As we turn the page on another year, the Bluegrass Situation has compiled ten music-related books from 2018 that may appeal to fans of bluegrass, roots, classic country, and yes, even alt-country.

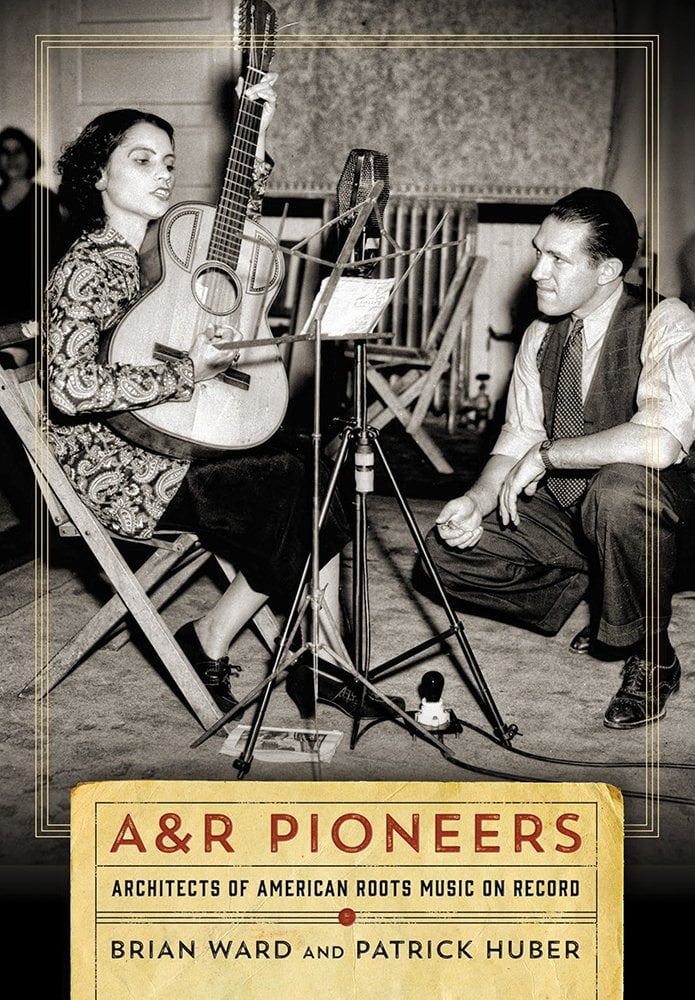

A&R Pioneers: Architects of American Roots Music on Record

Authors: Brian Ward and Patrick Huber

Some musicians just have that “it” factor – as true 100 years ago as it is today. This historical volume looks at the men and women who shaped raw talent for record labels as A&R (“artists and repertoire”) scouts. With an emphasis on roots music, the book focuses on important figures like Ralph Peer, Art Satherley, Frank Walker and John Hammond, as well as many less-celebrated figures. It also acknowledges that some of these A&R executives were not exactly virtuous. Authored by two professors, the project is jointly published by Vanderbilt University Press and the Country Music Foundation Press.

Bill Monroe: The Life and Music of the Blue Grass Man

Author: Tom Ewing

In addition to spending 10 years on the road as Bill Monroe’s bandleader and guitarist, author Tom Ewing may be the foremost expert on the Father of Bluegrass. At 656 pages, this biography ties together Monroe’s personal and professional life without glossing over the tougher times. Ewing writes with the knowledgeable bluegrass fan in mind, making this an especially rewarding book for students of bluegrass and those who are familiar with Monroe’s contemporaries. With hundreds of new interviews and rare access to Monroe’s archive, Ewing is able to build a comprehensive narrative that is likely to become the definitive account of an American music legend.

The Blue Sky Boys

Author: Dick Spottswood

Born and raised in North Carolina, the Blue Sky Boys emerged as one of the first and finest brother duos in country music. As teenagers, Bill and Earl Bolick riveted radio listeners in the Southeast with a stunning harmony blend. Earl sang baritone lead and acoustic guitar, while Bill sang tenor vocal and played mandolin, although their music was never fast and high like bluegrass. A deal with RCA Records in 1936 led to appealingly understated recordings such as “The Sunny Side of Life.” Drawing on archived interviews and Bill’s written accounts, this biography also compiles vintage photos and a complete discography.

Bluegrass Generation: A Memoir

Author: Neil V. Rosenberg

Author and historian Neil V. Rosenberg vividly recounts his own experiences with Bill Monroe and many other memorable characters at the Brown County Jamboree and the Bean Blossom Bluegrass Festival in the early 1960s. Through these recollections, Rosenberg shows how these seminal concert events helped solidify Bill Monroe as a bluegrass icon. Rosenberg’s scholarly reputation is already well-established, thanks to his prior books and the title of Professor Emeritus of Folklore at Memorial University of Newfoundland. Yet this volume is more personal, as it describes how an eager college student in Indiana became entrenched in bluegrass banjo and the festival scene.

Buffy Sainte-Marie: The Authorized Biography

Author: Andrea Warner

In February, Buffy Sainte-Marie will receive the People’s Voice award at Folk Alliance International in Montreal. Presented to an individual who unabashedly embraces social and political commentary in their creative work and public careers, the songwriter known for the poignant 1964 anti-war anthem “Universal Soldier” fits that description neatly. This approved biography portrays the Cree musician as an advocate for Indigenous rights, as well as a woman who endured a traumatic childhood and intimate partner violence. Feminist author Andrea Warner distilled more than sixty hours of original interviews into an insightful story that illuminates Sainte-Marie’s activism and art.

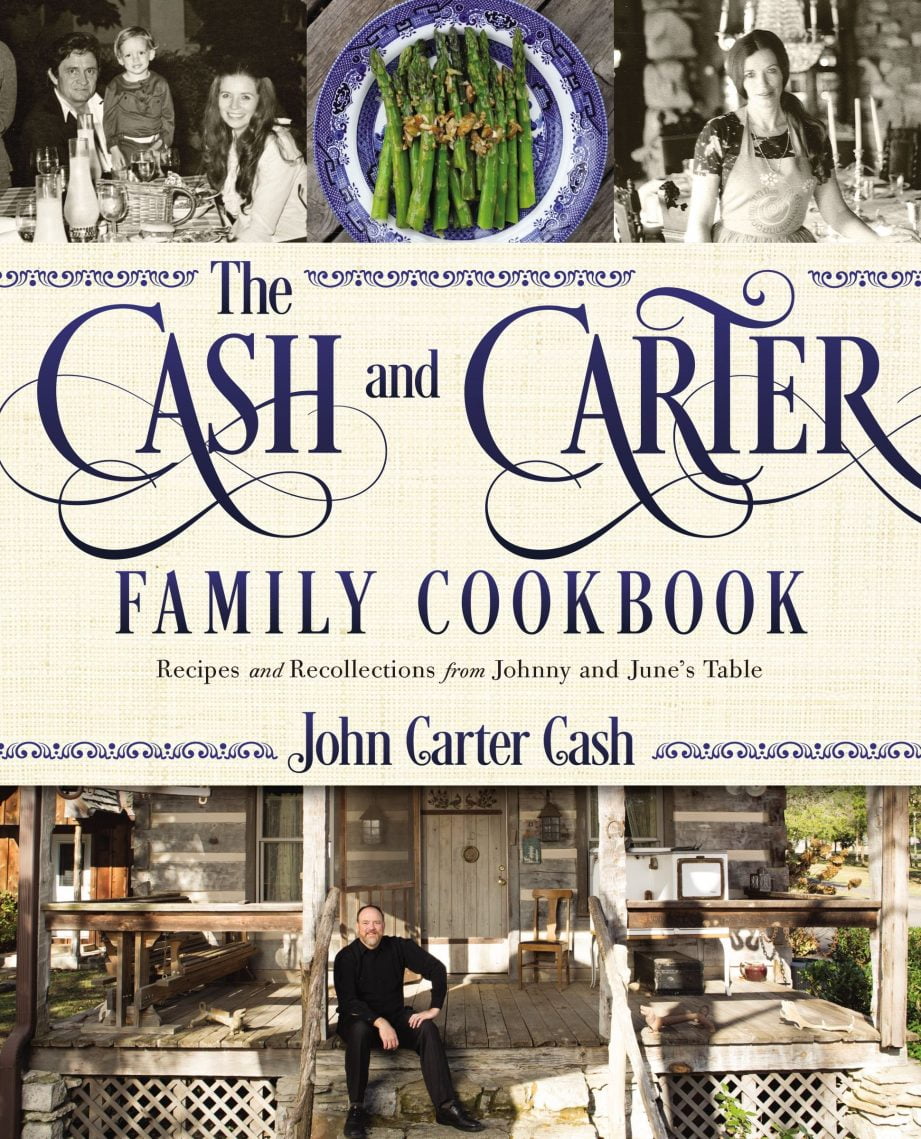

The Cash and Carter Family Cookbook: Recipes and Recollections from Johnny and June’s Table

Author: John Carter Cash

John Carter Cash is a foodie and it shows in this lovely cookbook dedicated to his parents, Johnny Cash and June Carter Cash. Family recipes abound, with the first two recipes being June’s biscuits and Mother Maybelle Carter’s tomato gravy. This isn’t all Southern cooking, however. Johnny and June also liked Asian flavors and vegetarian dishes, including their own veggie burger (a.k.a. Cashburger). The full-color photos are beautiful but the coolest pic is in the front, where the Man in Black presides over a barbecue wearing a white apron and shorts. His famous recipe for Iron-Pot Chili is in here, too.

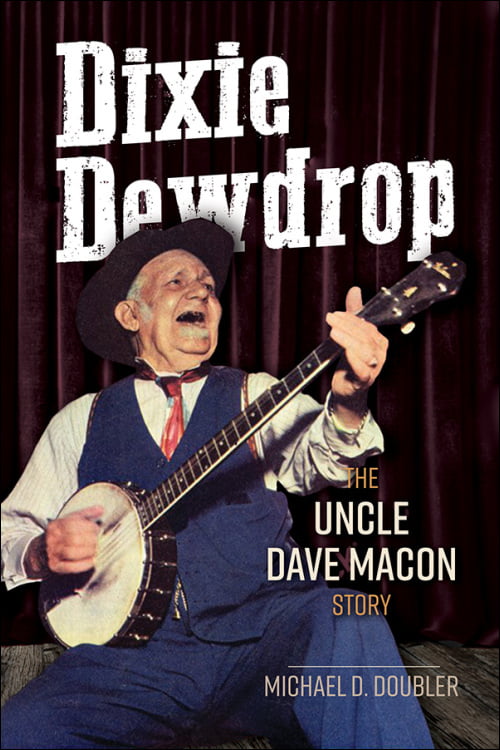

Dixie Dewdrop: The Uncle Dave Macon Story

Author: Michael D. Dubler

Considered the first superstar of the Grand Ole Opry, Uncle Dave Macon is remembered as one of the finest banjo players of his era. This well-researched biography by his great-grandson, Michael D. Dubler, also captures the entertainer’s complex personality. Pulling from original and archived interviews, the narrative provides a detailed account of Macon’s recording output, as well as crucial personal moments, such as his father’s murder in Nashville. Because Macon’s career didn’t really take off until he was 50, the book also conveys just how much strength – both physical and emotional – it took for Macon to stick with it.

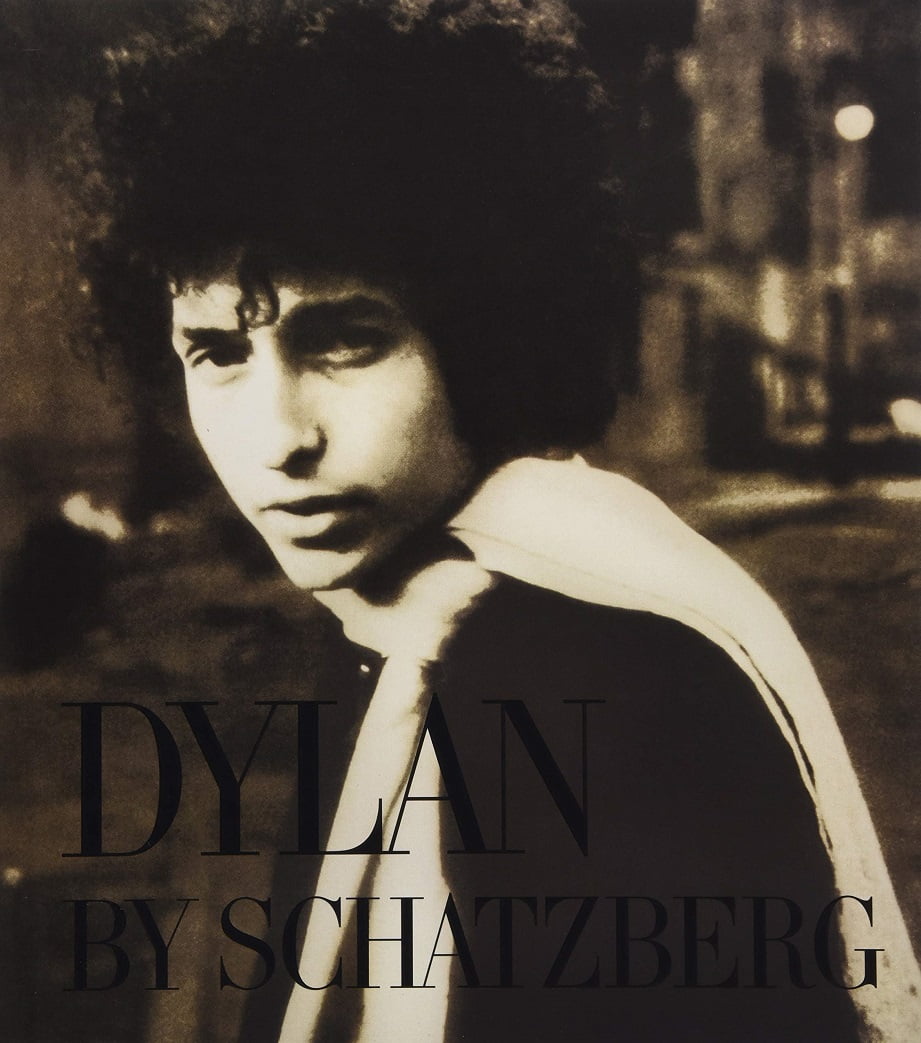

Dylan by Schatzberg

Author: Jerry Schatzberg

Bob Dylan seems the epitome of cool when gazing at the lens of photographer Jerry Schatzberg, who took innumerable pictures of him in the 1960s. Now in his 90s, Schatzberg has compiled personal stories and never-before-seen photos from that era for Dylan by Schatzberg. Inside, the enigmatic subject is documented in recording studios, concert stages, and city streets. For example, Schatzberg snapped the famously blurry Blonde on Blonde album cover in the Meatpacking District in Manhattan. Some believed it was a metaphor for drug use, but Schatzberg says it’s out of focus simply because both men were shaking in the cold.

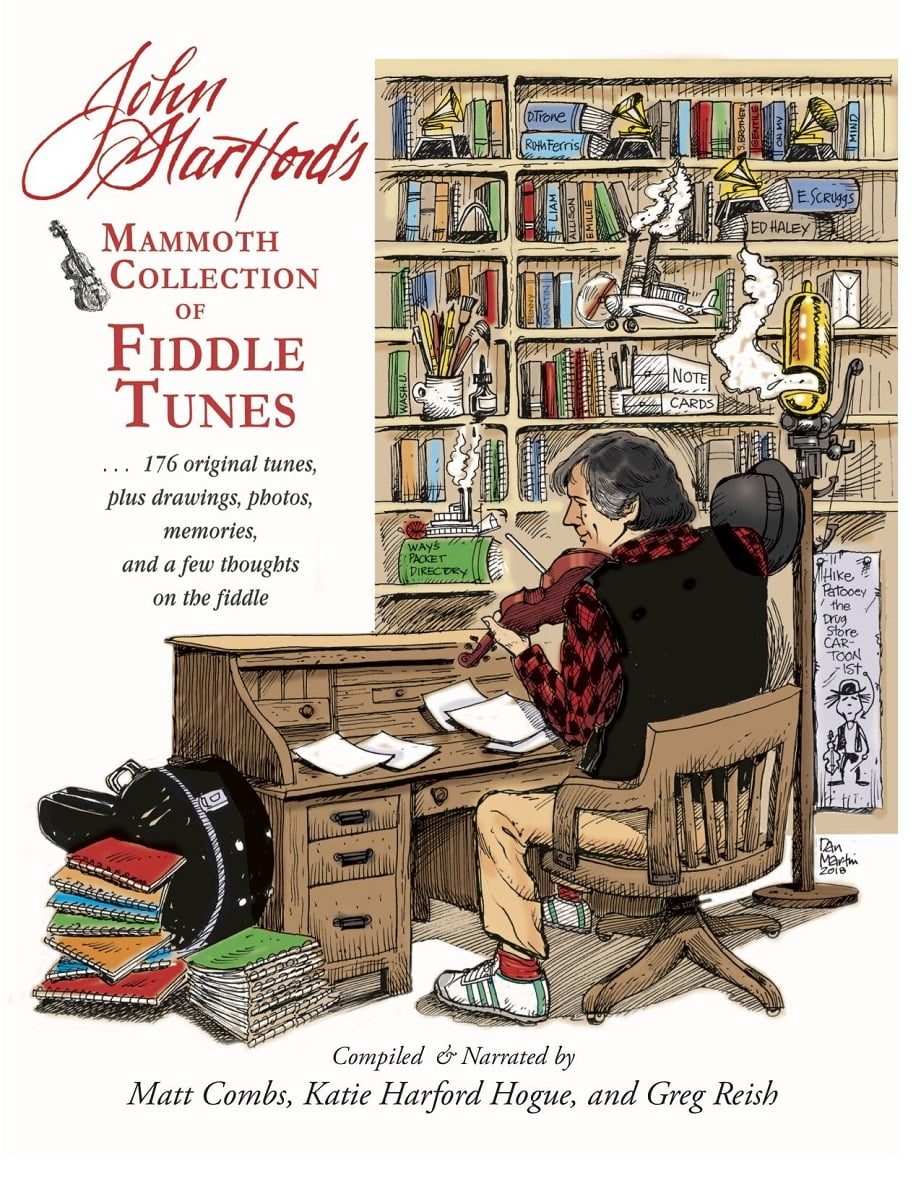

John Hartford’s Mammoth Collection of Fiddle Tunes

Authors: Matt Combs; Katie Hartford Hogue; Greg Reish (Author), John Hartford (Illustrator)

One of acoustic music’s most treasured talents, John Hartford left behind a brilliant legacy that is ceaselessly resonant. This full-color book goes a long way to explain why generations of bluegrass fans continue to admire him. Co-authored by accomplished fiddler Matt Combs, Hartford’s daughter Katie Hartford Hogue, and musicologist Greg Reish, the volume expands beyond career landmarks like writing “Gentle on My Mind” and recording Aereo-Plane. Readers can also peruse 176 original compositions (some never before published), more than sixty of Hartford’s personal drawings, interviews with musicians who still consider him an essential player of American music, and Hartford’s own ruminations on playing the fiddle.

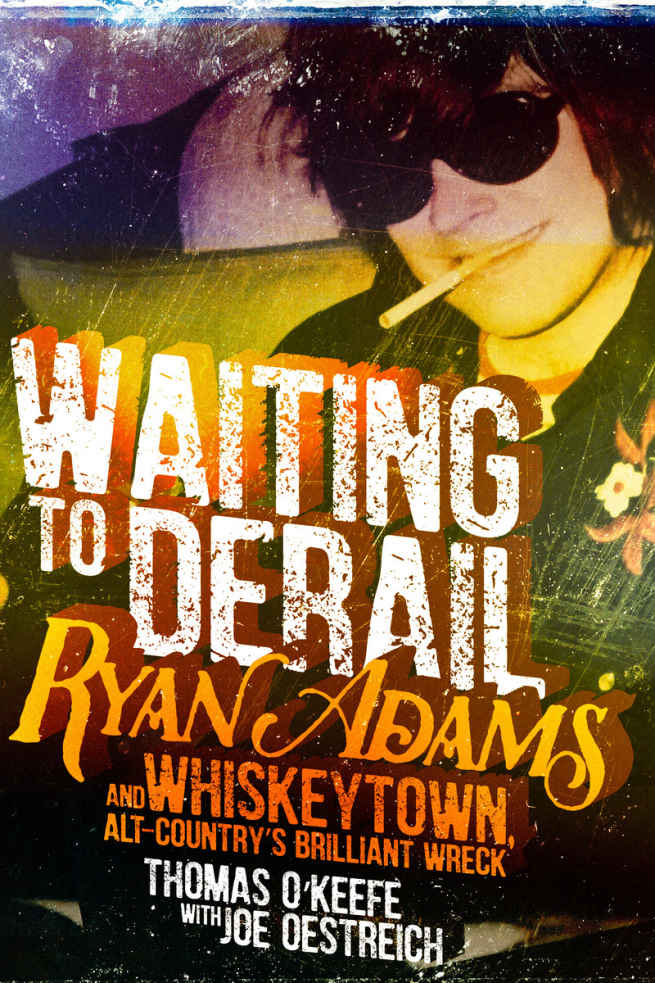

Waiting to Derail: Ryan Adams and Whiskeytown, Alt-Country’s Brilliant Wreck

Author: Thomas O’Keefe

Time has been kind to Whiskeytown’s 1997 album, Strangers Almanac, with country-tinged tracks like “16 Days” and “Yesterday’s News” paving the way for the Americana movement. (Back then it was usually called “alt-country.”) But why didn’t the band have more national success? This candid book written by their former tour manager makes it obvious that Ryan Adams didn’t care about playing nice to fans, venue owners, influential radio programmers or the music industry. Still, there’s an important scene where Adams silences a North Carolina club with “Avenues,” serving as a potent reminder of just how powerful his music can be.