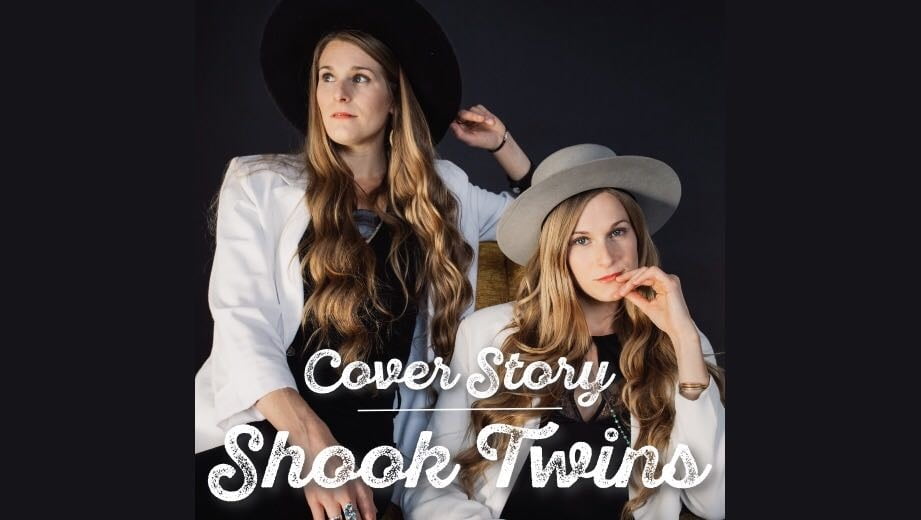

Shook Twins — the duo composed of sisters Laurie and Katelyn Shook — have abided by the label “quirky” ever since they released their first album, You Can Have the Rest, in 2008. Their process of integrating unexpected sounds, looping, and multiple instruments (including a golden egg typically used for percussive flares) may seem unconventional, but those touches serve as thoughtful embellishments to elevate their honeyed voices.

On their new album, Some Good Lives, the Portland, Oregon-based musicians put those voices to use in praise of good men. At a time when women’s narratives have increasingly come to the fore, Shook Twins instead focus on the positive influence certain men have had on their lives. The choice suggests there’s room to strike a balance, rather than cast one gender aside to uplift another.

Following in the footsteps of their archivist grandmother, Some Good Lives is an amalgamation five years in the making — a blend of original songs and “found sound,” of a sort. Katelyn spoke to the Bluegrass Situation about the band’s new project.

BGS: Your grandfather played piano — you even include a clip of it on the album. So it seems like you have music in your blood.

Katelyn Shook: Yeah, that was our first musical experience. We’d go over to their house and lie under his grand piano. He was totally untrained, just [flying by] the seat of his pants. That’s why I had to put those snippets on there, because it’s so Grandpa. We started singing really young and fell in love with it. We chose to be in choir but we didn’t pick up instruments until we were 17.

“Grandpa Piano” and “Moonlight Sonata” aren’t really “found sound” pieces, but they provide an interesting texture to the tracks that you wrote. What was the thinking behind including those?

I wanted to sprinkle those in because it goes with the theme of Some Good Lives. I realized that a lot of the songs were about somebody or dedicated to somebody, and all of them happened to be men, which blew my mind. I was resistant to it at first, like, “Now is not the age of man!” I just wanted to honor women. But then I had to realize and keep in check that there’s a balance, and we need to remember and honor the good men in everybody’s lives.

We’d grown up with such good men, and that’s what made my life so balanced. Most of them have passed away, except for two, so I sprinkled in “Grandpa Piano” because there was not really a song dedicated to my grandpa, but he was such a big musical influence on us.

Considering that so many people want to make room for new stories, how have you made the case that now is a time to also share stories about men, even if they’re positive?

I don’t know. I don’t know that I’ve made that case. We’ve always lived by example, and talking with all the women around me, I honestly feel like Laurie and I are very rare in our generation to have such positive male impacts in our lives. It’s funny when a theme pops up. It’s not like we went into this record like, “We want to honor the good men.” It just came out.

On “Dog Beach,” which was originally written by your grandfather Ted, you added your harmonies to an old recording. How did you retain that original, almost old-timey sound quality?

That song is a trip! It’s a long story, but I’ll try to keep it short. My grandma was an archivist, and she had this tape recorder always going. Anytime we had a campfire with our family, we made [Ted] play that song, and he was always resistant to it because he never thought it was a great song. But it was the only one he ever wrote. Ted passed away in 2015 from this massive, traumatic heart attack out of the blue. It was terrifying, horrible. After he passed away, my dad was listening through those tapes, and we heard “Dog Beach” on there. We didn’t even know it’d been recorded — Laurie and I were 5 at the time.

I heard that, and I got the idea to sing this with him one last time. We were in Portland, and we had a whole bunch of friends over— including his ex-wife and his daughter, who’s our best friend — and I had the tape with me and a shitty tape player. I put it in to play it, and we’d sing along and record it. I hit play and it ate the tape. I was like, “No!” But I knew it wasn’t the only copy — we had another one at home — so I called my boyfriend, woke him up (because he was staying with my parents), and I made him go inside with my dad and look for this extra tape. They found the other tape, they found a tape player, put it in there, and it ate the tape.

It sounds like at this point Ted didn’t want you to share it.

Exactly, but I knew he was just fucking with us because he was always resistant to playing it at campfires. So they took the tape out and they put it together — it didn’t break, it just unwound. Then my boyfriend went to sit in the car, which was the only other tape player we had at the house. If you go back and listen to his recording, you can hear his puffy coat rustling. He’s in the car just voice memoing it on his iPhone, and then he emails me the voice memo, and we play the voice memo in the living room. This all took an hour. It’s emailed through time and space. I don’t know, it’s the way it worked out. It was such a crazy night.

What was the recording process like? I know it took a few years to get to that place after your last album, but it seems like it was worth that wait.

This process was a lot different. We normally block 20 days, and we go to the studio and knock it all out. But this time we took our sweet-ass time. We did it in several chunks. We’d been playing these songs live, and we might choose not to do that with our next album, but I really like to because it lets the song marinate. We recorded three songs first and then we’d listen back to them, and since we’d been playing them live, we added more stuff to it. It was a cool way to do it but it took forever.

I think “Vessels” might be one of my favorites on the new album, both for the message and for the vocals.

That one is really special to us, too. It’s dedicated to one of the men who’s still alive, but he has a brain tumor. We wrote it right after we found out he had it.

Is he around your age?

He’s four years older, but he’s super healthy and super young. It’s super nuts. When we wrote it, we were still in that phase where he could die at any moment. It’s a really gnarly brain tumor. Nobody survives this. It’s a total miracle that he’s come this far — it’s been like five years now. But we were in this state of shock and terror, we had our moments of coming to grips with it. That song was us accepting that we’re just vessels, and we have to say goodbye sometimes, and we have to be thankful that we got you at all. It’s narrow, singing to him, but it’s a broad statement to everybody about accepting your death, your friend’s death, and finding a way to be ok with it.

Vocally, we really like what Laurie did. That’s another song that Gregory Alan Isakov helped out on. She took four songs to him. She repeats lines, talking; I really like that effect because it made it this ghostly statement. Isakov helped make it sound more vibey; we call it adding “God noise,” where he adds all this weird ass-shit, and he tweaks it in Pro Tools, but the stuff he comes up with, he’s a total genius. His essence, his God noise, made that song extra special for sure.

Familial harmonies have their own kind of magic, but as twins you have similar vocal cords, which seems like it could pose a challenge at times. What kind of thought process have you put into your arrangements?

We use that vocal identicalness to our advantage. We’ve started to experiment with more unison singing. It’s trippy because people try to achieve that in the studio, where they double themselves, and you can’t really tell there’s two tracks, but there’s an essence. That’s what it sounds like. Harmony-wise, it’s mostly Laurie; it just comes out of her. When we analyze it, sometimes we’ll totally overlap and all of a sudden one voice will naturally go lower and one will go higher. We don’t do the typical harmony. We intertwine. It’s very trippy.

As twins, how have you managed to forge a sense of individuality in the duo?

It sounds weird, but it’s never been an issue to express ourselves individually. We’ve always been Shook Twins. We actually strive to be more of a duo. Sometimes we play solo and it doesn’t feel right; we don’t enjoy it as much. I think we’re definitely strongest together. We’ve never had a competition issue. We always say, “We’re the twin-iest twins we know.” Most times we meet other twins and they all have their own lives. It’s kind of weird to us. We’ve always had the exact mindset about everything. It’s crazy.