Flatpick guitarist Tony Rice is a legendary figure in the world of bluegrass — one whose story is defined in mythic proportions, with language typically reserved for the hero of a literary epic. His D-28 Martin guitar, which once belonged to Clarence White, has been anointed “The Holy Grail,” and his acceptance speech during his Hall of Fame induction at the 2013 IBMA Awards has come to be known as “The Moment.” For nearly 20 years, Rice had been silenced by a vocal cord condition known as muscle tension dysphonia. Holding his right hand to his chest, he announced, “I am speaking in my real voice,” to a crowd filled with applause and tears.

Now, Rice has lent his voice to another poignant IBMA Awards moment — this time on behalf of his dear friend and personal hero, guitar pioneer Clarence White. White will be inducted into the Bluegrass Hall of Fame at this year’s IBMA Awards in Raleigh.

To kick things off, let's just start at the beginning. Can you tell me about the time that you first met Clarence?

There used to be a radio show in Southern California in Los Angeles where I grew up — it was called Town Hall Party. It would come on every Sunday afternoon; it was a live radio broadcast. Multi-talented, mostly country music, but there was a bluegrass band there, a band called the Country Boys, and my father used to listen to them religiously every Sunday. So one day, it was in 1960, my father got ahold of somebody over there and asked them if they could put me on the air singing a song. And so they agreed to do it and we went out back of the building where the bands could rehearse or do whatever they wanted to do.

But, anyway, my father and I went back there. There was this bluegrass band, the Country Boys — you know Clarence and Roland and Clarence's brother Eric on bass and Billy Ray Latham on banjo and LeRoy Mac was on dobro — and boy, what a sound! But it's like, just to see this 16-year-old guy — and I was nine years old at the time when Clarence was 16 — and he had this old guitar, this old ragged-out guitar … didn't have a name on it. I asked him … it looked to me a little bit like a Martin. And the only Martin I knew anything about, at the time, was a D-18 because my father had given me one. And I remember asking Clarence, "Is that a D-18?" and he said, "No, this is a D-28."

And from that moment on, everything was just fascinating. It was beyond description to see this guy sitting there that young and playing rhythm — that's the only thing he played at the time. He wasn't even playing lead. But to see this guy playing rhythm that precise with that much dedication, it was beyond description. And the rest is history.

We became friends because, at the time, there was only two bands — bluegrass bands — in the whole Los Angeles area, and they were the Country Boys and my father had just started a band called the Golden State Boys. Don Parmley would later on become a full-time member of the band and different people would come and go over the years: Vern Gosdin and Rex Gosdin were part of the band and what not. But there was only two bands there and then, I don't know, it seemed like bluegrass in general started to take off around that time and sort of run a parallel with the revival of the folk boom that was happening — the folk music boom.

And, well, the rest is sort of history. It seemed like everything started to grow and the White family and my own family became friends and, whenever we could see each other or visit or do whatever, we would get together any way we could. Well, then, we always did that.

What was it about Clarence's playing, specifically, that really resonated with you? Why was he such an inspirational figure for you, as a musician and even as a person?

Because he was different from anybody else that I had ever heard in a way that's very hard to describe. I mean, he didn't play rhythm like Jimmy Martin; he didn't play rhythm like Lester Flatt. He just sort of had his own style in a way that he … his own technique. And I don't even think it was something that he practiced. I think it was just Clarence White's musicianship. I tell people I think it was just in his DNA. He just played without guard to thinking about it so much, consciously thinking about it so much as to just be an integrated part of a band and enjoy himself and play rhythm guitar the only way that he knew how to do it.

Right. So obviously he had this profound impact on you. So, as your career developed, what aspect of his playing was always present with you? Was there anything that he did — like you were saying, sort of the way he played without guard — was there ever a part of you that tried to emulate that or sort of any approach that he took that you said, "I wanna incorporate this into my playing"?

Well, from that moment on, to somebody like myself, it's like, and being that young — as young as I was — it just automatically became a situation whereby I saw him and that old ragged-out guitar and I thought, "Okay, well, this is the way it's supposed to be done," because it sounds to me more pleasant than anybody else playing rhythm than I had ever heard.

Is there a particular piece of music that Clarence played that maybe moved you the most?

No, there really wasn't because, like I said, at the time, he wasn't playing lead guitar.

Mmhmm.

I remember this vaguely. It might have been a year or two after — or maybe even three years went by — and Roland got drafted into the Army and that left a void there of another instrumentalist that took solos as an integrated part of the band. And, you know, there were periods of time when they didn't have a mandolin player. Well, Clarence very quickly learned to take up the slack where his brother had left off and it seemed like it happened overnight. It happened so fast that this guy that, you know, I had no idea played any lead at all, it just seemed like, in a matter of weeks, he went from being somebody who didn't play any lead at all to being one of the most incredible, unique guitar players, in terms of his ability to play lead and still have it sound like it was a natural, integrated part of bluegrass music.

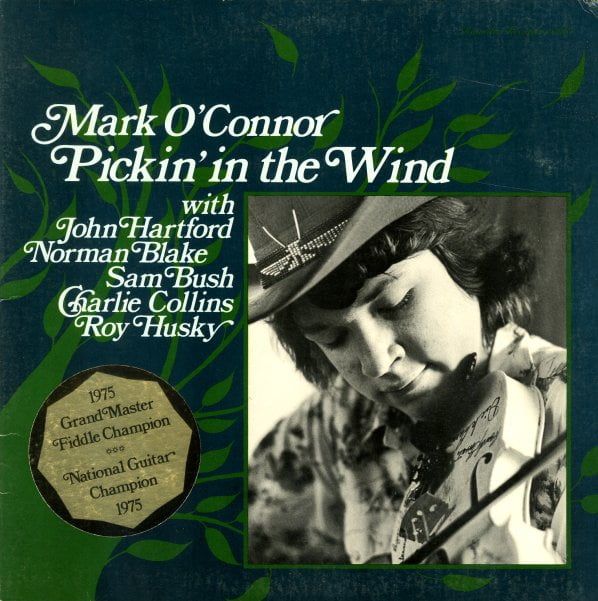

And geez, you know, when I think back at the years that went by before anybody else was even known about — and not that many people even knew about Clarence, in terms of his ability to play lead — and then, next, I think around 1963, Doc Watson would come along and a couple of other people people would come and become more familiar with Norman Blake. A lot of this stuff is hard to answer.

I know, it's hard to summarize what someone means to you when they mean so much. Well, we can't talk about Clarence without talking about the guitar a little more. I'm sure it's a story you're always asked to tell. Can you just sort of recap for me the story of how you came to be reunited with his D-28.

How I came to acquire it?

There you go.

Yeah, I can, although it's on the Internet about 500 times.

Clarence White and Roger McGuinn in the Byrds, September 1972. Photo credit: Dan Volonnino

Well, how about we do it this way: Why was it so important to you to acquire this guitar? How about we do it that way?

Because from the time I heard that guitar, there was something about every other guitar — and this exists to this day — that one particular guitar has a sound that's so unique that there's nothing else out there that can compare to it. It was dormant for about nine years, and the subject came up when I was with J.D. Crowe in the early '70s. Well, one of the members of J.D. Crowe's band was Bobby Slone. And Bobby was a fiddle player for a while with the Country Boys, who were then called the Kentucky Colonels. But the subject came up one night and Bobby says, "You know, I think I know where that guitar is." And, as it turned out, Clarence had either sold or pawned the guitar — one or the other, I'm not sure; nobody's sure.

Probably the best story I ever heard about it was from Roland White, that Clarence, around 1965 or '66, had started to take an interest in electric guitar playing. And it was actually discovered how good he was by a very renowned country electric guitar player named James Burton. And James Burton sort of took him under his wing and helped Clarence develop a unique style of electric guitar playing and Clarence went on to play with Ricky Nelson and various, different country bands out in the L.A. and Bakersfield areas. So Clarence didn't have any need for the guitar. And him and his wife, Susie, had not been together for a long time, but they decided that to get married. And there was a very renowned guitar player that played with Buck Owens that had a Fender Telecaster guitar that Clarence wanted. So Clarence sold the guitar so that he would have enough money to buy this guitar from Don Rich, who played with Buck Owens — so he'd have enough money to buy the guitar and an amp from Don Rich and also take him and his wife on a honeymoon.

And then what happened later on … like a sort of conflict happened or I have no idea, even Owens was vague about it to some degree. But nonetheless, it's like not knowing what happened, there's a reason why Clarence never was allowed to get that guitar back from Joe Miller. That's still open for speculation to some degree. But even after Clarence had joined the Byrds and acquired an enormous amount of money, he offered the guy that he sold it to — a guy named Joe Miller — who, Joe Miller was a guy, I think that used to play football for UCLA or something, but his family's very rich. Joe Miller's family owned a chain of liquor stores in Pasadena, California, and were very successful and very wealthy. But this guy Joe Miller was such a fan of the Kentucky Colonels that he followed them around everywhere. So Clarence ended up selling the guitar to Joe Miller and Joe Miller was the one who had it in his possession. In fact, the guitar was not played for about nine years when the subject came up, you know, as to who had the guitar, where it was, because the whole world thought the guitar was just inaccessible to anybody.

But where this story gets real interesting is, I played a very, very, very long shot. The next day after Bobby Slone told me who had the guitar was a guy named Joe Miller and he told me about his family and Joe Miller's family owned a liquor store, you know, called Miller's Liquor. Well, the next day at home, just to play a long shot, I got on the phone. I was living in Kentucky, at the time. So I got on the phone and I called information and asked them do they have a number for Miller's Liquor, and the operator said, "Yeah, we have nine of 'em. Which one you want?" So I said, "Well, give me the first one you got." Well, she give me a number and the first one I got, I called and I said, "Is Joe Miller there?" And the person that answered the phone said, "No, Joe is not here, but he'll be back probably in about an hour."

So I waited and called back: Lo and behold, Joe Miller was there. And I said, "Joe Miller," I said, "I'm in Kentucky. My name is Tony Rice and I play with a guy named J.D. Crowe." And Joe Miller knew all about the J.D. Crowe Band and knew who I was and everything. And I said, "Mr. Miller, I understand that you have the guitar — the old D-28 — that Clarence White used to have." He said, "Yeah, I do." And I said, "Well, would you consider selling it?" And, as best I remember, he said, "I wouldn't sell it to anybody else, but I would sell it to you," or that he would consider it. He said, "Before I do," he said, "I think it's only fair that I have it appraised to see what the value of it might be." And I thought, "Uh-oh. He's gonna come back with some figure that's gonna be off the scale that there's gonna be no way in the world that I could afford it."

But he came back, he called me back and he said he took it to the last place that Clarence had had the guitar worked on. And I can't remember that guy's name, where Clarence had took it. But the guy told Joe Miller, he said, "Well, this guitar is in pretty ragged-out condition," he said, "even though it is a Martin D-28," he said, "I'd say if it was in real good shape, it might be worth around $600, but in the shape that it's in," he said, "I would put it in the $450 to $500 range." And so I told Joe Miller, I said, "Well, Joe, would you be willing to split the difference?" He said, "Yeah," he said, "I think I could do that." I said, "Well how about $550?" And so we agreed on $550. Well, the next day I was on a plane from Kentucky out to meet Joe Miller with a guitar at a Sheraton Hotel at the airport in Los Angeles. And he brought it there and I brought the cash there and give him the cash, you know, got the receipt, walked out of there with that instrument for $550.

Wow, that's an incredible story. Thank you for re-telling that for me. Well, Tony, this has been great. I mean, we covered a lot of ground. I wanna thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me. It's really an honor and a pleasure.

Well, I hope I haven't overtalked myself here.

No, this was great. I don't wanna keep you too long. I could talk to you forever. But to wrap, if we wanted to get one cool, one great sound bite to summarize what Clarence meant to you, what would you say?

You know, I don't know. It's very multi-faceted. It's like if I were to ask you, "Desiré, do you know what a rose smells like?" And you'd say, "Well, of course." And then I would say, "Okay, tell me about it. Tell me what a rose smells like." Well, you wouldn't be able to do it, right?

Exactly.

There's no words, you know, in the English language, or in any other language for that matter where you could describe to me what a rose smells like. And I run into that situation a lot. You know, people ask me, "Well, what did Clarence mean to you?" and, you know, "How did you learn to play rhythm like him?" etcetera, etcetera, etcetera. There's some of those things that are just like the scenario with the rose. And one of my fellow heroes in music is a jazz horn player named Wynton Marsalis. And I seen him doing a lecture one night on a TV program and I never will forget this: Wynton Marsalis was the guy that said, "Well," he said, "Let me simplify this." He said, "There are so many things in all music forms that there is only one word you can use to describe some of the different facets involved in any music forms," and he said, "That word is mysterious." And such as the case, you know, as it is here. It's the same thing with my relationship with Clarence. We became friends and I never took a guitar lesson from Clarence White or anything like that. You know, we would sit down with a guitar whenever we could.

I do remember this very well: Whenever Clarence and the White Brothers and myself and my brothers ended up playing a lot of those places in L.A. — Ash Grove, the Troubadour, you know, so many places that were out there at the time. Whenever I was together with Clarence White and whenever we were at the same show together, I would always ask Clarence, "Clarence, when I do my show, can I play that old D-28?" and he never refused. I think it finally got to the point where, if he saw me coming, he just took it off and handed it to me.

But other than that, I really don't know. So many things that you know them in your conscious mind, but you can't put 'em in words. And you know, I wish there were more definitive ways of being able to answer a lot of the questions that a lot of people wanna know about my own relationship with Clarence White and what he meant and what he means today and you know, etcetera, etcetera. And I did go through a period where I wanted to play like him and would practice that and practice that and practice that and I think I was even into my mid-teens before I figured out I ain't gonna be able to do this.

And, as a result of my inability to play like Clarence White, out of that came my own identity as a separate musician from Clarence White altogether, with the exception of, you know, a few things like rhythm style and some of the techniques he used. The fact that Clarence had no fear of the guitar when it came to playing rhythm and throwing in different board substitutions and syncopations that had never been done in bluegrass before. I mean, he had no fear about throwing those things into a band. And, of course, later on, that's one of the things that I developed, too, is that lack of fear of the instrument. And, you know, the confidence to, whenever you have that confidence to play rhythm guitar as an integrated part of a band and do so in such a different way as to not step on anybody else's toes that are a part of the band, if I'm making any sense here.

Absolutely, you are.

And other than that, I don't know what to say.

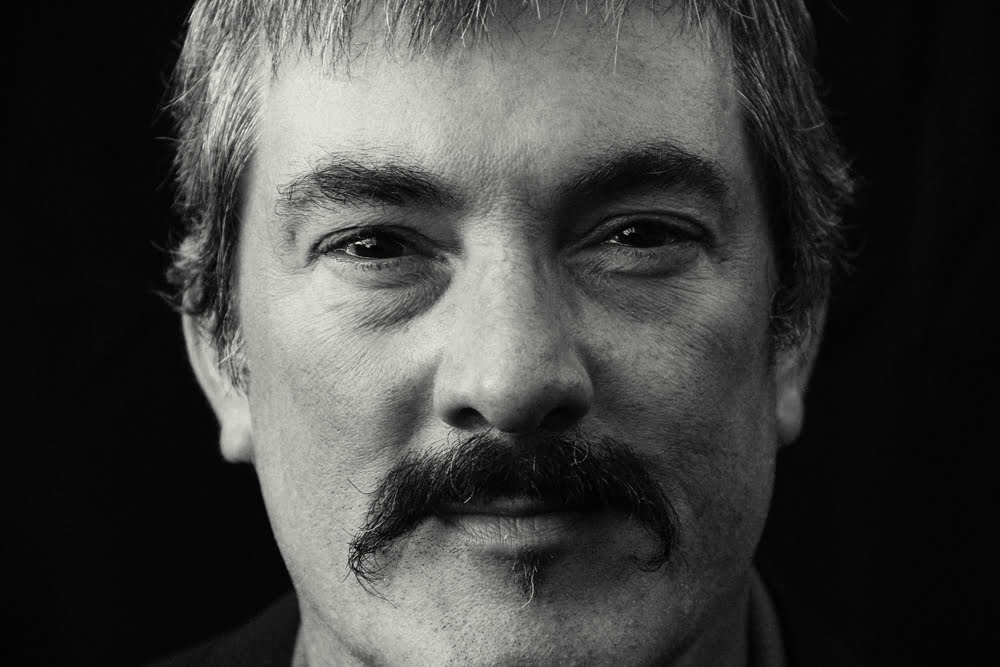

Lede image: Tony Rice, 2005 RockyGrass. Photo by Jordan Klein.