I first heard Doc Watson’s music when I was a child, as Doc was a featured artist on the first album I ever listened to from beginning to end, the 1964 Elektra/Folkways 4-LP compilation set The Folk Box. From that initial exposure to Doc’s fluid acoustic guitar playing and resonant singing I acquired a few of his 1960s albums on the Vanguard label. I became a fan, and like many others I witnessed Doc’s legend expand in the wake of his participation in the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s popular 1972 album Will the Circle Be Unbroken. Throughout the 1970s Doc toured constantly, and he recorded frequently, but his music didn’t significantly change, as he continued to explore his distinctive “Traditional Plus” repertoire into the 1980s and beyond. On several occasions I heard him perform in concert alongside his son Merle, a formidable guitar player in his own right, and bassist T. Michael Coleman.

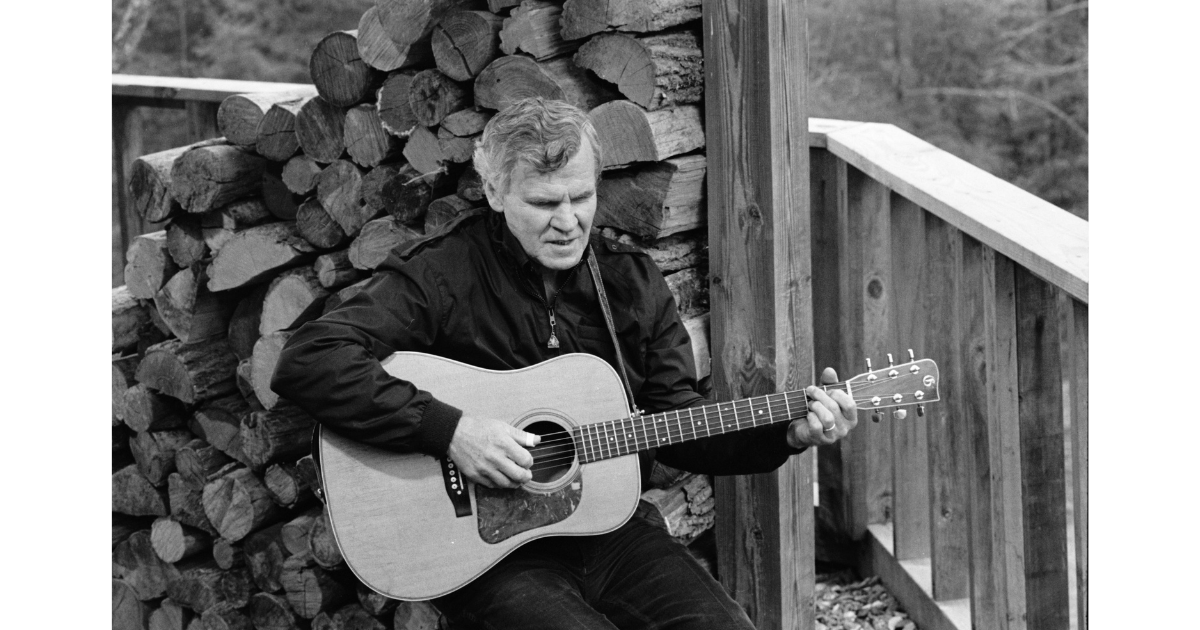

In 1984 my work for the National Park Service brought me to the same mountainous North Carolina county in which Doc lived, in the high Blue Ridge not far from the Tennessee-North Carolina boundary. My landlord, who learned of my interest in Doc’s music and who knew the Watson family, offered to arrange for me to meet Doc. While I never pursued such a meeting, I continued to seek out every opportunity to hear Doc’s music. Some years later I moved to Johnson City, a valley community in East Tennessee, and learned that Doc had been a key member of a Johnson City-based country band during the 1950s, long before he achieved national recognition. It was comforting to still be living in “Doc country.”

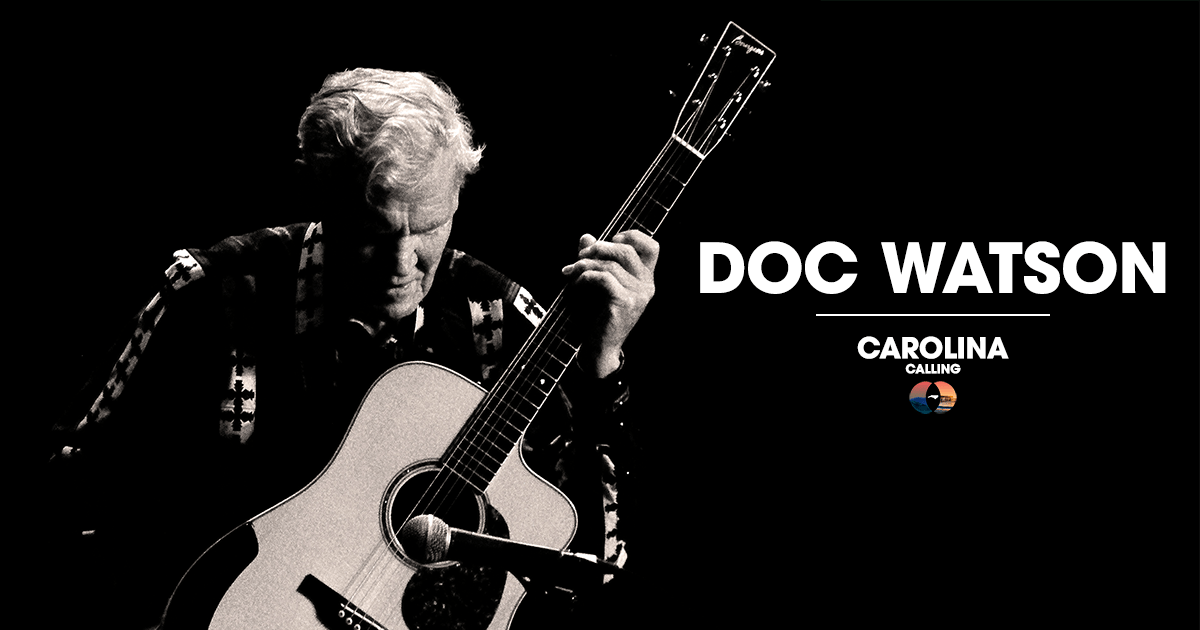

In my position at East Tennessee State University I researched Appalachia’s music history and taught Appalachian Studies, and everyone I met (young and old, local and from elsewhere) always agreed that Doc was special—that he was one of America’s greatest folk artists yet in his everyday demeanor “just one of the people.” For much of his long career through his death in 2012 Doc was Appalachia’s unofficial cultural ambassador who brought people together in rapt attention to his singular musical gifts, of course, but also in shared appreciation of the roots music heritage that Doc simultaneously preserved and transformed. And his gifts and his impact will live on in the recordings he made and in individual and collective memories of this humble and inspiring master musician.

For me, then, it has been the honor of a lifetime to co-produce (with Scott Billington and Mason Williams) and to contribute liner notes for Craft Recordings’ new box set Doc Watson: Life’s Work, A Retrospective. Containing 101 key recordings by Doc over 4 CDs and featuring an 88-page book with extensive notes and rare photographs, Life’s Work celebrates the legacy of this master musician. The first comprehensive overview of Doc’s life and recording career, the set is intended equally for longtime fans of his music and for those unfamiliar with him. The following ten recordings from Life’s Work are examples of Doc’s “Traditional Plus” repertoire, and it is hoped that these examples will help illustrate why he is widely considered as among the most important figures in the history of American roots music.

“Storms Are on the Ocean” (Jean Ritchie & Doc Watson)

In 1963 Ralph Rinzler coordinated a double-bill at Gerde’s Folk City in Greenwich Village featuring established folk star Jean Ritchie and newcomer to the urban folk music revival circuit Doc Watson, who performed a set together. Fortunately for posterity, Ritchie’s husband George Pickow recorded the proceedings, and that same year Folkways Records released the album Jean Ritchie and Doc Watson at Folk City. One performance recorded during the Folk City set–of The Carter Family’s early country classic “Storms Are on the Ocean,” originally recorded at the 1927 Bristol Sessions and based on a traditional Scottish ballad–captured the wistful sweetness in A.P. Carter’s lyrics and also demonstrated Doc’s gifts at duet singing.

“And Am I Born to Die”

This Methodist hymn, composed by 18th Century English minister Charles Wesley, was included in The Sacred Harp (1844) converted into a shape-note arrangement entitled “Idumea.” (The soundtrack for the 2003 film Cold Mountain featured the angular minor-key harmonies from a shape-note performance of “Idumea” to set the mood for a key scene.) Acknowledging that he first heard “And Am I Born to Die” when he was a 2-year-old sitting on his mother’s lap at Mount Paran Baptist Church near his home in Deep Gap, North Carolina, Doc related that his a cappella hymn-singing style was strongly influenced by that of his grandfather Smith Watson. This recording, among some 1964 field recordings made of Doc and his family in Deep Gap by Rinzler and Daniel Seeger, was finally released (with other recorded performances from various members of the Watson family) on the 1977 album Tradition.

“That Was the Last Thing on My Mind”

Throughout his long career, Doc performed and recorded a repertoire he himself referred to as “Traditional Plus.” This repertoire incorporated material from many genres and sources: traditional music, of course, but also songs composed by early country recording artists as well as by contemporary songwriters. One of the latter songs recorded by Doc, “The Last Thing on My Mind,” was written and first recorded in 1964 by Tom Paxton. The next year, Peter, Paul and Mary and The Kingston Trio covered the song, but those versions pale in comparison to Doc’s 1966 rendition, featured on his Vanguard album Southbound. Doc would record the song again and frequently perform it live, including at Merlefest (where in 2001 he performed the song in a duet with another fan of Paxton’s song, Dolly Parton). Doc remained a fan of Tom Paxton, recording several Paxton songs over the years.

“Alberta”

Frequently recording affectionate interpretations of blues compositions, Doc was a fan of several genres of Black music. Originally a steamboat work song sung by Black roustabouts, “Alberta” was performed over the years by many musicians associated with the urban folk music revival, from Lead Belly and Burl Ives to Odetta and Bob Gibson. Doc developed his rendition of “Alberta” not from those examples but from a version on the 1963 RCA Victor LP Come All Ye Fair and Tender Ladies, which featured folk revival-era songs crooned by Bonanza actor Pernell Roberts.

“Matty Groves”

“Matty Groves”—from Doc’s 1967 album for Vanguard Home Again!—was the musician’s rendition of a 17th century ballad chronicling an adulterous relationship between an aristocratic woman and a commoner man; the woman’s husband, who was a Lord, discovers the tryst and kills both his wife and her lover. Doc performs this grisly ballad with an expressive yet restrained voice, revealing his familiarity with traditional balladry. This performance, clocking in at 6:07, underscores his keen memory (so many verses!) and his flawless sense of timing (his guitar accompaniment was understated and delicate yet propulsive).

“Nothing to It” (Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs with Doc Watson)

Doc first recorded this instrumental (credited to him but probably influenced by the old-time song “I Don’t Love Nobody”) as a solo piece for his 1966 Southbound album. Impressed by Doc’s dexterity on the guitar, the sound engineer asked the guitarist “What the heck was that?” Doc answered, “Aw, nothing to it.” The title was ironic because the tune was indeed quite challenging. The next year Doc brought the tune to sessions for Flatt & Scruggs’ next album, invited to participate by Earl Scruggs, who was in awe of Doc’s virtuosity on the guitar. This bluegrass-band version of the tune was released by the Columbia label on the 1967 Strictly Instrumental album. Doc, in turn, was fascinated by Scruggs’ banjo style, and the two North Carolinians would perform together on stages and for records throughout their long careers.

“Deep River Blues”

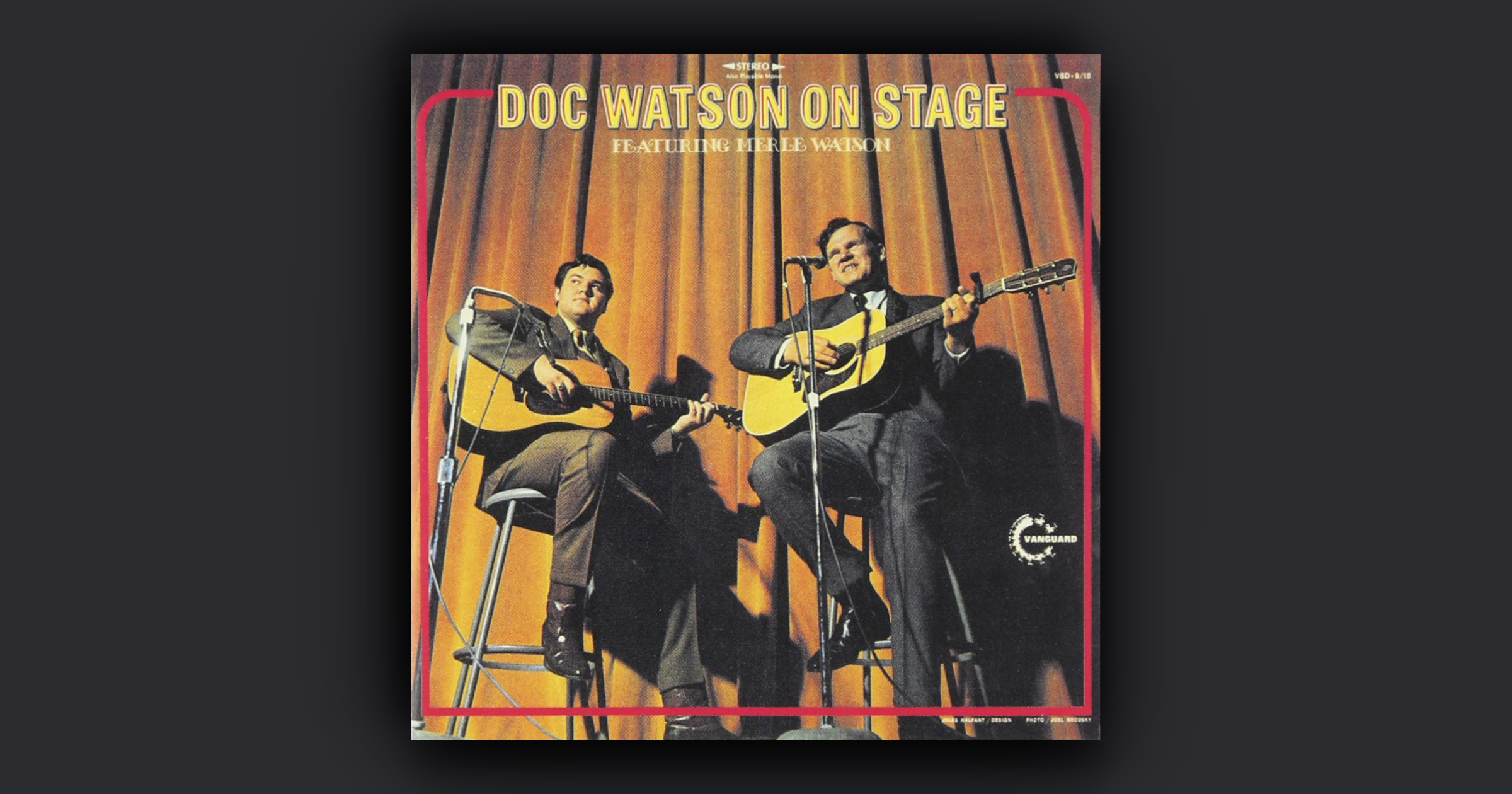

First recorded by The Delmore Brothers in 1933 with its original title “I’ve Got the Big River Blues,” “Deep River Blues” was one of Doc’s most requested songs, and he clearly enjoyed performing it. Yearning to play this song on his guitar occasioned one of Doc’s most important stylistic breakthroughs on the instrument: he learned how to incorporate aspects of Merle Travis’s finger-style technique (known as “Travis picking”) into his own style. As Doc himself said of “Deep River Blues” in notes included in the 1971 book The Songs of Doc Watson: “This blues was introduced to me in the late thirties by a Delmore Brothers recording. … I never could figure a way to get even a resemblance of the sound that they got until I began to hear Merle Travis pick the guitar. When Merle plays the guitar, he gets a rhythmic beat going by bouncing his thumb back and forth on the bass strings, which he mutes with the edge of the palm of his hand. I worked out that little back-up part first, but it took me about ten years before I got the whole thing sounding the way I wanted it.” Doc recorded this song on several occasions, with a particularly fine rendition captured during a 1970 concert and issued on his live album for Vanguard, On Stage.

“Tennessee Stud” (with Nitty Gritty Dirt Band)

As Doc says in the spoken introduction to this legendary recording, “Jimmy Driftwood wrote this thing.” “This thing” is the song that would inspire one of Doc’s definitive performances—one that reached the broadest imaginable audience by becoming a favorite among roots music DJs and also among an ever-expanding circle of music fans who discovered The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s influential 1972 album for the United Artists label, Will the Circle Be Unbroken. “Jimmy Driftwood” was the pen name for James Corbett Morris, an Arkansas native who composed such hit “historical” songs as “The Battle of New Orleans.” Driftwood’s song “Tennessee Stud,” lyrically inspired by his wife’s grandfather’s horse, was composed in 1958 and was recorded the next year by Eddy Arnold, one of Doc’s favorite country singers. Other country artists would record the song—Chet Atkins, Jerry Reed, Johnny Cash, and Hank Williams Jr.—and Doc himself first recorded it for his 1966 album Southbound. But Doc’s version backed by The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, recorded in August 1971, quickly took the reins as the definitive version of the song.

“Summertime”

Many musicians might shy away from covering “Summertime,” among the most frequently recorded songs since it was composed by George and Ira Gershwin/DuBose Heyward for the opera Porgy and Bess (1935). But not Doc. No song or tune was too familiar for him, as he could make any piece he performed his own. Other musicians had bigger hits with “Summertime”—Billie Holiday’s version rose to #12 hit in 1936, while Billy Stewart’s peaked at #10 in the Billboard Hot 100 in 1966—but surely Doc’s version of “Summertime,” appearing on his album Elementary Doctor Watson (released in 1972 on the Poppy label), is among the greatest recorded performances of this classic from the American songbook.

“Corrina Corrina” (Doc & Merle Watson)

First documented in a 1918 sheet music arrangement entitled “Has Anyone Seen My Corrine?” and recorded later that same year by Vernon Dalhart for the Edison label, this traditional blues chestnut (sometimes called “Corrine, Corrina”) has been championed over the years by countless musicians—by blues musicians like Blind Lemon Jefferson (1930), by “Hillbilly” musicians like Clayton McMichen (1929), by pop and rock covers by Bill Haley & His Comets (1955), Ray Peterson (a #9 pop hit in 1960), and Bob Dylan (1962). Similarly, musicians working in such niche genres as Western swing and Cajun have included “Corrina, Corrina” in their repertoires. Doc and his son Merle Watson recorded their version for their 1973 Grammy Award-winning album Then and Now.

About Ted Olson

Ted Olson, Professor of Appalachian Studies at East Tennessee State University, is the author of many articles, essays, encyclopedia entries, poems, and reviews published in a range of books and periodicals. He has produced many documentary albums of Appalachian music, and for his work as a music historian he has received an International Bluegrass Music Association Award; three Independent Music Awards; the Ramsey Award for Lifetime Achievement from the East Tennessee Historical Society; and seven Grammy Award nominations. Olson is presently serving as co-host (with Dr. William Turner) of the podcast Sepia Tones: Exploring Black Appalachian Music.

Photo Credit: Hugh Morton Collection (black and white image); Charles Frizzell (color image)