Holding the attention of a roomful of moderately smashed bar-goers is no small feat, let alone with a traditional Irish folksong. But last May, country singer-songwriter Dylan Earl ended his set at Brooklyn’s Skinny Dennis standing on top of the bar and singing an a cappella version of “Wild Mountain Thyme.”

“Will you go, lassie go/ And we’ll all go together/ To pull wild mountain thyme/ All around the blooming heather,” Earl implored in his warm baritone, towering above the room in worn jeans, boots, and a sleeves-cut-off T-shirt from his Arkansas-based label, Gar Hole Records. In spite of all the alcohol collectively consumed by the listeners who packed the venue to its beer-tinged walls that evening, the room was just about as quiet as a divey honky-tonk can be.

By ending his set with the kind of folk song which, passed down through generations, comprises one major lineage of country music – indeed, “Wild Mountain Thyme” is based in a much older Scottish folk song – Earl invoked a deep vernacular tradition and history often left out of modern country. Earl’s music attracts labels like “old-school” and “classic country,” and his voice certainly lends itself to those comparisons, but his own compositions convey a whole lot more. Rejecting the banality of tired Southern stereotypes, Earl writes punk-hearted, poetic music rooted in a love of people and place; music which is both socially and class-conscious and captures wide-ranging cultural unease and indignation with nuance and wit.

On his fourth studio album, Level-Headed Even Smile (released September 19), Earl makes clear that his is not a return to a bygone era so much as a carrying on of a long tradition of speaking truth to power and of imbuing dimension and worth into the lives of overlooked characters and issues too easily reduced to absolutes.

“I’d rather be an outlaw than in with the law/ All this authority worship is the strangest thing I ever saw,” he sings in “Outlaw Country,” a thesis statement of sorts for the album and Earl himself. Earl wrote “Outlaw Country” out of frustration at how many people made assumptions about his beliefs and morals because of his appearance – and because he plays country music with a whole lot of Southern twang. Earl wanted to make it clear where he stands.

“I finished high school in a very rural part of Arkansas; I identify with the Deep South, but I don’t identify with its most prevalent fucking right-wing rhetoric… I still want to remain approachable to those people I completely disagree with, because I think that’s an important part of making art, is creating discourse,” he says. “I want to try to approach these people and try to have that conversation. Be like, ‘Listen here, brother, I’m just like you, but you don’t have to be a racist piece of shit. It’s way more fun in life to be happy and be inclusive. Your soul will be happier because of that.’”

Lately, outlaw country morphed from its subversive roots into a shorthand for wicked good independent country or a slightly more specific alternative to Americana. While both wicked good and independent, Earl’s version also rekindles contempt for the establishment that fueled the original outlaw country movement:

I’d rather be a bootlegger than a bootlicker

A side stepper than a homewrecker

And I don’t get a pick me up

From putting other people down

It’s clear to see by the air I breathe

Working class solidarity

Is the only way

We’re gonna stamp that fascist out

Sardonic and irreverent, “Outlaw Country” is an anthem for anyone who ever believed in love and community over corruption and power. But rather than a callback, Earl’s music is of and for the next generation of ne’er-do-wells and dreamers living on the fringes, hoping for something better.

Earl grew up in Lake Charles, Louisiana, where he split his time between separated parents. Chafing at the craven habits of money and influence that he witnessed from his father, a powerful local lawyer, Earl preferred the warmth and love he felt in the house his mother shared with his grandmother. (Despite a rocky childhood, Earl’s now building a relationship with his dad.)

“I was living in poverty on one side and then I was living in opulence on the other side, and the poverty side is where I wanted to be, because that’s where all the love was,” Earl says. “I’m so lucky to have that, to be able to have identified where love was at a young age and identify where my soul felt good.”

Earl’s mother showed him how to seek joy and adventure, filling life with road trips and camping weekends. When he was just five years old, Earl’s mother plopped a map in his lap and taught him to navigate. Perpetually tight on money and resources and mired in an enduring custody battle with his father, she nonetheless taught him how to get away from it all, instilling in him a curiosity about the world. On the road, they stopped to check out historical markers, explored parks and rivers and the Gulf Coast, and watched giant boats come in while picnicking along the Intracoastal Waterway.

“That developed a sense of wonder and being like, ‘I don’t fucking need money to feel this type of happiness, to feel this sense of joy and adventure and love of life, just life in its purest form,” Earl says, choking up. (He firmly believes more men should cry, and that it helps him be more humane.)

“Her sense of adventure, her true passion for living, it’s amazing to me; it still is amazing to me.”

The album’s title and thematic heart – level-headed even smile – are derived from that approach to living life fully. For Earl, it’s an essential mechanism of coping and connecting. Remain engaged in the world and aware of all its horrors and tragedies, he says, but then, when it gets to be too much, know when and how to take a break:

Some nights I’m crying on the backroads

Rolling my smoke backwards

Trying to keep a level-headed even smile

Don’t you know I might take a while to get there

Just hoping I get anywhere

Trying to keep a little level-headed even smile

“At some point we’ve got to unplug from the fucking screen and just go explore things that are fucking real, like the trees around us, or the grass, or the water, or the sun or the moon, and try to get in touch with that more primal sense of ourselves,” Earl says. “That is where we can really most quickly and most efficiently achieve happiness, it’s getting in touch with the simplest form of ourselves.”

Beside the love from his mother, Earl describes himself as a depressed kid who struggled in school and wanted desperately to escape his hometown and father and stepmother. At 15, he convinced his father to send him to boarding school which, in part because of Hurricane Katrina’s devastation of Louisiana, ended up being in rural Arkansas. At the Subiaco Abbey and Academy, Earl studied with monks who’d taken a vow of poverty and offered rigorous, benevolent study, kindness, and care. Though he’s an atheist, Earl counts the monks, whom he visits regularly, as mentors, connecting with them still through shared spirituality.

“We all fucking showed up pissed off as hell. And we found love and we found love amongst each other; we found love from those monks and found nature,” Earl says, reverently, of his time at Subiaco. “It saved my fucking life. The whole thing; I found joy and happiness for the first time in my life.”

Level-Headed Even Smile is dedicated to Earl’s late friend, William, who was the first to befriend him at Subiaco. “He helped me clear my heart,” Earl says. As he sings of those halcyon days on “Two Kinds of Loner,” “We were two kinds of loner/ A misfit and a wayward son…”

Armed with the sense of wonder his mom taught him, liberated by the fallow morals of youth, and subsumed by the ready escapism afforded by their surroundings, Earl and William learned every back road. They’d steal beer from the back of William’s dad’s Crossroads Tavern and drive for hours exploring the backwoods and levees along the Arkansas River.

“William was the first to show me the country air. Hanging out with him, something about getting in that truck after class, taking off down Lile Ridge Road, cracking a beer, putting on whatever weird music he was listening to at the time, that was the first sense of fucking true freedom I ever had in my life,” Earl says.

Stopping just shy of wistful, “Two Kinds of Loner” is a bittersweet, intimate portrait of the desperately important work of becoming oneself as a teenager – and of the raw beauty in forming kinship through human connection rather than blood relation:

Down where the kudzu meets the bodark

And the darkness first let go of me

High in a cab of a buddy I had

He showed me the county air

I used to not care about nothing

Because no one seemed to care for me

After high school, Earl attended Hendrix College, a liberal arts school which lived up to its name situated in Conway, Arkansas. A few years earlier, Earl borrowed his father’s old guitar – a Yamaha FG 180 Red Tag, which he still plays today – and learned enough chords to make himself useful around a bonfire and impress the local girls. Encouraged by one of the monks at Subiaco, who noticed him straying from lesson plans, Earl started writing his own music.

When he got to college, he landed feet first in a robust DIY music scene. Together with a group of friends – including Gar Hole Records cofounder and label manager Kurt DeLashmet – Earl played a circuit of local house venues: White House, Blue House, Brick House, and occasionally Shit Mansion, where both also lived for a time. To this day, their two-day, 28-band Butt Ranger music festival thrown by friends at the White House remains one of Earl’s favorite shows.

“We were drunk off our fucking asses on plastic bottle whiskey and snorting Adderall and fucking ripping cigs and shit like that. It was fucked up. It was so awesome. It was just blood and piss everywhere,” Earl says. He recalls the floor at White House buckling so deeply that by the end of the night all his gear, including his oversized amp, wound up in a pile in the middle of the floor. Volume was of primary concern, tone and other nuances distinctly secondary. “What a fucking beautiful, carnal, amazing culture to be a part of,” he says.

Two songs on Even Smile come from those early days playing music first in college and, afterwards, in Little Rock, where Earl and his band Swampbird moved. (Earl lived in Little Rock for a few years then moved to Fayetteville, where he still lives.) Both songs are paeans to the chaotic moil of early adulthood rendered heady and hazy by too much booze and too little grounding: “Broken Parts,” which he first recorded with Swampbird, and “Little Rock Bottom,” about his time in Arkansas’ capital city.

“I don’t really quite realize it until I am talking about it, how much of my life and my story is wound up into that album,” Earl, who’s now in his mid-30s, admits. The album feels like a fitting way to process and close that chapter of life. “I do feel like I’ve left it on the table and I’ve left it all out on the field, so to speak.”

In total, Even Smile is a loving, layered depiction of both Arkansas specifically and the south in general. Among his many influences, Earl includes Arkansas gonzo poet Frank Stanford (who also attended Subiaco and whose burial there Lucinda Williams memorialized in her song, “Pineola”). Stanford’s realism and wild abandon creep into Earl’s songwriting sensibilities; they share a love of the South and its complexities and a reverence for and dedication to illuminating those stories.

Alongside a few cheeky disquisitions on life on the fringes – including road dog ode “Get In The Truck” – throughout the album Earl relishes the beauty of his home territory. Perhaps nowhere more so than on “High On The Ouachitas,” an extended soliloquy on the wild beauty of the mountain range, his chosen retreat for a reset and solace:

When I’m high on Ouachita

High as I ever saw the Arkansas

With goldenrod and reindeer lichen

Twist flowers in bloom

There’s just no place

I’d rather waste my afternoons

Than high on Ouachita

“I love it so fucking much, because I know all of the nuance and I know all the beauty that’s deep underneath all of the stereotypes. And just how fascinatingly complex our communities are,” Earl says. “It’s fucking beautiful. You have two and a half million acres of national forest. So we have the cleanest drinking water in America; we have endless amounts of outdoor recreation; the food is fucking kick ass; the people are the sweetest ever.”

Earl rounded out Level-Headed Even Smile with two very on-theme cover songs: beloved Arkansas folksinger Jimmy Driftwood’s “White River Valley,” a love letter to Arkansas’s pastoral beauty, and Utah Phillips’ peripatetic wanderer’s lament, “Rock Me to Sleep,” which concludes the album. Together they bracket the glib “Lawn Chair,” written with Cameron Duddy and Jonathan Terrell.

Earl jokes when playing the song live that it might be the worst song he’s ever written. And superficially it sounds like the kind of redneck anthem that might confirm the uneducated listener’s worst stereotypes about uncouth Arkansans: “It’s a whipass life just being me/ It don’t cost much to be the free/ I got my lawn chair/ And I’m sitting on top of the world.” Yet the song is also a sly rebuke against taking everything too seriously. Convivial in its roughness, it’s a gleeful, carefree reminder of the many ways to keep a level-headed even smile.

“If I’m feeling bogged down and feeling depressed, oftentimes it has nothing to do with the task at hand, it’s just that I’ve been absorbing how terrible the fucking world is and it makes me incapable of interacting and interfacing with my immediate world, because I’m so fucking caught up in that goddamn bullshit… and it is not allowing you to reach your full potential as a biological piece of anatomy that is somehow living on this planet,” Earl says.

“[A level-headed even smile is] an attempt to focus on your humanness and try to reattach yourself to the earth and detach from the problems of the earth; and just go out and find your smile. Go find your joy amongst all the fucking evil.”

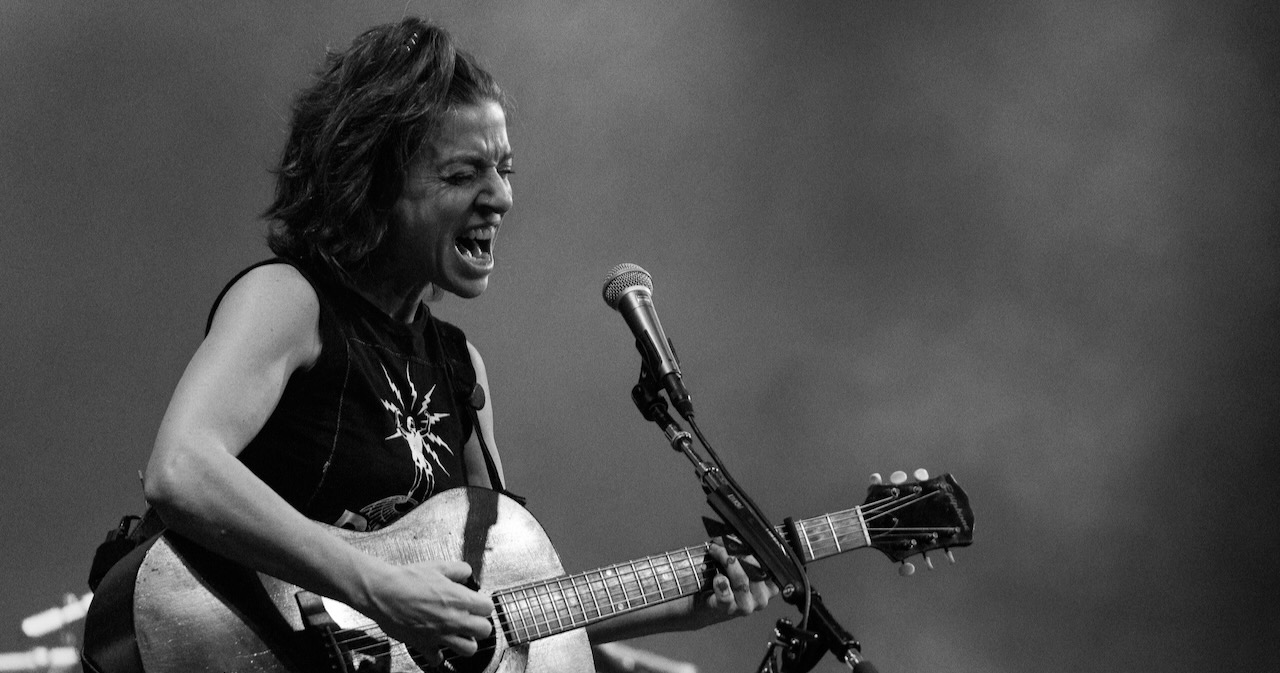

Photo Credit: Justin Cook