Singer-songwriter and instrumentalist Carl “Buffalo” Nichols loves and treasures the blues, but he acknowledges that his vision of what the music can and should do differs greatly from that of many performers he’s met in the field. Indeed, Nichols, whose brilliant new LP, The Fatalist – his second for Fat Possum, which dropped September 15 – doesn’t mince words when he discusses the issues he faces and the things he wants to see change in regards to the music, as well as attitudes held by many in positions of authority in regards to its promotion and distribution.

“I tell folks I’m a songwriter initially, because when you say you’re a blues musician, then there’s a whole bunch of stereotyped impressions that you’ve got to get beyond,” Nichols said during a lengthy recent phone interview with BGS. “There was a period there a couple of years ago, right after George Floyd, where for a time there was this sense, or at least it was being said, that the blues community needed to change, we needed to diversify, to become more relevant and reflective of things happening in America. But now that seems to have passed, and we’re back to the same old thing. There’s too much conservatism among the older crowd, who often are in control of the blues radio stations and who are responsible for why the music isn’t more widely heard and accepted. And there’s too many artists just putting the same stuff out there.”

Nichols is among a growing number of African American artists anxious to smash idiomatic barriers regarding not just blues, but American music, period. He is a master at carefully paying attention to traditional values like keen storytelling, soulful delivery and expressive lyrics, while also utilizing contemporary elements and devices. The Fatalist includes a stunning cover of Blind Willie Johnson’s majestic “You’re Gonna Need Somebody On Your Bond.” The LP’s first single, Nichols’ robust baritone soars through the message of salvation with vigor, driving home both its urgent intensity and evocative theme. However, Nichols also says the song epitomizes another part of the dilemma he faces regarding broadening the blues’ appeal.

“That one kind of gets caught in a double trap,” Nichols continued. “On the one hand, you’ve got religious lyrics, then on the other you’ve got the blues sensibility. So, while the traditionalists who know Blind Willie Johnson love it, it has a hard time getting past the gatekeepers, because it also has some contemporary production touches. That’s kind of the double struggle you face. You’ve got the white traditionalist and conservative types who are dominating the blues marketplace, then when you’re trying to reach the Black audience, you’ve got what they call the ‘urban contemporary market.’ Because it’s blues they won’t play it.”

Still, Nichols is making some headway on the scene, both critically and in terms of gaining followers. He says he’s seeing a lot more young folks in his audience, as well as more Black fans. Though his appeal and notoriety don’t yet match that of a Christone “Kingfish” Ingram or a Shemekia Copeland, Nichols is steadily gaining more attention and acclaim. He opened several dates last year for Valerie June, another marvelous Black performer whose music incorporates classic and current sounds. He stands prominently alongside other rising blues stars like Gary Clark Jr., Marquise Knox and Eric Gales. The Fatalist reflects the vision and scope of a 30-something performer whose background includes at various times being in a grindcore band (Concrete Horizon), and playing folk and Americana, while also being part of a duo in Milwaukee (Nickel & Rose) with bassist Johanna Rose. His disenchantment with an Americana scene he considered overwhelmingly white and less than encouraging to his artistic vision led him to Fat Possum.

“I really felt it was important at this stage to have a label behind me,” Nichols said in response to a question about why he chose to sign with Fat Possum. “While it’s not the type of thing where we’re sitting down and trying to pick songs for radio, it is a thing where they’ve been very supportive and encouraging. They’ve provided me a place and a forum for what I want to do, and they appreciate my vision and are doing all they can to help me.”

The Mississippi-based label was once widely celebrated for its championing of hill country blues greats R.L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough, but in recent years had drifted far away from that model. Buffalo Nichols, his debut release, was the company’s first blues outing in two decades. It set the stage for The Fatalist, whose eight songs reveal a strong songwriting focus Nichols says is indicative of both personal growth and his desire to use the blues form to do more than rip through scales and display great individual musicianship. “I’ve been a guitarist for 20 years, but it’s really only been the last 10 that I think I’ve really grown as a songwriter,” he continued. “Being able to express myself is a challenge, and using the blues to do it is what drives me.”

There’s no question that The Fatalist doesn’t necessarily adhere to the standard blues formula, and that’s setting aside the presence of drum machine tracks and enhanced sonic quality. Its song sequencing and overall lyrical flow are edgy and compelling.

Standout cuts like “Love Is All” or “The Difference” offer contrasting views of a relationship. The former is optimism grounded in the wisdom of admitting that even good guys can go astray, while the latter spotlights a breakup that doesn’t so much place blame as document the painful end of something that was once glorious. There’s also the hard-hitting opening number “Cold Black Stare,” and the triumphant finale, “This Moment,” that features special guest vocalist Samantha Rose. The album has a sonic clarity and power that puts it in a league with anything done at a state-of-the-art studio in Nashville, LA, or New York, yet it was recorded in Nichols’ home – and he produced it. The decision to cut it there is also part of a larger career change that Nichols made last year, when he moved back to Milwaukee after spending years in Austin.

“In some ways it’s harder for me now being back home,” Nichols said. “But in other ways it’s good, because now I have to do it myself. I don’t have the machinery or the apparatus or the surroundings that I would have in Nashville or Austin or LA. It’s like it was when I was growing up. I’m being responsible for my own music now, and that’s a good thing creatively, even if from a business aspect sometimes there’s a struggle.”

Buffalo Nichols is now in the midst of an extensive tour, with the American portion running through mid-December, then a European leg beginning in early January and continuing through mid-February (for now). While being adamant about not setting goals, Nichols says he definitely has things he wants to accomplish career-wise.

“For me, I always want to look ahead, I want to progress as a songwriter and a guitarist,” Nichols concluded. “I don’t ever want to make the same music over and over. I don’t want to be predictable. I want to contribute something original, something that when I’m gone people will look back and say that this was something fresh and inventive that Buffalo Nichols made.”

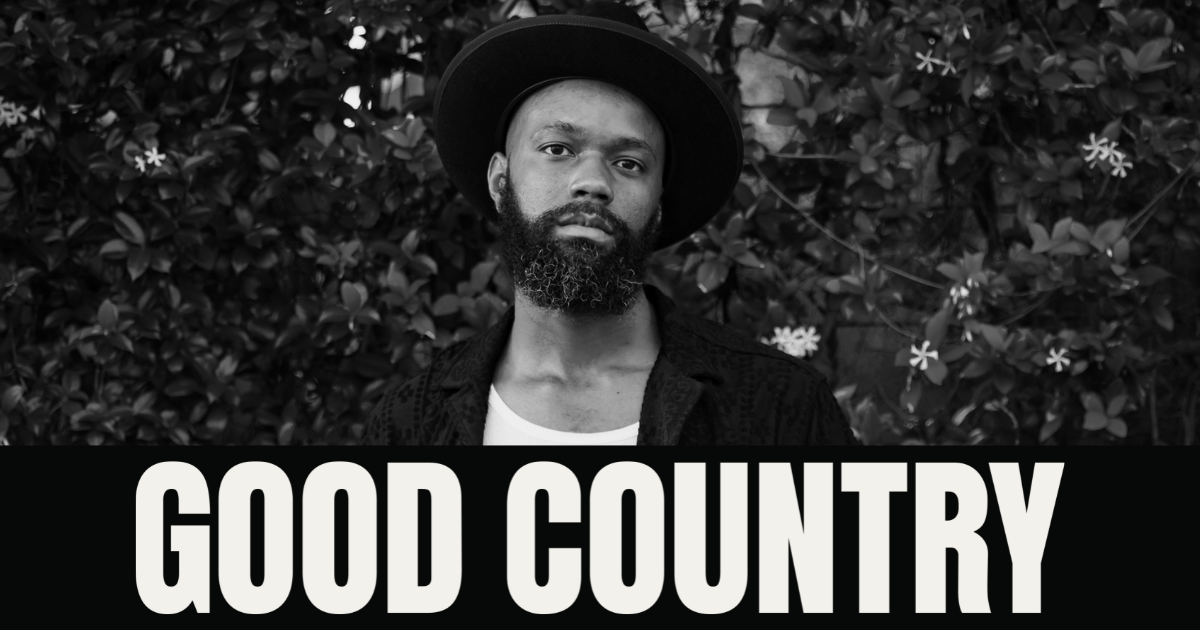

Photo Credit: Samer Ghani