It makes some sense that you can’t really pin The Infamous Stringdusters down to a single place – you’ll find members in Colorado, North Carolina and Long Island, New York – because they are always on the move. Together since 2006, they have charted a sprawling course onstage and also through a dozen albums.

This year finds them on the road once again, showing off their 12th and newest album Toward the Fray, which has the most overtly socio-political songs they’ve ever put out into the world. In the midst of their touring schedule, they’ll also attend the Grammy Awards to see if last year’s A Tribute to Bill Monroe wins best bluegrass album. It would be their second time winning that category after hitting paydirt with 2017’s Laws of Gravity.

We caught up with the Stringdusters for a series of three conversations on the road (Zooming in from Louisville, Kentucky, Birmingham, Alabama, and Atlanta). Here is part one with guitarist Andy Falco and Dobroist Andy Hall.

BGS: Since you were quarantined for much of 2020 and 2021, everyone was doing their songwriting separately rather than together. Is that typical for the Stringdusters’ process?

Andy Falco: Typically we do write separately, and pre-production is when we come together. We’ll do a show-and-tell with songs, just playing guitars, and we might end up with 25 songs from that and start narrowing it down. It had to happen quicker this time once we got together, but there was something great about that, actually. Sometimes that initial spark of instinct will carry you through if you have to rely on it. We have instincts as a band, after putting in the 10,000 hours, and we did not have time to do any deep dives on changing things around. So we went more with instinct. There’s something special with this record.

View this post on Instagram

Andy Hall: It is a little scary to show off your songs to everybody that first time, but it’s exciting, too. You’re presenting your song for judgment, no way around it. It’s up for review and interpretation, the five of us sitting around playing acoustic guitars, and it’s not like there’s clapping at the end of it.

Falco: Sometimes you’re laughed out of the room.

Hall: Sometimes! What you hope is for everyone to say, “That was cool.” Or a quiet, “Yeah, nice.” It can be hard for me to know when I’m writing a song if it will work with the band. It sometimes surprises me what the band will like as a whole, which makes it exciting and interesting. I continue to be surprised in a good way, and I trust the band. Whatever the band picks tends to work well even if it’s not totally understood at first.

Falco: Sometimes what happens is it takes a couple of records for everyone to get on-board with a song. The band evolves and sometimes songs that don’t jibe at first, we’ll come back to them and they work. You never know.

Hall: It can be hard to say why it’s like that sometimes. One record, a song might not make the cut and the next, everyone is super-stoked about it. It’s all about the band’s evolution, and current mood. That’s what’s cool about the get-together pre-production part of the process. That’s where you have to have trust, and it gets easier as we get older. My trust in the band’s taste grows as time goes on.

As befits the Stringdusters’ most political record to date, it’s got quite a dystopian cover illustration.

Hall: It was shocking initially, but that’s kind of the idea — for it to be shocking and striking. Uncomfortable, that sort of vibe. I like doing things that might not fit in bluegrass, which is part of the reason why I’m covered in tattoos. I like things that are kind of metal, so doing something that’s not common in bluegrass really excites me. That part of it spoke to me. Bluegrass covers are generally middle-of-the-road. I like that we maybe ruffled some feathers.

Falco: When that cover was first floated, I was honestly not sure about it. Then after I sat with it for a while, it made sense. It was Andy Hall’s vision to put that together. We’re talking about things that are uncomfortable, and that suits the overall message of the record, to approach uncomfortable subjects. That’s what the song “Toward the Fray” is all about for me. It was inspired by the George Floyd situation and I wanted to say it’s not enough to denounce that, you actually have to engage with it. That’s where the cover does what it’s supposed to do, and I love that it’s gotten more comments than any other cover we’ve ever done.

Given the Stringdusters’ stature in progressive bluegrass, going straight-ahead old-school with last year’s Bill Monroe tribute seemed unexpected.

Falco: We talked about that a lot in the past, that we should do a traditional bluegrass record at some point. But every time we went into the studio, we had stacks of our own songs to do. Then when we were grounded at home during the pandemic, trying to figure out things to do, we were able to record remotely. The first thing we did was the Christmas record and then it was, “Let’s do that bluegrass record, a Bill Monroe tribute.” It was all done remotely. Neither one was reinventing the wheel, it was playing music we’ve played a lot over the years. Everybody knows their role and we were able to do that, as opposed to original Stringdusters music, where we have to be together for the improvisational elements.

Hall: To me, this was long overdue. The first bluegrass I ever owned was a Bill Monroe box set, so it’s the first bluegrass I remember hearing. I played with Earl Scruggs, Jeremy Garrett played with Bobby Osborne. We all cut our teeth with traditional bluegrass. It’s what informed us musically.

Congratulations on another Grammy nomination. Will you go to the ceremonies in Las Vegas?

Falco: Oh, yeah!

What was it like to win one?

Falco: I remember sitting in a row with the guys and you could feel everybody’s seat shaking. Then when we won, it was an amazing, incredible moment. It was an honor, and everything you’d think it would be. Plus it was at Madison Square Garden in New York, which was extra-special for me because it was like being at home. It was really great to share that moment together.

Did winning a Grammy change anything for you?

Hall: It helps. I don’t know how, but it seems like it does. People talk about it, yeah, and it gives you a moment of validation. There’s a lot of uncertainty in the music business, a lot of time spent wondering if something works – are we doing the right thing? What about the future? But winning a Grammy was just a moment of feeling like what you do is resonating. It’s a nice spark, something that goes right and keeps you rocking. Still, you just go right back to work. But that moment of recognition and success sure helps put some gas in the tank.

How do you manage the long-distance relationship of being in a band but living all over the country?

Falco: Living around the country, it’s important to stay connected creatively. So the holiday and Bill Monroe records served a purpose mentally. We weren’t just sitting on our hands waiting out the pandemic, we were creating during that time, which was important for our mental health. I was mixing at my house and when parts would come in, I’d put them into the track. What started with a rhythm guitar click track morphed into the Stringdusters sound. Those moments felt like we were making music together, and we were, just in a different way.

Given that you’re putting some definite socio-political content out with “Toward the Fray,” do people come around after shows wanting to argue?

Hall: Not too much. It’s presented in such a way that it’s all in context for people interested in the band and our music and what we have to say. Now if we were shoving messages down everybody’s throat on social media every day, I’m sure there would be more arguments happening. But that’s not how conversation should happen. Our job is to write songs expressing our feelings and put them out there, create work based on how we feel and what we think. That’s what we’ve done with this album and there’s not been a lot of pushback. What is there to argue about? It’s what we’re feeling, are people going to say no, it’s not? It is what it is. I hate arguing on social media, which never helps. Just create the art and move along.

Falco: As long as it’s genuine, you can say whatever you want about the feelings you’re putting out there, and then it’s all fair game. It just needs to be genuine because that’s the only way to write songs and play music.

Want to win tickets to see the Infamous Stringdusters at the Echoplex in Los Angeles? Enter our ticket giveaway.

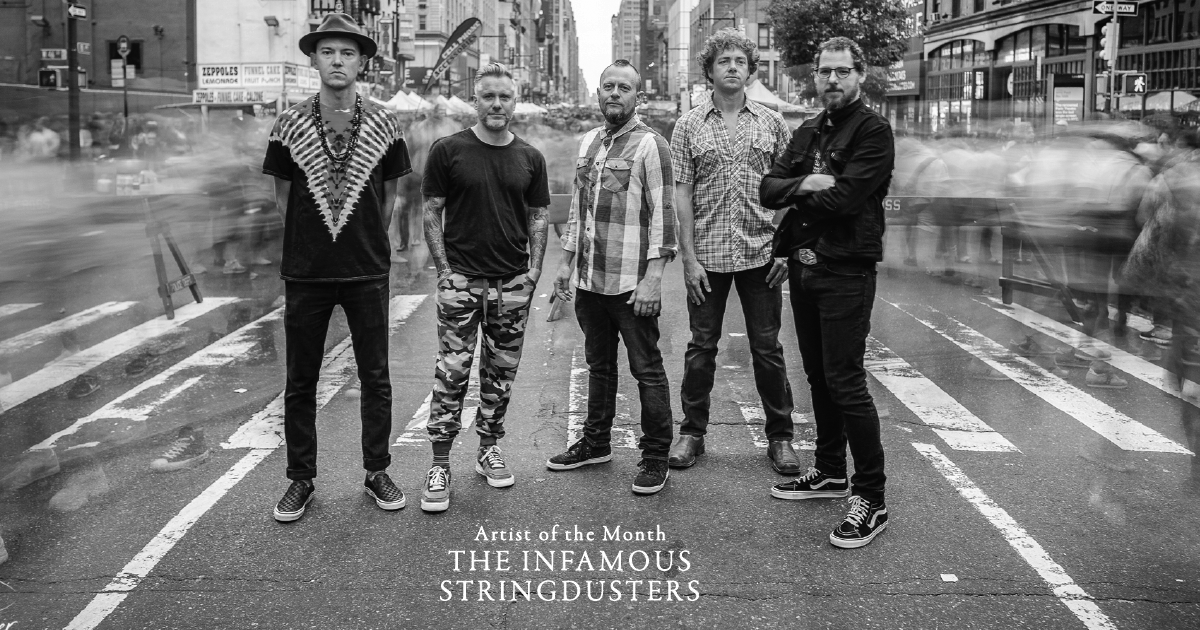

Photo Credit: Jay Strausser Visuals