While you know better, there’s a wide swath of the music-listening world in which Alison Krauss is best known as former Led Zeppelin golden god Robert Plant’s duet partner. Yet, Krauss has had a wholly remarkable career going back nearly 40 years, in which she has exhibited profound collaborative instincts and abilities.

On the occasion of the release of Arcadia, her first album with Union Station in 14 years (as well as a reunion with the founders of her former longtime label, Rounder Records), we look back at some of Krauss’ career highlights in and out of Union Station.

“Cluck Old Hen” (traditional; 1992-2007)

We begin with a literal oldie, “Cluck Old Hen,” from the pre-bluegrass era, which demonstrates two things – that Alison Krauss has always revered the history, roots, and traditions of bluegrass; and that Union Station is one incredible ensemble. Recordings of this Appalachian fiddle tune go back more than a century, to country music forefather Fiddlin’ John Carson in the 1920s.

Krauss first released an instrumental version of the tune on 1992’s Everytime You Say Goodbye (her second LP with Union Station), and won a GRAMMY with the onstage version on 2002’s AKUS album, Live. But feast your ears and eyes on this 2007 performance at the Grand Ole Opry, with a pre-teen Sierra Hull sitting in.

1992 studio version:

2002 live version:

“When You Say Nothing At All” (Paul Overstreet & Don Schlitz; 1994)

After a decade of steadily accelerating momentum, Krauss had her big commercial breakout with this AKUS cover of the late Keith Whitley’s 1988 country chart-topper. Krauss sang it on 1994’s Keith Whitley: A Tribute Album and it served as centerpiece of her own 1995 album, Now That I’ve Found You: A Collection. It reached No. 3 on the country singles chart and went on to win the Country Music Association’s single of the year plus a GRAMMY Award. You can hear why.

Whitley’s version:

“I Can Let Go Now” (Michael McDonald; 1997)

For any interpretive singer, the choice of material is key. And if the singer in question has Krauss’ range and chops and vision, some truly unlikely alchemy is possible. Among the best examples from the AKUS repertoire is “I Can Let Go Now,” a deep cut on Doobie Brothers frontman Michael McDonald’s 1982 solo album, If That’s What It Takes. Another amazing Krauss vocal in a career full of them.

McDonald’s version:

“Man of Constant Sorrow” (traditional; 2000-2002)

Before O Brother, Where Art Thou?, you wouldn’t have called singer-guitarist Dan Tyminski the unheralded “secret weapon” of AKUS. Nevertheless, he didn’t become a star in his own right until serving as movie star George Clooney’s singing voice in the Coen Brothers loopy, Odyssey-inspired farce. “Man of Constant Sorrow” was the hit in the movie and also on the radio, launching Tyminski to solo stardom.

Resonator guitarist Jerry Douglas especially shines on this version from 2002’s Live, recorded in Louisville – you can just tell everyone in the crowd was waiting for the “I bid farewell to old Kentucky” line so they could go nuts. Tyminski would have another unlikely hit in 2013, singing on Swedish deejay Avicii’s “Hey Brother.”

O Brother version:

“New Favorite” (Gillian Welch & David Rawlings; 2001)

Kraus sang on the GRAMMY-winning O Brother soundtrack, too, alongside Gillian Welch. It will come as no surprise that the Welch/Rawlings catalog has been a recurrent favorite song source for her. One of Krauss’ best Welch/Rawlings selections is “New Favorite,” title track of the thrice-GRAMMY-winning 2001 AKUS album. Though it’s edited out in this video, the album-closing version concluded with a rare in-the-studio instrumental flub, followed by sheepish laughter to end the record. Perhaps the AKUS crew is human after all?

“Borderline” (Sidney & Suzanne Cox; 2004)

The story goes that the first time Krauss was on the summer touring circuit, she’d go around knocking on camper doors at bluegrass festivals to ask whoever answered, “Are you the Cox Family?” Once she found them, she didn’t let go, and the Coxes became some of the best of her collaborators and song providers. Along with producing their albums, Krauss covered Cox compositions frequently; “Borderline” appeared on 2004’s Lonely Runs Both Ways, another triple GRAMMY winner.

“Big Log” (Robert Plant, Robbie Blunt, Jezz Woodroffe; 2004)

When Krauss first sang with Robert Plant at a Leadbelly tribute concert in November 2004, it seemed like the unlikeliest of pairings. But here’s proof that they had more in common than you’d expect, with Krauss covering a solo Plant hit from 1983. She sang “Big Log” on her brother Victor Krauss’ album, Far From Enough, which was released earlier in 2004.

This video pairs the Krauss siblings’ version with Plant’s original 1983 video, directed by Storm Thorgerson.

“Dimming of the Day” (Richard & Linda Thompson; 2011)

Fairport Convention guitarist Richard Thompson is one of the finest instrumentalists of his generation as well as a brilliant songwriter, especially with his former wife and collaborator Linda Thompson. This stately, bittersweet love song dates back to their 1975 duo LP, Pour Down Like Silver, and Linda sets the bar high with a stoic yet emotional vocal. Krauss more than lives up to it on the 2011 AKUS album Paper Airplane, which also offers another great showcase for resonator guitarist Douglas.

Richard & Linda’s version:

“Your Long Journey” (Doc & Rosa Lee Watson; 2007)

Krauss isn’t just a spectacular lead vocalist, but also an amazing harmony singer, one of the few who can hold a candle to Emmylou Harris. Retitled from the Doc/Rosa Lee Watson original, “Your Lone Journey,” this closing track to 2007’s grand-slam GRAMMY winner Raising Sand has Krauss’ most emotional vocal harmonies with Plant on either of their two albums together.

Doc Watson’s version:

“Heaven’s Bright Shore” (A. Kennedy; 1989, 2015)

All that, and she’s an incredible backup vocalist to boot. “Heaven’s Bright Shore” is a gospel song Krauss first recorded as a teenager on 1989’s Two Highways, her first album billed as Alison Krauss & Union Station (and also her first to receive a GRAMMY nomination). It’s great, but an even better version is this 2015 recording in which she’s backing up bluegrass patriarch Ralph Stanley alongside Judy Marshall.

AKUS version:

“The Captain’s Daughter” (Johnny Cash & Robert Lee Castleman; 2018)

The late great Johnny Cash left behind a lot of writings after he died in 2003, some of which were turned into songs for the 2018 tribute album, Forever Words: The Music. None of his songs ever had it so good as “The Captain’s Daughter.” This superlative AKUS version fits Cash’s words like a glove.

Continue exploring our Artist of the Month coverage of Alison Krauss & Union Station here.

Alison Krauss & Union Station figure prominently in David Menconi’s book, Oh, Didn’t They Ramble: Rounder Records and the Transformation of American Roots Music, published in 2023 by University of North Carolina Press and featuring a foreword by Robert Plant.

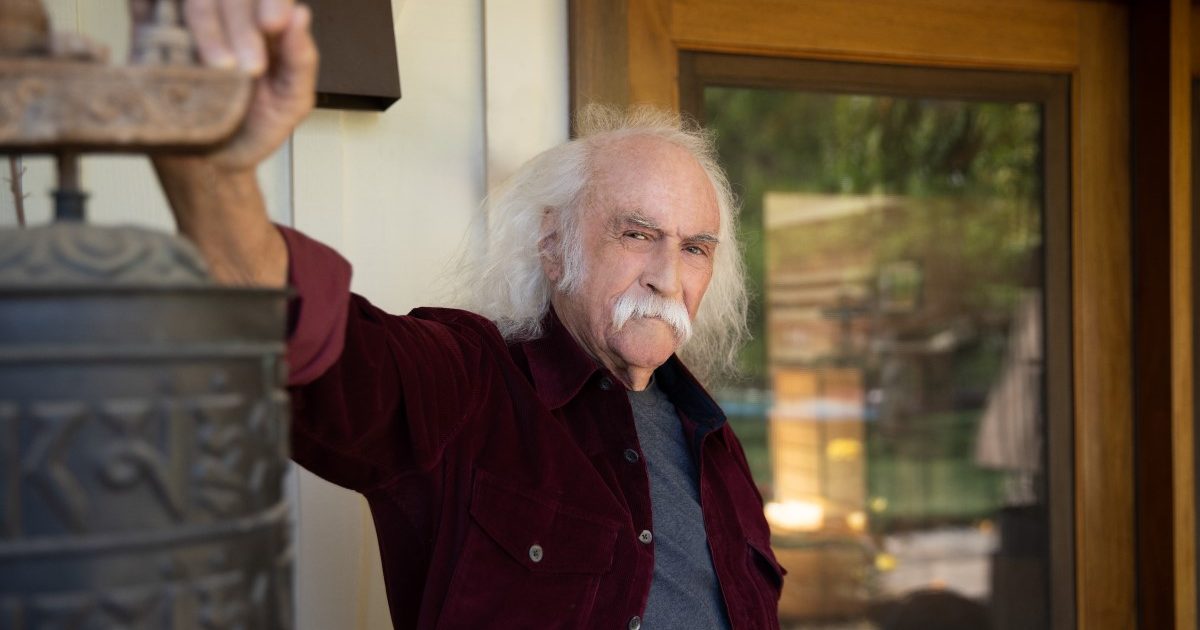

Photo Credit: Randee St. Nicholas