Welcome to the BGS Radio Hour! Since 2017, this weekly radio show and podcast has been a recap of all the great music, new and old, featured on the digital pages of BGS. This week, we bring you new music from John Hiatt and Jerry Douglas, Yola, and more from our Artist of the Month, Chris Thile! Remember to check back every week for a new episode of the BGS Radio Hour.

Bill and the Belles – “Happy Again (I’ll Never Be)”

To kick things off on the Radio Hour this week is a new release from Johnson City, Tennessee-based Bill and the Belles. We caught up with them recently on our 5+5 series, where they discussed hosting the revived Farm & Fun Time series in Bristol, Virginia, as well as their musical influences and career-based mission statements. Between lead singer Kris’ songs, their great harmonies, and instrumental prowess, Bill and the Belles are just plain enjoyable.

Sam Filiatreau – “Wrecking Ball”

When asked about his musical influences on a recent 5+5, Louisville-based Sam Filiatreau highlighted country greats John Prine and Guy Clark. Those influences combined with his classic twang shine through on “Wrecking Ball.”

Loose Cattle hope they’ve made Porter & Dolly, Johnny & June, and John Doe & Exene all equally proud with this track, written by their longtime friend and songwriter Paul Sanchez.

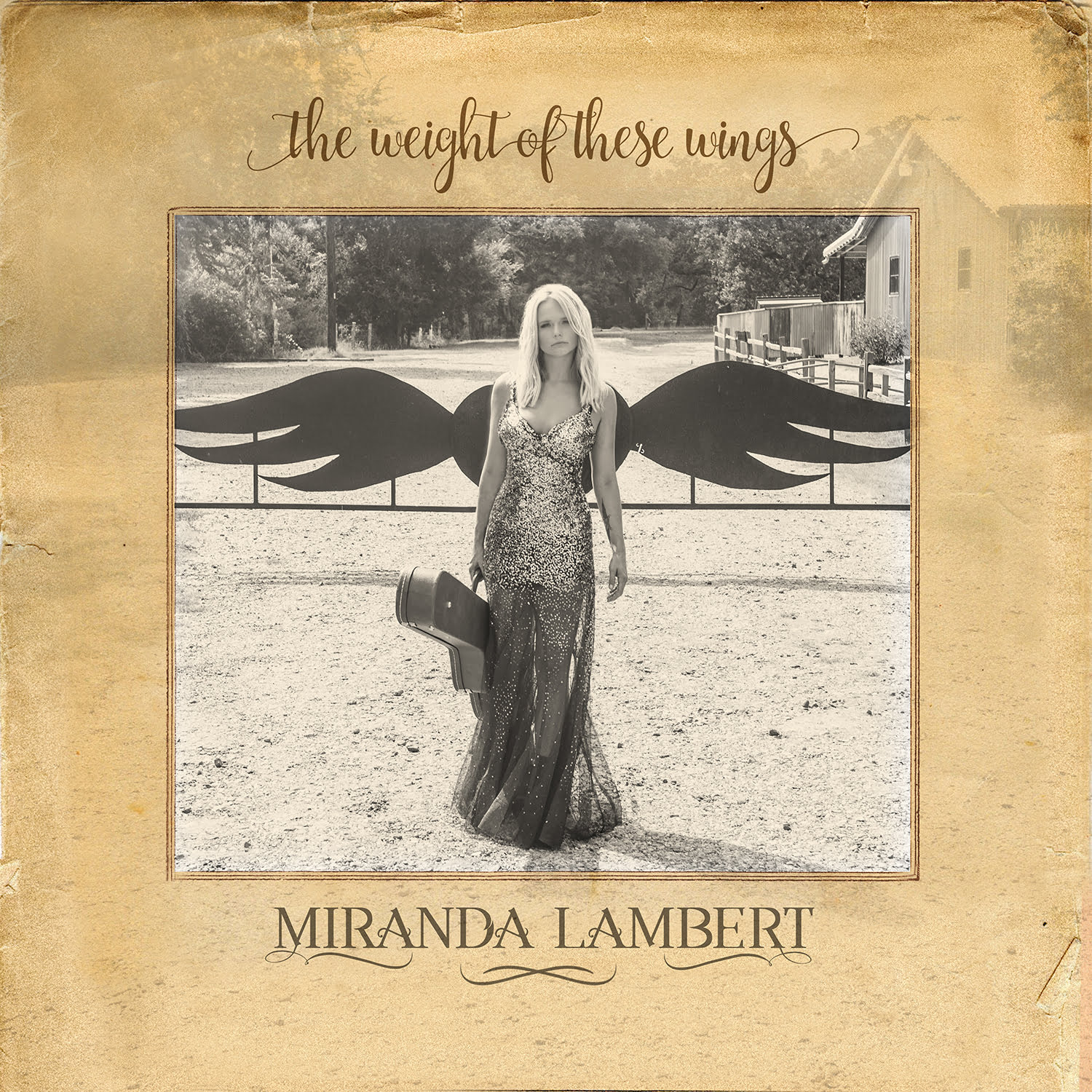

In this new live version of “Tin Man,” Miranda Lambert reminds us how moving a simple performance can be. The solo acoustic version of the track comes from a new album and film that Lambert and fellow songwriters (and proud Texas natives) Jack Ingram and Jon Randall have crafted. Titled The Marfa Tapes, the album features the recordings that are shown in The Marfa Tapes Film.

Our Artist of the Month, Chris Thile, has been the busiest man in bluegrass for a long time. Between hosting Live From Here, shows with the Punch Brothers, or Nickel Creek reunions, Chris didn’t get to slow down much before the pandemic forced him to. Recorded in an old church-turned-studio, his new album Laysongs reflects on his Christian upbringing and community, and how that relates to where he is now.

In the words of Turner Cody and the Soldiers of Love, “Lonely Days in Hollywood” is a “kind of meditation on the transactional nature of our culture of celebrity; how our dreams belie reality and nothing is for free.”

Tray Wellington originally wrote the main riff for “Pond Mountain Breakaway” on the electric guitar, but then realized it would be well-suited for an uptempo bluegrass tune.

For his latest record, famed roots singer and songwriter John Hiatt enlisted the help of the Jerry Douglas Band. Recorded in famed RCA Studio B in Nashville, Leftover Feelings returned Hiatt to his earliest days in town when he lived in a $15-a-week rented room on Music Row. Although the space could easily intimidate due to the amount of classics recorded there, Hiatt suggested that you don’t actually think about it, because it’s such a comfortable environment.

Paula Cole’s new album American Quilt showcases her impressive vocal range as she sings some of her favorite American standards. She chose “What a Wonderful World” to close the album intentionally, stating that the song “unifies people.”

We caught up with Drew McManus of Satsang recently, and he shared with us the touching story of “Malachi,” a song about his son, which he wrote in the hospital the night he was born.

“O Death” is the latest installment in Rhiannon Giddens ongoing collaborations with her partner, Francesco Turrisi, a gifted Italian multi-instrumentalist. Their new record, They’re Calling Me Home, was inspired by the year they spent together in Ireland, amidst the pandemic. They’re Calling Me Home echoes the many ways that a tumultuous 2020 had many of us yearning for the comforts of home, of the past, or of those that were called home from this world.

“Stand For Myself” is Yola’s newest single from her upcoming album, set to release in July. The track is a mix of “symphonic soul and classic pop,” and its message is universal — that real change can come from thinking, living, and standing for ourselves.

Tim Raybon & Daniel Grindstaff of Merle Monroe hope listeners will be captured by the classic sound and wonderful story line of “Shelby Tell Me.” In talking to BGS recently, they stated, “our intention is to move the listener emotionally through the lyrics and melody.”

When BGS spoke with Beau Roberson of Pilgrim about “Darkness of the Bar,” he shared that the song “…is about the dark struggles of life, and trying to see the light in those dark times.”

Photos: (L to R) Miranda Lambert by Jim and Ilde Cook of CookHouseMedia; Yola by Joseph Ross Smith; John Hiatt by David McClister