Depending on how much attention one pays to labels, singer-songwriter Robert Finley could accurately be called both a blues and soul vocalist, even though he’s also performed plenty of gospel, and has a passionate faith that is often reflected in comments about his unlikely emergence as a national figure in his 60s.

“You can’t call it anything except the hand of God a lot of what’s happened in my life,” Finley tells BGS. “For me to be recording and performing now, to have met and established a friendship with a young white guy like Dan (the Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach), and to be in the studio now recording and singing these songs when that’s what I’ve always wanted to do all my life, well it’s just God’s hand in my life.”

Robert Finley’s story is indeed a distinctive one. He was born in Winnsboro and raised in Bernice, Louisiana, and the lure of music was such he began playing the guitar at 11, purchasing one from a thrift store in town. “I remember hearing the gospel singers and people like James Brown,” he continues. “Singing is what I wanted to do from the time I was a kid, but as far as traveling and visiting places and doing some of what I’m doing now, no there’s no way I ever thought I’d be able to do that.”

One of eight children, Finley grew up in the Jim Crow South. His family were sharecroppers, and Finley was often working with his family in the fields picking cotton. When he got the chance, he attended a segregated school, but dropped out in the 10th grade to get a job. Now, at 67 years old, his voice has a power and authority that come from voicing experiences many only read about in history books.

The title of his third LP is definitive: Sharecropper’s Son, released in May on Easy Eye Sound. One of its singles, “Country Boy,” describes how Finley grew up. That’s working hard for little gain, carving out a life in less than desirable situations, yet never letting hardships or tough times overcome a burning desire to succeed. The video for the single was shot in the Louisiana fields where his family worked. The lyrics illuminate not only the backdrop of small town and rural segregation, but also highlight other places that have influenced and shaped his life.

Another important aspect of Finley’s life was his time in the service. His military tenure began in 1970, when he joined the Army to serve as a helicopter technician in Germany. But once more due to circumstances he again credits to divine intervention, the Army band needed a guitarist. He ended up accompanying the band throughout Europe until he was discharged, where he returned home to Louisiana. He initially split time between his other love, carpentry, and heading a spiritual group called Brother Finley and the Gospel Sisters. But then he was deemed legally blind and forced to retire as a carpenter.

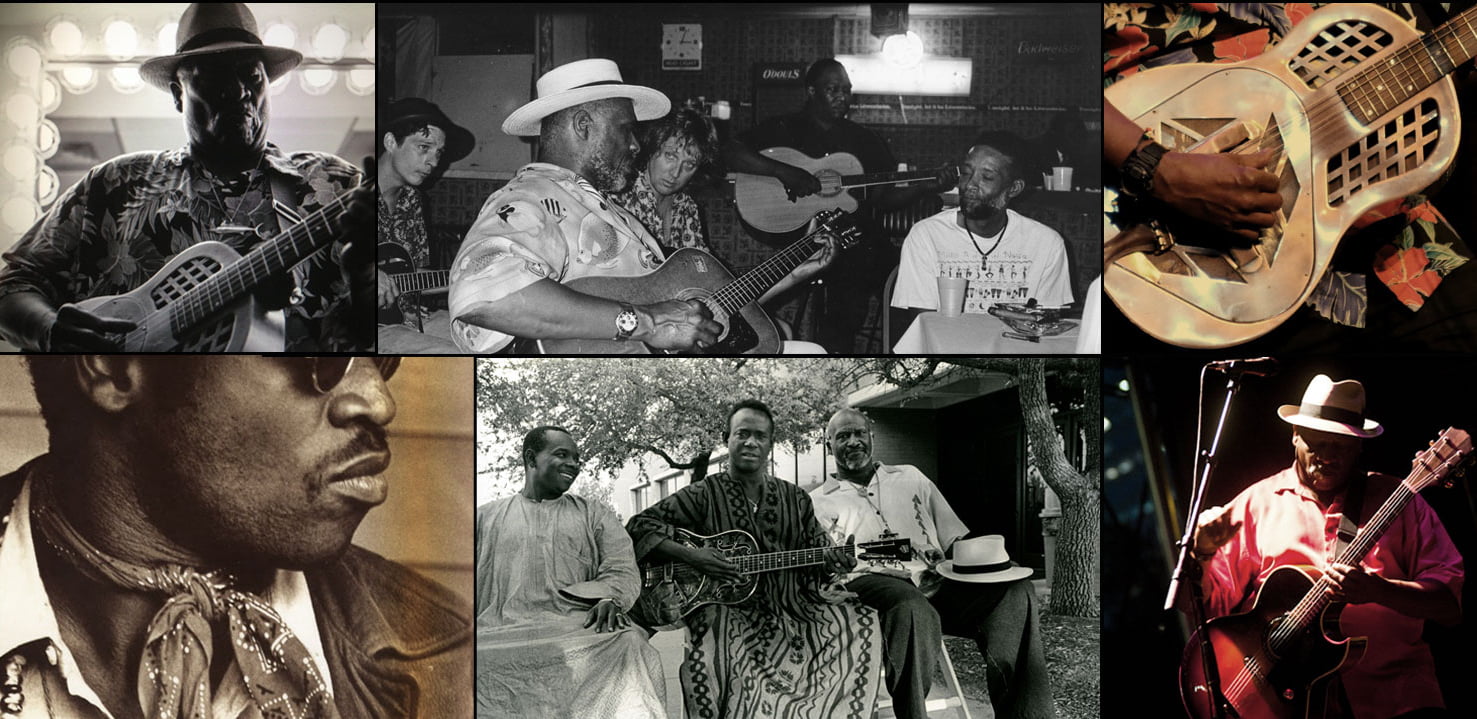

“Once again, I have to give credit where it’s due to God, because who knew that anyone had ever heard of me or what I was doing in Louisiana,” Finley says, marveling at the fact that the Music Maker Relief Foundation discovered him before a 2015 date in Arkansas. They were thrilled by his sound and helped start a new phase of his career, with Finley appearing on tours with such blues vocalists as Alabama Slim and Robert Lee Coleman. Subsequently the title track of his debut album Age Don’t Mean a Thing celebrated what was essentially an artistic rebirth, and that 2016 LP attracted widespread critical attention.

A big part of that was due to Finley’s raw, fresh delivery, one clearly steeped in the blend of spiritual and secular elements that comprise classic soul, yet vibrant, dynamic and contemporary rather than a retro reflection mimicking past greats. Finley wrote most of the material and was backed by members of the Bo-Keys. Shortly after the LP, he met Auerbach, forging a musical and personal kinship that remains strong to this day.

“To think I would meet someone like Dan, a young guy with the soul and skill of the old-timers,” Finley continues. “Man, I couldn’t believe it when I first heard him play, and when we started talking about music, how quickly we connected and we still do.” Their first project was an original soundtrack for the Z2 Comics’ graphic novel Murder Ballads. Later came Finley’s second LP, Goin’ Platinum, produced by Auerbach. Finley would also appear on Auerbach’s Easy Eye Sound Revue tour, and later do his own series of shows on a world tour.

Then came something Finley describes as a “dream happening.” He was a 2019 contestant on America’s Got Talent, though he was eliminated in the semi-final round. But before that his tune “Get It While You Can” was released in a sneak peek that generated even more interest, to the point Sharecropper’s Son has been eagerly anticipated.

Its lead single “Souled Out on You” depicts the end of a relationship and describes in vivid fashion the ups and downs that eventually caused what was initially seen as a great thing to end. But its essence is Finley’s life story, something he says “I was really ready to tell. Dan and the people he had in the studio were perfect for what I wanted to say. It’s almost like they knew it like I did, and it was really something sitting in that studio and being surrounded by that talent.”

The session’s musical excellence would be expected from a band of this caliber, with guitar assistance coming from Auerbach, Mississippi blues ace Kenny Brown and fellow Louisiana native Billy Sanford, as well as pedal steel player Russ Pahl. With Bobby Wood on keyboards, bassists Nick Movshon, Eric Deaton, and Dave Roe, legendary drummer Gene Chrisman, percussionist Sam Bacco and a full horn section on board, the various songs’ backgrounds, arrangements and solos are outstanding. Auerbach, Finley, Wood, and Pat McLaughlin shared compositional duties.

Given Finley’s history, it wouldn’t be unfair to think at some point there might be either some regret or bitterness expressed regarding events or personalities in his past. But nothing could be further from the reality. Robert Finley is one of the most upbeat, optimistic people you could ever hope to meet, and that resilience and formidable spirit can be heard in his singing, and is reaffirmed in the final things he says to end our interview.

“Yes, I still live in Bernice,” he concludes. “Why would I go anywhere else? I know these people and know this area. Both the places where I was born and grew up in now have Robert Finley Days and they gave me keys to the town. You really can’t beat that. I’ve lived long enough to be able to do what I love and make a good living. That’s the best of the many blessings I’ve gotten from the good Lord, along with meeting Dan and being able to tell the world my story.”

Photo credit: Alysse Gafkjen

Founded in 1974,

Founded in 1974,