Colin Linden is a musician’s musician, a player who pretty much does it all. At 11, he was hanging with Howlin’ Wolf. At 13, he was learning to fingerpick at the knee of David Wilcox. By the time he was in his mid-20s, he was working with members of the Band. Having recorded several albums as a solo artist and with his band — Blackie and the Rodeo Kings — played myriad sessions for T Bone Burnett, and produced albums for the likes of Lindi Ortega and Bruce Cockburn, Linden has a lot to say about making records, for himself and with others.

You came up playing the blues. You’ve been a sideman for everyone from Robert Plant to John Oates. You’ve made your own records, you’ve made records with the Rodeo Kings. Where on that spectrum did you decide it would be a good idea to become a producer?

Well, I always loved making records. From the very beginning — in addition to being somebody up there singing and playing guitar and picking up songs — I always dreamed about making records. I always found that records were fascinating, even from the labels. When I was a little kid, it was kind of a parlor trick that I would blab off all the credits from the records. You know, like, “Mother’s Little Helper” was three minutes and 49 seconds; it was on London; it was produced by Andrew Loog Oldham … all that. That was kind of a parlor trick for my brothers to parade around when I was five.

You too, huh? [Laughs]

Records were always a really big deal for me. There was a magic in it. I didn’t live in a place, as a little kid, where there were people sitting around playing guitars or sitting around the piano singing songs or any of that. Our world was records.

And, not that there’s anything wrong with the way that we listen to music today, but there was a certain aesthetic in the way that you listened to recordings in those days. You went to the stereo in the living room or your bedroom and you sat next to it. You had that piece of artwork and all that information in your hands. It was an entirely different world than it is today.

It was absolutely a glorious experience to put on a record, to listen to a song you loved, and to be able to put it on again and listen to it over and over. It was an absolutely glorious experience. It was the key to another world that you knew existed out there somewhere. It was absolutely real. In some ways, it felt like it was more real than your own life. For me, records were really a big part of it. So I always wanted to make records.

In terms of actually thinking about producing records, I kind of evolved into doing it because I loved being in the studio so much. I began to get calls from friends of mine in the blues scene, especially in Toronto. They would say, "Man, every time I go into the studio, the engineer makes me turn my amp down and turn my reverb off and it’s rotten. But when you come in with me, you always seem to have a good time when you go in." That’s how it started. There were a few people early on who were really encouraging to me and who I got to work with in some cases.

The first guy who ever recorded me in a professional environment was Daniel Lanois. He had already moved out of his mom’s basement, which was where he and his brother had started their studio. They bought a house in Hamilton called Grant Avenue and, when I was 18, I had my first experience as a session player. I loved working with Dan. I loved his whole aesthetic. There was something about it — it was not a clinical approach, even though it was before Dan had started doing a lot of the things that he later mined in terms of recording in unique environments. It was something that I could really relate to, and it made me feel very comfortable and excited about the process.

There’s a certain similarity to your producing approaches, at least to my ears. Is that accurate? Does he have some influence on the way you approach things?

Absolutely! I love his music. I love his production and I love what he does. I’m real good friends with T Bone Burnett — for over 24 years now. He’s my mentor. Every time I get to play on a record for him, it’s like I get a lesson in production. There’s so much that I learned from him. And I love him as an artist, too. I think so many of the artists who’ve had an influence on me, especially in the last 20 years, have been people who come about it from a record-making point of view — be it Willie Dixon or Allen Toussaint or Cowboy Jack Clement. And then, of course, T Bone and Dan. I think they’re real masters.

You just name dropped three of the best there are! [Laughs]

Yeah, I think so, and I think that they’re great artists, as performers, as well — all of them, all of the ones I just mentioned. You can add more — Johnny Otis, Smokey Robinson — these guys understand music from in front of it, from behind, from the sides, from above, from below. There’s an element that you get, I think, when you work with people in a production capacity, or even a collaborative capacity of any kind, that allows you to have a different viewpoint of how a song works and how a piece of music works.

Smokey’s an interesting one to bring up. Can you talk specifically about him as he relates to your music? That’s interesting to me.

For me, he always reached down and got some real truth as a songwriter from the simplest ways of saying something. I think, on the records that he produced for Motown, there was a certain kind of timeless soul. Especially in the mid-'60s period. All of those guys — Holland/Dozier/Holland, Berry Gordy — all of them. But there was something about Smokey that seemed to touch a more soulful nerve for me.

The most recent record on your resumé other than your own is Lindi Ortega’s Faded Gloryville. That’s an interesting record. Three different producers, three distinct sounds. Tell me about your part in that.

For me, I didn’t really think, "Okay, what am I doing differently than the other guys that are going to be on it?" … although I enjoyed the idea. I thought it was kind of a nice, modern template to have one guy do a few songs and another guy do a few songs. I have a great deal of respect and affection for Dave Cobb’s work. I don’t know him that well, but he seems like a fantastic guy. I really like him a lot. Same with John Paul White. I’ve only played with him a couple times, but we get along really well. So I kind of felt like we had something different to offer, but we all kind of enjoyed some of the same food groups. So I was really pleased that we all got to work on the record that way.

So much of my approach with Lindi is connected to guitar playing. I know that she likes certain types of sounds. So I get on guitar and she is encouraging and gives me free rein to come up with guitar tones and approaches, and that I can kind of just be her guitar player. That’s where some of it starts. She goes for real simple approaches. She doesn’t want to make something too quirky, or too unnecessarily complex, which is something that I can relate to. When she gets behind a microphone, she stands and delivers, too. I produced an album for her a couple years ago called Cigarettes & Truckstops, and I really enjoyed working with her. We hit it off really well personally. We did that record very quickly, like we did these tracks quickly. It was like, "Okay, let’s go make a record. Let’s go out and make a record." It wasn’t like we had meetings about other meetings, leading us to other meetings and then, in six months, try out all the ideas and maybe have a meeting about it. It was very straightforward. We were going to go in and make a record. We were going to work with three different producers and these were the songs we wanted to work on. Let’s do it!

There’s a certain thread between you guys that makes the record come off really well.

I’m glad that you feel that. It really felt like that for me, too. I actually had never intentionally done a project like that. But now I’m encouraging other artists to take that approach. These days, the nature of making albums is different than it was — just the way people are getting songs. I still think the world is a better place for thinking of a body of music that lasts for 40 minutes instead of three or four minutes. I think that listening to somebody’s music that comes from a certain period of time, and has a cumulative effect, is a really powerful thing. I believe in the medium of an album of one sort or another. But I do really like the idea that some people can help paint a bigger picture by looking at a smaller amount of work. I really enjoyed the experience of doing that.

You’ve been doing this long enough that you must have a few cool, fun, weird, unusual stories. You can change the names to protect the innocent, but have you got anything? [Laughs]

Well, it’s a little easier for me to say, "Hey, what was this record like?" And then I can remember it. The things that are unpleasant are really weird. I try to forget, and I’m actually becoming better at doing that. From somebody saying, "You better turn up the piano or I’m going to stop liking this song and I’ll make sure it doesn’t come out" … it’s like, don’t shoot yourself in the foot!

Let’s talk, then, about the process of your new record Rich in Love. What was the process from start to finish? Did you have 10 or 12 meetings with yourself about that?

It’s such a funny thing with that record because it was grown right here in our house. Basically, it’s the result of the deep friendship and personal relationship that both my wife and I have with John Dymond and Gary Craig. Gary has been playing drums with me for 31 years and Johnny’s been playing bass with me for 25. Those guys are my closest friends. For 18 of those years, we played with the greatest musician any of us have played with: Richard Bell. The record is such a reflection of our relationship together — it’s a real co-production.

We did the majority of the recording right here in the house. We did one day at House of Blues, which was very nice. Gary Bell let us come in to do some reconnaissance recording and I didn’t even know if it was going to be on the record, until the record was 85 percent finished. There were songs that I didn’t know were going to make the final cut but they did, and really made the record better, I think.

We spent one day at Sound Emporium B here in Nashville, a place I love to work at, to do some overdubs. Charlie Musselwhite’s stuff was recorded at the studio in Clarksville and Amy Helm’s stuff was recorded at Levon’s studio. Aside from that, everything we did, we did right here at the house. I was working on the Nashville TV show and I had a shoot.

So, Johnny and Gary came to the house and we said, "Let’s do some recording." The worst that could happen was we’d see where the songs were at. The most that would happen was maybe some of what we do will end up being on the record. So, I was working on the Nashville show and I had a shoot to go to. I came back from the shoot four hours later, and my wife, Janice Powers — who wrote three of the songs on the record with me — and Johnny had put up a bunch of curtains in the studio and they had moved the couch out and Gary had set up his drums there. They had taken the couch cushions and placed them in wildly precarious and very interesting and unexpected positions. So I came back to the house, and the studio was completely changed. And it sounded great! That’s really how it started. We kept it that way and, in between the food and the wine, we ended up getting a lot of work done. We did that in a few different blocks. They would come down every couple weeks and we would just chip away at it. The record is such a reflection of our relationship with them.

I would say, then, that your relationship with them — if I were to base it on hearing that record — is a very lush, elegant, and thoughtful relationship.

Well, good! I’d be honored, if that’s the case. I think that "lush" might be thought of in more than one usage of the word.

[Laughs] Well, you did mention wine!

We did drink a lot of wine in the making of the record.

“Knob & Tube” is one of my favorites from your record. I love the lyrics, I love the turn of phrase, I love the groove.

I’m so glad. That one was really grown right at the kitchen table. I had the title for it. The song was built so much like the rest of the record was built: There was a ukulele on the kitchen table. One of the things I do is impersonate an 11-year-old girl playing the ukulele.

There are two little girls who are unbelievably talented, also from Canada: Lennon and Maisy Stella, who play ukulele on the show. On the recordings, I usually end up playing the ukulele and she will end up learning the parts. So, I had the ukulele on the kitchen table because I had to go give her a lesson or something like that. I gave Janice the title of the song. Gary, I think, was working on another session, but Johnny, Janice, and I were at the house. And I said, "We should write a song with this title" and, 45 minutes later, she came down with bunch of lyrics to the first verse or two. We all started chipping in, throwing in lines, and I had the ukulele here. Immediately, I picked it up and the motif of the music came up. So it was really written right around our kitchen table, and we recorded it within 24 hours of when we wrote it. It was grown the way the record was grown.

Gary came back to the house and we set up a mic in the kitchen. It was a little too boomy for it to be good in the kitchen, so we went back in the studio, which was about six feet away. We recorded the song and, 45 minutes later, it was exactly what you hear. We added Amy [Helm] to it and a second piece of percussion. There’s sort of a subliminal electric guitar that I added, just using the room in the back, to give it some rumble. Aside from that, what you hear is exactly how we played it.

That’s why I enjoy these interviews so much. I love hearing about how things happen and the process behind it. Tell me about the process for “Luck of a Fool.” Was there a particular artist or record that influenced the sound of that song? It has that kind of reverb-drenched cowboy thing going on.

You know, it’s funny. I didn’t really even think of it that way, so much. I guess I had a few of the lyrics ready for it. I think I wrote that one in the middle of the night when I was having insomnia in Fredericton, New Brunswick. I was stranded there in a snowstorm after Blackie had played there and I couldn’t get back to Nashville for another day. I sat down and that idea just came to me. For me, it wasn’t so much of a cowboy thing as it was a gospel music thing. I always loved it when, before the bridge or chorus of a song, you moved up an inversion. Even if the chords didn’t change that much, just if the melody moved up. That was something I really liked, and something I was thinking of regarding that song. We did the actual recording of it here in the little room. It sounded good with more of the mics open, it sounded like it was bigger. I wasn’t sure exactly how we should take it, in terms of producing it. When we had Reese Wynans on it, Reese said, "Man, I think it’s cool as shit that you don’t have anything else but guitar, bass, and drums. I can play a tiny little organ part and that will be it." I thought, "You know what? Reese is a pretty smart guy. Let’s do that."

It’s cool when you’re in that kind of setting, and there’s the respect of great musicians, beautiful ideas come out of it. It’s really quite brilliant.

I think that’s just the nature of it. When you’re working with people that you’re already friendly with, it’s easier for that to happen. But I have to say, you get more and more confidence in that being the way it is when you work with somebody like T Bone. T Bone is so incredibly supportive of people’s ideas and of letting people be who they are. He makes you feel, when you’re on a session, that even if there’s someone better than you, you’re the one who he wanted to be in the room with him on that day. That kind of confidence, that whatever your contribution is and whatever is inherent about who you are, is what you’ve got to bring to it. It’s not that he’s haphazard about it either. He’s the kind of guy who will let something get to a certain point, and he’ll be sitting in the back of the room, encouraging its development. Then he’ll move up to the desk and start playing with things. Then, 30 seconds later, everything will sound different and better. He’s absolutely brilliant that way. He lets it develop by having confidence in the strength and having faith in the character of the people that he’s chosen to be there. It always serves the spirit of the music. I think that’s what he holds in the highest regard.

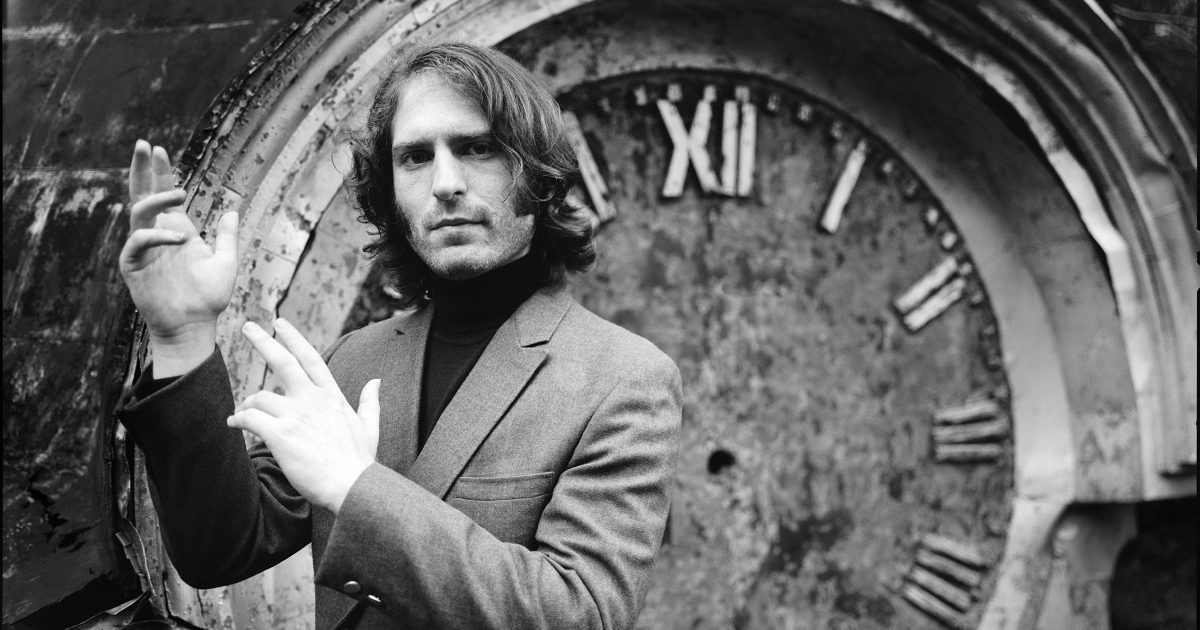

Photo by Laura Godwin