “Anji,” with the writing credit originally going to Jansch before later being corrected, served as an instrumental interlude at the end of side one of The Sounds of Silence, the second album he made with Art Garfunkel. But in the context of the sweep of Simon’s eventual status as one of the modern era’s supreme songwriters (and Simon and Garfunkel’s standing as one of the key pop acts of the 1960s and ‘70s), “Anji” marks a turning point.

“One of the things he found [in England] was a welcome, warm music community,” says Robert Hilburn, author of the new biography Paul Simon: The Life. The book is a comprehensive and colorfully enlightening look at the artist, done with his full cooperation. It was published in May, on the eve of what he says will be his final full concert tour. He’s named it the “Homeward Bound” Tour, after a song he wrote while in England.

“He hadn’t felt accepted in folk circles of America — Greenwich Village put him down because he came from Queens,” says Hilburn, who was the pop music critic and editor at the Los Angeles Times for more than three decades (and with whom this writer worked for more than 20 years). “But there, he was from America and people listened to him and liked him. And he said that the folk clubs in England were generally away from the bars and people listened to the songs. In America they were in bars and people chatted and ignored the music.”

Simon was feeling that rejection acutely when he moved to England. While Simon and Garfunkel had been signed to Columbia Records by tom Wilson after some furtive steps under the name Tom & Jerry (and some solo Simon work under the name Jerry Landis), their debut album, the acoustic folk-tinged Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M., had flopped and the partners were at odds — a common state through their lives. In England he found something to give him new artistic life, new purpose, a setting in which he could define his own goals and ambitions, and in which he was valued.

He released a 1965 solo album featuring acoustic performances of his own songs (The Paul Simon Songbook, not issued in the U.S. until its inclusion in the 1981 Paul Simon: Collected Works box set), co-wrote with Australian-born musician Bruce Woodley (including the bouncy “Red Rubber Ball,” a 1966 hit by the band the Cyrkle) and produced an album by fellow American ex-pat Jackson C. Frank, including the song “Blues Run The Game.” (Simon & Garfunkel recorded the song as well.) The composition became another standard of English folkies and later came to mark the tragic life and death of its writer. In the process, Simon discovered key things about who he was, and who he wasn’t, as an artist.

“Most of those musicians there were guitar players and played old folk music,” Hilburn says. “They didn’t write as much of their own. He couldn’t play guitar like they did. Martin Carthy [another rising star of the scene] was particularly helpful in teaching him things, but he realized that it was words that would distinguish him. That’s what the other English musicians wouldn’t do. He wasn’t a fan of the old-time English ballads. When he heard Dylan, he said, ‘That’s what I want to do, write about the world today, not just “I went down to the river and killed my baby.”’”

Now, to be fair, those “down to the river” ballads were just as much core to the American folk revival as the English one. But by and large they originated in England and elsewhere in the British Isles and Europe. The songs of murder, treachery and heartbreak arrived on these shores with the many waves of immigrants, mutating in various ways but still very recognizable in the forms associated with Appalachia and the Delta, bluegrass and blues alike, Cajun and country, you name it.

Of course, that all found its way back across the Atlantic where American folk and blues (and, of course, rock ’n’ roll) influenced and inspired a generation of English musicians looking for meaning and authenticity, even if borrowed, first in the “skiffle” movement, and then in both the folk revival and with the Rolling Stones, the Animals, of course the Beatles and the others who, in the mid’60s British Invasion, brought blues back to America.

Davy Graham was heavily influenced by American blues and jazz, and his early ‘60s albums were full of his arrangements drawn from that repertoire. And one of Graham’s frequent collaborators, singer Shirley Collins, traveled through the South in 1959 with American folk and blues collector and preservationist Alan Lomax, researching and recording the music on porches, in churches and prisons and at social occasions, documenting various forms that were threatened with extinction in the face of “progress.”

It is, in fact, a blues song that kicks off the upcoming Live in Kyoto 1978 concert recording by English folk great John Renbourn, who passed away in 2015. Renbourn, who in addition to his own long and fruitful solo career co-founded the revolutionary jazzed-up folk band Pentangle with Jansch, started this show with a version of “Candy Man,” a raunchy ragtime tune first recorded by Mississippi John Hurt in 1928. But the second song of that concert? Yup. “Anji,” with an introduction by Renbourn explaining that it was a “tune that started me, and a lot of other people, trying to play the guitar.” The album is a wonderful slice of a remarkable career from a stellar guitar talent who regularly tied together Medieval Italian and French dance tunes with American blues and jazz, all fixed around the English folk traditions of such songs as “Banks of the Sweet Primroses.”

It’s the Circle of Folk.

And it circled back when Simon found himself moving home to New York due to an unexpected turn of events. While he was in England, producer Tom Wilson — without Simon’s knowledge — added some folk-rock instruments to the acoustic version of “The Sound of Silence” that had been on the S&G debut. Suddenly it was the right song at the right time, a perfect fit alongside the Rubber Soul Beatles, the sparkling folk-rock of the Byrds and, of course, the newly electrified Dylan himself. That new version became both the title song of the next album and the launching point for new approaches that would quickly distinguish the duo.

How did the time in England make an impact, aside from “Anji”? Hilburn sees little direct evidence of the English folk scene on Simon’s writing, though there’s certainly some of the mood and filigrees of the guitar styles in the fingerpicked lines of “April Come She Will.” And there is “Scarborough Fair,” an actual English folk song that Simon took almost note-for-note from Carthy’s arrangement into an unlikely pop hit, its refrain providing the title of the third S&G album, Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme.

Carthy has said he was “thunderstruck” when he saw the song credited as “words and music by Paul Simon” on the original S&G release. Later it was discovered that while royalties were paid, the money was never forwarded to Carthy by his publisher. Simon years later made sure that new payments were made to the English artist, an act Carthy deemed “honorable” per Hilburn’s account.

But it remains a controversial episode for some, presaging later controversies of proper crediting and cultural appropriation that saddled Simon, particularly regarding his Graceland work with South African musicians at a time of a cultural embargo due to the countries brutal apartheid policies. (And, for Carthy, it was a second case of an American artist nicking one of his arrangements, as Dylan himself used Carthy’s version of the traditional “Lord Franklin” for “Bob Dylan’s Dream.” In addition, “Scarborough Fair” was liberally adapted into “Girl From the North Country,” with the source noted readily in the liner notes of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan as well as in various interviews by Dylan over the years. A duet by Dylan and Johnny Cash made for a highlight from the later Nashville Skyline album.)

If the direct impact of what he learned in England was not an ongoing presence in Simon’s writing and performance, it did seem to stimulate a hunger for exploring music from various cultures and countries, which soon emerged in a variety of ways — the Andean folk-tune on which he based in “El Condor Pasa” (in turn making it virtually inescapable for later travelers in Peru), reggae in “Mother and Child Reunion” (recorded in Kingston with Jamaican studio mainstays), and gospel in “Love Me Like a Rock.” Then he took that giant leap into South African music with the landmark Graceland album in 1985 and various Afro-Brazilian and Latin American inspirations and collaborations on Rhythm of the Saints in 1990, profoundly the batucada drumming on the song “The Obvious Child.”

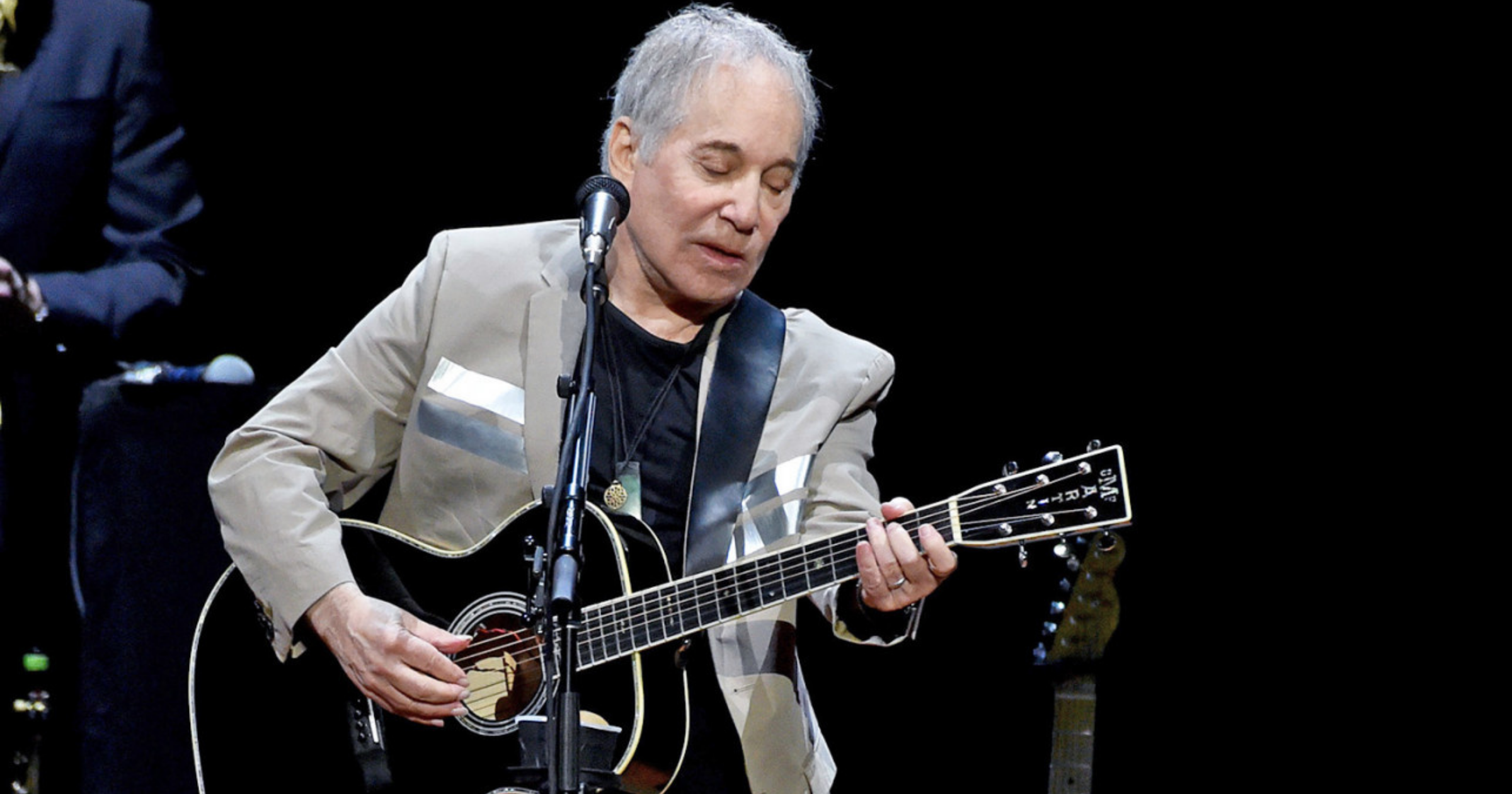

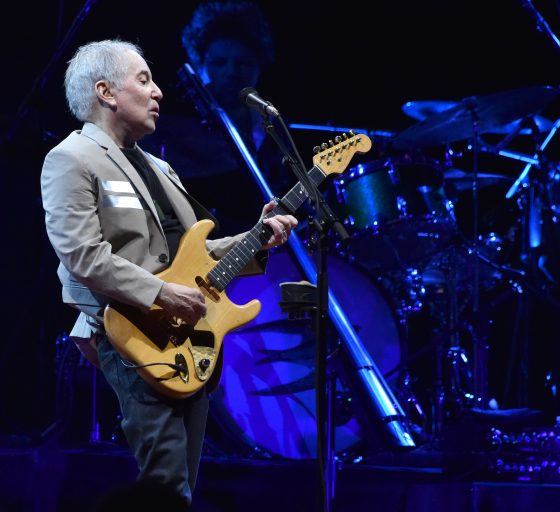

And, with this all in mind, it was striking during one of Simon’s Hollywood Bowl shows on his farewell-ish tour how well the song, “Dazzling Blue,” which had been on the 2012 So Beautiful or So What album, could have fit alongside many things done by Graham, Jansch and Renbourn. In this performance, Simon’s fingerpicked figures and lilting melody were weaving through the Indian-derived rhythms and modes carried in Jamey Haddad’s ghatam (clay pot) percussion and the veena-like melisma of Mark Stewart’s slide guitar. Ultimately it’s all of a piece, the band on this tour anchored by South African bassist Bakithi Kumalo, who has been Simon’s partner on much of the music he’s made from Graceland on. Young Nigerian guitarist Biodun Kuti steps in with grace and aplomb to the hole left by the death last December of Cameroonian musician Vincent N’guini, who had been with Simon since Rhythm of the Saints. But still the music is threading back to the epiphanies of London in the ‘60s. And yes, even Greenwich Village.

“He loves roots music,” Hilburn says. “What was interesting to me is that as a songwriter he doesn’t come up with a theme first. If you or I were writing a song, we might go, ‘Let’s write about ecology, or about breaking up with a girlfriend.’ He lets the music inspire him, plays guitar or piano and if something sounds interesting, he thinks, ‘What do those notes mean to me?’ and tried to put that into words. One line, then to the next line, and he discovers the theme as he’s writing. So he constantly needs new musical inspiration. He started with doo-wop and blues, then rock and folk. But by the end of 1969 he felt he couldn’t go any further in folk. He didn’t want to be part of that. So he goes to classical and jazz and gospel and bluegrass. And then South African music. He has to have fresh inspiration.”

Photo credit: Lester Cohen