Anne Harris is having a moment. Though many people (this writer included) are just finding out about this Midwestern violin virtuoso this year, she has been making records since 2001. With her new album, I Feel It Once Again (released May 9), Harris decided, in her words, to “bring things up a level.”

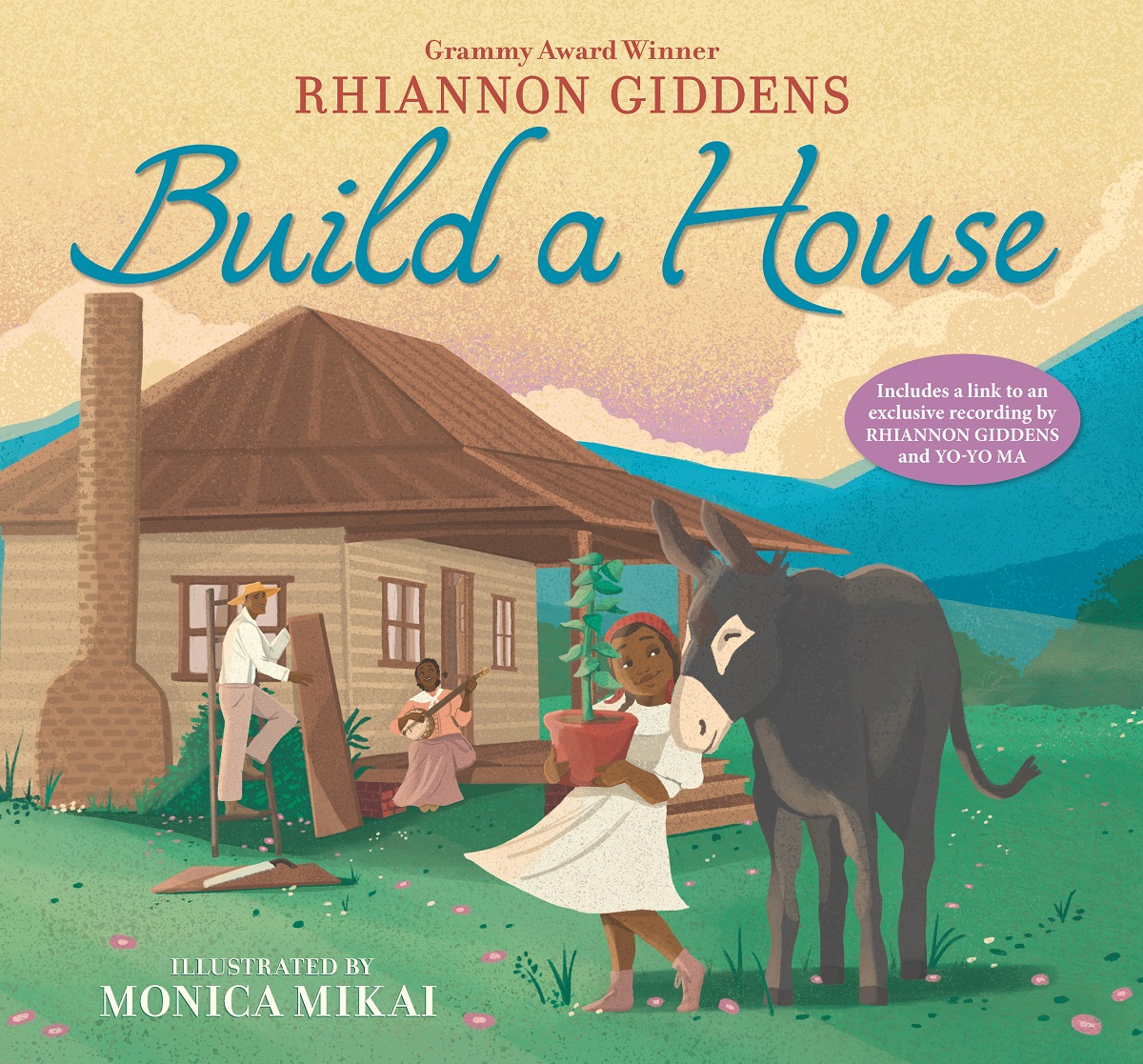

Not only is the disc getting rave reviews, it marks the first-ever violin commission in America between two Black women – Harris and luthier Amanda Ewing. The 10 songs on I Feel It Once Again range from traditionals like “Snowden’s Jig” and the closer “Time Has Made A Change” to originals like “Can’t Find My Way” and the project’s title track. Throughout, Harris remains impressive in both her vocals and her violin playing. The album was produced by Colin Linden who has worked with Bob Dylan, Rhiannon Giddens, Bruce Cockburn, and many others.

Harris is currently based in Chicago, but was actually born in rural Ohio. She took to music at a very young age, inspired by her parents’ record collection. After attending the University of Michigan’s School of Music, Harris moved to Chicago, where she delved into the city’s theater and music scenes. Now, she is about to tour with Taj Mahal and Keb’ Mo’ this summer. BGS had the pleasure of catching up with Anne Harris for a conversation about the new album, her Amanda Ewing-built violin, her influences and inspirations, and more.

To start, tell me where and when I Feel It Once Again was recorded.

Anne Harris: I did the record in Nashville. Coming out of the pandemic, I had been writing and I felt like I had a collection of songs – a pool of things that I wanted to be on my next record. I wanted to work with a producer, [but] I wasn’t sure who to work with. All my prior records had just been basement records, basically. Nothing wrong with that, but I wanted to bring things up a level. A friend of mine, Amy Helm – who is an amazing singer-songwriter in her own right – recommended Colin Linden to me.

Colin is Canadian born and raised. Incredible multi-instrumentalist [and] producer that’s made Nashville his home for many years now. Anyone [Amy] recommends I’m gonna listen to. So I started listening to some of the records he made. I got in touch with Colin and sent him, in really rough form, a big basket of songs I was considering. He really loved them and wanted to work on the record. We got the basic core of the record laid down in about a week of intense recording in Nashville and finished up with a few things remotely after that.

Is it true that you first picked up the violin as a kid after watching Fiddler on the Roof?

Yeah! My Mom took my sister and I to see the movie version of Fiddler on the Roof when we were little; I was around three. I was born and raised in Yellow Springs, Ohio. I remember being at this movie theater in Dayton for a matinee. I remember the picture of the screen – you know, this opening scene where Isaac Stern is in silhouette on a rooftop playing the overture. And [my mother] said I stood up, pointed at the screen, and yelled – as loud as I could – “Mommy! That’s what I wanna do!” She was like, “Okay, you gotta sit down and be quiet.”

She thought [it was] maybe a passing thing and that I was caught up in the drama of the music. [But] I just kept bugging her about it. So she let me do a couple of early violin camp kind of things here and there. I just had this intensity about wanting to really study it. So when I turned eight, I started studying privately with a teacher. Suzuki and classical training was sort of my background.

Tell me about the title track, which is also right in the middle of the album. What inspired “I Feel It Once Again?”

A couple of years ago, [my] friend Dave Hererro – who is a Chicago based blues guitar player. Sometimes he’ll come up with a little riff and send it my way and say, “What do you think of this?” He sent me this guitar riff, which is kind of the through line of that song. I heard it and immediately the whole song and story unfolded in my head. I wrote [it] around that guitar riff in, like, one session. I did a demo and I played it for Dave. I’m like, “Dude! I love this so much.” He’s like, “Well, do whatever you want with it!”

Writing is an interesting thing. I’m not super prolific. I’m not one of those people that’s like, “I journal every day for 13 hours!” [Laughs] You know? [I don’t] have a discipline or method other than trying to stay open to inspiration and committing to it when it happens.

[That] was the case with that song. I had the story and a picture in my mind of what that song about. Somebody musing over a loss. You know, it’s twilight and they’re finishing a bottle of wine and mourning the loss of this great love. One part of you is fine when it’s daytime and you can put on a face and you’re going about your business. But then when the curtain comes down, behind that curtain is this loss and this mourning. That’s what that song is about.

Everything looks different at 4am, doesn’t it? [Laughs]

I [also] wanted to ask you about “Snowden’s Jig.” That’s a type of music I know virtually nothing about. I know it’s a traditional.

Yes. “Snowden’s Jig” is a tune that I learned from the Carolina Chocolate Drops record Genuine Negro Jig. It was my gateway into the Carolina Chocolate Drops. I was doing errands somewhere and I had NPR on and [they] were a feature story. And it was just this mind-blowing thing.

Joe Thompson [has] been deceased for a while now. But he was one of the last living fiddlers in the Black string band tradition. They would go to his porch, learn tunes from him, and learn the history of Black string band tradition. That’s sort of how they started their group. [“Snowden’s Jig”] was on that record and they learned it from Joe.

Part of my mission as an artist is to be a bridge of accessibility through my instrument, the violin, to the Black fiddle tradition. There was a time during slavery days when the fiddle and banjo were the predominant instruments among Black players. Guitars were sort of a rarity. That was when string band music was really at its height. North New Orleans was the sort of center of Black fiddle playing. Often time, enslavers would send their enslaved people down to New Orleans to learn how to play fiddle and then come back to the plantation to entertain for white parties and balls.

You’re based in Chicago. It’s a big music city. How has living in Chicago informed your music?

Chicago is known as a workingman’s city, a working class city. There’s something very grounded about Chicago in general and that’s the reputation it has. I’m a Midwestern person [anyway], from Ohio originally. There’s something about us in the Midwest. You know, we’ll never be as cool as New York or LA! But we work our asses off. I feel that translates into the artists in this town. It’s really a place where it’s about the work.

This album apparently marks the first violin commission between two Black women. Yourself and Amanda Ewing?

Correct. Amanda Ewing. It’s the very first professional violin commission that’s been recognized in an official capacity. Amanda has a certificate from the governor of Tennessee – she’s a Nashville resident – citing her as the first Black woman violin luthier in the country.

When I first saw Amanda, it was online. The algorithm basically brought her to my phone. I saw a picture of this beautiful Black woman in a work coat, holding the violin and I about lost my mind. I was so blown away and inspired. I read her story and got in touch with her and told her, “I have to have you make a violin for me. I have to own a violin that was made by the hands of somebody that looks like me.” It never occurred to me, in all my years of playing, what the hands of the maker of my instrument might look like. That’s not an uncommon thing, but it’s sort of sad! It would never occur to me that a Black woman would be an option.

So as soon as I met her, we embarked on a commission that was funded by GoFundMe. She decided she wanted to make two [violins] so that I would have a choice. They were completed in February, a couple of months ago. [One violin] will make its official debut for a public audience on the 23rd of May. I’m gonna be playing at the Grand Ole Opry with Taj Mahal and Keb’ Mo’. I’m going on tour with them.

It’s funny, I was gonna ask you next about that tour! I noticed you had some upcoming tour dates with Taj and Keb’. I wanted to ask your thoughts on that and maybe what people can look forward to on this tour.

A friend of mine is Taj Mahal’s manager and she’s also good friends with Keb’. She said that Kevin [Keb’] had approached her looking for a violinist player for this upcoming tour. They have a new record out as TajMo called Room On The Porch. It’s their second under that moniker and it’s an amazing collaboration. Two iconic figures making beautiful music together. So she recommended me and [Keb’] had seen me before – I think when I was touring with Otis Taylor years ago. He called me and you know I’ll keep that voicemail forever!

As far as what to look forward to, it’s gonna be amazing. The opportunity to work with luminaries… I’m gonna be the biggest sponge, soaking up all of the knowledge from these giants. Taj has been influential to just about everyone on some level. He’s one of those people who’s worked with everybody and done so much. I’m just over the moon.

Photo Credit: Roman Sobus