Welcome to Deep Sh!t where, each month, I’ll hop on a conference call with two different folks and delve into perspectives, philosophies, and priorities that’ve somehow shaped what they each do. There’s really no telling where it could lead, which, for me, is a big part of the appeal.

Roots music really isn’t the place for artists who fancy themselves lone wolves. We tend to be a little skeptical of acts who’d have us believe that they sprang up sui generis, who refuse to acknowledge that what they’re doing came from somewhere, that they have predecessors and peers, shared springboards and sources of inspiration, templates and traditions to toy with and confront. It’s a welcome thing when roots music comes packaged with historical and personal narratives that lend it richer context.

Nobody makes a more joyful or dignified affair of that act of positioning than Sweet Honey in the Rock. A documentary shot a dozen-or-so years ago on the group’s 30th anniversary tour captures the grandness of the six women who comprised the lineup, at the time, striding out onto a theater stage, resplendent in boldly colored robes and headdresses, taking their seats in a semi-circle, and launching into one of their original a cappella spirituals, voices united in whirling, rippling conversation.

For more than four decades now, they’ve carried on African-American a cappella traditions without allowing themselves to become the least bit constricted by the forms; the new jack swing-ish groove beneath “A Prayer for the World,” a track on their new album, #LoveInEvolution, is hardly their first flirtation with contemporary instrumental accompaniment. Sweet Honey’s forged a musical identity capacious enough to celebrate a couple of centuries’ worth of Black innovation — from slave spirituals to Civil Rights anthems, from sanctified blues to quartet gospel, from folk to jazz, reggae to R&B, neo-soul to hip-hop — and to make room for the performing personalities and timely social and spiritual concerns of each of the 24 women who’ve passed through the group to date. Founding member Carol Maillard puts it this way: “We’re really an alive, living group. We’re always trying to find new ways to express. We’re not an oldies group.” What they are is something closer to a utopian singing community.

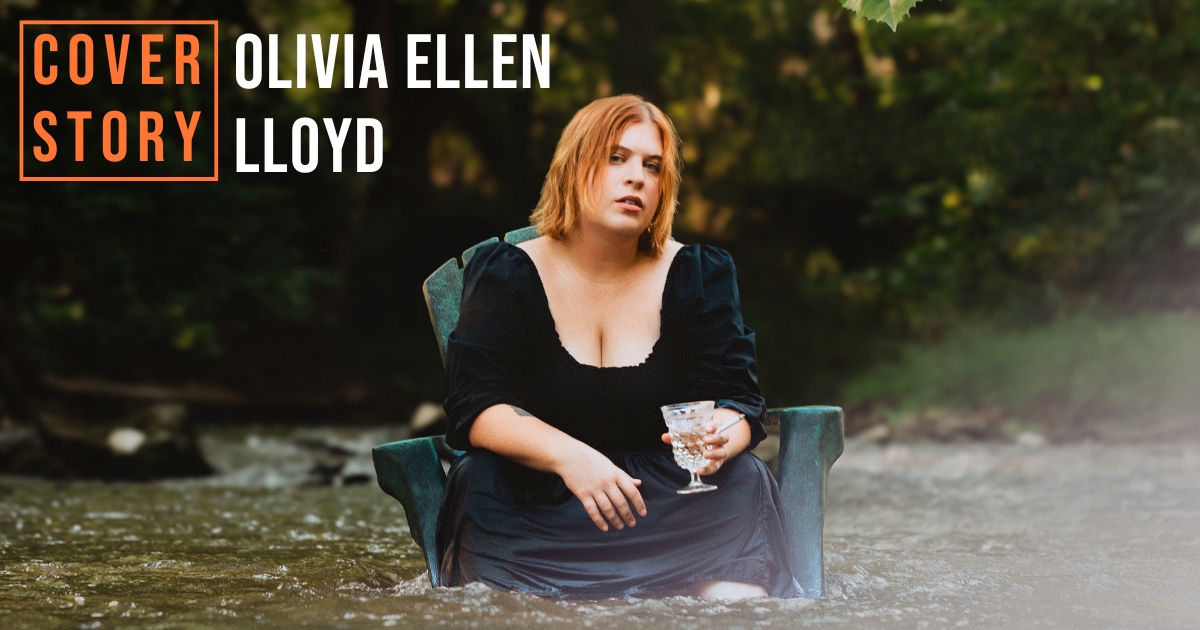

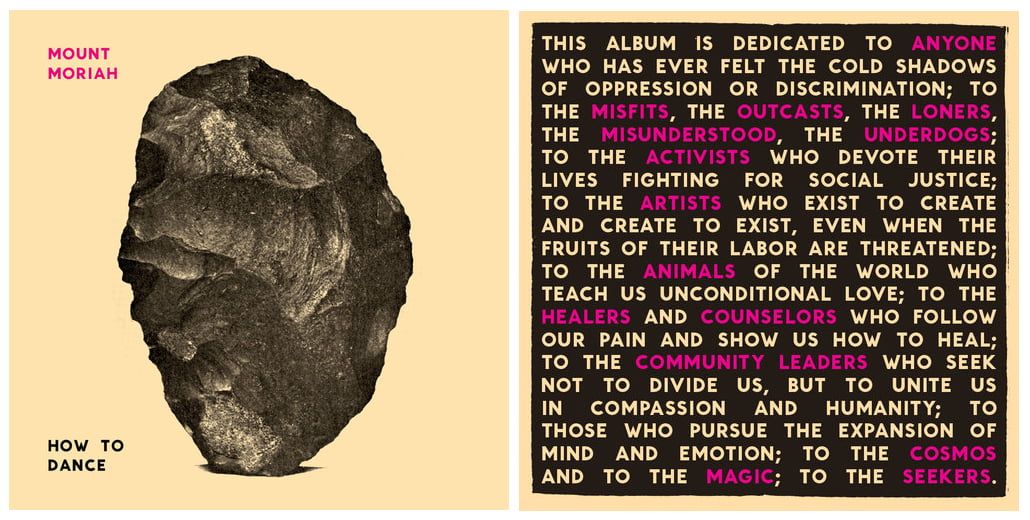

Mount Moriah have an entirely different angle on conscious music-making. The Southern indie rock outfit has been around roughly one-tenth as long as Sweet Honey, staking out territory first opened up by the Indigo Girls and Drive-By Truckers, pairing front woman Heather McEntire’s vinegary-sweet vocals, geographically specific vignettes, and blending of confession and conviction with brambly, lolling guitar twang. In her lyrics, interviews, and activism, McEntire often works to bring overlooked experiences of unambiguously Southern, church-spurned, openly queer women to broader awareness. She says of Mount Moriah’s upcoming album, How To Dance, “It’s a bit of a call to arms, inviting those people to show up and represent themselves, to unify.”

There was a time when McEntire felt alienated from music that shared any DNA whatsoever with country and its rootsier cousins, having found little she could identify with in what struck her as oppressively conventional depictions of relationships. Punk and avant-garde music became her early outlets in a band dubbed Bellfea, before she and her band mates decided to take that well-trod path from noisy transgression to molding countrified elements into a scrappy hybrid that suits their misfit identifications. And, unlike many others who’ve made similar moves, she expresses a desire to someday, somehow connect with a mainstream country audience.

The divide between Mount Moriah’s conceptions of community and Sweet Honey’s is vast, to be sure, but it proved to be bridgeable when McEntire, Maillard, and another of Sweet Honey’s singing co-founders, Louise Robinson, got on the phone together a few days into the new year. In their own ways, they each showed great generosity of spirit — the elder women sounding sanguine and seasoned, the younger more circumspect about the subversive qualities of her work. By the end of the conversation, the three of them were comparing calendars to see when their tour schedules would have them in the same city.

Carol Maillard and Louise Robinson, meet Heather McEntire. Heather, meet Louise and Carol. You haven’t had any occasion to meet in the past, right?

Heather McEntire: Not yet, no.

You might think that you’re kind of unlikely conversation partners but, from my perspective, you both make music with community in mind — communities it’s from, communities it’s for, communities it represents. I want to talk about how and why you do that.

Neither of your groups were formed in a vacuum. Mount Moriah has roots in North Carolina punk scenes and Sweet Honey came out of the Black Repertory Theater in D.C. Carol and Louise, how did your theater origins shape the group?

Louise Robinson: We were actors in the company and, to be in that company, we had to take a vocal class, along with dance. … It was a young man [in the company], actually, who had the idea of, “Let’s put a group together.” He called me on the phone and said, “What do you think?” And I said, “Yeah, let’s do this.”

At the time, Bernice Johnson Reagan was the vocal director. We asked her to help us with this group. So the group actually started with both men and women. As the rehearsals went on, fewer and fewer people showed up, until one day there were four women left on stage. That was the beginning of Sweet Honey in the Rock.

What skills and resources do you feel like you brought to the music from your theater training?

LR: I think, with music, you’re telling stories. If you want your audience to understand what you’re talking about, then you have to, I don’t know if I would say act out, but you certainly have to put some passion and expression into the words that you’re singing. … To train as an actor, teaches you that each word has a lot of power. You want that feeling to transfer from the stage to the audience, you know, from heart to heart, from mind to mind. There are things you want people to think about, things you want people to feel, things you want people to remember. Those are the same skills that you use in stage acting.

Mount Moriah: Heather McEntire, Jenks Miller, and Casey Toll

Heather, I’d love to hear about your transition from one scene to another. How did your years in punk and avant-garde scenes prepare you for what you’re doing now?

HM: I feel like, with Mount Moriah, particularly this last record, we wrote it representing kinda the misfits and the folks on the fringe. I definitely experienced that in the punk scene: D.I.Y. venues and incredibly creative people who just kind of built their own platforms. I met my band mates at a punk rock show 15 years ago in my basement.

Of course, Mount Moriah isn’t “punk” within genre, but I think there are a lot of ways to be punk. I feel like we embody a lot of those values and wanting to do things as much on our own and have creative control and just be super-aware of our band identity and who we’re reaching and how we’re doing that.

All of you started out representing musical identities that weren’t necessarily being widely represented at the time. The lineage of African-American women’s a cappella groups, for instance, had sort of faded from view by the early ‘70s when Sweet Honey got going, and songs of the Civil Rights movement were no longer being sung like they had been. Louise and Carol, what sort of responsibility did you feel about extending those traditions?

Carol Maillard: I didn’t particularly feel any way about it, one way or the other. Because, when we started, a lot of the music was coming out of folk — the idea of the troubadour and telling a story and talking about social issues that happened in the late ‘50s and ‘60s. A lot of groups toward maybe the later ‘60s really started to talk about things that were going on — groups from folk to rock, R&B, soul music. Everybody started to talk about the issues. So we weren’t really conscientiously going, “We’re gonna sing these particular kinds of songs and preserve this stuff.” I’m talking in the beginning, because I left the group in ’77 [and later returned].

We always wanted to sing about stuff that mattered to us, things that made sense in our community and in our souls, in our bodies, in our womanhood. We always wanted to sing things that made sense and connected us to a particular mindset. So we were coming out of not only the Civil Rights tradition — we were coming out of the Stevie Wonder tradition and the Marvin Gaye tradition, and we were with the Isley Brothers and Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young … Earth Wind and Fire, people who were singing about things.

LR: One thing to realize, Sweet Honey has been around 40 years, 42 years. We have had 24 different women in the group, and every configuration has always embraced the women that are in the group. So, like Carol says, we bring in to the group all these different experiences. So the totality of any one [lineup] is shaped by the women that are on stage singing, where they’re coming from. Some come from the city. Some come from the country. They’ve had various experiences.

Not only have you made room for two dozen women to bring their contributions to the group over the years, your vocal arrangements often set up an animated dialogue between your voices, a tapestry of harmonic ideas, a call and response. Plus, each member gets her chance to shine as a soloist. Do you see yourselves as performing a vision of community?

LR: Always! I think you have to [look at it that way], especially if you’re singing a cappella. Your voice is your instrument. It’s in your body. You can’t put it down on the shelf. You can’t put it in the case and put it away. It’s you. The closest instrument to you that you’re gonna get is your voice. You have to embrace yourselves as a community because, when you lay out a song, everybody’s a part of the whole. If a part’s wrong, the song is wrong. If a part is out, the whole song is out. Then you’re trying to communicate to a community, whether it be a local one or a world one. So the answer is yes. You always have to consider community.

Sweet Honey in the Rock: Aisha Kahlil, Carol Maillard, Louise Robinson, Shirley Childress, and Nitanju Bolade Casel

You have a member signing for the deaf when you perform, so that’s yet another community that you’re speaking to. How’d you first incorporate that into your performances?

CM: I think when Sweet Honey went out to the West Coast in the late ‘70s — I wasn’t there — they had a tour of some sort with some feminist groups and women’s groups, and they noticed that that these festivals and musical gatherings always made sure that it was possible for everyone to be included in the audience, which meant there was gonna be wheelchair accessibility; there would be a sign language interpreter; there would be childcare, so that women could come to these events and feel comfortable, that they were being considered and looked out for.

At that time, they thought it would be a great thing to do to have somebody to do that [in Sweet Honey], but I think it took them a little minute to find somebody. The first person was Ysaye Barnwell. Bernice went to church one Sunday in Washington, and Ysaye just happened to be a member of that church. She was signing and singing at the same time. Bernice always said that her signing had a real wonderful rhythm and a cultural element she had never seen expressed in sign language, and she asked Ysaye to be the sign language interpreter. And, finally, Ysaye realized she couldn’t do all that at the same time. So she asked Shirley Childress if she would be the sign language interpreter. Shirley’s been with us since 1980.

That’s pretty amazing that that much thought was being given to removing any and all barriers to people enjoying the music. Even now, I think that’s rare.

CM: Right, right. Shirley often said that deaf people, and maybe hard of hearing as well, it’s like, “Why should I come to a hearing event? What is it gonna do for me? What am I gonna get from it?” But once they come to a Sweet Honey event, they realize that their issues or their thoughts and feelings — political, social, cultural, whatever — are being addressed. And Shirley is so amazing at what she does, it’s really hard for anybody to miss what’s going on.

LR: She sings with her hands.

While we’re on the subject of representing musical identities that are lacking in the landscape, Heather, you launched Mount Moriah at a time when some people still couldn’t picture an artist who’s an openly queer Southerner expressing herself through roots or country-leaning music. How’d you embrace the idea of putting yourself out there in that way?

HM: Well, I had to really get my brave game goin’. I grew up in the mountains here in North Carolina. I grew up on country music and old-time and gospel. With the country music that I was listening to growing up, I mean, the melodies were amazing, the harmonies were amazing, but I never felt like those stories were mine. And I knew that I couldn’t be the only one.

It was a very strategic thing for us to decide to make music in this style and format. It’s much more accessible than anything I’ve done in the past, stylistically. That’s part of why we do it — because I want to reach those people who are listening to country stations. I want that crossover to be there.

You’re several years into this now, about to release Mount Moriah’s third album. What’s come of your desire to connect with new audiences?

HM: When people hear Mount Moriah, I think they hear my voice. There’s a familiarity with it, just with the format of songs, you know, like, verse-verse-chorus-bridge. So it’s easy for them to take in, in a way. It’s been pretty powerful to see the reach we’ve had across communities, ones that I never thought would intersect. That’s what makes me want to be in this band and write music for this band and share these narratives that are socio-political, but they don’t hit you over the head with it. You kinda get hooked in a little, and then [you hear] the lyrics. It’s not a trick, but it’s certainly strategic, the style in which we write.

On the first couple of Mount Moriah albums, you had narrative-driven songs like “Reckoning,” “Those Girls,” and “Miracle Temple Holiness” that told stories of queer Southernness and social alienation. The lyric writing on the new album, How To Dance , seems to have taken a little more of a mystical turn. How does the idea of getting a message across come into play for you?

HM: I went to school for creative writing, so that’s my first love. Writing these narratives and trying to find a way to make impassioned ideas poetic is a big challenge for me, but that’s what keeps me in this band. [I made] the conscious decision to use a pronoun like “she” instead of just leaving it open, which, honestly, I do more of that on this record, which says a lot about where our society and culture have progressed since our first record. On the [new] record, I didn’t feel like I absolutely had to do that, and that there was more of a power in just representing this universal relation.

LR: Mmhmm … Everybody.

HM: But I remember I was really, really nervous when I first wrote the song about coming out to my mom. I could’ve easily, in many of the songs, just not used a pronoun, but I felt like people needed to hear that. It’s something I wished I’d heard growing up, just being able to have a story that you can relate to. For me, it’s been really empowering, coming out and staying out and representing that part of the community. I feel a responsibility there, and it’s something that I welcome and I feel grateful for.

Louise and Carol, how has your desire to convey a message guided the creative decisions that you’ve made in Sweet Honey?

CM: Oh wow, man! You know there are so many interesting things around Sweet Honey. This is just coming from me, my 20-odd years back with the group. A lot of stuff I think that we learn, or at least I learn, about Sweet Honey’s persona and the work that we do or the choices we make, I would say a lot comes from outside of the group.

What do you mean by that?

CM: What people tell us, what people write to us. They give you a gift and they put a card in it and they tell you a whole story about what your music has done. We have not, as yet, been a lot in the media and gotten lots of reviews and those kinds of things.

I think, for me, when I have to come up with a song or something, there are many things that come into my mind: “What do I want to talk about?” I don’t necessarily always want to talk about politics and social issues. I may be in my God vibe. I may be in my single mother raising a boy child in New York City vibe, and [want to express] that I might fear for his survival. I might have a feeling because Columbine happened. So I think, for each one of us, it’s very different. It’s really the women who are in the group, like Louise said earlier, that make a difference in how the group is presented. … We really do take it from wherever we are. We’re very present, I would say. Wouldn’t you say, Louise?

LR: Yeah, yeah.

CM: We’re very present because we’re trying to stay in the game.

LR: You wake up in the morning and go outside, and people have issues with people who have guns, which is political. If you live long enough, [you see these issues come full circle]. Now unfortunately it’s back again and there are racial problems. That’s real.

CM: It ain’t never going nowhere.

LR: You have people unemployed. That’s political. You have all this still going on. So life is political. All you have to do, really, is reach into your life and see what you want to talk about.

CM: This is my life, this is what I’m doing, this is what I’m into. I’m writing about that.

LR: It’s very personal. And, when you’re personal and you’re singing and talking and relating to other persons, then you have something for them that they can relate to. Sometimes we are talking about what it is to raise a child. Sometimes we are talking about the person we fell in love with and now they’re gone, or the person we fell in love with and we’re so happy they’re here.

The thing about Sweet Honey is it does take [different shapes depending on] who is singing on the stage. I mean, you’re gonna learn songs that have been in the repertoire … that, too. But, clearly, you’re invited to bring something to change the sound of the group and see what you have to add.

You were talking about living long enough for troubling issues to come back around. On your new album, there’s a song called “Oh, Sankofa” that contains the refrain “learning from the past” about that idea of retrieving history and making it present again. As many different things as you’ve done in the group, that seems like a constant: linking the past with the present.

CM: I love that “Sankofa” song. That’s a story [of the Tulsa race riots of 1921] a lot of people don’t really know. American history-wise, it’s historically very important to know that story and to be able to go back into it and see how it relates to where things are today.

What do you think is the importance of reminding ourselves of the past?

LR: So you don’t go down that road again, if you can help it. So that you might be able to make a choice where you’re not going down that same road, if you know what happened before.

When it comes to passing on knowledge, you’d done several recordings aimed at youth — put lesson plans in your liner notes and made teaching an aspect of what you do. What fruit have you seen your desire to educate bear?

LR: The fact that somebody could come up to us with a full-grown mustache and beard and tell us they grew up on Sweet Honey, and they look as old as we do.

CM: That’s right. That’s embarrassing, almost!

LR: … Somebody came to the [merch] table the other day — it was a grown person — and said, “I grew up on Sweet Honey in the Rock. I brought my three-year-old. I have a one-year-old, and when my one-year-old hits two, they’ll be introduced to Sweet Honey concerts, as well. … That’s the fruit. That tells you that it’s relevant and it’s been relevant through generations, and you get a sense that it can live on beyond you.

CM: Live on through their children.

Heather, you’ve had an educational outlet of your own through Girls Rock Camp.

CM: Nice!

LR: Girls Rock — is that your camp?

HM: Oh, it’s not my camp, but I worked for about eight years for Girls Rock N.C. based out of Durham. I think there’s a D.C. Camp, as well, I’m sure.

LR: There might be several up here.

HM: They’re everywhere, yeah. Empowering girls and teaching them about feminism and to be brave and just go for the strings. Even if you don’t know the names of the chords, put yourself out there. It definitely has informed me. Honestly, it’s held me up, too. It’s helped me to sustain my courage and to try to dispel any insecurities I may have. I look at the kids I teach and I think, If they can get up and do that, I can do that. It’s a very mutual relationship.

CM: That’s great.

This next question is for all of you: When you’re up there on stage looking out at the audience, do you see people who look like you? Do you see more people who don’t look like you? Do you want to see people who look like you?

CM: Our audience is vast. Sometimes, there’s all white folks. And, sometimes, it’s mostly black folks. Sometimes, it’s mostly college students. Sometimes it’s, you know, a lot of white hair from many races. It depends on where we are, who invited us, and the venue. That’ll influence a lot. When I say our audience is vast, I mean that. You’ve got people who are scrounging money to put together to come to a show or got a free ticket. You’ve got people with big bucks and they brought 10 of their friends, people who are just coming for the first time, people who have been with us for at least 40 years. Students, older people, young folks, people who are educated, people who have very little education, people who are very religious, people who are atheists. They all come, and they all get that message — whatever it is that they need to feel within themselves about changing or acceptance, self-acceptance, self-love, loving others, love in action.

Heather, what does Mount Moriah’s crowd tend to look like?

HM: I guess demographically there’s a range, in terms of generational fans. But I would personally like to see a more diverse crowd out there. But I know, when I look out there, I see people that I love. I see a lot of young girls that are looking up and wanting to see — needing to see — someone that looks like them, something they can hang a dream on. I love seeing the punks who supported my old band, Bellfea. That always means a lot when that community still follows you into a new genre. Like [Carol and Louise] were saying, I get a lot of feedback from people of all spiritual beliefs, people who have faced different forms of oppression.

Illustration by the crazy talented Abby McMillen