Celebrating the rich history of women in old-time music, past, present, and future, has been an obsession of mine for over 50 years. I’ve listened to archival recordings, sat in the living room with Ola Belle Reed, Jean Ritchie, and Alice Gerrard, toured with Patsy Montana, taught Maybelle Carter’s unique guitar style, and interviewed Lily May Ledford at the Renfro Valley Barn Dance.

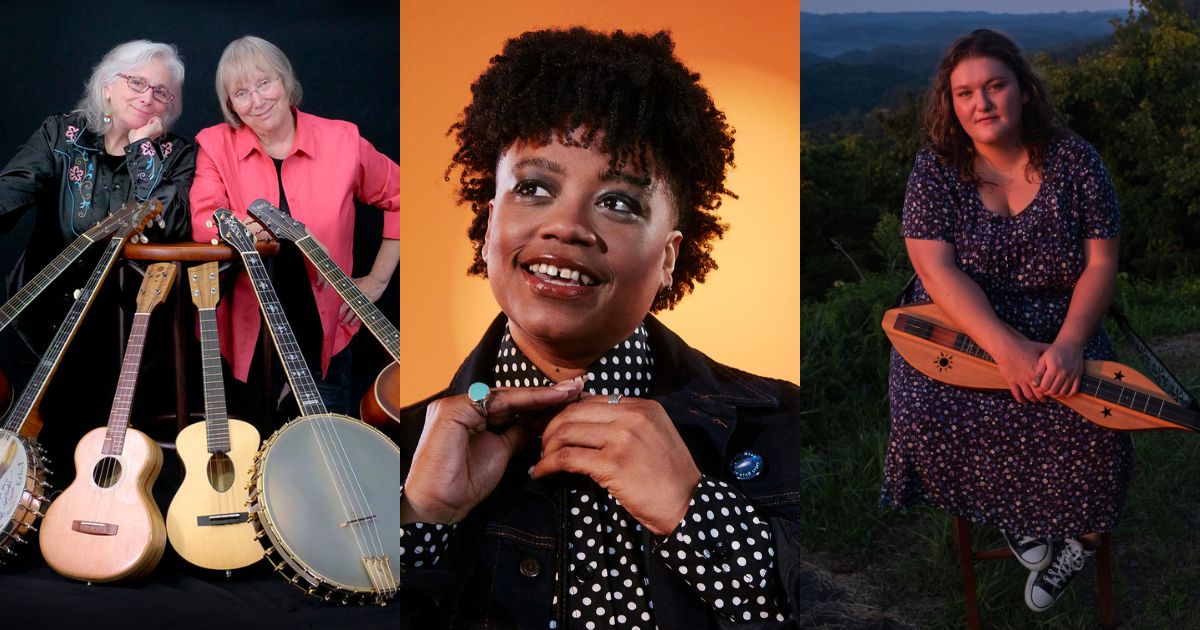

I was a proud member of the team that created The Birthplace of Country Music’s exhibit, “I’ve Endured: Women In Old Time Music.” And I’m thrilled that Baltimore’s Creative Alliance is hosting both the exhibit and the Say Sister! Festival celebrating women in roots music in January 2025. This playlist includes music from the past and the “I’ve Endured” exhibit, present artists from the Say Sister! Festival lineup – and the future is coming! – Cathy Fink, musician and co-curator

“I’ve Endured” – Ola Belle Reed

Ola Belle (1916-2002) was born Ola Wave Campbell in Grassy Creek, North Carolina. She was a fine traditional banjo picker and guitarist and grew up with a rich repertoire of family music. She also became a prolific songwriter, realizing that she had her own things to say and her own way to say them within the structure of old-time music. This song has been covered hundreds of times by contemporary artists. Ola Belle received a Distinguished Achievement Award from the International Bluegrass Music Association in 1998 and was awarded a prestigious National Heritage Fellowship Award in 1986.

“Polly Ann’s Hammer” – Our Native Daughters (Amythyst Kiah, Rhiannon Giddens, Leyla McCalla, Allison Russell)

A native of Tennessee, Amythyst Kiah performs both original and traditional songs on banjo and guitar. She dug deep into old-time music as a student at East Tennessee State University’s roots music program. In “Polly Ann’s Hammer,” the legendary John Henry takes a back seat and his wife gets the lead role. Like the “I’ve Endured” exhibit, this effort brings light to someone who has not received the attention she may have deserved.

“When John was sick/ Polly drove steel/ Like a man, Lord, like a man … This is the hammer that killed your daddy/ Throw it down and we’ll be free…”

“Things Are Coming My Way” – Marcy Marxer

Marcy adapted this song from the singing of Bessie Jones and the Georgia Sea Island Singers. Marcy met the Georgia Sea Island Singers during various folk festivals and always delighted in this song. She’s been celebrating the rich history of women in country music in our duo for over 40 years. Marcy’s a multi-instrumentalist on guitar, cello banjo, mandolin, ukulele, percussion and more. This song showcases her fingerpicking guitar style.

“West Virginia Coal Disaster” – Sarah Kate Morgan

Sarah Kate Morgan steps follow right after Jean Ritchie with traditional and original songs and dulcimer playing. She’s an innovative Appalachian dulcimer player with a gorgeous voice and a love for Appalachian music and heritage. Here she sings Jean’s potent song about the 1968 Saxsewell No. 8 Mine disaster. Hang in there for the awesome instrumental at the end!

Sarah Kate teaches at the Hindman Settlement School in Kentucky.

“Red Rocking Chair” – The Coon Creek Girls, Lily May Ledford

Lily May Ledford (1917-1985) from Powell, Kentucky played clawhammer banjo and fiddle and was the leader of the first all-girl string band on the radio, The Coon Creek Girls. Here her solo banjo playing is featured.

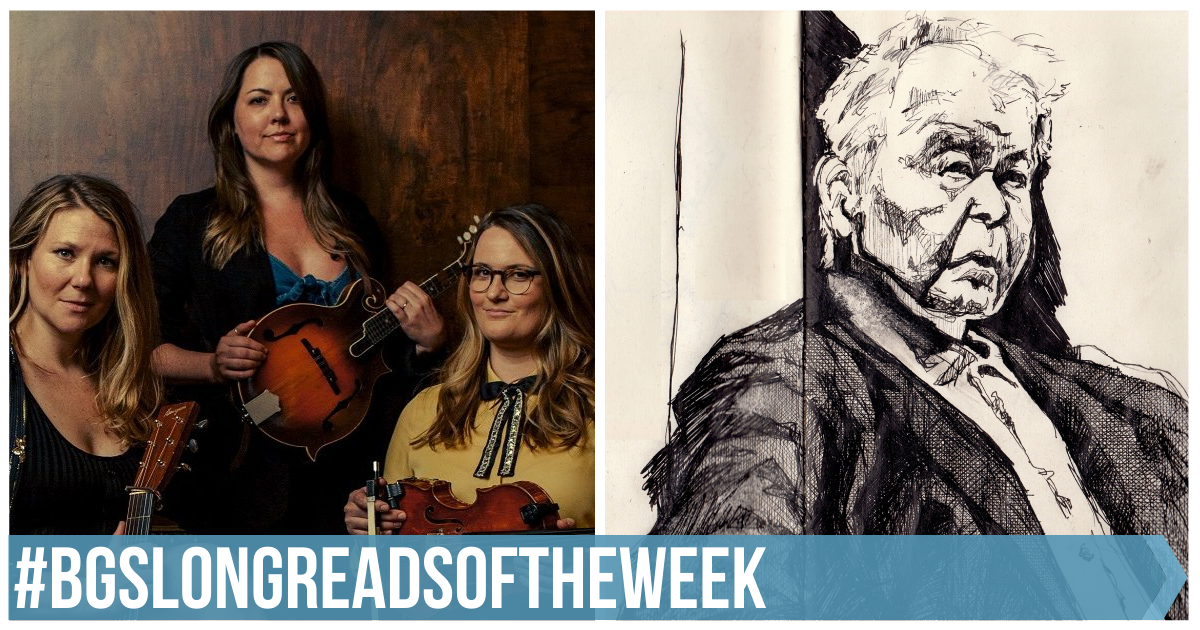

“Cotton Patch Rag” – Kimber Ludiker

Kimber plays fiddle and mandolin and sings with bluegrass group Della Mae. She’s a sixth-generation fiddler from Spokane, Washington. Here’s her winning performance of “Cotton Patch Rag” from the 2006 Grand Master Fiddle Championship.

“What The Lord Done Give You” – Cathy Fink

I was the first woman to win the West Virginia State Banjo contest (1980) – and went on to win it several times, total. In 2018 I also won the Clifftop Appalachian Music Festival Banjo Contest. This original song is played on a gut string fretless banjo, making a new tune sound old.

“I Will Not Go Down” – Amythyst Kiah featuring Billy Strings

From Amythyst’s most recent album, Still + Bright, comes this awesome collaboration with Billy Strings. It’s a powerful song and arrangement. I can tell you that if Ola Belle Reed were able to hear this song, she’d give it a big thumbs up! Speaking truth to power is part and parcel of women’s work in roots music.

“Muddy Creek” – Sarah Kate Morgan

Sarah Kate Morgan has redefined what can be done on an Appalachian dulcimer. Her trills, embellishments and awesome tone here are joined by fiddle, banjo and feet. This one will make you happy!

“Now Is the Cool of the Day” – Jean Ritchie

Jean’s clear soprano voice couldn’t be more beautiful than on this original song that draws on her traditional roots, while conjuring God’s calling to humans to take care of the earth. First released in 1977 and still timeless.

“No-See-Um Stomp” – Della Mae

Kimber tears up this original fiddle tune with an all-star band featuring Molly Tuttle, Alison Brown, Avril Smith, and Della Mae.

“Chilly Winds” – Cathy Fink & Marcy Marxer

Cello banjo (Marcy) and five-string banjo (Cathy) make up the instrumental duo behind the vocal duet in this classic old-time song.

“The Little Devils” – Jean Ritchie

Jean’s solo voice reminds us what it must have been like to gather round the fire after dinner and hear her mother sing to the family before the age of television.

“Banjo Pickin’ Girl” – The Coon Creek Girls, Lily May Ledford

This song has become the unofficial theme song of many a banjo pickin’ girl and string band. Lily May Ledford and the Coon Creek Girls sang this on the WLS Barn Dance (Chicago), Renfro Valley Barn Dance (KY) and Lily May continued singing it solo for the rest of her career.

Say Sister! Festival takes place in Baltimore, Maryland at the Creative Alliance on January 10 & 11, 2025. Tickets – in person and “watch from home” – are available here. The “I’ve Endured: Women of Old Time Music” exhibit opens at Creative Alliance on January 3 at 6pm.

Photo Credit: Cathy Fink & Marcy Marxer by Irene Young; Amythyst Kiah by Photography by Kevin & King; Sarah Kate Morgan by Jared Hamilton.

Poster Credit: Gina Dilg