When the Wailin’ Jennys got back in the studio to record their new album, Fifteen, which celebrates the group’s anniversary together, Nicky Mehta, Ruth Moody, and Heather Masse didn’t have much time. Five days, to be exact. Between the fact that all three women are mothers now and live in different cities, planning and preparation have given over to spontaneity and trust. But their approach on this latest LP — a set of covers — doesn’t sacrifice any of the considerate care that has always infused their siren-song harmonies. If anything, they’ve used the studio to capture the magic they radiate during their live shows.

There’s a confidence brimming from every song, whether it’s their reverent, respectful, or resplendent

takes on Dolly Parton’s “Light of a Clear Blue Morning,” Emmylou Harris’s “Boulder to Birmingham,” and Tom Petty’s “Wildflower,” respectively. The trio seems poised and ready to create original music at some point — schedules permitting — but in the meantime, they’ve jumped back into the waters, and are enjoying the stirring act of raising their voices at a time when the messages they’ve come to deliver need sharing more than ever.

What it is about this creative relationship that keeps bringing you all back together?

Nicky Mehta: It’s sort of never been discussed that we would ever take a break and not keep working together. I think it’s always been assumed that we would continue on as long as it felt satisfying to all of us. I think this is a type of project that none of us have access to outside of what we’re doing, so it’s a unique thing for all of us to be doing. That’s what keeps us coming back. We also have such an amazing audience that are really faithful and have seen us through a lot of hiatuses, and I think we want to come back to them, as well.

Heather Masse: I think people have been as receptive. I feel like the live shows, people are there with you and fully present and still really excited about it.

Ruth Moody: I agree. I think we’ve been so lucky with our fanbase. We have taken three hiatuses. Each time it was for each of us to have babies, procreate. [Laughs] And each time our agent was like, “It’s too long to be off the road,” and every time we came back, our audiences have been there and continued to grow over the last 10 years — 15, but specifically 10 since Heather joined the band. Who knows why, but we have been lucky in that way.

As you ebb and flow from this project, how do you see yourself fitting within the growing number of female trios in North America? There are many more names on that list now, beyond folk even.

NM: I think that’s something that I’ve observed, as well. It’s crazy how many trios are out there now, which is great, and everybody’s doing something different. What they focus on, in terms of style of music, is different. We’ve always made decisions about breaks in the road from a place that’s really necessary for each of us, personally. I don’t think we’ve ever worried too much about that because there are things we have to do and so we’ll see what happens after. Once you’ve taken one break and things successfully resume, there’s less trepidation about that. It sort of feels as though there are a lot of trios out there, but it hasn’t felt like there’s some huge competition.

Your harmonies have a touch of the familial about them, and yet you’re not related by blood. How do you explain that magic?

RM: We’ve been really lucky with our blend. We all grew up singing and singing harmonies, and so it’s something we do instinctively — blending with other voices — so that helps to have the ability to listen and blend. But even then it’s not always a slam dunk, so I think we’ve been really lucky that our voices do blend and the ranges are compatible. We switch around depending on who’s singing lead, but we’ve been lucky that that’s been the natural fit.

HM: When I first met the ladies, they were playing in Philadelphia at World Café, and I was sort of auditioning, and the only place that we could sing was in a handicapped women’s bathroom that we found. I was astonished when we all started singing together that it felt like I was singing with my sisters. We just got lucky. It is like we’re sisters, so it’s nice.

I can’t even imagine what the echo would’ve sounded like in that bathroom!

HM: It was really special. I think it was a particularly flattering echo.

You covered Dolly Parton’s “Light of a Clear Blue Morning” for the Canadian film The Year Dolly Parton Was My Mom some years back. Her version has a praise and worship style about it, but yours feels more hymnal. How did you strike upon that interpretation?

RM: That was a good example of being pushed a little bit to do something. The director of the film really wanted us to do that song because the whole soundtrack is Dolly Parton. She wanted us to do it and she wanted it to be a cappella. Who knows if we would’ve gravitated in that direction, but that was cool that we got those instructions, and it really set our focus in that way. I think the best way of making something effective — if you’re going to do a cover — is to approach it in a different way. Especially in the beginning, before it gets into the groove, it does have a more plaintive, hymnal feeling. I think that did make it different from the original.

You triple the vocals on the line “Everything’s gonna be alright,” before going back into harmonies. To me, as a female listener, it feels so necessary to hear that from other women, especially with everything going on these days. What kind of message do you hope to be offering still?

NM: I think we all share the wish to heal and comfort people with what we do, and I think that we all do our own thing, in terms of staying on top of what’s going on in the world and addressing it in different ways. But in terms of what the band does is to reach out to people and support and have the music give people relief and hope and the feeling like, eventually, things will be okay. A lot of our audience, they work in fields where they’re addressing a lot of these issues all the time, and I think it’s nice for them to be able to come to a concert and feel that there’s understanding and there’s still love out there and there’s still hope.

The Tom Petty cover feels apt, although I realize you recorded before his passing. Why “Wildflowers,” in particular, besides the fact that it’s a great song?

HM: I think there’s a way in which, when we hear a song or we bring a song to the band, we sort of know if it’s going to be a Jennys song or not, if it’ll work with our configuration and the way we arrange things. I can’t remember if I brought it up — it felt like something that was on all of our lists of songs to cover — I know that, in my mind, I always thought of it as being a great Jennys cover. It’s hard to describe what the qualifications would be for a Jennys song, but it has a lot of openness and the message is really beautiful, and the melody is very beautiful.

RM: A lot of tenderness, too. It leads itself so well to harmony, which is always a factor for us.

True, you wouldn’t want to pursue a song that doesn’t give you that space.

RM: Yeah, exactly.

It’s a beautiful rendition. So I know recording this album happened quickly because of your differing schedules, but oddly enough, it feels like one of your most grounded albums. What contributed to that sense of confidence?

HM: We only had five days, but we have years of being together and working together that kind of went into it. Even though we knew it would be a bit frantic with a lot of challenges, we knew that we had the foundation. This album was, essentially, for the fans, because they have waited so long for a new record, and so, in spite of not having a lot of time and being mothers, we wanted to make this happen. We thought an appropriate way to approach the album would be to do it live off the floor, and to do a more pared-down recording that mirrors our live performances. That probably helped us feel comfortable and confident in the studio because we’re doing what we, essentially, do on stage.

RM: I think becoming a mother, also, you just have such a different perspective on everything. We didn’t have a lot of time, and normally I feel we can get a little up tight and be perfectionists about stuff. And we were able to let some of that go a little. It’s the perfect album for feeling more grounded and more natural, because we didn’t have time to go back and redo things or try new things out. We just kinda did it and had to be okay with whatever happened, because we didn’t have the time to do anything else. Sometimes there’s a real magic to that.

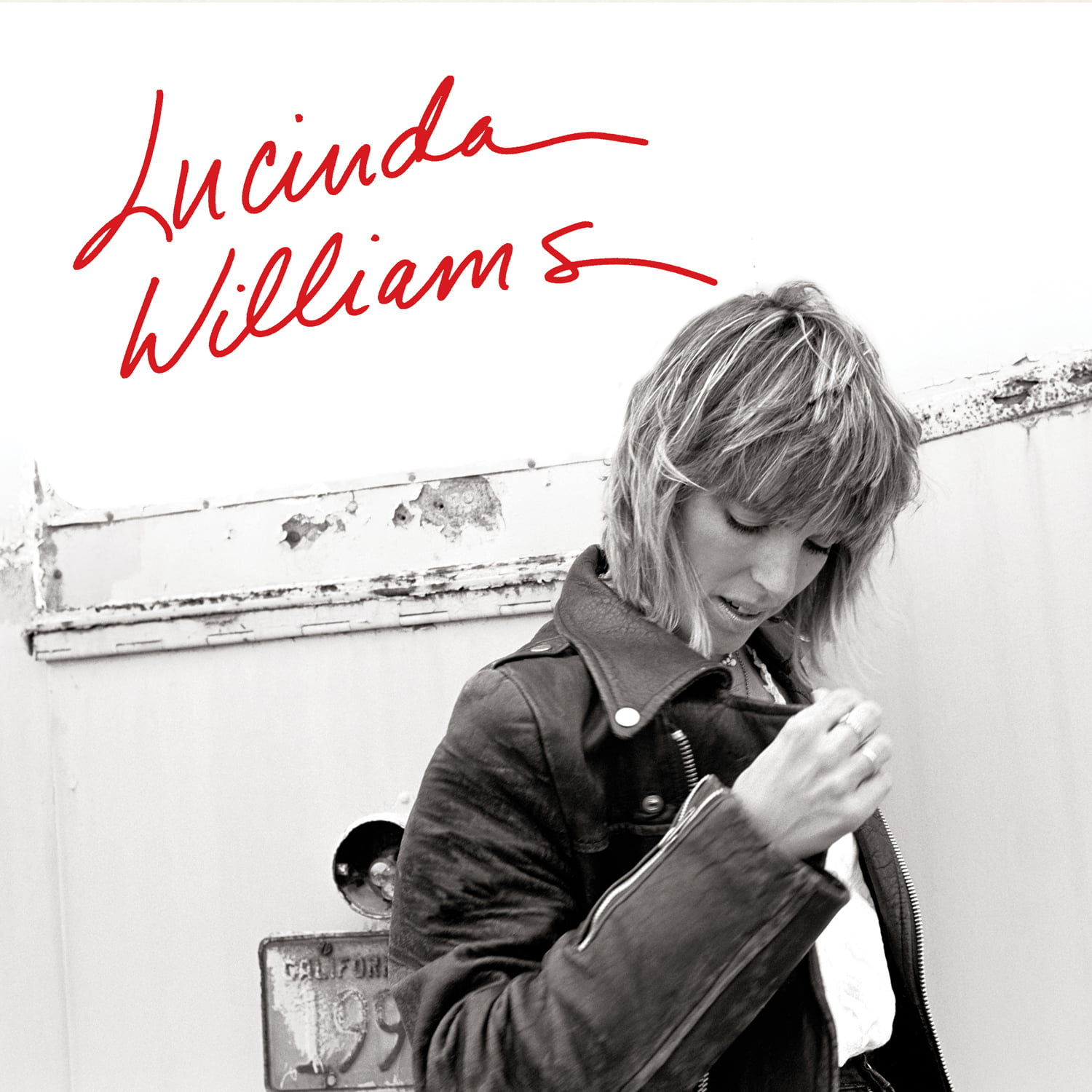

Photo credit: Art Turner